The people behind the glass moved and leaned. The mother’s face softened until she looked very young, like someone remembering a secret. The psychologist’s mouth closed. Mr. Archer turned off the radio and smiled the way one smiles when a riddle is solved.

“She is not sick,” he said. “She is a dancer.”

Those words changed everything.

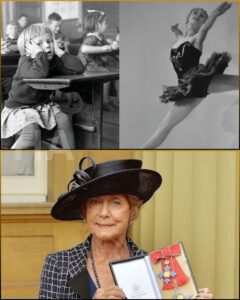

Acceptance came not as a thunderbolt but as a slow thaw. Gillian’s mother, who had long ago stopped expecting miracles but kept hoping for ordinary kindnesses, signed her daughter up for lessons at the local dance school. In that first class, in a high-ceilinged studio with mirrors like lakes, Gillian felt a recognition so profound it was almost painful. Music moved her from inside out. Her restless limbs found instruction and shape; they were not restrained but guided. In the barre exercises she found arithmetic that mattered. In the pirouettes she found questions with answers. Every step was a grammar, every jump an exclamation.

Time in those early years unfurled like rehearsed choreography. Teachers noticed. One of them — stern, intense, a woman with an eye for composition — taught Gillian to hold still shockingly well. The school that had once branded her “distracted” now applauded, and Gillian’s first professional contract came earlier than anyone had expected. At sixteen she stepped onto a stage as one among many, a body in motion within a living picture. The applause was like another translation of the music inside her; she felt known.

The early success was its own kind of weather. It brought her down stage curtains and up bright staircases to the West End, where she learned that motion on a grand scale required more than athletic grace; it demanded imagination, patience, and the ability to see other people’s inner movements and turn them into company-wide language. Gillian’s restless energy now had purpose — an electric current channeled into choreography.

It would be a truth of her life that the great leaps are sometimes achieved by people who had been told to be smaller. She learned the craft of making other bodies speak; she learned how to sculpt silence and set it in motion. She took T.S. Eliot’s images and, later, whole new mythologies, and she made them breathe: an arched shoulder that said hunger, a slow, lateral creep that suggested feline gravity, a lift of the chin that was a constellation of pride. Her work was at once minimal and unapologetically theatrical; critics called it a conjuring.

But success, though dazzling, was not balm enough.

In the years after her arrival on the theatre scene, Gillian discovered a pattern: the very restlessness that had first been her salvation could also be a tyrant. She worked with fever and precision, but exhaustion came like a persistent shadow. Her body, which had been the temple of her art, sometimes betrayed the most intimate errands—ankles swelling, a strain that would not heal. The more her name became known, the more the world wanted to contain her talent in categories. Directors asked for predictable spectacle; producers wanted reliable formulas; audiences wanted their ideas confirmed. Gillian, who loved the unexpected, found herself negotiating the compromises between commerce and imagination.

The real crucible arrived in a winter when the air turned metallic and London streets glinted with early frost. She was invited to choreograph a new production for a composer who was already famous for large theatrical gestures. The composer wanted a spectacle: something to fill the lungs of a vast theatre, to make critics put on their best coats and sit up straighter. He wanted music that roared and a chorus that could drown doubts.

Gillian read the score and felt the muscle of it. There were sections that demanded human locomotion to become architecture, moments that required bodies to make landscapes. She imagined a city unfolding onstage, people moving like tides. She said yes.

From the first rehearsal the production chewed at her like a machine. The composer’s demands were inhuman. The director wanted her to render humanity into patterns to match the orchestra. The lead performer, an actor of great statures and small patience, resisted gestures that did not reflect his public persona. Gillian found herself explaining, cajoling, pleading. When the dancers moved as she wished, the director wanted more simplicity. When she offered subtlety, the producer worried the audience would sleep. Money and taste braided their expectations with the art.

At night, when she lay awake, Gillian felt the old schoolroom’s quiet judgments press against her chest. People had told her to be still, to be “normal.” Now those old voices were asking for a different kind of conformity: to make the art sell, to make the animals in the stage cage perform.

Then the accident happened.

It was not catastrophic. It did not come with sirens or gurneys. It came as an absence—an ankle tendon that frayed during a long Sunday rehearsal, a small, mortal failing in machinery that had never failed before. Gillian woke the next morning with a limp she refused to trust. She went to the hospital. The surgeon, sympathetic and measured, put a neat line of possibility into her patient file: rest, therapy, time. The words were kind, but they were also a verdict.

