While other girls asked for dolls or ribbons, Margaret wanted a jackknife. A gimlet. Bits of scrap wood. She liked the smell of shavings on the floor and the sound of a blade biting cleanly into grain. She built sleds for her brothers and kites that flew higher than anyone else’s. If something broke, she took it apart. If she could not put it back together immediately, she kept trying.

Later in life, she would say, “The only things I wanted were tools.”

At the time, no one thought of that as a destiny. It was just a quirk.

Then her father died.

Margaret was still a child when the family’s modest stability vanished. Hannah Knight, suddenly a widow, packed what little they owned and moved the family to Manchester, New Hampshire, where textile mills promised work.

Promises were cheap. Labor was not.

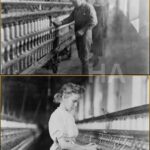

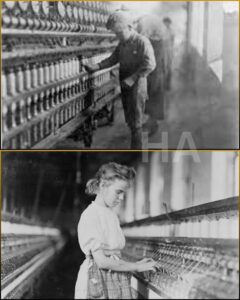

At twelve years old, Margaret entered the cotton mills.

The mills were loud enough to erase thought. Machines clattered and shrieked from dawn to dusk, belts snapping overhead like living things. Children worked beside adults. Fingers were lost. Limbs crushed. Lives ended without ceremony.

One winter afternoon, Margaret saw a boy no older than herself step too close to a loom. A steel-tipped shuttle shot free like a bullet and struck him. The sound it made when it hit flesh stayed with her for the rest of her life.

She did not scream.

She watched.

That night, she could not sleep. The next night, she began sketching. She imagined a restraint, a mechanism that would sense failure and stop the machine automatically. She had no formal training. She had no permission. She had only urgency.

Within weeks, she had built a working model.

The shuttle restraint system was simple, elegant, and devastatingly effective. When something went wrong, the loom stopped. Word spread. Mill owners adopted it quickly. Accidents dropped.

Margaret was twelve years old.

She received no payment. No patent. No recognition.

But she learned something far more valuable.

Ideas mattered. And if you did not protect them, someone else would take them.

Learning Without Being Taught

Margaret never returned to school in any formal sense. Life did not allow it. But she educated herself relentlessly.

Through her teens and twenties, she worked wherever hands were needed and curiosity tolerated. She repaired furniture. She upholstered chairs. She engraved metal. She learned photography, chemistry, drafting. She studied machinery the way other people studied scripture, absorbing principles by touch and repetition.

Men laughed sometimes when they realized she knew more than they did.

She learned to ignore laughter.

Every job taught her something. Every failure sharpened her instincts. She did not think of herself as extraordinary. She thought of herself as prepared.

By the time she was twenty-nine, Margaret Knight had accumulated a body of knowledge that most engineers never achieved, because hers was not theoretical. It was earned.

In 1867, she took a job at the Columbia Paper Bag Company in Springfield, Massachusetts.

The pay was insulting. The conditions were loud and monotonous. But within days, Margaret noticed a problem that no one else seemed willing to solve.

Paper bags.

They made thousands of them, but they were all the same. Thin, envelope-shaped sacks that collapsed the moment anything heavy was placed inside. They were fine for letters. Worthless for groceries, hardware, or bulk goods.

Flat-bottom bags existed, but they were folded by hand, one at a time. Slow. Costly. Inefficient.

Margaret watched workers fold until their fingers cracked. She watched merchants complain. She watched management shrug.

And she thought, This is ridiculous.

The Machine No One Believed In

Margaret began sketching at night.

At first, the idea was abstract. Then the shapes became clear. Blades to cut. Arms to fold. Plates to press. A timed application of adhesive. All synchronized.

Within a month, she had a complete conceptual design.

Within six months, she built a wooden prototype in her rented room.

It was rough, improvised, held together by faith and clamps. But when she fed paper into it, the machine cut, folded, and glued flat-bottom bags automatically.

It produced one thousand bags.

Margaret stared at them in silence.

She knew then that she had something that would change everything.

But wood was not enough. A patent demanded iron, precision, permanence.

She hired a machinist.

Then another.

She moved to Boston, where she refined the design with two more skilled men who respected her mind even if the world did not. She paid them with money she could barely spare, supervised every cut, adjusted every measurement.

At one shop, a man named Charles Annan stopped by.

He was polite. Curious. Asked intelligent questions. Requested a demonstration.

Margaret, focused and tired, obliged.

It did not occur to her that curiosity could mask theft.

Betrayal in Black Ink

When Margaret finally filed her patent application, she expected a process, perhaps resistance, maybe delay.

She did not expect rejection.

A clerk informed her that the patent had already been granted.

To Charles Annan.

The machine was nearly identical. The claims mirrored her own. The timing was precise enough to leave no doubt.

Margaret felt something close to grief, then something colder.

She hired a lawyer.

