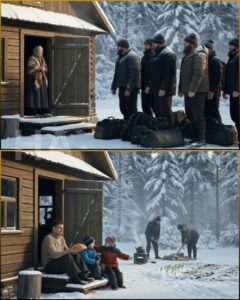

They came in columns, not without order but not with parade precision either; boots punched the snow in steady measure. Hundreds—no, it could have been thousands if the eye could not account for the other edges—filed past, broad-shouldered and focused, faces set against wind, scarves pulled tight. For a second she thought it might be soldiers, a militia marching to a distant warrant. But when their leader stepped forward, when a man with a voice like a bell and the air of someone who had known loss as well as he had known triumph placed his hand over his chest and spoke with a warmth that surprised her, she recognized something different.

“You sheltered our brothers,” he said simply. “We will never forget this kindness.”

The men worked around the house with the delicate clumsiness of those who had only ever used their hands to lift weight, not to hold nests. They cleared the roof, hauled away the broken fence, unblocked the path with a will that was almost gentle. They replaced shingles in the way a concert pianist might replace broken strings: with a tenderness that suggested muscle memory had been married to long-forgotten grace.

One of the senior wrestlers unfolded a chest from his coat. Inside lay tools—actual tools, sharpened and clean—and provisions: tins of stew, dried fruit, a thick wool blanket she’d feel comfortable wrapping around two people at once. They stacked wood by the door until the house, once fragile like an aging heartbeat, bristled with proof against winter.

“I told you,” the captain said, watching them, a small proud tremor in his voice. “If they decide to come, nothing stops them.”

Maria watched them move and felt an unfamiliar fervor of gratitude tighten her throat. She was a woman who had been small in a world growing large and quick and indifferent. She had kept her house because she had to, because habit can be as fierce as need. But standing there in the doorway as men with the power to break entire things bore down to save the smallness of her house, she trembled with something like holy bewilderment.

When their leader approached her again he unfolded a strip of cloth with careful ceremony. Wrapped within was a championship belt that glinted gold in the pallid morning light. It was heavy and ornate, layered with names she could not read but that held the weight of history.

“This,” he said, voice low, “is our highest symbol of respect. Only a few have ever been given one without stepping into the ring. You saved twenty of ours. You protected family. From today, you are one of us.”

Maria laughed, at first incredulous, then wet in the eyes. “For what? For opening a door?”

“For opening your home,” he corrected. “For not asking names before you gave them shelter. For remembering that a person is always more important than the weather.”

The belt was placed around her shoulders with an awkward reverence. It hung heavy, not just in the metallic sense but with meaning. For the first time in years, Maria felt the weight of being seen.

What came next was not the end of the story; it was a beginning that looked like hard work. The wrestlers did not merely repair the house. They set up a small tent of sorts, arranged a schedule to check on the road each day, and promised to send a crew in every morning to clear snow until the thaw. They left behind an insulated thermos and enough food to carry Maria through several storms. They taught her how to send a radio signal with an old battery they had tinkered into life. And when she hesitated about accepting more help—meek, embarrassed—they insisted with a tenderness that disarmed her.

“You’d have done the same,” the captain told her as he shouldered his pack to leave, “if you could.”

“I would have,” she said, because it was true. “Only—only I forgot how to ask.”

“You don’t have to ask to be taken care of,” he said, surprising her with the simple wisdom. “Sometimes letting people help you is the bravest thing you can do.”

The months that followed through the teeth of winter were an odd kind of marriage for Maria and the men who had become her family. Their rigors were different—their working hours, their injuries, the sudden flares of temper that came with old scars—but their presence bound the valley into a new fabric. They would come not always in huge numbers but in pairs and threes, bringing soup or a radio, staying to hear a story in exchange for a laugh. On quiet afternoons some of the senior wrestlers sat with Maria and mended what little needed mending. A young man named Isaac took to sweeping her porch because the action steadied his hands, and because in doing so he could talk about nothing at all and the silence would be company.

