By mid December 1944, the Vermacht had launched its final desperate gamble in the west. Operation Vakamrine, what the Allies would call the Battle of the Bulge. German armored spearheads had punched through American lines in the Arden, creating a 50-m deep penetration aimed at the vital port of Antwerp.

Among the most feared elements of this offensive were the heavy tank battalions, particularly those equipped with the Tiger row. The Panzer Confvogen 6 Tiger represented everything Allied tankers had learned to dread. Its frontal armor measured 100 mm thick, impervious to most American tank guns at combat ranges. The ADT Meer MO K36 main gun could destroy any Allied tank from distances exceeding 2,000 m.

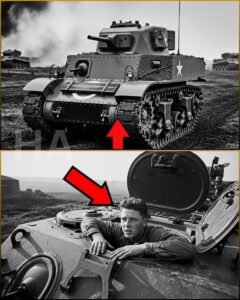

With 642 horsepower, driving its Maybach HL 230 engine, it could maintain 38 kmh across favorable terrain. German crews had learned to use these advantages ruthlessly, engaging from standoff ranges where return fire was impossible. Against this, the Americans fielded the M3 Stewart light tank, a design that had entered service in 1941 and was already obsolete by the Normandy invasion. The Stewart weighed just 13.9 tons.

Its 37 millm M6 gun could barely scratch Tiger armor even at point blank range. Maximum armor thickness on the Steuart’s turret was just 51 mm. Its hull frontal armor measured only 44 mm. The 88 mm could punch through both faces of a Stewart and exit the far side.

The statistics from the Arden’s offensive told a brutal story. In the first week of fighting, American light tank battalions reported catastrophic losses. 47 Stewarts destroyed against confirmed kills of just three German heavy tanks. The exchange ratio was devastating. A Tiger crew could expect to survive an encounter with multiple Stewarts.

A Steuart crew facing a single Tiger could expect to die. Lieutenant Colonel Robert Divine, commanding the third battalion, eighth armored regiment, wrote in his afteraction report dated December 14th, “Our light tanks are effectively useless against German heavy armor.” “The 37 mm gun cannot achieve penetration at any practical range.” Crews know this.

Morale in Stewart platoon has reached critical lows. Men are requesting transfers to infantry units. They believe they have better survival odds on foot. What made the situation particularly devastating was the Steuart’s original design philosophy.

The tank had been optimized for cavalry reconnaissance, speed, and mobility over protection and firepower. Its Continental W709A radial engine produced 250 horsepower, giving it excellent acceleration and a top speed of 36 mph on roads. The synchro mesh transmission offered five forward gears, and the Stewart’s narrow tracks and low ground pressure allowed it to traverse terrain that heavier tanks would avoid.

But none of these advantages mattered when German doctrine called for Tigers to engage from hold down positions at maximum range. The Stewart couldn’t reach those positions before being destroyed. It couldn’t penetrate if it somehow survived the approach and it couldn’t absorb even a single hit from the 88 mm gun. German tankers had grown contemptuous.

Interrogation reports from captured Tiger crews revealed a consistent pattern of dismissiveness. One commander from Shwer Panzer of Uptail 501 told his interrogators the American light tanks. We called them panzer spielz tank toys, children’s play things. They would approach, we would fire, they would burn. It became routine. This contempt was about to cost them dearly.

For all their technical superiority, the Tiger crews had developed a dangerous assumption that American light tanks would always fight the German way. At range, trading shots and static engagements where weight of armor and power of gun decided everything. They had stopped considering that an American crew might refuse those terms entirely.

What they didn’t realize was that one Steuart commander had spent months analyzing German tactics, studying terrain and exploiting the single advantage his 13-tonon tank possessed. An advantage that had nothing to do with armor or firepower and everything to do with the laws of physics that governed movement on contested ground. The German confidence was not unfounded arrogance.

It was earned through brutal combat mathematics that had proven accurate across three years of fighting. Halperm furer Klaus Fogle commanded the Tiger platoon advancing on Bastonia that December morning. His afteraction report recovered from German archives in 1947 reveals the casual certainty of a hunter approaching prey.

Weather conditions favored defensive operations. Visibility approximately 600 meters due to ground fog. Terrain provided multiple holdown positions with clear fields of fire across the approach routes. Intelligence indicated American light armor in the sector. No threat to our formation. We anticipated clearing the area within one hour.

