He had one treasure: a small, slim book with a maroon cover, its pages begun but never finished. He found it in the gutter one summer morning, its cover damp and smelling faintly of riverweed. The pages were filled with neat, adult handwriting: fragments of letters, a list of names, a pressed flower. Somebody had lost something of themselves inside it. The boy kept the book pressed to his chest like a talisman. He learned to read at night with the borrowed light of a baker’s candle, fingers tracing the letters like a map to an impossible place. Words became a thing he could eat with his eyes; sentences like warm broth. He read of things he had never seen: palaces that smelled of polished wood, seas that were not rivers, trees that bowed with the weight of birds rather than coal. He learned the rhythm of language and the way a single paragraph could make him bigger than his coat.

The book also carried, inexplicably, the idea that other people could be changed. The boy began to believe — not in miracles, perhaps, but in the mundane operations of possibility — that sometimes a life could tilt toward light because someone else’s hand pushed it. He kept that belief as one keeps a half-mended hope: fragile, but workable.

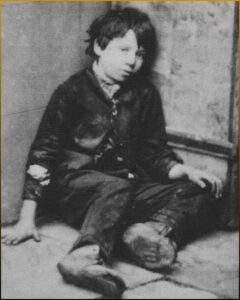

Winter came the year he was eleven as if the city had decided to punish itself. It arrived early, like a strict teacher, with a wind that cut and a snow that made the alleys unfamiliar. The Thames exhaled lazy white smoke. The poor clustered tighter, their laughter brittle as ice. Food shrank in the markets and the carriages grew thicker with furs because the wealthy could afford to buy warmth. The boy’s coat was a single layer too thin; his boots had holes big enough for cold to plant itself in his toes.

On a night when the moon was a slender coin, a new danger arrived: fire. Fires in London were seldom dramatic in the way of novels; they began as sparks, as careless embers that licked a curtain or startled a chimney. This one began in a row of backhouses, where a family had stacked coal too close to the brazier. A gust pushed smoke along a lane that smelled of stew and wet straw. The night was full of coughing; the children alerted to the unfamiliar roar that grows into animal panic. The boy woke because someone had kicked his bundle; he saw a glow and then the world rearranged itself into two colors: the dull black of the alley and the orange of a hungry thing.

They ran. The children assembled like a flock on the move, feet slapping, breath frosting the air. The boy could not tell whether the flames were frightening because they promised burning or because they were bright enough to be seen by the ones whose faces usually looked away. In the chaos, he saw a girl not in their group, a small child with a braid undone and eyes like flint. She had been part of the market-basket circle that shared pies and scolded one another gently; she was the sort who smiled at insects and gave them names. She had been playing near the backhouses.

The boy did not think; he ran. The fire made everyone clever, clear. People who had been strangers became linked by their fear. The boy threw his shoulder into a wooden fence and vaulted into the yard, lungs filled with smoke. He found the girl huddled among crates, coughing and clutching a doll whose face had been painted by a sleep-noise hand. Her name was Elsie; the boy, who had no name to offer, mechanically seized her hand because it was there. Their feet found one another. They burst through the crowd and spilled into the street, where a gentleman in a greatcoat — wide enough to wrap entire secrets in — pulled them away from the heat and into another light: the rescue-light that gives a child a name in the mouths of adults.

That night changed the boy’s life in the way sharp instruments change a painting: not by erasing it but by exposing layers beneath. The fire dismantled a row of backhouses, and in its ruins the city revealed its skeleton: landlords and tenants, certificates and debts, the clause-laced legal language that justified hardship. Men with clipboards arrived in the daylight and a cluster of people in beaver hats — men who looked like they wrote charity into statutes — fanned out with sympathies. The boy watched them from a distance, because he had been taught the prudence of watching. They made lists of names, of which the boy was not included; he was a “child of the streets,” and someone of the streets did not go on a list unless someone in boots noticed them twice.

Yet, there were exceptions. One person noticed him. She was neither the sweep nor the clerk nor the wide-hatted gentleman; she was a woman wrapped in a plain coat, with a shawl around her shoulders that looked as if it had been turned into armor against compassion. Her hair had been braided and pinned as if to keep it from looking too urgent. She moved differently from the other rescuers — not the haste of paperwork, not the theatrical sympathy that made a show of soot. She surveyed the children with eyes that skimmed and stayed. When she looked at the boy, she did not look at his coat; she looked at the book pressed under his arm, its maroon cover smudged but still red enough to mean something.

“You have a book,” she said, and her voice was the kind that resembled a door opening. It carried no pity and no accusation. Only note-taking curiosity.

The boy clutched the book as if it were the only solid thing in a world that had turned fluid. He could have lied; he had lied for bread. He could have said it belonged to someone else. But the woman’s gaze did not invite deception. He shrugged, and the book slipped out of the bundle and into her hands before he could stop it.