It was not all easy. There were bruises of memory that lingered. A man named Rui—a short, barrel-shouldered fellow who had been close to Maria’s son in some unseen way—sat on the porch one afternoon and admitted a truth that made Maria’s chest split wide.

“We did things,” he said, voice thin. “We made choices that hurt people. Not in the ring, but out of it. The world we’re in can be ugly. Some of us haven’t always been proud of what we have done.”

Maria listened until the words sat like cold stones between them. She had ghosts of her own—years when her son had gone away for reasons she had not entirely understood, leaving little notes she unfolded and folded back into the same habit every time. She had known anger, and she had known how it pooled in people like oil.

“You still came,” she said finally to Rui. “Even if you’ve done wrong, you still came to us.”

Rui’s face folded. “I wanted to make something right,” he said. “I don’t know if a stove and a new roof can do that, but it’s a start.”

“And starts are everything sometimes,” Maria said. It was a truth she’d learned in the quiet years, that beginnings could be quiet affairs: a bowl, a belt, a promise.

Word of the rescue spread slowly at first and then with the insistence of a rumor that felt like truth. The team’s leader, a man named Alonzo, arranged for Maria’s house to be listed as a small respite on travel routes. He and the elders used their influence within the circuit to direct aid and supplies across a number of villages that had been forgotten by delivery trucks and local councils. The belt that had hung around Maria’s shoulders was displayed on the mantle between her husband’s photograph and her son’s—an heirloom of a different sort, not taken but given: a reminder that even the smallest actions can carry enormous return.

There were nights when Maria still woke with the old loneliness pricking through, a pocket of yearning that no amount of company could fully fill. But the house no longer felt like a mausoleum for what had been. It held laughter and grumbling youth and the strong aroma of stew and the click and whirr of radios tuned to distant frequencies. The wrestlers came back in groups, bringing a kettle they’d used for competitions to repay the one she’d lent them without wanting it, bringing a bag of shampoos for her hair that had not felt soft in years.

And slowly—so slowly that sometimes she couldn’t tell the difference day-to-day—Maria began to feel like she belonged to a world again, not as spectator but as participant. Children from nearby houses, whose parents were friends with the wrestlers, began to visit and play in the warmed shadow of the porch. On long winter evenings when the sky was hard and the valley was deep in snow, those children would sit around the fire and listen to the older men tell stories about traveling and about the rituals of training and about the time a wrestler had accidentally mistaken a loaf of bread for a training weight.

One spring, when the snow melted and the rivulets freed themselves into the river, the captain brought a package to Maria that managed to bury every other gift in his face. It was a letter, crisp and neat, with a handwriting she recognized before her eyes finished each line. It was written in a careful, direct hand, a hand that had been careful once and then lost its way, and now had found it again.

It read: Mother, I am sorry for all the times I left without saying where I was going. I have done things I am not proud of. But the men I travel with now have been kind to me, and they have taught me to be kind to others. I think of you every time I climb into a van or wrestle in a ring. I know you keep my boots by the door. I am ashamed of that, but I wanted you to have something of me to remember. If you can, forgive me, and if you cannot, I will wait.

There was a small dried flower pressed within the pages—one Maria had given to the boy forty years ago before he left on a day she remembered only in fragments. Her hands shook as she read the letter. The name signed at the bottom was his: Daniel.

She read it twice, then a third time until the words blurred into a trembling, beautiful whole. It was not closure in the grand sense—Daniel’s presence did not return as a person at her doorstep—but it was as close to reconciliation as reality sometimes offers: the acknowledgement that a life had stumbled, that someone had found a way to look back and to say what needed saying.

The championship belt remained on her mantle, but it meant more than that day by day; it was a symbol of the community that no longer saw her as a woman whose days were counted by the couple of boots beside the door. It meant that charity had been paid forward in ways that multiplied and that kindness could be a currency.