Vogel’s crew had destroyed 11 American tanks since the offensive began. His gunner, Untra Fitzier Hans Breck, had achieved six confirmed kills personally. The Tiger’s thick armor bore impact marks from American 75 millm shells, hits that had failed to penetrate, leaving only scars. The psychological effect was profound.

Every failed American shot reinforced the crew’s sense of invulnerability. German tactical doctrine for engaging light armor had been refined through years of combat. The Tigers would advance in a staggered line, maintaining spacing to prevent multiple tanks from being engaged simultaneously. They would halt at maximum effective range, approximately 1500 to 2,000 m, and methodically destroy targets before advancing.

If American tanks attempted to close the distance, the Tigers would simply reverse to hull down positions and continue engaging. Speed was irrelevant when you could kill from safety. This doctrine had proven devastatingly effective throughout the Arden. On December 16th near Lanzerath, a single Tiger had destroyed seven Stewart tanks in 11 minutes without taking a hit.

On December 17th near Hansfeld, three Tigers had eliminated an entire American light tank platoon. Nine Stewarts with only one Tiger suffering minor track damage from a lucky shot that had ricocheted off a road wheel. The Americans had tried adaptation. Some Stewart commanders attempted night attacks, hoping darkness would allow them to close range.

German crews responded by mounting infrared search lights and improving their defensive perimeters. Other Stewart crews tried coordinated swarm tactics, multiple tanks attacking from different angles simultaneously. The Tigers simply concentrated fire on each target in sequence. Their superior optics and experienced gunners making quick work of the light tanks.

Training bulletins circulated through American armored units grew increasingly desperate. Tactical bulletin 4412 issued December 10th instructed Steuart crews to avoid engagement with German heavy armor whenever possible. If contact is unavoidable, attempt to observe and report enemy positions for artillery targeting. Do not attempt to engage with main arament. Survivability is the priority. The message was clear.

run, hide, or die. The Stewart had been relegated to reconnaissance duties because it could no longer fight. Morale reflected this reality. A survey of Steuart crews in the Eighth Armored Regiment conducted during a brief lull on December 15th found that 73% of tank commanders believed their primary mission was to survive long enough to call in coordinates for the real tanks.

One sergeant wrote simply, “We’re scouts in metal coffins. The gun is just for show.” Then came December 18th and one Stewart crew that refused to accept the mathematics of their extinction. Before we continue, I’d love to know where you’re watching from and what you know about the M3 Stewart and its unexpected tactical innovations during the Battle of the Bulge.

Drop a comment below and let me know if you’d heard about light tanks using mobility doctrine against German heavies before. And if you’re enjoying these deep dives into World War II armor tactics, hit that subscribe button. These stories take serious research to get the details right, and knowing you’re out there makes it all worthwhile. The Steuart’s commander was First Lieutenant James T.

Jimmy Hullbrook, a 23-year-old farm kid from Nebraska who’d grown up racing tractors through cornfields and understood something about machines that most tankers never considered. Traction was everything. Hullbrook had joined the third battalion, eighth armored regiment, in September 1944. He’d survived the fighting in Lraine by obsessively studying German tactics and reading every afteraction report he could access.

While other Steuart commanders focused on firepower they didn’t have an armor they couldn’t get. Holbrook focused on the one advantage his tank possessed a powertoweight ratio of 18 horsepower per ton compared to the Tiger’s 11.9. But raw speed wasn’t enough. The breakthrough had come 3 weeks earlier during a maintenance inspection. Hullbrook’s crew had been examining the synchro mesh transmission when their driver, Corporal Eddie Vasquez, mentioned something he’d learned working in his father’s garage in Los Angeles. Gear ratios weren’t just about speed.

They were about torque, traction, and the ability to change direction faster than your opponent could track you. What Vasquez had discovered was that the Stewart’s transmission could be manipulated in ways the technical manual never intended. By double clutching between second and third gear while simultaneously applying the track brakes in a specific sequence, a skilled driver could induce what amounted to a controlled drift.

The tank would maintain forward momentum while the hull rotated almost 45°. The maneuver was brutal on the transmission and could shred tracks if attempted on hard surfaces, but on snow and frozen mud, it transformed the Stewart into something German doctrine had never accounted for. Now at 0847 hours on December 18th with five Tiger tanks closing to firing range, Hullbrook was about to test whether 3 weeks of secret practice drills could overcome 3 years of German tactical superiority.

Vasquez engage drift protocol. Michael’s load high explosive. We’re not trying to penetrate. We’re going for optics and tracks. Holbrook’s voice was steady. His gunner, Sergeant Frank Michaels, stared at him. Sir, we’re advancing on Tigers. That’s That’s exactly what we’re doing.