She opened it and read a few lines under her breath, not with the hunger of someone who needed to learn to read but with the gentleness of a person who understood language as a tool for tending. When she looked up, she smelled faintly of herbal tea and dusted papers. “My name is Agnes Marlowe,” she said. “I run a small reading circle. We take in stray papers and mend them.”

The boy knew the word “mend.” The word had come from a tailor who once let him sleep behind his shop and taught him to thread a needle with the impatient authority of a man who had fixed his own future once and knew the exact cost. “I don’t belong to anywhere,” the boy said.

“Everyone belongs to something,” Agnes said. “Even if it’s a book.” She handed the maroon volume back. “This one should have a proper home.”

She did not take him that night; the world was still busy burning and rearranging. But she did something that few else had done: she watched. She found him the next day, not with a policeman’s sternness but with the slow persistence of a person who persisted. He sat on the kerb near the rebuilt fence, the soot already settling back on his eyelashes. He was small in the geometry of that lane, a shorthand for a life truncated.

“Come,” she said. “Just this once. Come have tea.”

It was not a grand invitation. The Marlowe rooms were a narrow, book-crammed apartment above a shop that sold secondhand globes and used ink wells. It smelled like paper and lemon peels, like the kind of cleanliness that came from ordering things rather than from wealth. The floorboards had a memory of many feet. Her table had five chairs and a cupboard stuffed with tins of tea that someone had labeled in careful pen strokes. She gave him a cup in a bowl and a sliver of bread, and while he ate she told him stories like she was threading the room with rope: small stories of people who found other people, of lost letters returned, of the way paper could press silence into song. He listened because listening is one of the most honest trades of the poor; he traded his silence for her words.

Agnes did not pretend she could fix everything. She laughed at superstitions and was blunt about the limits of charity. She also had a stubbornness like a keel beneath a small boat; she believed in the steady application of small mercies. She arranged for the boy to sleep on a pallet in the attic, where the cold was less immediate and the roof did not leak as much. She supplied him with a blanket that had been unpicked and rewoven at the seams. She insisted he wash, which he did not like but secretly appreciated; water had a way of rearranging the world, making it more survivable.

Yet Agnes did something more dangerous than feeding him or giving him blankets: she taught him to read with intent. She did not push him into the town’s schools, where children of his sort were often fields for moralizing. Instead she put him with the reading circle, a small congregation of people who worked with letters and pressed them into new meaning. They were not all saints; some were fallen professionals, some were women who had given up marriages for quiet work, some were ex-clerks who had a patience with grammar and an impatience with some of the city’s cruelties. They read aloud, and they listened. They argued about sentences. They showed him maps of places he had only seen in mist.

He absorbed the book as if it were food. Words became more than instructions; they were a kind of architecture he could step into, an interior that he could own. He learned of writers who had invented worlds and people who had no names but became memorable because somebody had written them down. The reading circle gave him a name — not a legal one, but one that enough people used that it pressed into existence. They called him Jonah, because he had once sat under a bridge like a prophet swallowed by the city. Jonah liked the name. It fit like a warm patch on a cold coat.

For a while, it seemed as if the city might relent. He grew in small increments. He learned to write his letters with Agnes’ patience guiding his wrist. He sold newspapers in the morning and studied in the afternoon. He worked in the evenings in the Marlowe rooms, sweeping, carrying coal, helping Agnes fold the pamphlets she used to teach local workers to read. He saw a pattern in kindness — not a single thunderbolt but a slow, patient rainfall. Agnes did not adopt him in a dramatic, romantic sense. She provided him corridors: introductions to people who could give small jobs, introductions to other boys who were trying to leave the streets. She helped him to get a very small legal paper with his name written on it. He held it like a passport to a different identity.

Beyond Agnes, other forces were at work. The city’s civic heart pulsed with debate about “the child question.” Men in offices argued about reform, and pamphlets bloomed like weeds about the need to change the system that let children be children for the wrong reasons. Parliament had a way of sounding like a separate country; its laws slithered slowly into the streets. There were houses of refuge and industrial schools, institutions whose names sounded loving and sometimes were loving, sometimes hungry. The reading circle argued about these things over tea and paper. Agnes was pragmatic where they were idealistic. She said that institutions could sometimes offer a ladder, but often they were cages gilded with good intentions. Jonah learned to listen to both sides.

He also began to see the city with a sharper eye, noticing the fissures where a person might slip. He learned where coal was cheap, where a household left a spoon on the stoop. He also learned the uglier things: the magistrates who dressed pity as punishment, the men who smiled with sharp teeth and handed children into worse hands. His innocence dimmed. Yet, within this more complicated map, the children of the streets were no longer merely prey but also agents. They took work, they bartered favors, and they sometimes took bold chances.