Not all the wrestlers were saints. There was arguable history there, the kind of history that sat sour and hard like undissolved sugar on the tongue. But the changes that came were gradual and real. There were stories of reparation: a man who, after tending Maria’s garden, wrote to an old neighbor to apologize for a youth’s mistake; a pair of brothers who used their prize money to improve a schoolhouse that had leaked for years. It was not grand penance—just a series of small, attentive acts that rewove lives together.

One evening years later, Maria sat by the fire and watched a new group of young faces arrive at her door. They were not wrestlers, but neighbors: a young couple pushing a stroller, a teacher with two children in tow, an old friend from the next valley over. They had come with a cake and candles and a chorus of voices that proved how much one person could mean to a community.

“Why are you doing this?” she asked the captain—older now, his hair salted with gray—when he led the song. He smiled in a way that let the valley see the years of travel across his face.

“You opened a door,” he said. “We opened a few in return. You taught us that a house is more than a shelter; it’s a place where people can learn to be brave.”

Later that night Maria fiddled with the belt on the mantle. It had a new name engraved that spring, by careful request from a man who had been senior in the organization for decades: “Maria Hail—Friend of the Brotherhood.” It was a title she had not sought but one she wore like a warm shawl. She thought of the boy whose handwriting had returned to her in ink and dry petals, of the wrestlers who still phoned sometimes to check if she had enough tea, and of the thousand tiny warmthes—discrete, generous—that had stitched themselves into her life.

On the last day of winter, two small boys sat on her porch and argued about whether the earth really had magic in it or whether it was just old, tired hands making the magic. Maria watched them, and then she called Isaac over. He came with the ease of someone who belongs.

“Would you like some bread?” she asked.

He grinned, young and a little ridiculous for a man still possessed of that tender adolescent awkwardness. “Only if you promise not to use it as a weight in training.”

They laughed, and the sound followed the children down the road, and the house—once merely a place to store the leftovers of a life—glowed with the busy, cozy light of a home with more than one life in it.

People asked Maria sometimes if she had ever regretted opening the door that night in the storm. The question, they meant it as a challenge—was she aware of risk? Had she grown careless in old age? The answer that came back was always the same.

“I was cold,” she said. “And they were cold. If you can warm another person, even a stranger, you must. That’s how a life makes sense.”

She never did wrestle in a ring. She had no inclination for combat and rarely any need to lift more than a kettle. She did not wear the belt outside of the house, though sometimes she would take it down and set it across her knees and imagine the weight of it was the weight of lives she had touched and lives that had touched hers in return.

Years glide like a river that your feet can no longer stand upon. They carry some things away and leave other things thoughtfully behind. Maria’s hair grew white, and the house required constant negotiation with the weather and the rot and the world. Yet when the spring sun came at last, it hit the roof with a brightness that felt like forgiveness, and the valley around it stirred like a field answering rain.

On the day she would not be able to keep the fire burning alone any longer, the community would gather and argue about who would take the stove, and who would keep her boots by the door. But that was a concern of another winter. For now, she tended her garden with hands that had not lost the tenderness needed to coax life out of soil. She asked about wrestling matches sometimes, not because she cared about glory but because the men—her sons, she sometimes thought with a small, rebellious smile—sent back stories that were often about ordinary kindness in extraordinary places.

If the curve of the story asks for the place where the beat grows loud, that day had been the morning when they came down the road. It had been a quiet miracle: a small woman and twenty exhausted athletes held the seam of a valley together for a night, and the rest of the world—if the world could be said to take notice—then folded into their presence like a chorus joining a single voice.

Maria’s life had been a string of small, sovereign acts: to boil water, to patch a roof, to remember names. In exchange, the wrestlers had given her a roof repaired by hands that could have shattered walls; a belt that carried names of glory; a family that showed up when the wind put a question mark against the door. She taught them how to let kindness be as simple as a bowl, and they taught her that every kindness creates a pattern that other hands can follow.

