The cases Elena would compile over the next year looked like fragments of a broken glass: each shard cut in a different place but together they made the outline of something larger. There was Bethany, discovered at five years old in a filthy McKenzie house in Kentucky, curled on a mattress, a child with a spine exposed to the world and a body that could not feel the warmth of stability. There was Marcus, locked in a tool shed in East Texas, a child born from the worst of a family’s secrets and the consequence of a man’s criminal choices. There were the twins from New Harmony Colony on the North Dakota plains, Rebecca and Alyssa — one kept, one hidden away until the state’s inspectors pried open an old, lying file.

She wrote about them with a reporter’s carefulness and an activist’s fatigue. People who read the first long piece online told her, in comments and emails and sometimes in small, fragile messages sent through friends of friends, that they had thought the stories were distant, almost medieval — abuses that belonged to a past America rather than a living one. Others wrote with anger: why had the county failed? Why had generations tolerated these unions? Why had experts — doctors, social service workers, clergy — let this happen?

Elena began to answer those questions the way any person who had not grown up in isolation might answer: with a map of geography and history and poverty. Small towns like Odd were the product of dwindling opportunities and a sturdy, stubborn suspicion of outsiders. Where men’s wages had once been enough for a family, the coal had gone and the mills had closed and the county lines felt like borders. Traditions calcified. In places where people stayed and intermarried for generations, recessive genes found partners and amplified each other. That was genetics. The rest — the neglect, the secrecy, the abuse — was political.

“You’re making it sound like a natural disaster,” said Claire Jensen, the adoptive mother who had taken Bethany in. She was small and fierce, and when Elena visited her house in Louisville, Claire had the quiet of someone who had loved a child through rooms of hospital smells and teaching clinics.

“It’s a convergence,” Elena said. “Biology and isolation and failure of the system.”

Claire’s jaw tightened. “And what about the community? Where were the neighbors?”

“They were there,” Elena admitted. “They brought food scraps sometimes. They didn’t ask questions. Fear has ways of speaking louder than courage.”

Claire said nothing further. She had fed and bathed and read to Bethany in ways that made the child’s chest rise with a new, fragile rhythm. She had sat in emergency rooms and had listened to doctors use words like hope and prognosis like the two ends of a rope.

“You know,” Claire told Elena later, “some of our victories are tiny.” She had been the one to teach Bethany sign-language gestures that would let her point to a glass of water or a favored chair. The gestures were brutal in their simplicity, but they meant the child could ask to be picked up without shrieking like an animal. “We get mornings like that,” Claire said. “Mornings with a smile. I keep those.”

It was clear in each case, no matter the clinical names attached to the children, that human beings had two choices: see and act, or turn away. Too often, the nation had turned away.

Marcus’s case had the sweep of a tragedy written by a prosecutor. The man arrested — Robert Earl Thompson — stood in court with the exhausted arrogance of someone who had constructed his identity in the vacuum of his own rules. The files said he had forbidden his daughters to go to school, had chained whole afternoons to the isolation of a family property where the wind scoured the land. He had fathered multiple children by his daughters. He had been sheltered by silence until one neighbor could no longer hold the knowledge.

Elena sat at a back bench during the trial and watched the faces in the gallery: old women with hands like parchment; a neighbor with a jaw like stone; the teenagers who had kept their distance all their lives; and in the middle of it, Robert Earl’s daughters, their mouths set in lines designed to keep things inside.

“Did you feel you had any choice?” Elena asked one of them after the verdict, when the courtroom emptied and coffee had gone cold. Her question was gentle because the answer, when it came, was a list of what protection meant in a place where protection had been forbidden.

“We did not know what the world was,” the daughter said. “We did not know what the laws were. He said the outside is full of devils. He said to keep the house pure. That’s what he used to say. We thought love meant obedience.”

Her voice was flat in the way that limits us all. She had learned to protect what was inside her because the outside had been punishments and the inside had been survival.

The small victories in court were blunt things: one man jailed; some registration papers pulled into sunlight; a child taken gently by someone who had learned — over the months of treatment and therapy — how to coax an infant’s mind toward recognition. Marcus never left the children’s clinic — his brain had been too damaged by repeated trauma and by the genetic toll of those forced unions. He learned, slowly and with great patience, to look at faces and respond. The staff placed pictures on the walls of things he couldn’t have: ducks, a bicycle, a hospital badge. He reached for them sometimes, and the hands that fed him answered with the best care science and empathy could provide.