One such chance nearly cost him everything. A drayman asked Jonah whether he wanted to ride along in the wagon for a small fee. The work was hard but legal; he would lift crates and carry sacks. Agnes advised caution, but money spoke louder than caution. Jonah took the job about a month before his twelfth winter. For three weeks, he delivered bundles to markets, and his pocket grew a little heavier. He bought a pair of boots without holes, soldy on a Tuesday morning to a shoemaker who had a hangover and a soft heart. The boots fit like an apology from the city itself.

Then one afternoon, the wagon was hired to carry casks across a narrow bridge. Jonah helped to steady a load when a wheel hit a fissure and the cart lurched. The cask swung, and one of the drivers — a man with knuckles like iron — swore and shoved. The cask rolled. In the scramble a crate fell open and out tumbled a bundle of letters, tied with a ribbon. They were urgent-looking: the kind with blue stamps and addresses written in neat hand. Jonah gathered them because he had a compulsion to gather beauty when it fell into the gutter. He shoved them under his shirt, intending to return them. A voice barked; the drayman accused him of pocketing them. Jonah, who had learned to be small, did not protest much. He could have explained, but explanations hold less weight than fists. The man hit him. In the moment of pain Jonah made a choice: whether to fight and risk being taken to court, or to run and risk being forever mistrusted.

He ran. He ran across the bridge with the letters in his folded palms, the city a blur of faces and steam. The drayman chased him with the rage of someone whose labor had been slighted. They collided with a woman whose umbrella came down like a question mark. The letters flew. A child will learn how to lose all his life; he will also learn to pick up what falls and claim it as his own. Jonah picked up the letters and kept them.

He carried them to Agnes, because habit made the decision before fear could. Agnes read them and set the stack on the table like a stack of live birds. They were not ordinary letters; they were for a man who ran a printing press, a man named Elias Thorn. Somewhere between the wheel and the bridge and the drayman’s curse, a window had opened into a room where the city’s voices were printed. Elias Thorn was a man of contradictions: a printer who sometimes printed subversive pamphlets that made the police nervous, a man with a generous laugh and a temper like a bell. He had been in the reading circle before illness and had remained a figure on the periphery.

Agnes insisted Jonah return them. Jonah, who owed Agnes more than he could count, agreed because the moral arithmetic of being in debt is a weight that makes you honest or crazy. He walked to the printing shop on a damp morning with the letters in his pocket and the boots he had bought worrying the cobblestones. Elias Thorn’s shop was a press-lined cavern, smelling of ink and apple cores. The machine was a beast whose teeth printed words in even rows.

Elias took the letters from Jonah with a suspicion that was almost regretful. He read them and smiled, a quick, small smile. “You did the right thing,” he said. And in his hands Jonah felt the difference between suspicion and warmth.

This small act of returning the letters did not redeem Jonah before the world, but it opened a door. Elias had an eye for hands that could be taught. He offered Jonah a job in the press: odd jobs at first — carrying paper, inking rollers, learning the crude alphabet of type — but an apprenticeship by inclination if not by contract. Jonah accepted. The press became another kind of school. The noise of the machine settled into a rhythm that fit him; the smell of ink was a substance that announced permanence. He learned the names of fonts and the neat geometry of printed lines. He found that arranging letterforms had the same satisfaction as arranging a stolen apple on a tray: it turned nothing into something, gossip into permanence.

It also brought him danger. The press was a hub of ideas, and printers often printed what the paper-writers would not. They printed pamphlets for suffragists, for workers, for men and women who believed the city could be persuaded to be kinder. The authorities sometimes cracked down on such voices, and the press became an editor’s battlefield. Jonah learned to move through this with the kind of care taught by necessity. He learned that his smallness could become an advantage: not a thief but someone who could be invisible when danger arrived.

Years flowed in the press’s steady click. Jonah grew not only taller but deeper. Work made his hands honest. The boots that had once been thin now fit like an adult’s. He began to understand how to make a paragraph hold weight. He learned also to keep secrets: which words would burn the wrong paper and which ones could be set down quietly. He made friends there: Elias, who taught him the press’s manners; Sylvia, a typesetter who had a voice like a bell and a laugh like spilled silver; and Margaret, a deliverywoman who could read faster than any man he knew. With them, he started to imagine that one day he might be more than a child of the gutters.

But the city is not a linear story that resolves happily because a boy learns to set type. In the summer that Jonah turned sixteen, the press published an editorial that made the magistrates’ moustaches bristle. It condemned the treatment of children in factories and the gauntness of workhouses. The piece was sharp and eloquent, and though anonymous, the magistrates believed it to be the product of some malign mind. The police trailed the press and wagged fingers behind other fingers. A raid occurred at two in the morning when the city was at its slowest, the press’s machines rattling like beasts.

