Later that night, after hot water and the first tasted fish since long before Michiko could remember, Yuki slipped her small cloth bag away from her waist and left the razor inside the cot. She touched the place where the sharpness had been and laughed—soft and stunned. “They will not hurt us,” she told Michiko.

“Then why are they so kind?” Michiko asked.

“Why would someone offer an enemy soap when they planned to cut them open?” Yuki answered. Her voice was still trembling, but it was steadier than the day before.

“What do you want?” asked Ko, voice threaded with worry. She had been a schoolteacher before the war pulled her into a military office. “Do we trust them? If we accept this care, do we betray our dead?”

That question hung in the air and the barracks hummed with it. Some nights the debate turned to shouting. The older ones—Mrs. Yamada most of all—said kindness was a trap. “They would be fools to show mercy when they could break us,” she insisted. “Shame cannot be washed away with soap.”

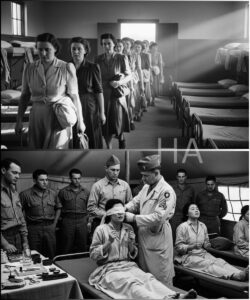

But the more bandage and soup and conversation there was, the more complicated things grew. Fumiko, the trained nurse, watched Americans treat Japanese soldiers with the same concentration she had always thought only her own could offer. Private Tanaka, a boy no older than twenty, lay under clean bandages and wept as he told the nurse he “should have died.” Dr. Chen knelt and met his weeping with a steady hand. “We save people,” she said, and it was not a philosophy so much as a simple profession.

“It is not hatred you would want from them,” Fumiko told the others quietly. “Hatred never brings a healing. It only brings a wound.”

The turning was not immediate, nor total. It took the accumulation of small things: a chocolate bar given in secret to send to a mother; a soldier teaching Michiko how to read a shipping manifest; a radio that played a Japanese folk song; a copied page of the American Declaration of Independence read aloud by a patient sergeant who wanted to explain why his country did some of the things it did. A woman cannot change the world on the strength of a single kindness, but a day after day of them chips away at rigid certainty.

Michiko wrote everything. The notebooks filled: September 20th—“One week in the American camp. They continue to treat us well. I do not understand.” September 27th—“Letter from mother. Father died. Teeshi missing.” October 3rd—“Yuki threw away her razor. Says she does not need it.” October 10th—“I dream of bombs.” The entries became a map of a transformation, not all at once but steadily.

The climax formed like a storm one month after the examinations when the Americans gathered the women in the mess hall to offer them a choice: return to Japan now, or stay and work as paid civilian labor in the camp and beyond. It was framed as a chance—to choose freedom and wages in exchange for helping rebuild, or to go home to ruin and shame. The room split on the question.

Mrs. Yamada—rigid as a set rule—stood up and announced she would go home right then, that she would not live under the employ of the enemy even if it meant survival. Her chest lifted with a belief that still had its claws. “I will not wear their clothes as my dignity,” she said. “Better to be dead than a servant to those who made us this way.”

“You speak as if the only dignity is in death,” Yuki said, voice small, but defiant. “What if dignity is in living? In teaching children to read? In taking care of people when they fall? What then?”

Her question widened like a crack in a dam. For some the dam held. For others, it burst. Michiko felt the stir of everything she had seen—the hospital, Dr. Chen’s hands, Sergeant Mitchell’s wallet picture—and she stood.

“I will go home,” she said, slowly. The hall tasted like sand in her mouth as if the words had grit in them. “But I will go because someone must tell what happened here. Someone must tell our people that what we were taught—that the Americans were demons—was a lie.”

“You will be called a traitor,” Mrs. Yamada snapped.

“Perhaps,” Michiko answered. “But the truth is heavier than shame.”

The decision to go home became the climax because travel allowed the perspective shift to meet its real test. Actions taken in a camp under American oversight were one thing; the civic life of a defeated country was another. The ship that took Michiko and a handful of others carried more than luggage. It carried guilt, new clothes folded to disguise detention, stacks of chocolate and soap in wrapped parcels, and the notebooks that Michiko clutched like sacred things.

At the dock in Kyushu, the country they had left behind looked like a broken promise. Buildings were ragged stumps of themselves, smoke stained the sky as memory blurs itself with ruin. Michiko’s mother waited in a shelter that had once been a school. She was smaller than Michiko had expected, older, the face of a woman who had been carved by grief.