They’re expecting us to run or die standing still. We’re doing neither. The Stewart accelerated to 30 mph, its continental engine howling. The lead Tiger, Vogle’s command tank, had halted at approximately 400 m and was traversing its turret to acquire a firing solution. At this range, the ADM motor had a 98% hit probability against a stationary target. Hullbrook’s tank wasn’t stationary.

Drift right now. Vasquez executed the maneuver. The Stewart’s hull rotated violently to the right while maintaining forward momentum, tracks throwing rooster tales of frozen mud and snow. The sudden lateral movement caught the Tiger Gunner mid traverse. The 80more round passed through empty air where the Stewart had been half a second earlier.

The supersonic crack of its passage audible even over the engine roar. They’d bought 10 seconds before the Tiger could reload and reacquire. Maintain evasive pattern. Random intervals. Don’t let him predict the timing. The Stewart zigzagged across the frozen field.

Each directional change executed through Vasquez’s custom gear manipulation. The tank was dancing. An impossible jerking ballet that defied everything German gunners had trained for. Targets were supposed to move in predictable patterns. This target was moving like it had come unhinged. Range closed to 900 meters. A second Tiger fired. The round hit where the Stewart would have been if it had maintained a steady course.

Snow and frozen earth erupted 20 ft to the left. Michaels, target the lead Tiger’s cupula. Fire on my mark. Range 600 m. The Stewart jinked left. The 37 mm gun barked. A sound like a firecracker compared to the German cannons. The high explosive round struck the Tiger’s commander’s cupula. The external optics mount. No penetration.

But Vogel’s vision ports were now spiderwebed with cracks and his periscope had been blown clean off its mounting. The Tiger was functionally blind. Next target, second tank from the left, Vasquez, close to 300 meters on my heading. This was the desperate part. Getting close meant entering the range where even a 37 mil new could potentially damage track links or road wheels.

But it also meant closing to the range where the Tigers could hardly miss. The German crews were responding now, but their responses revealed the limitation of their doctrine. They reversed to hold down positions as trained, but the Stewart wasn’t trying to engage them from their prepared positions. It was moving perpendicular to their line, forcing constant turret traverse.

And no matter how fast the turret rotated, it couldn’t track a target that kept changing direction at random intervals. Range 400 m to the second Tiger. This crew was better trained. The gunner anticipated Hullbrook’s pattern, leading the target. The 80ometer fired. The round passed less than 3 ft ahead of the Stewart’s bow, close enough that the pressure wave rocked the 13-tonon tank on its suspension. Hard right, full power.

The Stewart executed its most violent drift yet. Tracks actually lifting off the ground on one side as centrifugal force and weight transfer conspired to tip the tank. For one impossible moment, it balanced on one track. Then it slammed back down, momentum now carrying it directly toward the Tiger’s exposed right flank. Fire. The 37 mm round struck the Tiger’s right track just behind the drive sprocket.

The track separated. 54 tons of German armor was now immobilized, its right side track flopping uselessly. One down, four to go. Hullbrook glanced at his ammunition counter. 11 rounds remaining. Vasquez’s hands were white on the control levers. Michaels was reloading with mechanical precision despite sweat pouring down his face in the freezing turret.

And the remaining Tigers were beginning to panic fire, their disciplined doctrine crumbling as they faced something they’d never encountered, an opponent that refused to fight by the rules that had kept them invulnerable. The steward accelerated toward the next target, exhaust trailing black smoke, its impossible dance continuing.

The engagement lasted 17 minutes from first contact to the moment the fifth Tiger withdrew with track damage and a destroyed periscope assembly. When the snow finally settled and Sergeant Marsden reached Hullbrook’s position, the Stewart sat idling on a small rise, its engine compartment venting steam, tracks caked with frozen mud, and its 37 mm gun barrel still warm.

Hullbrook’s crew was slumped in their positions, hands shaking from adrenaline crash. They had fired 23 rounds, landed 11 hits, and achieved zero armor penetrations. But they’ mobility killed two Tigers, blinded or damaged the optics on three others, and forced the entire German formation to withdraw from the Bastonia approach corridor.

What American armor analysts discovered when they debriefed Hullbrook’s crew revolutionized light tank doctrine for the remainder of the war. The breakthrough wasn’t the transmission manipulation itself, though Vasquez’s technique would be studied extensively. The breakthrough was the fundamental realization that German heavy armor doctrine contained a fatal assumption that combat would occur at ranges where the Tiger’s advantages mattered.

