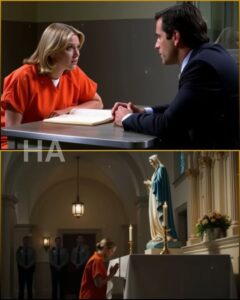

They spoke about the things people speak about to keep time moving—school, a new dog, the guitar lessons Emily was taking—and their talk stitched for twenty minutes a world in which mothers graduate from prison. When visitation ended, Emily stepped forward with a hesitant hope and asked, “Can I hug you?”

Jennifer nodded. They held one another in a hug that felt like the only currency left between them. “I love you, Mom,” Emily breathed against her ear.

“I love you too,” Jennifer said, and for the first time in years, the word was not reflex but bone-deep truth.

She hid the rosary under the thin pillow that night. It was more than a string of beads; it was a bridge back to the field of ordinary life. For twelve days the rosary sat like a quiet promise in her palm. Other inmates watched her differently—there is a particular hush given, in prisons, to someone with a date stamped on their future. On the morning of the third day before her execution, Jennifer asked a guard she trusted—Donna, a woman whose face was lined by decades of shifts—to grant one last request.

“I want to see the chapel,” Jennifer said, fingers through the beads. “The statue of the Virgin Mary.”

Donna blinked, then nodded. It would be unusual but not impossible. She ran the request up the chain and, two hours later, leaned into Jennifer’s cell with a flat smile. “Tomorrow at nine. Fifteen minutes.”

The chapel was modest: eight pews, a small altar, a statue of the Virgin Mary in plaster and faded paint, draped in a blue mantle. The paint chipped like old virtues, but in Jennifer’s eyes, it shone. She sat in the first row with the rosary in her hands, the glass beads cold and precise. She had stopped saying prayers a long time ago, had learned silence instead. But as the chapel’s clock ticked toward the fifteen-minute mark, something inside her loosened.

“I don’t know how to pray anymore,” she whispered to the statue, to air, to memory. “I don’t know if anyone listens. I don’t want a miracle. I just want not to be afraid.”

Time thinned. She mouthed half-remembered benedictions. She let the rosary slip through her fingers like the small, steady pulses of a heart. When Donna knocked, she rose and, for the first time in years, felt an ancient, fragile quiet bloom in the place where panic used to live.

That night she curled under the threadbare blanket and held the rosary until dawn, listening to the prison’s rhythm—the metallic clicks, the distant murmur of voices, the heavy footfalls she had learned to map. At two in the morning, the cell’s air shifted. It was not a drop in temperature but a settling, as if the world had pressed a hand against the lid of a box full of coals and they cooled at once. Light came—not from the overhead fluorescents, but a soft, golden glow pooling in the corner.

Jennifer sat up. For a moment she thought she was still dreaming. Then she saw the woman.

She was in a long white dress, with a blue mantle spilling over her shoulders. Her face was open like a dawn, full of something older than sorrow: unhurried mercy. Jennifer could not speak. The apparition did not move toward her; it stood at a gentle remove, hands slightly extended, palms up in a wordless welcome. The scent of roses poured through the room like a tide—fresh, impossible in that concrete space—and Jennifer’s knees weakened.

“Are you…?” she tried and failed. There were no words that fit what she was feeling. The woman did not speak but looked at her with such pure kindness that Jennifer felt each year of her prison life fold into something small and harmless.

She whispered, fractured and inconsequential, “Thank you.”

The light softened and receded like breath leaving a room. When it was gone, warmth remained—a settled, steady heat in her chest—and the scent of roses lingered like proof. She held the rosary as if it were a small living thing; it pulsed against her palm with the ordinariness of glass and string, yet felt new and entire.

At dawn, the guard on rounds paused at her cell and frowned. “Walsh, why does it smell like flowers in here?” Jennifer smiled a private, improbable smile and said nothing. Later, she would tell herself that perhaps the body had conjured a dream to soften the night, or that grief and fatigue make the brain the best of artists. But the scent of roses clung to her sleeve like a small, stubborn miracle.

The next morning, worn faces and nervous motions whirled around her. At nine, an official who had prepared for procedure called Director Foster’s phone. “You’re going to want to suspend everything,” the caller said, voice sharp with urgency.

Minutes later Director Margaret Foster—who had managed executions and the paperwork around them for twenty-five years—arrived out of breath in the place where Jennifer sat. “We’ve received a confession,” she told her, voice wobbling between professional and disbelieving. “Katherine Morris—she was on duty the night Mr. Kincaid died. She came forward last night to the police. She says she administered the wrong drug. She said she panicked and altered the records to put the blame on you.”

Jennifer listened as if she were underwater and the words were being translated into air at the surface. “Why now?” she managed.

Margaret looked at her with no answer that would settle the room. “She said she couldn’t live with it. She said she had a breakdown last night. She brought documents. She signed a confession.”

The cell spun and stilled all at once. Six years collapsed into one breath. Her knees gave under the weight of a future she had learned to bear as inevitable. She sank to the floor and clutched the rosary until the beads bit into her palm. Margaret knelt beside her, steadying, no pretenses of ritual in her hands—just human steadiness. “You’re going to be exonerated,” she said. “They’ll reopen the case. It may take days, but you’re innocent, Jennifer. You always were.”

The ensuing days were an avalanche. A judge suspended the execution, the confession was logged into record, evidence corroborated the truth, and lawyers moved with the strange, miraculous speed of people who had been waiting to be allowed to do what justice had been prevented from doing. Twenty days after the apparition, Jennifer walked through the prison gates as a free woman.