For weeks the theatre pulsed on without her feet at full strength. She taught classes. She directed scenes from the sidelines. She watched from a chair as other women and men made the shapes her body used to make. She discovered that her memory of motion was both precise and treacherous. When she demonstrated, the muscles remembered; when she watched, the absence of actual performance felt like a translator trying to speak a language with half its verbs missing.

Her fear, which she hid beneath humor, was ancient: that the part of herself that had been called a problem would finally be declared obsolete. She feared that without the desperate urgency of constant motion she would forget what it meant to move with purpose. She feared becoming one of those older dancers whose reflection in the mirror looks like an abandoned map.

Then, in the middle of that anxiety, a conversation changed the course again.

A young dancer named Sofia, small and quick and new to the company, came to Gillian after rehearsal. She had been watching the way Gillian sometimes refused to sit still even when concussion of fatigue made her bones ache. Sofia had been a child of immigrants, her hands callused from years of work, and she moved with a speed that was half answer, half question.

“You make us move because you see something,” Sofia said. “When I dance, I feel seen. My mother always said my energy was a nuisance. You taught me it is a language.”

Gillian listened. The words were simple, but they looked like windows opening. It had been a long time—years—since she had heard that her motion was a language rather than a trouble. She found herself telling Sofia about the glass room and the old teacher who had turned on a radio. The story was small, but the telling made her whole.

Sofia’s eyes were steady. “They’ll be back,” she said. “They always come back when they see something they want to keep. We’ll show them.”

This tiny faith lifted her out of a dark spiral. She attempted small things: altered steps, new phrasing, a scene reworked to put the chorus in front of the orchestra instead of behind it. She found ways to translate movement into narrative that did not require her to be the one always performing.

And then the production opened.

The first night came like a wave. The audience filled the auditorium with expectation and gossip. Critics sat with their pens and the intimacy of their practiced disdain. Industry watchers came with their own calculators of success and failure. Gillian, her ankle wrapped and taped like a secret, stood in the wings and watched her choreography bloom. The stage lights cut the air like a second sun. The orchestra swelled. For a while, the show rose exactly as she had imagined: bodies moving in surges, a city imagined in ballet and impulse, a chorus that could make laughter and mourning look like distant siblings.

But halfway through, a small mistake happened. One of the dancers missed a cue—an error as human and as ancient as breath. The lead, someone who had never forgiven errors easily, paused a dangerously long beat. Murmurs rose, subtle but sharp. In the house someone laughed, annoyed at the rupture. A critic in the front row made a note that looked like an indictment. The director, sitting in the darkened control booth, clapped his hand over the phone he had been clutching and yelled instructions into the void.

The show continued; it had to. But beneath the choreography’s bright surface, a creeping doubt had taken root. In the weeks that followed, reviewers who had come expecting praise could not find sufficient perfection. They wrote that the choreography lacked coherence, that the director had indulged in flights that had not been tethered. Others said the score was too large for the human form that inhabited it, that Gillian’s gestures were fractured by ambition. The critics’ words circulated in the city like cold air.

Publicly, sales were sustained. The theatre rarely emptied. But beneath that success crawled a commentary of failure. The reviews were not indictments of her heart; they tended, instead, to be precise little disassemblies. For Gillian, who had spent a life learning to trust the body’s voice, the criticism cut to a private bone. It reawakened the old schooling voices that had told her she was wrong.

She took refuge in work. She rewrote scenes, sharpened tempos, asked dancers to repeat until their joints hummed with certainty. Yet the more she tried to eradicate the error, the more she found the production stiffening. The art was losing its edge. Something was asking to be accepted rather than erased.

The climax of her internal struggle arrived in another small, decisive moment.

Gillian was watching a late rehearsal when she noticed a dancer at the back, a lanky boy named Tom, who had little technique but a surplus of honesty. During a break he sat on the floor and, without intending it, began to tap a rhythm with his hands on his thighs. It was uneven and unschooled, but it had heart; it was a code his body had invented to speak. Gillian sat down beside him, and without ceremony, she joined his rhythm with a clap.

They moved together like two people inventing a language on the spot. The rest of the company looked up. The director came over, eyebrows drawn; the producer came into the doorway, drawn by a different kind of interest. In that sudden, accidental duet, something clearer and truer than rehearsed perfection took shape.