They seized manuscripts and type. The policemen argued loudly as they confiscated Gutenberg-made treasures. Jonah was woken by a hand on his shoulder. He dressed quickly. The room smelled like a dream that had been interrupted. They questioned Elias. They questioned Sylvia and Margaret. They asked about Jonah’s presence in the shop. Jonah told them the truth: he was a press worker. He did not know anything about the editorial’s author. The police did not like truth; they liked confessions. Jonah felt the press of boots and suspicion. A young man who had no family was always under examination; the weight of a name or its lack is the difference between a suspect and a citizen.

The raid ended without arrests that night, but the press’s warmth cooled. Manuscripts disappeared into trunks. Elias grew guarded and quiet. The machine’s rhythm changed, and with it the rhythm of Jonah’s life. Their work became clandestine; the press printed pamphlets in the dead of night, hiding type as if letters were contraband. Jonah found himself in the middle of the printing’s ethical swirl: to speak risked exposure; to remain silent felt like complicity.

During those months a new figure entered Jonah’s orbit: a woman named Dr. Clara Pembroke, who worked in a hospital that treated the city’s poor. She came to the reading circle with an impassioned friend and an armful of grim statistics, and she spoke with a surgeon’s directness. She was not a woman of ornamental sympathy; she measured suffering, and she had a plan that mixed medicine with policy. She asked the reading circle to help publish medical reports that would expose the link between poverty and disease.

Jonah found he admired Clara for the way she operated: clear, relentless, refusing to be romantic about suffering. She also had a compassion that was steady like a wheel turning with purpose. She fathered no illusions about changing the entire city, but she intended to carve out a place where lives could be saved. Jonah began to see in her an instrument of the book’s promise: the word held power to change hands.

He worked with her and the press to create a pamphlet that detailed the conditions of children in the workhouses and factories. It contained interviews and records and a language designed to burn the public conscience awake. Printing it was an act of defiance and an act of rescue. When the pamphlet came out, public opinion stirred in a way that felt like a breeze turning into movement. People who had never had to choose bought papers and read the accounts and felt their stomachs twist. The pamphlet did not revolutionize London overnight, but it made some magistrates uncomfortable and it moved a few hearts.

For Jonah, the success was double-edged. The pamphlet’s voice was the voice of many — and for that the press would be praised and cudgeled. The authorities increased their surveillance. The children of the streets were watched more closely. The draymen carried more suspicion, the policemen looked harder for homeless boys who might be agitators. Jonah’s past — the nights under bridges, the years of survival — became danger because it marked him as someone who could be used, persuaded, or punished. The city can turn an act of conscience into a badge of suspicion, and Jonah felt that pressure like fog.

Then, in the late autumn when leaves were brown as old money, Agnes fell ill. Her cough sounded like a bell in the reading rooms; she refused to be dramatic, but she wasted like a candle. The doctor said consumption — that elegant name for the slow thief that took breath. Clara came often, and the reading circle shifted into a new role: tending to Agnes’ body and to the paperwork that might keep her afloat. Agnes, practical to the end, insisted less on pity and more on orders for her affairs. She made Jonah promise to keep the book going, to keep the reading circle a place for the city’s wandering minds.

Agnes’ death was small and absolute. She died on a night when the rain kept its voice to itself. Jonah sat by the bed and read to her while she listened like someone receiving the last page of a good book. When she was gone, the world seemed to hollow. The reading circle scattered like coins. Elias wrote a letter that he left folded in a pocket; he asked Jonah to consider taking more responsibility at the press. Clara offered him a job delivering pamphlets to hospitals, and a small stipend. He had options, but because life is cunning, the city soon demanded a heroism he had not planned on. It came wrapped in the kind of cruelty that leaves fingerprints only later.

A factory near the docks had collapsed its roof. The collapse was the work of shoddy materials, of corners cut by men who measured profit against safety and decided profit should win. The factory had housed dozens: women, children, old men. The newspapers splashed the scene with images of tragedy. The authorities called for inquiries and played at seriousness. The workers, those who survived, were furious because grief and rage sit close. The Marlowe reading circle printed a pamphlet about the factory’s conditions; Clara used medical evidence as an arrow. The city was uneasy.

One cold afternoon, a delegation of factory owners and magistrates came to Elias Thorn’s shop. Their faces were smooth and apologetic in the way the privileged are when they must pretend remorse. They wanted to make a “demonstration of goodwill.” They offered money to the families. They praised the press’s civility. Jonah saw them in the shop and felt the same old gulf widen, an invisible but palpable river. He also saw something else: a man arriving in the crowd with a look that was almost feral. This man — Thomas Hargreaves — had been a union organizer who wore his conviction like a brand. He came with a band of men and a plan. They wanted to march and to take the factory owners by the collar.