She did not cry. She did not plead. She prepared.

Four years of notebooks. Diaries. Dated sketches. Photographs of early models. Testimonies from machinists. Everything she had ever written, drawn, or built.

She packed them carefully.

Then she went to Washington.

Sixteen Days That Changed History

The trial lasted sixteen days.

Margaret spent one hundred dollars a day on legal costs. A fortune. Every dollar represented hours of labor, sacrifice, restraint.

Annan’s defense never changed.

A woman could not have designed such a machine.

He said it calmly, repeatedly, as if stating a law of nature.

Margaret responded with evidence.

She walked the court through each component. Explained each mechanism. Produced notebooks dated years before Annan’s involvement. Presented witnesses who testified under oath that she had dictated specifications, corrected errors, and demonstrated mastery.

One machinist said, “She knew more about the machine than anyone in the shop.”

Another said, “We built what she told us to build.”

Annan produced nothing.

No drawings. No journals. No witnesses. Only belief.

The judge listened.

When the verdict came, it was swift.

Margaret Knight won.

On July 11, 1871, she received U.S. Patent No. 116,842.

She became the first woman in American history to win a patent interference lawsuit.

A Legacy Larger Than Profit

Margaret co-founded the Eastern Paper Bag Company and negotiated a settlement. Two thousand five hundred dollars upfront. Royalties capped at twenty-five thousand.

It was more money than she had ever seen.

She sold the rights and walked away.

Business bored her. Invention did not.

Her machine transformed commerce. Strong, flat-bottom bags carried groceries, tools, books. Workers packed lunches. Students carried sandwiches. Stores expanded.

The brown bag became a fixture of daily life.

Margaret continued inventing.

Dress shields. Window frames. Shoe machines. Cooking devices. Engines.

By her death in 1914, she held at least twenty-six patents and claimed eighty-nine inventions.

People called her the “woman Edison.”

She disliked the phrase.

She signed every patent with her full name.

Margaret E. Knight.

She never married. She lived independently. She taught children. She mentored quietly. She refused to hide.

Queen Victoria honored her. Smith College recognized her work.

But her greatest achievement was simpler.

She proved that competence has no gender.

That evidence outlasts arrogance.

That a woman with tools, patience, and courage could reshape an industry.

The Bag in Your Hand

Every flat-bottom paper bag you have ever held traces back to her.

Every grocery sack. Every lunch bag. Every quiet convenience.

They exist because Margaret Knight refused to accept limits placed upon her.

At twelve, she saved lives.

At thirty-two, she stood in court and spoke through proof.

She did not shout. She did not beg. She simply showed the truth.

And the truth was enough.

Remember her name.

Not as a comparison.

Not as a footnote.

Just as Margaret E. Knight.

The inventor who proved them all wrong.

News

🚨UPDATED WITH TODAY’S SHOCKING ESCALATION: A Single Impeachment Move in Washington Ignites a Science-Vs-Power Firestorm No One Saw Coming

A Single Impeachment Move Ignites a Science-Vs-Power Firestorm in Washington Updated with today’s escalation, the showdown over HHS Secretary Robert…

🚨UPDATED WITH TODAY’S EMOTIONAL RIFT: Vivian Jenna Wilson’s Break From the Musk Legacy Sparks a Shockwave No One Saw Coming

In a world fascinated by the lives of billionaires and their families, it is rare to see the child…

🚨TONIGHT’S UNPRECEDENTED BROADCAST SHATTERS HOLLYWOOD’S SILENCE: Tom Hanks Breaks His Lifetime of Restraint as Virginia Giuffre’s Death Forces a Reckoning No Power Broker Can Halt

Tom Hanks Shocks the World: The Night Hollywood’s Golden Boy Delivered a Truth Bomb No One Expected Last night, television…

🚨UPDATED WITH TODAY’S ESCALATING SHOWDOWN: Diddy’s $1 Billion Defamation Strike on Netflix Sends Shockwaves Through Hollywood’s Gatekeepers

Diddy vs. Netflix: Inside the Billion-Dollar Defamation Battle Reshaping Celebrity Power, Media Ethics, and the Ownership of Personal Narratives When…

🚨UPDATED AFTER TONIGHT’S JAW-DROPPING MOMENT: Colbert’s $10 Million Confrontation with Power Sends Shockwaves Through NYC’s Elite Gala

SHOCKING SPEECH: STEPHEN COLBERT STUNS BILLIONAIRES WITH TRUTH AND $10 MILLION! Colbert Drops a Moral Bombshell at NYC Gala, Leaving…

🚨UPDATED WITH TODAY’S JAW-DROPPING TURN: Swift & Colbert’s $30 Million Leap of Faith Stuns America and Ignites a National Conversation No One Saw Coming

$30 Million of Meaning: How Stephen Colbert and Taylor Swift Lit Up America With One Extraordinary Act of Humanity There…

End of content

No more pages to load