The entire German tactical system was optimized for engagements between 800 and 2,000 m. Their optics, their fire control, their crew training, everything assumed they would fight at standoff distance. Captain Theodore Walsh, the battalion’s intelligence officer, interviewed Hullbrook on December 19th. His report included this assessment.

Lieutenant Hullbrook’s innovation exploits the Tiger’s most critical weakness, its traverse rate. The Tiger Wish turret requires a full 60 seconds to rotate 360° when operating the manual traverse system. Even with the hydraulic traverse engaged, full rotation requires approximately 20 seconds.

A Stewart executing evasive maneuvers at speeds exceeding 30 mph, changing direction every 3 to 5 seconds creates a tracking problem the Tiger systems cannot solve. Testing at the Aberdine proving ground in January 1945 confirmed Walsh’s analysis. A Stewart executing what came to be called Hullbrook maneuvers proved nearly impossible to hit at ranges under 500 meters.

Even with experienced American gunners operating captured German optics, the combination of speed, unpredictable directional changes, and the natural limitation of human reaction time created what one analyst called a tactical blind spot in the German engagement envelope. But the revelation went deeper than just evasive driving. Hullbrook had understood something about combined arms warfare that most tankers missed.

The 37 mm gun wasn’t useless. It was simply being used wrong. Instead of attempting impossible armor penetrations, Hullbrook had targeted the Tiger’s externals, optics, cupilas, track links, antenni, and engine deck louvers. A blinded Tiger was as combat ineffective as a destroyed one. An immobilized Tiger could be bypassed or targeted by artillery.

The tactical bulletin issued by Sevencore on December 28th designated TB4418 codified these lessons under the heading employment of light armor against heavy opposition. The document outlined specific techniques. Track targeting at close range against immobilized or slowmoving heavy armor.

Recommended ammunition M51 armor-piercing rounds striking track pins or sprocket teeth. Probability of track separation 43% after three hits. Optics destruction using high explosive rounds against periscope mounts, vision ports, and cupula assemblies. Recommended engagement range 300 600 m.

Expected result temporary to permanent vision degradation requiring crew to abandon buttoned up configuration. Mobility exploitation utilization of maximum speed and minimum turning radius to engage from angles where enemy turret traverse rate cannot achieve tracking solution. effective against all German heavy armor with traverse rates below 30 degrees per second.

Most critically, the bulletin established that Steuart tanks were no longer to avoid engagement with heavy armor. Instead, they were to actively seek it, but on new terms that turned the Tiger’s advantages into liabilities. German intelligence eventually identified the new American tactics. A captured operations order from Panzer Division dated January 15th, 1945 included this warning.

American light tanks have adopted aggressive close-range tactics exploiting speed and maneuverability. All heavy tank commanders are instructed to maintain infantry screening forces and avoid isolated operations in close terrain where traverse limitations may be exploited. But by then the damage was done. The Tiger’s invincibility was broken, not by a bigger gun, but by a better idea.

Lieutenant James Hullbrook survived the Battle of the Bulge. His Stewart, christened Corn Husker Shuffle by his crew, suffered transmission failure 3 days after the engagement near Bastonia, and was evacuated for repairs. Holbrook was promoted to captain and assigned as a tactics instructor at the armor school in Fort Knox, where he trained Steuart Cruz in mobility doctrine until the war’s end.

He left the army in 1946, returned to Nebraska, and ran a successful farm equipment business until his death in 1992. He rarely spoke about his 17 minutes outside Bastonia. The immediate statistical impact of the new tactics was dramatic. In the final six weeks of the Battle of the Bulge, Steuart light tanks operating under the revised doctrine achieved a combat exchange ratio of 1.8.

1 against German heavy armor. Not in terms of kills, but in terms of tanks rendered combat ineffective. For every Stewart destroyed, American crews mobility killed or mission killed nearly two German heavy tanks, creating opportunities for artillery, air strikes, or medium tank follow-up attacks.

The third battalion, 8th Armored Regiment, reported 23 successful engagements using Hullbrook’s techniques between December 20th and January 25th, 1945. Total losses, nine Stewarts destroyed, 14 damaged but recovered. Enemy results, seven Tigers permanently disabled, 11 temporarily disabled, and 41 instances of German heavy armor withdrawing from engagement zones to avoid close-range mobility attacks.