“My daughter,” she sobbed. She dropped and clung to Michiko’s knees. Their embrace was raw and necessary. The sweetness of a soap bar held in Michiko’s hand felt obscene. “Where did you get these?” her mother asked.

Michiko told the truth.

“The Americans,” she said. “They made us wash. They gave us food. They treated us like people. They bandaged my hands. Dr. Chen—she saved Private Tanaka. Sergeant Mitchell—he—”

Her mother’s face changed. The features smoothed; something like ice settled over her eyes. “You accepted gifts from the enemy,” she said. “You accepted their help.” The words were not sharp; they were a verdict.

“I did not accept anything but mercy,” Michiko answered, but her mother would not hear mercy as a thing for her daughter; only shamely consolation for a humbled nation.

The hardest scene in the story unfolded there on a straw mat in a cramped shelter. The mother insisted that Michiko keep silent, that she not speak of the American kindness. “They will call you a collaborator,” she warned. “If you say your enemies were gentle, we will have no story left. If we have no story of sacrifice, who will mourn rightly?”

“What if their kindness mattered more than our poem of suffering?” Michiko asked, an answer that was for herself as much as anyone. “What if what we owe is to the living?”

Her mother’s hands went to Michiko’s cheeks as if to measure whether the child she knew still remained. For a moment time pressed their faces together, two waves moving with different rhythms.

“You are my daughter,” her mother said at last. “You are alive. I cannot punish you for living.”

But the shelter would not forgive easily. Rumors spread—about women who had been soft on the Americans, about the chocolate and the soap that smelled of betrayal. In a small market near the temple, some men spat at the sight of American uniforms and at any Japanese who spoke too kindly of them. Sato’s mother-in-law refused to speak to her; Mrs. Yamada glared in the street as if force could purge an internal heresy. Rumors are sharp; they cut where swords cannot.

Michiko kept writing. She wrote in cafes, which were more like rubble behind a tarp now, as she traveled to other cities to meet people. She tried to tell the story; it was simple and complicated at once. “They saved our hands,” she would say. “They gave us soap. We were not experiments. We were not monsters. They were people who did not want to kill us when they could.”

Sometimes people listened, and the listening was its own small kind of redemption. Older veterans who had lost sons and husbands stepped forward and said quietly maybe the world could change if they learned not only how to fight but how to forgive and also to be helped without seeing it as betrayal. At other times they spat curses because the narrative of suffering was the only anchor they had; admitting a better treatment would unsettle meaning itself.

The narrative tension pushed Michiko into public life in a way she had never imagined. She stayed in town long enough to get a piece printed in a recovered regional newspaper; a short letter where she recounted the name of the doctor who had bandaged her hands, the smell of the soap, the way an American soldier had taught her to label a crate. The letter outraged some and consoled others. She received a postcard in the handwriting of Sergeant Mitchell that said Keep going. Tell it as you saw it. That tiny note reassured her that small acts could carry cross-cultural weight.

A single scene became the crux of her moral test a year later when a small group petitioned to keep Fumiko as a nurse in a local hospital run now by an occupying authority and Japanese staff working under supervision. There was resistance. Residents called to block the decision; they shouted that she was “too close” to the Americans, that her “softness” would ruin the solidity of a wounded nation. Michiko stood before the crowd in the cold dawn and spoke.

“I was treated with kindness,” she said into the microphone that fuzzed and hummed. “I saw Fumiko in the hospital there, and she made me see that humanity is not a national thing. She saved a boy and told him he deserved to live. Do you want us to be better or do you want us to be the same?”

A murmur ran through the crowd and the old stories rustled like dry leaves. Then Mrs. Yamada rose at the very back with arms folded. “We must not forget who we are,” she said. “We must remember what we lost.”

Michiko sat down because she had nothing to say that would unmake loss. But the petition passed, narrowly, and Fumiko remained. She would nurse countless boys whose fathers’ voices had fallen silent in the bombing raids. Each life sewn back to the world felt like a counterweight to the thousand ways the country could have remained mired in pure grief.