Jonah had always been hesitant to join violent action. The press did not advocate for lynching; it advocated for exposure and public conscience. But that day, when a speaker called the city’s attention to the cost of cheap goods — the children’s bodies crushed under roofs and the fuel of impatient profit — Jonah understood in the marrow why men would choose the harder path. He also saw, in the crowd, a policeman strike a young woman who reminded him of Lena, and that sight made his throat close with a terrible recognition. The protest thundered and grew. Hargreaves shouted about necessity and the right of workers; the magistrates muttered.

At the demonstration, anger tripped into violence. A stone flew and the policeman’s helmet crashed down like a crown losing a jewel. Men in greatcoats shouted for order, and then it happened: a shot, a single gun, and men fell into a scramble that tasted like panic. Panic merges people into shapes; there is no nuance in panic. The authorities suppressed the crowd with disproportionate force. Hargreaves was arrested. The press’s pamphlet was used as evidence of fomenting. Elias and a few others were taken into custody for questioning.

Jonah felt the press of memory: he had never been a stranger to the magistrate’s table. He wanted to speak, to defend the press’s role in truth-telling, but in a city where a child once without a name stood before men who wore names like armor, words sometimes failed. They asked him little but suspected much. They suspected him because he was young and because the state needed a scapegoat. Jonah was not arrested that day, but the shadow of suspicion darkened everyone around Elias. The press’s patrons dwindled, afraid of being associated with seditious ink.

Time sharpened every edge. The press continued in smaller cycles, printing pamphlets quietly, publishing news that was softer but still true. Elias’ health failed. Sylvia found work elsewhere. Jonah delivered pamphlets to hospitals and to a new kind of audience: the workers and the sick and the dominions of people whose faces the courts did not recognize. Clara’s efforts gathered a modest triumph: the magistrates were forced to open an inquiry into factories; wages were debated in committees. The change was incremental, as change must be.

In the background of his outward work, Jonah carried other things: guilt, memory, and the story of a family that never came back. He kept the maroon book on a shelf in the press, a place where papers were kept like seeds. He wrote in it a few times, awkward lines that tried to name things. He wrote about Agnes, about Elias, about the people who had touched him and then been taken away. The book became a ledger of small mercies.

Then, late one winter night, an outbreak of fever — not a polite illness but one that vomits itself through slums — struck near the docks where the press delivered pamphlets. People who had already been weakened by hunger and cold found their bodies failing under a microscopic enemy. The hospital roared with work. Clara rationed her staff; they set up wards in empty warehouses. Jonah found himself delivering not only pamphlets but medicines and messages. He became, in the fragile way that necessity shapes people, an organizer of small surges of assistance.

One night a child arrived at the hospital with a fever so hot her skin shimmered like a thin coin. The child was Elsie — the braid-unraveled girl he had rescued from the fire years earlier. She had been working at a factory when the fever took hold. Jonah recognized her by a scar on her thumb where she had once stuck it into a pastry. She lay under a sheet and did not look like the girl who had laughed at insects. She looked like someone who had been forgotten.

Clara made a bed for Elsie and took a merciless inventory of symptoms. The sickness was voracious. Jonah sat at Elsie’s bedside with a bowl of burnt tea and a bandage clumsily folded. He read to her from the maroon book, words that Agnes had loved, and sometimes she smiled. The fever made her small; it also made Jonah feel like a man whose hands had finally learned how to hold.

The hospital filled with the city’s dying and its caretakers. They worked with shifts like surgeons of patience. The fever ran its course and, by a brittle grace, some survived. Elsie’s breathing steadied like a metronome. She opened her eyes one dawn and said Jonah’s name — not the one he had been given by the city, but the name his friends had called him. He could have wept.

But the fever also took people. Clara caught it, and although she fought like a person with purpose, she waned. Her fever was the kind that not only stole breath but also the glow from a room. The hospital mourned a practical grief: they had to reorganize wards without her leadership. She left Jonah a letter in which she asked him to continue to fight the small fights and not to be satisfied with small mercies. “Change,” she wrote in that letter, “is the careful work of patience and paper. Do not let rhetoric replace remedy.”

Clara’s death was a blow that could have damaged his belief. But instead it became, like Agnes’ death, a hinge on which something new swung into place. Jonah stepped deeper into the press work and into the hospital’s outreach. He developed a way of thinking that combined action with tenderness. He learned that sometimes pamphlets save people by making them angry, that sometimes the angry are saved by medicine. He made a ledger of where the reading circle’s pamphlets were most useful and where beds were lacking. He proposed — timidly at first — a plan to combine the press’s reach with the hospital’s healing: an organized pamphlet drive to inform workers about sanitation and to raise funds for beds. Elias, older and more cautious, agreed to print.

