The Hand That Refused to Disappear

The afternoon light in Riverside Antiques arrived the way it always did: tired, slanted, and carrying dust like memory. It slipped through the grimy front windows and settled on the mismatched furniture, the chipped china, the lives that had outlived their owners.

Thomas Reed paused with a ledger in his hands.

Twenty-two years in the business had trained him to recognize the ordinary at a glance. Most estate-sale deliveries told their stories loudly: poverty, sudden death, neglect. Others whispered of long lives neatly concluded. This shipment, salvaged from a demolished rowhouse in South Philadelphia, looked unremarkable.

Until he saw the frame.

It leaned against a cracked mirror near the back wall, larger than the rest, its walnut edges nicked but intact. The glass was clouded with age, the surface veiled in the dull breath of decades.

Thomas lifted it carefully.

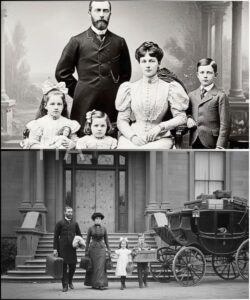

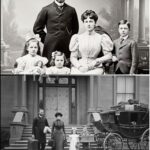

Behind the sepia haze, a family stared back at him.

Victorian era. Formal. Deliberate.

A father stood stiffly behind a seated woman. Three children flanked them, unnaturally still, dressed in their finest clothes, as if breath itself had been rationed by the photographer. The father’s posture was rigid, defensive. The children’s expressions held that peculiar mix of obedience and confusion only old photographs seem to capture.

But it was the mother who anchored the image.

She sat upright in an elaborately detailed dress, lace layered with intention rather than luxury. Her face was beautiful, but exhaustion had hollowed her eyes. They did not meet the camera. They looked beyond it, as if already seeing something the rest of the world refused to acknowledge.

Her right hand gripped the arm of the chair.

Something about that hand made Thomas uneasy.

He carried the portrait to his workbench near the window, letting natural light peel back the years. At first glance, it seemed like dozens of similar photographs he’d handled before. Likely worth fifty dollars to a collector. Maybe a bit more if cleaned and reframed.

Still, the unease persisted.

Thomas fetched his jeweler’s loupe.

He examined the photographer’s mark embossed at the bottom.

Whitmore & Sons

Chestnut Street, Philadelphia

1890

Then he returned to the mother’s hand.

Even through fading sepia, the skin texture was wrong.

Not the soft creasing of age. Not the gentle mottling of time. This was harsher. Uneven. The fingers appeared subtly bent, as if they resisted extension.

Thomas straightened.

His pulse quickened.

He removed the backing of the frame and carried the original photograph to his scanning station. The scanner hummed as it pulled the image into the present. When the file opened on his computer, Thomas enlarged the mother’s hand until it filled the screen.

His breath caught.

The skin was scarred.

Deep scars. Old burns that had healed badly, leaving discolored ridges. Small puncture wounds patterned across the back of the hand, too regular to be accidental. The fingers curved inward slightly, frozen in a shape learned through pain.

Thomas leaned back.

In two decades of handling photographs from wars, epidemics, and poverty, he had never seen anything like this.

The portrait was composed to present perfection. Respectability. Stability.

And yet that hand told a different story. A story of damage endured, not hidden.

The next morning, Thomas found himself seated in the hushed reading room of the Philadelphia City Archives. The air smelled faintly of paper and restraint. He flipped through an 1890 business directory, tracing his finger down the listings.

Whitmore & Sons. Fine portrait photography. Established 1878.

Tax records confirmed the studio’s success until its closure in 1903. Business ledgers? Destroyed in a fire the following year.

A dead end.

Thomas exhaled slowly.

Without client records, identifying the family would take months, maybe years. He was closing the directory when a voice interrupted his thoughts.

“Finding what you need?”

The archivist’s name tag read Patricia Morrison.

“Not exactly,” Thomas admitted, showing her the enlarged printout.

She studied it quietly. Her gaze lingered on the mother’s hand. She reached for her magnifying glass.

After a long moment, her expression shifted.

“That hand,” she said softly. “I’ve seen injuries like this before.”

“From what?” Thomas asked.

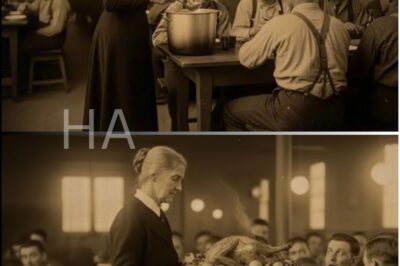

“Industrial accidents,” Patricia replied. “Textile and garment factories, late nineteenth century. Steam presses caused severe burns. Early sewing machines snapped needles like shrapnel.”

Thomas frowned. “But this family… they don’t look poor.”

“No,” Patricia agreed. “That’s what makes it unusual.”

She thought for a moment, then added, “You should speak to Dr. Helen Vasquez at Temple University. Labor history. Women’s industrial work. If anyone can explain this, it’s her.”