Not every discovery led to a courtroom. Sometimes the state intervened with the cold efficiency of a machine that had been created to fix human error, and sometimes the same machine missed things. In North Dakota, the New Harmony Colony had insulated itself with a theology that became law inside the family compound. Leah Miller — a social worker who had always been the type to let her heart bruise — had been assigned to inspect home schooling in the colony and had found a file with two birth certificates and only one child presented.

“She said the second child had died,” Leah remembered, tapping a pen against the pile of paper. “But there were gaps. Things that didn’t add up. When we found Alyssa, she was malnourished and hidden in a back room. They had a way of calling it sanctity when really it was neglect.”

Alyssa had already been robbed of surgical windows that might have changed the trajectory of her life. Once a condition like Fraser syndrome becomes advanced, some corrective operations lose meaning. Where a pediatric surgeon might have opened an eyelid and given a child a chance to learn to see, years without care had created damage not easily undone. Still, the doctors at Minneapolis Children’s took her into their care with an unblinking resolve that felt like mercy.

“You can’t unmake what nature and ignorance have conspired to do,” Dr. James Peterson said the day Elena visited the hospital. He had small, kind hands and the militant calm of someone trying to save a life as if law and culture had nothing to do with it. “But you can make a life bearable.”

That was the task set before Claire Jensen and the rest of the caregivers: to make lives bearable when the world had been unreasonably cruel. For Alyssa, surgeries reduced respiratory infections and allowed caregivers to position her head more easily, to wash behind small ears that never fully developed. For Rebecca — the girl who had been raised in the colony under supervision — school became the place where a future opened. She learned math and the names of birds and how not to be terrified when a stranger smiled. She would visit Alyssa sometimes, but the sight of her twin sister became a compass needle for the rest of her life: a conversation she would carry with her between the sticky compartments of grief and responsibility.

Elena kept a recorder in her coat and a pen in her pocket. When she interviewed the social workers who had pulled children into ambulances and into the arms of the state, she found professionals who had spent their careers chasing after the consequences of poverty and secrecy.

“You can have policies in place,” Leah told her over cold coffee and a stale donut, “and still courts and budgets and local politics will hamstring you. One inspector can’t change a county’s culture. One judge can’t make people care. We move the children, and we try to treat them, and sometimes we’re accused of interfering. The truth is — we do the best we can.”

“How do you face days that feel like you’re fighting the same battle on repeat?” Elena asked.

Leah’s eyes narrowed. “You do not let the horror be too big,” she said simply. “You let the horror be a list of tasks: find the doctor, arrange therapy, place the child. You do the paperwork. You write the reports. You sleep when you can.”

Elena would later write that this was the single most damning fact she discovered: there were people who cared and people who had power, and systems that sometimes didn’t connect the two. Funding cuts, religious exemptions, geographic isolation — they all conspired to build a landscape where the worst impulses could breed like mold in damp wood.

She also found a very human fear: people in small towns who worried that once you opened one family’s shutters you would have to open every family’s shutters. Secrets place a ceiling on shame. The moment you let light in, the whole house collapses.

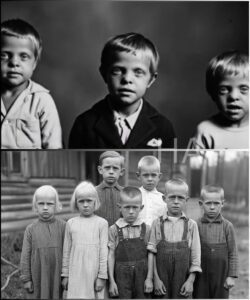

The story took off when Mark Lighter — a documentary photographer who specialized in people left out of the national narrative — released a short film of a porch and a man who could not speak, of a child on a mattress with a spine that had been ignored by medicine for too long. It was a film that forced the country to see things it would rather not have to hold. The comments under the video swung between anger and pity, as if those were the only two languages in which viewers could process the sight of a living human being who had never had a diagnosis.

Soon after, the White House press office received letters, and a senator from the state called a hearing. The images traveled, and so did the outrage. For a while, the national attention acted like a clean rain: people donated money, a nonprofit set up a fund to place children with families trained in medical care, and a small hospital in Louisville opened a clinic specifically to treat the sorts of congenital conditions that had been ignored.