The plan required money and volunteers and a little bit of will. Jonah organized a group of young deliverers and old readers, and he trained them to deliver simple medical instruction in the workers’ dialect. The pamphlets were not grand: wash hands, boil water, recognize fevers. But they were practical, and they were given away with medicine. It was small, perhaps, but within months mortality in certain sectors dropped. The city noticed less and moved on. The point of many reforms is that they are not dramatic; they simply shift the curve.

As Jonah moved in this new orbit, he began to think about permanence in a new way. He thought about the children he had left behind on the streets: Thomas, Lena, Big Ben. He thought about all the times he had been small to survive. He realized that the Marlowe reading circle had been a seedbed for something greater than the sum of its good intentions. The press could be more than a machine for pamphlets; the press could be a conduit for education and a place to train other children.

He proposed a program: teach children to read, to set type, to carry messages. The idea was not revolutionary, but it was hard to fund. Jonah used his influence with Elias’ press and with Clara’s hospital contacts to set up a small apprenticeship scheme. They began with three boys who had been in the hospital and gradually added more. Jonah taught them how to clean type and to set small fonts. Sylvia taught them pace. They paid them with small wages — not charity, which can undermine dignity, but wages, which demand work and cultivate pride.

The apprentices were not only taught skills; they were shown that their hands could make things that mattered. The press’s apprentices printed a small paper every month by their hands and wits, featuring stories from the streets. The paper’s voice was raw and honest. Parents bought it for family members who had once been at sea and who liked a story that sounded like the world they knew. The apprentices learned to see themselves as contributors; they were no longer merely taking crumbs from the city’s table.

Jonah did not forget the past. He visited the places where he had once slept and the bridges where the river whispered secrets. He found Thomas working as a baker’s assistant and made sure the man received a small stipend to learn to count. Lena, older and fierce, had been taken in by a seamstress who paid her a pittance but taught her a craft. Big Ben had been in trouble with the law for a petty robbery but was now cleaning a stable and dreaming of better things. Jonah used his network to help them get apprenticeships at the press, bakery, and the tailor’s shop. He was not sentimental about rescue; he believed in practical steps.

Years moved. The apprentices grew into men and women who taught the next cohort. The press’s small school expanded into a proper evening class. Jonah became the person who could balance ledger and scold with equal measure. People who had once dismissed him as a nameless boy now said his name with a touch of respect. He never forgot the city’s cruelty; he never stopped sleeping badly when it thundered. But he had learned to build defenses: institutions that were small but robust enough to catch those who fell.

The city, in turn, was not static. It shifted in ways that were both sudden and gradual. Laws were passed that made workhouses marginally better; inspectors visited factories more often; hospitals had to disclose some data. The press continued to wrestle with authority. Jonah and his colleagues sometimes arranged for clandestine prints to push the city’s conscience further; sometimes they used polite argument. They learned that change was not a single loud scream but an ongoing conversation, a string of small acts that gather into policy.

Then one morning, long after his name had become a small part of the city’s vocabulary, Jonah encountered a boy on the bridge who had the same hollow look he had once carried. The boy’s coat was thin; the boots had holes. He watched the child as if watching a self he had once been and wished he could scoop him up and pass him a map to a safer life. But maps are not always tangible. Jonah bent to the child’s level and offered him the maroon book.

“This is yours,” he said to the child.

The child blinked. “It is wet,” he said.

“It was wet and then it dried,” Jonah replied. “That’s a life.”

He took the boy to the press, where the apprentices were setting type for the next month’s paper. Jonah watched as the boy’s fingers tentatively touched the trays of letters. The room hummed. Jonah felt the old thrill: the small hand that learns to shape the world. He promised himself to keep the press’s doors open, to make sure that the city’s children had places not just to survive but to find meaning.

There was a climax to the life Jonah had chosen, though it arrived not as a singular hero’s battle but as a test of endurance that required him to gather all the things he had learned. The test came in political form: a campaign to close “informal institutions” as part of a drive to make the city more “orderly.” The campaigners were men in clean coats who had never met a night they could not sleep through. They called for children to be placed in workhouses and for institutions like Jonah’s press to be dissolved because, the papers said, they encouraged “subversive behavior.” The magistrates were tempted by the logic of tidy control.

For a while it seemed that the city might backslide. A coalition of the powerful men argued in Parliament to tighten regulations, and inspectors came to the press with stern faces and the smell of officiousness. Jonah was called before a committee. He felt the old cramped terror of accusation: the possibility of being evicted from the central role he had carved out for himself. He realized in that moment how fragile the web of kindness was when the state decided to tighten its fist. He had been building a world that relied on goodwill; goodwill can be retracted.

But he also understood something else now that he had not at ten: that the press’s work was not merely benevolence but a force. He had witnesses. Children he had taught testified. Doctors spoke about the lives saved by the pamphlet campaigns. Parents spoke about wages improved. The testimony was messy and human, not the clean metrics of men in committees but a chorus of ordinary voices that made the clean men uneasy.