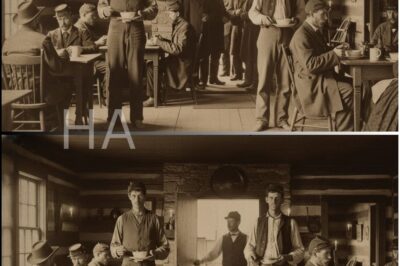

Dr. Vasquez’s office was a controlled explosion of books, folders, and framed photographs. Women hunched over sewing machines stared from the walls, their faces etched with fatigue.

She adjusted her glasses and examined Thomas’s print.

Silence stretched.

Finally, she looked up, pale.

“Where did you get this?”

“An estate sale.”

Dr. Vasquez pulled open a filing cabinet and spread out several photographs.

“Look at their hands,” she said.

Thomas did.

The scars were unmistakable.

“These women worked twelve to fourteen hours a day,” she explained. “Six days a week. Burns, punctures, deformities were common. But your photograph is different.”

“How?”

“She’s dressed like she doesn’t belong to that world,” Dr. Vasquez said. “That dress would have cost months of wages. And yet her hands tell the truth.”

Thomas swallowed. “So what does that mean?”

Dr. Vasquez hesitated. “It might mean she refused to disappear.”

She pulled out a stack of newspaper clippings.

“In 1890, Philadelphia saw several garment strikes. Most failed. The women who led them were punished harshly.”

One article caught Thomas’s eye.

“Lady Garment Workers Walk Out”

May 15, 1890

The leader was named.

Elizabeth Brennan.

Steam press operator. Eight years at the Hartley Garment Company.

Thomas felt the room tilt slightly.

The Hartley records confirmed it.

Elizabeth Brennan: injured repeatedly. Docked wages. Listed as a strike organizer.

Next to her name, in blunt handwriting: Blacklisted. Do not rehire.

Her husband, James Brennan, a floor foreman, resigned days after her dismissal.

Thomas imagined the moment.

James standing in a manager’s office. A choice offered without kindness.

Your job, or your wife.

He chose her.

The climax of the story arrived not in violence, but in that choice.

And in what came next.

Because despite being unemployed, blacklisted, and responsible for three children, the Brennans did something extraordinary.

They paid for a formal portrait.

Thomas found Elizabeth’s great-granddaughter, Patricia Hughes, living just outside the city.

When she saw the photograph, tears welled.

“She insisted on it,” Patricia said. “Right after the strike failed.”

“Why?” Thomas asked.

“Because she knew they wanted to erase her,” Patricia replied. “So she made evidence.”

Patricia opened a worn leather box and placed a small notebook on the table.

Elizabeth’s handwriting filled the pages. Lists of names. Injuries. Demands.

Ten-hour workdays. Safe equipment. No child labor.

Decades ahead of the law.

“She wanted future generations to know,” Patricia said. “Not just that she suffered, but that she stood up.”

Six months later, the portrait hung at the Philadelphia Workers History Museum.

Visitors stopped.

They leaned in.

They stared at the hand.

A young girl asked her mother, “Why didn’t she hide her scars?”

Her mother smiled gently. “Because she wasn’t ashamed. She was proud.”

Thomas stood back, watching.

The photograph had done what Elizabeth intended.

It refused to let her vanish.

Her scars were no longer silent.

They spoke.

And history, at last, listened.

News

Susannah Turner was eight years old when her family sharecropping debt got so bad that her father had no choice

The Lint That Never Left Her Hair Susannah Turner learned the sound of machines before she learned the sound of…

The Gruesome Case of the Brothers Who Served More Than Soup to Travelers

The autumn wind came early to Boone County in 1867, slipping down the Appalachian ridges like a warning no one…

The Widow’s Sunday Soup for the Miners — The Pot Was Free, but Every Bowl Came with a Macabre …

On the first Sunday of November 1923, the fog came down into Beckley Hollow like a living thing. It slid…

How One Factory Girl’s Idea Tripled Ammunition Output and Saved Entire WWII Offensives

How One Factory Girl’s Idea Helped Turn the Tide of War 1 At 7:10 a.m., the Lake City Ordnance Plant…

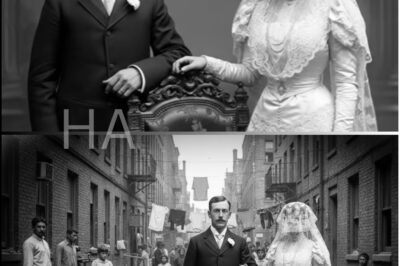

1904 portrait resurfaces — and historians pale as they enlarge the image of the bride

The Veil That Remembered The box arrived without ceremony. It was late afternoon in New Orleans, the kind of slow,…

The Barber Who Used Typhus-Infected Towels to Contaminate the German High Command

The Warm Towel Warsaw, Winter 1943 Snow had been falling since dawn, the kind that erased footprints within minutes, as…

End of content

No more pages to load