The first time Arthur Hale came to the cemetery after the funeral, the world had felt manageable—if only because it had a schedule. Sundays were for contrition: a private drive through the neighborhoods he had built, a brief stop at a granite slab with polished bronze, the dropping of wildflowers instead of a monument he could not bear. He was a man of numbers whose loss stubbornly refused to convert into spreadsheets or balance sheets. For five years, the ritual steadied him. The city rose below him—his skyline of glass and ledger entries—but the towers were only trophies. They bought him power, but not a son.

That Sunday there was someone else kneeling by the stone.

Arthur’s Rolls eased to a stop and Robert—his driver of twenty years, the one steady human presence left—said nothing, as he always did. Arthur stepped out, the cuffs of his suit as precise as the world he commanded. He expected, as he always did, the hush of exclusive lawn and wind through oaks. Instead he found a small, stunned figure sitting with her palms pressed to Captain David Hale’s name.

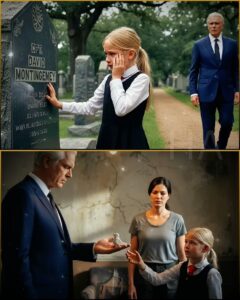

The girl looked like a scrap of a memory: a faded blue dress, thin hair in tangles, the shame of threadbare shoes. She was crying quietly, more trembling than sobbing, palm tracing the letters as if to convince herself they were real. Arthur’s first feeling was irritation—this was private ground, his quiet atonement. Then—because grief has odd instincts that envy tenderness—he waited, watching the child.

She looked up as the sound of his boots disturbed the grass. Her eyes were the same clear, startling blue that David’s had been. They were rimmed with red and wide with a kind of terrified defiance. She leaped up and bolted into the trees, small feet moving like a frightened animal. Arthur called after her; she did not look back.

He found a toy where she’d been sitting: a chipped white wooden bird, the paint worn to bare wood at the edges. He held it for a long time that evening, more rapt than he had ever been over a board report. He ordered Marcus Thorne—private investigator, discreet, efficient—to find the girl and to look up Susan, a former maid who had left the Hale household not long after David’s death.

Marcus called back at dawn. Susan Miller. Apartment 3B. Tenement on the south side. No school records for the child. Emily Miller, age ten. Off the grid.

Arthur dressed like a man preparing for war. The city the car burrowed through was a different currency—brick, soot, boarded windows. He felt the weight of his Rolls like an indictment. Robert protested outside turned streets and dangers. Arthur insisted. He would not hand this to a team. If David had trusted Susan and told her something, Arthur wanted the answers straight.

The stairwell of 3B smelled of damp and decay. The hallway smelled of other people’s lives stacked upon each other. Arthur’s knuckles trembled the moment he rapped on the door; it was the smallest door he’d ever had to knock on and the one that mattered most.

Susan opened it a sliver. The woman he’d once seen in the mansion—silent, efficient—was a ghost now. Her eyes were hollow with exhaustion. She started to pull the door closed but then it opened wider and the child from the cemetery peered out, holding a tattered book. Emily stared at Arthur and fled behind Susan’s skirt, but something about the sight of him softened her grip on the book.

“I saw you at the cemetery,” Arthur said, finding his voice rough. “She dropped this.” He held up the wooden bird. Emily’s face changed; she gasped. “My bird!” she whispered, and in that tiny word an impossible chemistry kicked.

“You don’t belong here,” Susan snapped, more to the girl than to Arthur. “You scared her.”

Arthur pointed at the photograph in Emily’s little backpack—the one Susan clutched like a liturgy. It was a young man in uniform. David. A knowledge heavier than suspicion hit Arthur then: the dates did not match cleanly. Yet the girl’s eyes were undeniably his son’s. She fit a lineage that Arthur had never wanted but always suspected might exist without his permission.

“Is he—” Arthur began, then stopped. The words felt obscene. “Is he—my son’s?”

For a moment there was nothing but a tired, dangerous silence. Then Susan said, in a voice so small it might have been a pretense of sleep, “Yes.”

The declaration landed like a felling tree. The corridor seemed to tilt. Arthur felt dizzy—a man whose life had been built on certainty suddenly undone by the notion that his son had chosen a life hidden from him, that a granddaughter existed and had been kept secret.