After the rehearsal Gillian told the director she wanted to change the opening. He argued. He had a budget, a runtime, a poster to sell. But Gillian argued more ferociously. She said the show needed fracture as well as polish, it needed the rawness of a life not yet edited by industry taste. To do that, she would have to risk the production’s neatness.

“Risk how?” the director asked.

“Let the imperfections speak,” she said. “Let us design an opening where the chorus enters not as a machine but as a universe of small, imperfect movements. Let us make room for bodies that are not identical, for rhythms that break and rejoin.”

It sounded like an artistic manifesto. It also sounded like sabotage. The producer threatened legalities. The lead actor’s agent called her reckless. But Gillian persisted. She pushed the company through a week of epiphanic rehearsals: improvisations, late-night experiments, nights when they danced in silence and nights when they set the studio’s radio to stations from different continents. The choreography began to loosen. The dancers stopped trying to be perfect and started trying to be true.

On the night of the revised performance, the theatre thrummed with raw expectation. The opening began with a single light: an anonymous body on a bare stage. That body moved awkwardly, then poetically. More bodies followed, each with its own accent. The chorus did not arrive in formation; they arrived in fragments—someone stumbling, someone laughing, someone turning as if someplace else were calling them. The music swelled and broke and swelled again. The audience sat in an unsteady silence.

Halfway through the second act, something happened that would be spoken about for years. In the middle of a sequence that required a tight unison, one of the principal dancers—an experienced performer with a career like a polished curve—forgot the timing. Instead of stopping, he let the moment become a different gesture entirely. He made the error into a question and the company answered it with improvisation. Where there had been precise choreography there was now breath: the promise of human error turned into the proof of human presence.

The audience did not hiss; it held its breath. The air was electric, charged with the exact kind of risk that had made theatre possible since its earliest days. The applause at the end was not the polite clapping of those satisfied; it was a standing ovation that felt like a thousand small confessions. Reviewers who had come to dissect found, instead, a production that had been reborn. Critics wrote about the courage of imperfection, about a choreographer who had chosen truth over spectacle. Audiences spoke in doorways and public houses about how they had felt. The production was not perfect. It had not pretended to be. It was, in unexpectedly radical ways, human.

For Gillian, it was a vindication, but not the kind she had imagined. She did not receive endless critical acclaim or an unbroken line of triumphs. What she received was something quieter and deeper: confirmation that the body’s language—imperfect, idiosyncratic, and alive—was worth defending. She found, too, that her own role would change. She could not be the center for every movement; she could be the shepherd of many voices, the one who listened most carefully.

Years moved like braided music. Gillian worked across continents, crafting choreography that drew praise and sometimes bafflement. She collaborated with composers and playwrights, and her name was attached to productions both humble and grand. Sometimes she revisited the very shows that had once seemed to swallow her, and each time she adjusted them, pruning where necessary and leaving room for accidents.

Her life, at last, reached another kind of public recognition. She was honored by institutions that had once been distant; she received awards that had glitter but did not change the small, steady ache she carried when a dancer failed to find a phrase. The British government recognized her with a title that landed in her mailbox like a ceremonial note. It felt weighty but also, in its own way, like another act of translation: society translating the language of movement into its own ceremonious vocabulary. She accepted the honors with a mixture of gratitude and bemusement.

One of the great gestures of fate toward her was the renaming of a theatre. The New London Theatre, once the home of a show that had been as strange and alluring as a dream, reopened its doors under a new name—the Gillian Lynne Theatre. The plaque on the wall read like an epitaph and a promise in one: it would stand as a public testament to the idea that a child who could not sit still had become someone who taught many how to move.

The day the theatre was renamed, Gillian walked up its steps with her cane, for age had begun to give its gentle raids. Fans and colleagues gathered; dancers who had once been young and blinking at mirrors now moved slowly, their own lives heavy with memory. The speeches were warm; the politicians’ faces were trained into respectful angles. The cameras flashed. Gillian, who had spent a life learning to let motion speak, stood at the microphone and spoke in a voice that was at once shy and metallic with years.

She could have made the speech into a sweeping treatise, a manifesto of art and resistance. Instead she told the story of a room with a pane of glass and a radio. She told how a small act of seeing had altered the direction of a child’s life. She spoke of the teachers who had failed to understand and the one who had insisted on watching. She spoke of the dancers who had become her family and the countless small errors that had turned into beautiful accidents.

“Children who move,” she said, “are not to be restrained out of fear. They are to be listened to.”