On cold, quiet nights she kept the belt on the mantle next to the photographs and looked at it like one looks at a map—less for directions and more to trace the paths taken. When children from the valley grew into the sort of tall boys who might one day join a team, they came to Maria for a story about the night it all began. She would tell them about the storm and about boots and about a knock on the door that changed everything. They would always ask the same question at the end: “Did you ever think they might harm you?”

She would think of the tremble that had first tightened in her chest and of the soup and of the scar over Tomas’s eyebrow and the kindness in his voice, and she would answer simply.

“No,” she would say. “Because when someone needs help, you help. That is the rule.”

When she finally died, the valley held a funeral like a celebration—an arrangement of life rather than a closing off. There were men in heavy coats and children with sticky fingers; there were neighbors and wrestlers and teachers and the small, faithful people who had passed by Maria’s house for years, who had come in for tea and left with their pockets full of something they could not name but felt like warmth.

They carried her body not in a parade but in a procession so gentle that even the snow seemed to hush. Isaac walked beside the casket, his face stone-still with the kind of anguish that comes when one loses the unassailable. Rui read a passage about second chances, because it spoke true for the work he’d done in his life. Tomas placed his hand on the belt and bowed his head.

When the grave was closed, a voice rose—a small, untrained voice from the crowd, a child’s, perhaps no older than ten. “Did she ever regret it?” the child asked as the shovel rang in the dirt.

“No,” someone answered, and the voice was like wind through branches: steady, unshrill. “She did not.”

They left the village that day carrying more than sorrow. They carried a story, a pattern, an example that kept the hearth warm for anyone who needed it. The belt stayed with the team, its name engravings growing, but Maria’s name remained engraved in a different place: the way the valley treated one another, the way a neighbor knocked when the wind came hard, the way people opened doors because she had once opened hers.

The world, of course, did not stop being cruel in corners. There were winters still to come, storms yet to bite. But somewhere at the edge of the valley a little house with a repaired roof held the memory of a night when twenty freezing men became a hundred men became a community, and the smallest act—opening a door—came to mean something large.

Where people asked what had changed, the only honest answer was simple: someone had chosen to be kind. That choice hung in the valley like the smell of wood smoke and made the road easier to bear.

And, if anyone ever passed the house and wondered whether one person could make a difference, they only had to listen for the quiet: a radio in the window, a kettle singing, two children learning how to whistle into the cold. That was enough to know the truth—that kindness, once let out of a small door, has a way of marching back into the world, like boots in the snow, steady and sure.

News

A Billionaire CEO Saved A Single Dad’s Dying Daughter Just To Get Her Pregnant Then…

“Was it a transaction?” the reporter asked, voice greasy with delight. “It was a desperate man trying to save his…

“Come With Me…” the Ex-Navy SEAL Said — After Seeing the Widow and Her Kids Alone in the Blizzard

Inside the air was slow to warm, but it softened around them, wrapped them the way someone wraps a small…

“Sir, This Painting. I Drew It When I Was 6.” I Told the Gallery Owner. “That’s Impossible,” He Said

Late that night the social worker had come. A thin man—he smiled too much, like a photograph—who said her mother…

The Evil Beneath the Mountain — The Ferrell Sisters’ Breeding Cellar Exposed

Maps like that are thin things; they are only directions until they save your life. When the sheriff and four…

The Mother Who Tested Her Son’s Manhood on His Sisters- Vermont Tradition 1856

“Rats in the walls,” she said. “Old house. Winter gets ‘em.” He did not press her. He smiled, mounted his…

🌟 MARY’S LAMB: A STORY THAT CHANGED THE WORLD

CHAPTER III — THE SCHOOLHOUSE SURPRISE Spring arrived, carrying with it laughter, chores, and lessons at the small red schoolhouse…

End of content

No more pages to load