“You have no claim on us,” Susan said, slamming the door with the practiced, defensive finality of someone who’d made this maneuver a habit. The deadbolt slid home like a verdict. Arthur, who had never known the sensation of rejection without recourse, found himself with nothing except the urge to add and subtract, to track and to gather. Marcus’s team scoured for them; Arthur’s study became a war room, his life narrowed to a file of letters, a birth certificate, and a whittled wooden bird. He read David’s journal and letters as if could excavate the son he had failed to know. He found entries about a late-night library conversation, a future planned in whispers, the sentence that cut him like ice: “He told me you’d try to own us.”

That line stayed with Arthur the way an accusation lodged under the skin. He paced his study and read the letters until the paper blurred. The military had a DNA test on record—the man had known he would be a father—and yet Arthur had been kept in the dark. Anger and shame contorted together until guilt settled like concrete. He had been cruel. He had been small. He had lost his son twice: once to the desert and once to his own hubris.

When Marcus reported that Susan and Emily had fled the tenement into the night, Arthur felt both rage and fear. He wanted to gather them by force, to use lawyers and affidavits, to secure Emily a trust fund and nurse her without asking so as to make amends out of his ledger. Then he read what David had written about wanting to protect the life he was building—away from his father’s empire—and Arthur realized the only path that might honor his son’s memory was humility, not acquisition.

“We don’t take,” Susan had told him. “You buy things and people become things. David knew that. He said you would try to own us.”

Arthur thought of a man sitting on his son’s bed, reading the journal until his eyes burned. He sat until morning in a chair that once belonged to meetings, and when he finally called Marcus he did so with different instructions. No police. No legal teams. A private check from David’s own trust, no strings attached. The finest family attorney, but not one whose instincts would turn Emily into property. He wanted to find them and offer a hand that could be refused.

They traced a sister: Clara Reeves. Holton, Illinois—small town, old habits. An electric bill spiked the night before; someone had been given a place to sleep. Arthur drove there, the trip a long corridor of cornfields and second thoughts. He walked through the town in an ill-fitting coat that jarred the people who recognized the Rolls parked like an accusation on Main Street. He knocked on Clara’s door.

“Who are you?” a woman’s voice asked, wary as a shotgun’s bark.

“My name is Arthur Hale,” he said. The name was an admission and a penitent prayer rolled into one. “I’m David’s father.”

The reply was immediate and sharp. “You’re the reason they run.”

Susan arrived, thin and in the shadow of a lifetime of evasion. Emily came, sleep-straw in her eyes, pajamas too small for her. When Arthur crouched and held out the white wooden bird the little girl had claimed, she stepped forward, tentative, and took it. Her fingers were small and warm. She looked at him as if trying an equation: the face in the photograph matched the man before her, but this one smelled of coffee and dust, not cologne and cedar.

“I read his letters,” Arthur said, breathless as if holy. “The ones he never sent. He…he was coming home. He wanted to marry you. He wanted to tell me. I—” His voice shredded. He could not finish being the man who had broken a life.

“You would have tried to own us,” Susan said, each syllable a shield and a confession. “I would have given her to you back—and you would have taken her into something else.”

“I would have, five years ago,” Arthur said, the admission like a confession. “Not now. I won’t own anything. Whatever you do with this, I’ll honor it. I’ll help you on your terms.”

Anger warred briefly in Susan’s face with distrust. She picked the envelope laid on the railing—David’s money, Arthur insisted—and eyed it like a venomous thing. “What guarantees do I have?” she asked.

“None,” Arthur answered. “Only my word.” He meant it. That word had been the least reliable currency in his entire life, and yet he offered it without contracts or creditors.

Emily, who had been watching like a small judge, tilted her head. “Why did you come to my daddy’s grave?” she asked.

Arthur knelt so his face was level with hers. Every bone in his knees protested, but he didn’t care.

“I thought I was the only one who could bring flowers,” he said. “I was wrong.”

She smiled. “You cried.”

He did not hide it. He had been crying the entire drive there, later and louder than any confession fits. Emily set the wooden bird on his hand as if bestowing absolution. “Thank you for finding him,” she told him. For the first time in a long while, he believed there was a thing like mercy.

They did not stitch their lives into something seamless overnight. Susan’s caution had been earned in days of hiding and years of distrust. She accepted the money by degrees and the help more guardedly: a night class for nursing school paid for; a small deposit for an apartment in a town where no one would know the name Hale; an account opened with no gag clauses or guardianship imposed. Arthur signed forms and then refused to watch the signatures; he had read too many contracts to imagine one more to heal a wound.