After the speeches, she wandered into the now-named theatre, a place of velvet and old dust and dreams. In the wings she found a small figure leaning on a broom, watching the sunlight slant through the proscenium. The figure was a young dancer—someone who could have been a version of herself, or of Sofia, or of every child pushed into corners for being too much.

“You will be seen here,” Gillian said, and the young dancer smiled like someone receiving a small, sacred map.

And yet the story, like all true things, did not end with trophies and theaters. Later that year, during a rehearsal, Gillian had a fall. Her body, which had never been entirely obedient to ordinary commands, finally declared its age. She broke a hip. The injury was severe, and recovery was uncertain. In the hospital she lay and thought of children tapping at classroom windows, of radios and glass, of the innumerable small interventions that had altered her life. She feared that the thing she loved most—movement—might one day become an unreachable shore.

But even in the hospital she found movement of a different kind. Nurses brought music into her room. A physiotherapist taught her tiny, precise motions to relearn walking. She found that language could be movement too; a conversation, an apology, a shared memory could move people in ways that were as transformative as any dance. Friends came to read her letters, to tell her about dancers who had been inspired. They danced, sometimes clumsily, in the hospital garden, because the need to move could not be stilled even by linoleum and antiseptic.

Her recovery was long. It required patience, a lesson that was not entirely natural for someone whose life had always moved fast. She relearned how to step and then how to leap, not with the speed of youth but with a new, deliberate grace. She watched younger dancers grow into artists she had once been. She taught them the art of listening first—listening to the silence between notes, to the breath before a movement, to the way a stuttered beat could be a threshold rather than a failure.

In her final years she still took small classes. Sometimes she would sit at the edge of the studio and hum a rhythm while feet shuffled and found their own voices. Young dancers would come and sit beside her, seeking a word, a posture, a wink. She became a keeper of a vocabulary, a curator of gestures that could be used to build worlds. Her life had become the proof that the thing that once was called wrong was, in fact, a way of living.

When she died, it was not with the tragic suddenness of some stories nor with the protracted decline of others. She passed with the kind of quiet that a theatre has after the audience has left: a hush that is not empty but full of echoes. People spoke at her memorial, and they shared stories that were small and large. A former pupil told how, as a child, she had been told by teachers that her energy was a nuisance; by the time Gillian had been through her life and hands, that pupil had become a teacher speaking to a choir of children. The stories wound like threads into a tapestry that was not easily summarized.

There was one story that people told again and again: the glass room with the radio. When they told it, they added small details that may or may not be true—what mattered was the truth within the myth. People said that the room had been ordinary, that the radio had been old and the music had been a waltz. They said that she had danced as though she had been made to do nothing else, that she had lifted herself into a language they had never heard before. The heart of the tale—an act of someone seeing another person as they are—was the thing that mattered. It became a litany: see the child who cannot sit still; listen; find the music.

Perhaps the greatest legacy she left was a simple, stubborn proposition: that the restless child is not a fault but a compass. It was not some universal cure for every difficulty—some children would still need help, some would still need medicine, support, therapy—but it suggested something that institutions often forgot: that difference might also be genius.

And so the story traveled.

It went into schools where teachers, remembering her tale, watched a tapping foot and asked, Why? It went into households where worried parents read the story and found patience. It went into theatre programs and conservatories and into the hands of young choreographers who wondered whether the narrow boxes of taste might be pried open.

Years later, in a studio far from the city where a young choreographer named Lina sat with a notebook, she penciled notes: “Make room for accidents. See the child.” Lina’s first show included a sequence where the chorus entered in staggered steps, each body in its own accidental rhythm, and the audience rose in a surprised, wholehearted standing ovation. Lina later said she was inspired by a story of an old teacher, a glass pane, and a radio. She told her dancers that perfection can suffocate the human voice.

And the story was not just about dance. Teachers in training wrote theses about alternative ways of teaching children who were labeled. Pediatricians and psychologists debated it. Some said it was romantic—a nice anecdote that obscured the hard realities of neurodiversity. Others said it was necessary, a moral to be stitched into how caregivers and educators construct the world.

What mattered most, the ones who had been there said, was that someone had once looked at a child out of step with the world and chosen to listen rather than silence. That decision produced a lineage of people who learned to value different cadences of living.