The committee could have closed them easily, but in the process they learned that closure exacts its own costs. The press became a battleground. Jonah did not fight with shouts. He fought with the patient logic of evidence and the moral pressure of those whose lives had improved. The committee could not dismiss the band of witnesses who had once been nameless and now spoke with dignity. Public sentiment shifted when the newspapers printed the testimony of clergymen, washerwomen, and ex-factory workers. In the end the committee recommended reforms that preserved some of the press’s activities while imposing limits intended to satisfy the clean men. It was a compromise Jonah did not love but could live with.

The struggle exhausted him in ways he had not expected. He found that a life filled with resistance demands energy and grace. He also discovered that victory is often small: a clause changed here, a stipend kept there, a child allowed an apprenticeship. He learned the art of celebrating incremental wins.

Years later, Jonah walked beneath the same bridge where he had once slept and looked at the maroon book on his shelf, its binding faded, the pages worn with his handwriting and those of others. He sat on the bench and opened it, the city breathing around him like a living thing: the clatter of carts, the bell of a distant ship, the smell of coal. He read through the entries: Agnes’ list of favourite passages, Clara’s notes on sanitation, Elias’ scribbled jokes, the apprentices’ short stories. It was no longer merely the thing that had comforted him; it was an archive of a life braided into other lives. He traced a line where, years earlier, he had written his first name — the one the reading circle had given him. The book had become more than a personal talisman; it was a ledger of small mercies and a map of changing hearts.

He had children now who worked at the press like apprentices and some who were his. He had saved enough to keep the Marlowe room functioning; he had not, of course, become a person of wealth. The press remained modest. But they had built a network: a hospital that printed its own pamphlets, a delivery route that doubled as a training ground, a bank account small but sufficient for emergencies. Jonah’s life, in the arithmetic of the city, resembled a different kind of wealth: he could, if he wished, sit in a paneled room and rest. He chose instead to continue to teach.

There is a time when the city seems to present you with the ultimate test of whether you will be like the city or whether you will try to edge it toward something better. Jonah faced it when Lena fell ill and a factory owner tried to buy her silence with money and a promise of small work. She refused the money because she had learned to not sell the dignity she had won with sharpened hands. Jonah defended her because he had once been small and because he understood that the most important victories are the ones people choose for themselves.

Lena lived and eventually became a master seamstress who trained girls from the orphanage. Thomas opened a bakery that offered free bread to anyone who could show proof of being an apprentice. Big Ben started a small stables co-op. Jonah’s pride was not paternal in a classical sense but rather that of a man who had helped build a village from stray bricks: he saw where the places were where people could be caught before they fell into the gutters of the city.

The story’s climax is not a single blaze of glory but a gathering of consequences that demand courage: the committee’s threat, the fever, Agnes’ death, Clara’s passing, the raid on the press, the factory collapse. Each event required small monumental decisions. In all those times Jonah had to choose whether he would act on the principle he had been given in a maroon book and in Agnes’ unassuming face — that lives are leaky things that can be patched with care and with stubbornness.

The humane ending — not saccharine, not a fairy tale — arrives as a slow unrolling of consequence that makes the protagonists recognizable and alive. In Jonah’s middle years he married not with ceremony or effusive vows, but with a quiet arrangement with a woman named Margaret, who had worked as a courier and had the manner of someone who kept chaos organized. They had a child, a small, stubborn boy who laughed like a bell and fell often but was given a steady hand. They named him Thomas after the baker. The name was both homage and promise: that name, like others, could be a bridge.

Jonah never forgot the moments of hunger. He kept a slab of the city’s past tucked into his memory like a stone that reminds you of where the shore used to be. He taught the boy to feel the weight of a loaf before handing it to someone, to see value not only in coin but in time. He told him stories — not fictions about princes but the real epics of small people who had learned to be brave: Agnes folding paper, Clara carving time from hospital wards, Elias cracking a joke when the press was under scrutiny, Lena threading a seam like she was mending the world.

As the city’s chimneys changed their breath — coal giving way to newer fuels, the alleys inching toward sanitation and then toward other problems — Jonah’s press adapted. The apprentices he had trained began to run workshops in neighboring neighborhoods. They taught children how to read their wages, how to write petitions, how to arrange type. The reading circle became a small network of community rooms. It was not utopia, but it was a city remade in small areas, a patchwork of better things.

In the last pages of the maroon book, Jonah wrote a list. Not of names for committees or of ledgers of debts, but of small things he wanted to remember: “1. Protect the children’s evening class. 2. Keep the infirmary pamphlet fund alive. 3. Teach apprentices to read aloud.” The list was perhaps ordinary until you count how many lists fail for the lack of people who actually keep them. Jonah kept this list like a gardener keeps seed packets.