Time did not heal everything. Some wounds remained raw: families who wanted their daughters not to return if they had been prisoners; men who could not accept the humiliation of occupation; old women who insisted that survival without ritual death was meaningless. But seeds were planted too—schools reopened, and in one of them Michiko taught.

She taught history because she believed truth was the only good armor. The truth was complicated. She read from her notebooks in class and asked the children to draw maps of kindness. She taught them about the weeks in the tents, the smell of antiseptic, the ribbon the sergeant had braided into her hair. “Why does it matter that they washed us?” a child once asked. “Because,” she said, “washing makes room for thinking. Dirt makes you forget that others are people.” The class laughed, because children always know how to be precisely honest about strange things.

Years later, when Michiko’s own daughter—soft and curious with her mother’s dark eyes—asked about the story of the soaps and the bandages, she told it plainly.

“It was the hardest thing I ever learned,” she said. “I learned that everything I had been taught could be wrong. I learned that humiliation can be replaced with compassion, but not without a cost. You must be brave enough to tell the truth even when it hurts people who have already suffered.”

Her daughter looked at her as if measuring the weight of those words with hands that had not yet learned to hold grief. “Do you think the men who spat at the Americans ever forgave you?” she asked.

“I do not know,” Michiko said. “Some never did. But others did. The men who spat were not only angry at me. They were angry at the loss of their sons, their homes, their whole world. That anger needed a place to go and if it was not given its own history, it would find a scapegoat. That is why telling both truths matters—the truth of loss and the truth of mercy.”

And so the story that began with a whispered instruction to close their eyes became, in Michiko’s notebooks and in the hush of schoolrooms and the odd letter in a soldier’s handwriting, an argument that the world could be otherwise. It was not a tidy redemption. People in the village still complained, and some families never spoke to their daughters who had been prisoners. Mrs. Yamada remained unbending for a long while; she argued that the emperor’s way was right because it had given them a meaning that survived calamity. In the quiet of a late autumn when the rice had been thresh and the wind had turned, Michiko found her sitting on the steps of the temple alone.

“I did not come to forgive you,” Mrs. Yamada said when Michiko approached. She looked smaller somehow. “But I came because I could not stay angry forever. The years have done something I would not have expected: they made me tired.”

“You cannot be reconciled with a nation by yourself,” Michiko said.

“I am not reconciled with the concept of being conquered,” Mrs. Yamada continued. “But I can be reconciled with my neighbor.”

They did not reconcile neatly. There was a silence of hours. Then Mrs. Yamada reached out and touched the notebook Michiko carried—the spiral dented from years of pages. “You kept writing,” she said. It was a statement of fact, small as a pebble.

“I kept writing because truth must be held,” Michiko answered. “And because someone once gave me a chocolate bar to send to my mother.”

Mrs. Yamada’s mouth drew. “Chocolate? How embarrassing.”

Michiko laughed—a small, tired sound like someone testing a borrowed lung. “It was embarrassing and holy.”

And that was the human end Michiko wanted: not a neat forgiveness where everything becomes new, but the acceptance that the world makes room to be multiple. The Americans had not been angels who erased all guilt; they were people who, in one corner of the world torn apart, chose mercy when they could have chosen spectacle. The Japanese women who survived carried the knowledge like a shard into their futures: it would cut and then heal. Some would be branded as traitors for speaking of kindness. Others would teach the next generation not how to kill for glory but how to bandage a wound. The nation that had once taught its children to see the enemy as less than human had been forced to relearn that the definition of humanity is broader than any flag.

Near the end of her life, Michiko returned to the sea where the ship had taken them back to Japan. She stared out over the same grey water; the horizon was unchanged, a thin line where sky met sea. The waves were the same old thing that had always carried people away and brought them home. She thought of the words they had told each other in the tent—Close your eyes and don’t scream—and she felt the phrase fold into a new sentence.

“Open your eyes and see clearly,” she wrote in her last notebook entry. The words were simple, their power not in their poetry but in their stubborn insistence.

She had been given a gift in the barracks and in the hospital and from a soldier who showed her his daughter’s graduation photo. The gift was the proof that you can be brutal and still be human; you can conquer and still choose mercy. The hardest lesson was not the discovery of American kindness. It was the willingness to carry the truth back home and to trust it would find a place.