But rain dries. Elena had to remind herself — and the country — that compassion must be transformed into systems to have a lasting effect. Donations could fund a clinic for a year; a change in policy could fund it for a decade. She began to write a second piece not just about the children themselves but about the mechanism that allowed them to fall through the cracks.

In the weeks before the piece ran, Elena received a letter from Betty.

It was written in a careful block print that trembled at the margins. She had signed it “Betty Whitaker” and in small letters at the bottom: “Ray likes his porch. He likes when morning comes.”

Elena read it on the train back to the city and felt a cold, soft knot in her chest that had nothing to do with her heart and everything to do with responsibility.

She called Claire to ask how Bethany was doing. She called Leah to ask about the best legal remedies. She called Dr. Peterson to ask what sorts of early intervention policies could have mattered. She called a state representative and asked bluntly: what are you willing to legislate?

The representative hesitated in the way of someone who knew that politics was economics swaddled in rhetoric. “We can tighten reporting requirements,” he said. “We can fund rural outreach. But be realistic. Budgets are zero-sum sometimes.”

“That’s how children die,” Elena whispered into the phone and was shocked at the fierceness of it.

The piece ran with photographs that made readers look twice. The first comment beneath the headline thanked Elena for the courage of her writing. The fifty-seventh criticized her for stereotyping rural Americans. A long tweet thread broke down the medical terms for readers who had not been taught to think of genetics as more than a meme. A mother in Ohio called to say her cousin had been in a similar situation and that the piece had made her pick up the phone she had been afraid to use for a decade.

Somewhere in the middle of all that, the county sheriff called for a meeting. The sheriff was a barrel of a man with kind eyes and an old bruise on his knuckle from a life spent holding onto things. He wanted to protect his community but could see the cracks forming in the social fabric. He invited leaders — clergy, neighbors, representatives from social services — to a church basement that smelled faintly of lemon oil and old hymnals.

“We can’t change what’s already happened,” he said to the room, “but we can stop another childhood from being wasted.”

It began small. A health van started making rounds on specific days of the month, and a clinic opened in the county seat with a pediatric nurse who came twice a week. A small scholarship fund underwrote the travel costs for parents who promised to take their children to specialists. The largest change came in a quiet policy that required more rigorous follow-up for families where there had been history of cousin marriage when there were signs of developmental delay. It wasn’t perfect. Some families saw it as government overreach. Others — like Betty and Ray’s — accepted the help because they wanted a better life without necessarily knowing how to ask for it.

The New Harmony Colony cracked under the light of inspection. Some families defied the state; some cooperated. Alyssa’s case pushed conversations into the open that the colony had once only whispered about as sin. For Rebecca, who had always been the more robust twin, the state’s intervention meant the possibility of college classes offered online. She learned to read a map and to reckon with the obligations she had inherited.

Marcus’s father received a sentence. The neighbor — the man who had called the hotline — received threats he never reported publicly. Elena understood then how fragile heroism could be: it is not glamorous; it is the act of someone answering a phone at 2 a.m. because something in their guts had been unable to stand the silence.

Not everything could be repaired. Not every operation fulfilled its promise. Bethany would live with paralysis; she would need care for the rest of her life. Marcus would never fully integrate into the life he had been denied. Alyssa would never see. The law could not return infants to mothers who had taught them only obedience to cruelty. But politics did what it could, and a small, dogged coalition of doctors, social workers, and policymakers turned attention into budgets and budgets into clinics and clinics into the possibility for better lives.

Elena’s last visit to Odd was in late autumn, when the trees let the last of their leaves scatter like gold coins. Ray was on the porch, and a nurse from the county clinic sat beside him with a thermos and a sturdy patience that seemed built of the small kindnesses she gave each day. Betty came to the porch with two mugs of coffee. For the first time, there was a small pump for water in the yard, installed by a volunteer group that had organized through a fundraising page.

“You did a good thing,” Betty told Elena and then laughed when the words surprised both of them. “You put our picture in a place that made people see.”

Elena did not say hers was only one voice; she had not done the saving. She had only pushed the door wider. She thought of all the times she had wanted to be bigger in the world, had wanted to be the person who could fix everything with a headline. She was not that person. She was small.

“You were brave,” Ray said in the low, broken language he had. His hand found hers and squeezed, and the gesture meant more than any editor’s byline. It was a human exchange, unmediated by cameras or clicks.