There were contradictions in her life, of course. She was not a saint. She had been impatient. She had made mistakes like anyone—squabbles with collaborators, moments when her temper boiled over in the cramped spaces of rehearsal. She had also been lavish with praise when others deserved it and miserly with affection when she wanted privacy. She loved the limelight unfussily but disliked being reduced to a single story. She remained, to the end, vexed that an entire life could be summarized by one small miracle of recognition.

And yet in the way that only human lives can be known, the story of Gillian’s early discovery and subsequent career became a kind of myth whose purpose was neither to praise nor to condemn but to remind. It reminded people that sometimes the most inconvenient energies are the ones that, if not flattened, will lift entire communities to more generous views of what is possible.

On the anniversary of the theatre’s renaming, there was a small celebration. Dancers and theatergoers brought bouquets and wore simple dresses. They performed a sequence that gathered moments from her life: the tapping child at the window, the solo in the sunlit room with a radio, the collective improvisations that had remade a production from the inside. Parents brought children with eyes full of questions. An elderly man — perhaps a Mr. Archer who had long since retired — sat in the front row, his hands folded as if in prayer.

At the end of the program, a young girl no more than seven walked to the center and, to the astonishment of everyone, performed a small, unclassifiable movement she had invented: it was part dance, part stretching, part a bird deciding how to land. The room watched. People felt themselves leaning forward, willing the world to be generous.

Gillian lived long enough to see that performance in video. When she watched it, her eyes filled with a slow, tender light. She wrote a letter to the girl that someone later read aloud: “Keep moving. Keep telling us with your limbs what words cannot. You belong to yourself.”

If there was a single thread that ran through her life it was this: the conviction that to see is to give permission. For a restless child, permission can be everything. It can be an allowance to try, to fail, to invent a body-language of one’s own. It can be a small mercy that alters the trajectory of a life and, through that life, the world.

In the end, the story that people remembered was not only about a name on a plaque or a house of velvet and light. It was about the dozens, hundreds, and thousands of small recognitions that weave the fabric of a more humane world. It was about teachers who look up from their ledger books to the bodies in front of them. It was about mothers who—despite their own fear, exhaustion, and the pressure of authority—dare to trust a child. It was about a country that can honor movement in its institutions, and communities that can expand to hold difference.

And so it went, in many versions and small changes. Children read about a girl who danced in a room with a radio and who grew to shape stages that held a multitude of voices. They read about a teacher who opened a door and in doing so allowed the world to change its mind about what counted as talent. They learned, perhaps, that sometimes the right answer to a child’s restlessness is not to quiet them but to hand them a radio and a room.

May every child who feels misunderstood encounter someone who sees them — who looks through the glass and hears the music. And may that person, whether teacher or parent or friend, have the courage to turn on the radio.

News

On 30 January 1934 at Portz, Romania Eva Mozes and her identical twin sister Miriam were born on 30 January 1934 in the small village of Portz, Romania, into a Jewish farming family whose life was modest, close-knit, and ordinary.

Relocate. The word floated into Eva’s ears as if wrapped in wool, muting its severity. She was ten. How could…

She was nearly frozen to de@th that winter—1879, near Pine Bluff, Wyoming—curled beside the last living thing she owned: one trembling chicken pressed tight against her chest.

She worked like a woman born older. She fetched firewood, each log a promise. She mended the roof where the…

He was no more than ten years old when the streets of Victorian London became his only home. No name anyone cared to remember, no family waiting, no warm bed calling him back.

He had one treasure: a small, slim book with a maroon cover, its pages begun but never finished. He found…

“Come With Me… The man Said — After Seeing the Woman and Her Kids Alone in the Blizzard”

Marcus kept his voice low; low voices never sounded like danger. “My place is ten minutes from here,” he said….

single dad accidentally saw his boss topless at the beach and she caught him staring

What the note did not prepare me for was the way looking at Victoria would become a private weather system…

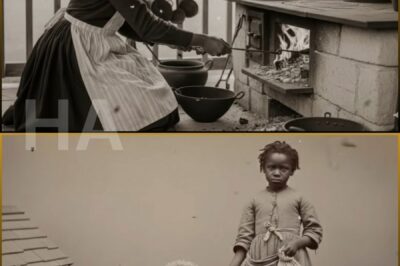

(1856, Sara Sutton) The Black girl who came back from the de@d — AN IMPOSSIBLE, INEXPLICABLE SECRET

Sarah rose like a thing that had been to the edge and found a way back. Mud clung to her…

End of content

No more pages to load