Her students learned a history that had both shame and comfort. They learned that the world had cost them dearly and that they had choices in what to keep and what to leave behind. They learned to wash their hands with care and to speak to the wounded without the old gods of glory watching over them.

The thirty-two women—the ones who had stood in the morning heat and told one another to close their eyes and not scream—lived out their lives in many ways. Some stayed on Okinawa to help rebuild. Some returned to mainland towns and found new homes among the ruins. Mrs. Yamada never fully surrendered her belief in ritual, but she softened in ways that counted; Fumiko—the nurse who had chosen to stay—nursed countless men who returned from the brink. Yuki married a quiet carpenter and planted a small garden, and sometimes she would catch the smell of lavender soap and close her eyes to remember the day she discarded a razor and chose living.

In the end, the story was not about who had been cruel and who had been kind in absolute terms. It was about the small human acts that shift the axis of a life: a bandage applied with care, a photograph shared across languages, a soldier who hands a bar of chocolate with a stammering apology for its smallness. The war had taught blood and ideology, and it taught pain that never entirely goes away. But the aftermath taught something more dangerous and more valuable: that mercy is a form of power, that kindness breaks armor, that the hardest duty may be to tell the truth even when it shames you and those you love.

Michiko’s last lectures were not triumphant. They were quiet gatherings at dusk when the students brought rice to share and an old radio played a song about cherry blossoms. They spoke of how to build schools and hospitals and how to treat a neighbor whose face carries the same grief. She taught them to write in notebooks like the ones she had kept—small, stained, honest—and to keep those records safe.

“Write what you see,” she told them. “Not to please the winners, and not to flatter the dead, but because truth is the only way we will make sure we do not repeat what we have done.”

When she finally closed her own notebook for the last time, a young teacher came with a box from a soldier in Ohio whose daughter had married a Japanese schoolteacher. Inside were a photograph and a letter and a packet of pencils. Michiko placed them on the classroom altar: a photograph of a man smiling in caps and robes, a note that said Keep going, and three pencils, sharpened and waiting.

She had come back from the war with wounds, with debt and memory and a ledger of loss, but also with an argument for a life that did not hold revenge as currency. Close your eyes and don’t scream—had been the fearful whisper that raised a city of women ready for ritual death. Open your eyes and see clearly—became the instruction that turned survivors into witnesses.

If someone asked her why she had gone home with that story, why she had faced mothers who spat and children who asked small impossible things, she would have said simply: “Because somebody had to tell it. Because mercy is a crime only to those who need to hold their sense of meaning together with lies.”

In the end, the notebooks passed from hand to hand: a student who became a journalist, a woman in a village who would read the truth aloud while the rice dried, a child who would teach another child that an enemy is first of all human. The war had taught them how to be cruel; the camp had taught them how to be gentle. The balance of those lessons shaped the small, patient work of rebuilding a country not with slogans but with soap, bandages, and stories written in careful blue ink.

They had been told to close their eyes and not scream. They opened their eyes instead, and they told.

News

The Twins Separated at Auction… When They Reunited, One Was a Mistress

ELI CARTER HARGROVE Beloved Son Beloved. Son. Two words that now tasted like a lie. “What’s your name?” the billionaire…

The Beautiful Slave Who Married Both the Colonel and His Wife – No One at the Plantation Understood

Isaiah held a bucket with wilted carnations like he’d been sent on an errand by someone who didn’t notice winter….

The White Mistress Who Had Her Slave’s Baby… And Stole His Entire Fortune

His eyes were huge. Not just scared. Certain. Elliot’s guard stepped forward. “Hey, kid, this area is—” “Wait.” Elliot’s voice…

The Sick Slave Girl Sold for Two Coins — But Her Final Words Haunted the Plantation Forever

Words. Loved beyond words. Ethan wanted to laugh at the cruelty of it. He had buried his son with words…

In 1847, a Widow Chose Her Tallest Slave for Her Five Daughters… to Create a New Bloodline

Thin as a thread. “Da… ddy…” The billionaire’s face went pale in a way money couldn’t fix. He jerked back…

The master of Mississippi always chose the weakest slave to fight — but that day, he chose wrong

The boy stood a few steps away, half-hidden behind a leaning headstone like it was a shield. He couldn’t have…

End of content

No more pages to load