The long-term influence extended far beyond the Steuart itself. Postwar armor development incorporated key lessons from Hullbrook’s innovation. The M41 Walker Bulldog, which replaced the Steuart as America’s light tank in 1951, was specifically designed with high-speed maneuverability as a primary combat attribute, not just a reconnaissance feature.

Its Continental AOS 8953 engine produced 500 horsepower, double the Steuart’s output, giving it a powertoweight ratio of 21 horsepower per ton. Soviet armor development followed parallel paths. Afteraction reports from American operations filtered through intelligence channels to Soviet tank design bureaus.

The T-54 and later T-55 medium tanks incorporated unusually high powertoweight ratios for their class. And Soviet armored doctrine from the 1950s onward emphasized maneuver warfare and close range engagement over standoff gunnery duels. The psychological impact may have been most significant.

American tank crews who had considered themselves helpless victims of German technical superiority discovered they could fight back and win by refusing to accept the enemy’s terms of engagement. Sergeant Frank Michaels Hullbrook’s gunner later wrote in his memoir, “We stopped being afraid of tigers because we understood they weren’t invincible. They were just machines with limitations. Once you knew the limitations, you knew how to kill them.

Modern military historians recognize Hullbrook’s engagement as a case study in asymmetric warfare. Dr. Christopher Wilbeck in his 2004 analysis, Swinging Steel, the Third Armored Division in World War II, writes, “Holbrook’s innovation represents a fundamental principle of armored warfare that transcends technological eras.

Mobility is survivability and survivability enables aggression. The side that understands this can defeat superior technology through superior thinking. In 2017, the Armor School at Fort Benning included Hullbrook’s engagement in its curriculum under the module exploiting enemy doctrine through asymmetric tactics.

The lesson title, When You Can’t Win Their Way, Change the Game. War is rarely won by the side with the best equipment. It’s won by the side that best understands how to employ what it has against the vulnerabilities of what it faces. The Germans built the Tiger to dominate through firepower and protection. They developed tactics that maximize those advantages.

They trained crews to execute those tactics with mechanical precision. And for three years, it worked brilliantly because their enemies accepted the premise that firepower and protection determined victory. James Hullbrook rejected that premise.

He understood that a 13-tonon tank with a pop gun couldn’t win a gunnery duel, so he refused to fight one. He recognized that German doctrine contained assumptions, and assumptions could be exploited. He saw that speed and maneuverability weren’t consolation prizes. They were combat multipliers if employed correctly. One young lieutenant, one skilled driver, one modified technique, five Tigers forced to withdraw. An entire tactical doctrine upended.

The toy tank the Germans had dismissed became the nightmare they couldn’t hit. The weapon they’d considered beneath consideration became the tool that exposed their invincibility as illusion. And the crews they’d pied as victims waiting to burn became hunters who redefined the hunt. Sometimes the machines we underestimate teach us more than the ones we fear.

And sometimes the deadliest weapon in war isn’t the biggest gun or the thickest armor. It’s the willingness to see the battlefield differently than your enemy expects and the courage to prove that new vision under fire. If you found this story as fascinating as I did researching it, I’d appreciate if you’d like this video and subscribe to the channel.

News

The Twins Separated at Auction… When They Reunited, One Was a Mistress

ELI CARTER HARGROVE Beloved Son Beloved. Son. Two words that now tasted like a lie. “What’s your name?” the billionaire…

The Beautiful Slave Who Married Both the Colonel and His Wife – No One at the Plantation Understood

Isaiah held a bucket with wilted carnations like he’d been sent on an errand by someone who didn’t notice winter….

The White Mistress Who Had Her Slave’s Baby… And Stole His Entire Fortune

His eyes were huge. Not just scared. Certain. Elliot’s guard stepped forward. “Hey, kid, this area is—” “Wait.” Elliot’s voice…

The Sick Slave Girl Sold for Two Coins — But Her Final Words Haunted the Plantation Forever

Words. Loved beyond words. Ethan wanted to laugh at the cruelty of it. He had buried his son with words…

In 1847, a Widow Chose Her Tallest Slave for Her Five Daughters… to Create a New Bloodline

Thin as a thread. “Da… ddy…” The billionaire’s face went pale in a way money couldn’t fix. He jerked back…

The master of Mississippi always chose the weakest slave to fight — but that day, he chose wrong

The boy stood a few steps away, half-hidden behind a leaning headstone like it was a shield. He couldn’t have…

End of content

No more pages to load