When Elena left, she wrote a final piece that was not an exposé but a letter. It listed the changes made, the clinics opened, the children placed, the policies enacted. It also listed what remained — the children who still needed care, the county that would need sustained funding for years, the families who would fight to keep things as they were. She placed the story at the end of the magazine as a challenge: the impulse to look away had been the original sin. Now, seeing was not enough.

She received mail from survivors who had read it in prison, from a grandmother in Ohio who had hidden a grandchild from social services for fear of losing them, from a nurse who wanted to start a mobile clinic in a neighboring state. The letters arrived like small flags, some bright with gratitude, some tattered from long use.

One night, she received a parcel with no return address. Inside was a small button with a rooster perched on it and the word: REMEMBER. There was also a note — a clumsy hand, a mix between a child’s alphabet and an adult’s attempt to write short sentences: “We are here. We were forgotten. Thank you.”

Elena pressed the button into the fold of her notebook and felt a softness she had not given herself permission to feel: hope. It was not the easy hope of a trending story or a fundraising total. It was a stubborn, less photogenic thing: the hope of people who had been seen and held and whose lives were, in small degrees, less lonely.

Years later, when the lawsuits had settled into the slow drag of appeals and the clinics had a rhythm, Elena returned for a last interview to write a piece that was less about horror and more about the mechanics of compassion. She found Betty on the porch with a sewing machine and a pile of fabric. She had learned to sew in a community program and sold small quilts at the county fair. Ray sat in the sun and watched the world, and when he laughed, it was like a bird calling.

“We planted apple trees,” Betty told her, pointing to a small orchard at the edge of the yard where saplings stood like sentinels. “They’re not big yet, but they will be. We water them every week.”

Elena thought of all the apples that would fall in a decade she might not see. She thought of how fiercely ordinary the farm was now; the lights on the porch bulb were safer, the pump hummed. She thought of the small nurses who took shifts to sit and read to children with syndromes the textbooks barely sketched. She thought of Claire and Leah and Dr. Peterson and the neighbor who had called. She thought of how the country sometimes needed a photographer to show it what it already knew in order to act.

“We had bodies that wouldn’t lie down,” Betty said suddenly, and there was a gravity in her voice that surprised Elena. “We had bodies that had been boxed up, kept quiet. Now we have people who come.”

“You have people who come,” Elena corrected gently.

Betty smiled with a kind of confusion that had nothing to do with lack. “That’s what I meant. People who come.”

The end of the story was not a neat ribbon. There were still bureaucrats who argued. There were still families who refused help. There were still children in clinics who would never walk, never see, never speak in the way some call seeing and speaking. But there were also, now, nurses who understood which signs mattered and judges who would not let an inspector’s voice be the last in a county’s ear. There were clinics that would be part of grant cycles and donors who had pledged sustained support rather than headlines.

On her last night in town Elena sat on the porch with Betty and Ray and listened to the invisible things — the river’s small insistence, the heart’s more private metronome. She thought of a country that had made a place called Odd and then called it ordinary.

“If you had to write one sentence about what changed,” she asked Betty, “what would it be?”

Betty considered. The words came slowly, like someone summoning a memory in a language they had to look at to trust.

“People decided to look,” she said.

Elena closed her notebook. The sentence was not everything. It was the beginning of the story she had been telling: not the story of the children’s deformities and neglect, nor merely the amassing of facts and files and medical lexicons. It was the simple truth that the moral arc of a community is made of what people are willing to see and then do.

She left Odd with the button still in her pocket, the REMEMBER pressed against her heart. In the city, she would put the name Whitaker next to Bethany, next to Marcus, next to Alyssa and Rebecca, and she would not let them be reduced to a series of clinical terms. Each would have a face in the book she would write, a face that bore witness. She would demand the policies that moved from emergency passions into permanent systems.

The story that began as a set of cold clinical notations had become, in the end, a lesson in human decency. The world would still make mistakes. People would still be frightened to look. But somewhere on a porch in a place with a small, mocking name, apples were planted and tended, the pump hummed, and two people whose genetics had once seemed to write a tale of inevitability now lived in the small, stubborn light of being seen.

The light was patient. It lasted.

News

End of content

No more pages to load