Winter turned and then the next spring found them at Westwood Memorial Gardens again. Emily had a new coat and a shy, proud gait that betrayed the accommodations of safety. She knelt and placed the chipped bird near the bronze plaque. “Hi, Daddy,” she whispered. Arthur stood beside Susan, and they held hands—an unlikely trio beneath a blue sky.

“We can be brave,” Emily said, as if quoting a conversation had taught her bravery. Arthur’s chest constricted and then eased. He had little claim to the word “father” beyond his name, but now he had something else: a granddaughter who would teach him what the ledger could not measure.

The years to follow were small, discrete acts of repair. Arthur learned that humility is not a button to press but a muscle to strengthen. He visited without insistence. He paid for therapy for Susan, and for Emily when nightmares surfaced. He made sure Emily had a piano lesson and a doctor who would not leave a medical chart undone. He halted an acquisition to attend a parent-teacher night. He renovated, quietly, a house in a neighborhood no one in his circles made fun of; it was modest, with paint colors that mattered to no one but the child who chose them.

Equally, Susan taught him how to be useful without being controlling. She would not be bought by a man who had been cruel. Trust had to be built in moments: shared dinners rather than remittances; Arthur carrying groceries without a ledger, Emily teaching him to water a plant; Susan showing him the bruises raw from a past life were not stickers to fix, but maps to navigate. David’s memory threaded through everything—his journal displayed in a simple frame in the new kitchen, his picture honored by a quiet family ritual—David had been both a son and a man who chose love the way an exiled captain chooses land.

There were setbacks. Susan would withdraw when Arthur made a gesture that smacked of grandiosity. Arthur would flinch when asked to do simpler things, like push Emily on a swing, because sometimes doing nothing had been his loudest cruelty. But the loop tightened differently: apologies were given and accepted; mistakes were made and repaired. The man who had once believed control was a kind of safety learned the opposite: safety sometimes looked like letting a child choose a scarf.

On a mid-October Sunday, Arthur walked the cemetery with Emily’s hand in his. He put a small wooden bird on the stone, now less chipped, and he whispered something David never heard—an apology and a promise folded into one breath.

“You found us,” Susan said later, not as an accusation but as an acknowledgment. “You didn’t take her.”

“No,” Arthur replied. “I didn’t take her. I only wanted to be with her.”

Emily, perched on a stoop that had once belonged to strangers, slid her hand into Arthur’s. “You’re okay now,” she said—simple, childlike, infallible. Arthur looked at the city skyline in the distance. The towers still bore his name, but they had shrunk to mere background. In front of him were a woman who had survived and a girl who carried his son’s eyes.

He had built empires, but the richest thing he had ever held was a small hand. Arthur had lost a son and discovered a granddaughter in the same stroke of fate. The discovery unspooled his arrogance, but it rewove him into something else: a grandfather learning how to love without buying, a man whose accounts finally balanced in a way money never could. The world was not tidy, and the grief was not gone. But there was a continuity now: a wooden bird on a grave, a kitchen where laughter happened when it could, the quiet hum of a life more carefully lived.

News

BUMPY JOHNSON’s Betrayer Thought He Escaped for 11 Years — Then the Razor Came Out at Table 7

Bumpy liked that. Harlem ran on reputation, but empires ran on discipline. So Bumpy took him under his wing. He…

“I only came to return this thing I found…” The manager laughed, but the owner was watching everything from the window.

Lucas Ferreira clutched a yellow envelope to his chest as he pushed open the building’s glass door. His hands were…

She Was Fired at the Café on Christmas Eve—Then a Single Dad at the Corner Table Stood Up…

“Jenna called out again,” he said, as if this was news. As if Claire hadn’t been running Jenna’s section since…

Poor deaf girl signed to a single dad ‘he won’t stop following me’— what he did shock everyone

She wrote: A MAN IS FOLLOWING ME. I AM DEAF. I NEED HELP. A desk officer tried. She could see…

“Mister… Can you fix my toy It was our last gift from Dad.”—A Girl Told the Millionaire at the Cafe

A little girl stood a few feet from his table, clutching something tight to her chest. She couldn’t have been…

Sad Elderly Billionaire Alone on Christmas Eve, Until a Single Dad and His Daughter Walk In…

Robert would order the lobster thermidor, always, and a bottle of 1978 Château Margaux, always, and he would take her…

End of content

No more pages to load