He died not on a foreign battlefield nor on a marble floor, but in a quiet room above the press, in a bed lined with the gathered faces and sounds of a life. Margaret held his hand and read aloud from a book Agnes had loved. The apprentices and the old reading circle members came and placed their palms on his wrist and told him what he had changed. They told stories of how a child with holes in his boots had become the man who taught them how to set type. They were not extravagant: their words were practical, precise, and honest. Jonah listened. He had always preferred being observed by other people’s lives rather than by flattery.

When he passed, the city — which is a creature of indefinite affection and sharp neglect — gave him something small and meaningful: a corner of a park named after the Marlowe reading rooms. Children played there and read on benches. The apprentices kept the press running. The hospital still printed pamphlets. The apprentices eventually became the press’s board, and the board occasionally shouted about budgets.

The humane ending comes from the residue of decisions: a life that started in the gutter and ended in a community that could hold others. It is humane because Jonah never obliterated the memory of the city’s cruelty, but he transformed it into a grammar for kindness. He did not rescue everyone; he could not apply balm to every wound. But he did what one person could: he made structures that improved the odds, that taught hands to make things that mattered, that placed the maroon book in the hands of a child on a bridge and said, simply, “It is yours.”

The maroon book found other readers afterward. A child who had once been a thief turned into a typesetter, then an editor. A woman who had been a washerwoman wrote a pamphlet about wages. Their names changed, and their children changed, and the city shifted as slowly as a tide. The story was not finished — no story of a city ever is — but it bent a little toward kindness in the places Jonah touched, like metal warmed and then reshaped.

He had learned, in the long arithmetic of survival, that small acts compound. A cup of tea, a bed for the night, a line of type, a pamphlet on sanitation: these were not grand gestures, but they were the stitches that mended a life. He had known hunger and cold and the way the city had looked at him like a thing of weather. He had refused to become only what it expected him to be. He had taken a maroon book from the gutter and turned its life into a ledger of mercy.

When the young boy on the bridge — the next anonymous one — asked Jonah whether he could take the book, Jonah said, “Yes.” He added, as if stating an obvious law, “Read it. When you are ready, give it away.”

That is the humane ending: a story that does not promise paradise but insists on an unglamorous dimension of human work. It insists that people are remembered by more than their beginnings and that a city’s temperament can be altered by the patient application of small, earnest hands. The boy with holes in his boots grew into a man who taught others to read not only words but possibility. He left a city that remained flawed but a little more capable of mercy.

The maroon book remained on a shelf in the press for decades. It acquired notes in different hands: recipes, small maps, lists of children who needed beds, lines from poems. It became a communal object, a way for people to leave messages to one another across time. If you ever walked into that press and opened the maroon book, you might find this line, written in Jonah’s firm, slightly crooked hand:

“We are not merely what we survive. We are what we teach others to survive.”

And somewhere in the city, on a warm bench beneath a lamp that once belonged to Agnes’ block, a child opened a small book and read the first line and, for a minute, believed that the world could mend.

News

On 30 January 1934 at Portz, Romania Eva Mozes and her identical twin sister Miriam were born on 30 January 1934 in the small village of Portz, Romania, into a Jewish farming family whose life was modest, close-knit, and ordinary.

Relocate. The word floated into Eva’s ears as if wrapped in wool, muting its severity. She was ten. How could…

She was nearly frozen to de@th that winter—1879, near Pine Bluff, Wyoming—curled beside the last living thing she owned: one trembling chicken pressed tight against her chest.

She worked like a woman born older. She fetched firewood, each log a promise. She mended the roof where the…

Gillian was only seven years old when the world decided there was something fundamentally wrong with her.

The people behind the glass moved and leaned. The mother’s face softened until she looked very young, like someone remembering…

“Come With Me… The man Said — After Seeing the Woman and Her Kids Alone in the Blizzard”

Marcus kept his voice low; low voices never sounded like danger. “My place is ten minutes from here,” he said….

single dad accidentally saw his boss topless at the beach and she caught him staring

What the note did not prepare me for was the way looking at Victoria would become a private weather system…

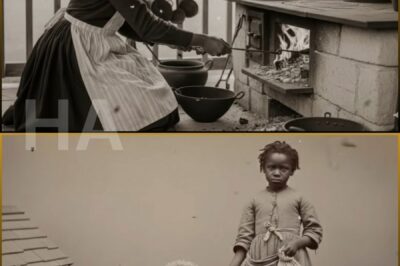

(1856, Sara Sutton) The Black girl who came back from the de@d — AN IMPOSSIBLE, INEXPLICABLE SECRET

Sarah rose like a thing that had been to the edge and found a way back. Mud clung to her…

End of content

No more pages to load