Outside, Emily and Aunt Linda waited like a small, fierce line of light. Emily’s face crumpled into joy that had been held like a fist now opened to the sky. “Mom!” she cried and ran and wrapped herself around Jennifer like a vine. The embrace was long, a reunion that smelled of the sun and the parking lot and of necks grown taller than they had been when they last clung together.

Three months later, Jennifer rented a small house with an overused stove and a yard with stubborn, brave grass. It was the kind of place that needed time and patience, which suited her. Emily came on weekends, and they rebuilt dinners and stories and the ordinary disputes that meant life was back in motion. Some nights worry woke her—memories like automatic films that flickered in the periphery—but the rosary sat on her dresser where she could touch it in the dark and remember warmth.

In June she got an interview at a community hospital. The staff regarded her with careful curiosity. There were questions and then, finally, a tentative opportunity. She started slowly—shifts at odd hours, a ward that needed someone who could listen to fear and stitch it up with small acts of kindness. The sting of distrust never left entirely; some people could not un-see headlines. But others saw her skill and the quiet steadiness of a woman who had survived an impossible night and returned to her calling.

On a bright Saturday morning, she and Emily walked through Willow Park. Children were scattered across the grass like confetti. A wooden bench sat in a pool of sunlight, and beside it was a bed of roses—soft pink, perfect in their bloom. Jennifer paused and leaned down, an old, familiar scent crossing her face like a memory retrieved from the folds of time.

“Mom? You okay?” Emily asked, glancing up, guitar lesson chatter spilling behind her.

Jennifer touched a petal. For a second the warmth washed over her again—the same intangible, gentle heat she had felt in the cell, the presence she could not wholly articulate. The smell of roses around the bed seemed to hold a promise, like a thing set in place to remind her of the arc she had traversed from shadow to open air.

“Thank you,” she whispered, not for the woman, not only for the scent, but for everyone who had stayed on the small, stubborn side of belief. She did not know whether to call what had happened a miracle or a convergence of guilt and confession and perfect timing. Maybe it was both. Maybe sometimes the two arrive at the same street corner and tip their hats at one another.

Emily squeezed her hand and said, “You’re smiling weird.”

“It’s a good weird,” Jennifer answered, and laughed, which felt like a bell’s clear note.

People asked about the apparition later—neighbors, coworkers, the curious who leaned close to a story with either hunger or skepticism. Jennifer never offered more than the facts: she had seen a woman in white whose kindness penetrated her with the force of a simple truth. She had smelled roses. She had not asked for reprieve; she had only asked not to be afraid. She did not know why things had unfolded as they did. But she had learned an important thing about belief: it did not require full explanation to be real.

“You know,” Aunt Linda said one evening over coffee, stirring it in a slow, careful circle, “I used to be one of those people who thought miracles were only for postcards. But seeing you come back… Terrible, impossible things happen, Jen. People break. But sometimes—sometimes the thing that saves you isn’t exactly what you imagine it will be. It’s a confession. It’s a truth finally told. It’s a small hand that holds yours until you can stand.”

Jennifer nodded. She kept the blue rosary in a box with a letter from her attorney and a photograph of Emily taken on the morning of her release. Sometimes she took it out and ran her fingers over the cold glass—small, ordinary objects that had become ancient icons. Beside the box she kept the receipt for a plain wooden bench she had purchased for the front yard, the bench she wanted to put beneath the window so that Emily could sit with her when she needed to talk.

On anniversaries she sometimes returned to the chapel at St. Agnes. The statue had been touched by a thousand hands. The paint had faded a little more. Once, an old nun who remembered her from before asked quietly, “Do you think she came because Emily prayed?”

Jennifer looked at the statue, at the light that leaked in through the high windows, and thought of the soft face she had seen two mornings in a cell made small by bars and impossible endings. “Maybe,” she said. “Maybe Emily’s prayers were a small cord someone was tugging on.”

“Or,” the nun replied, “maybe you were tugging, too. You didn’t know it.”

The years did not erase the scabs. There were moments of flashback, corridors that smelled like antiseptic that sent her heart into memory. Sometimes she woke and felt the momentum of a past life tugging her, but the threads had different weights now. Hope was not a naive thing living only in children; it had worn the skin of the weary and learned to last.

When Emily left for college, they cried on the porch until the sun lowered and painted the sky the color of old roses. “You’ll call me every day,” Jennifer demanded, half joking, half requiring.

“Every day,” Emily promised, and meant it.

People told the story of the blue rosary in different tones—some with the hush of a miracle retold in neighborhoods where prayer was currency; others with the exasperated shrug of those who needed proof in the form of bloodlines and documents. The defense papers, the confession, the reopened case—those were the concrete things that freed her. But there was a quieter ledger written in scent and warmth, in the small miracle of a daughter’s unfaltering belief, in the way a woman’s voice in the dark can reconfigure what the world calls possible.

One evening, as rain threaded the windows and made the streetlights shake like a candle through glass, Jennifer took out the rosary and held each bead in the light. She traced the worn glass with a thumb and thought of the woman in white, of Margaret’s shaking voice when she’d delivered the news, of the small, brave girl who had crossed state lines to ask a statue for mercy. She chose not to spend her life proving the unprovable. Instead, she chose to be a steward of what she had been given: a second life lived deliberately.

“Do you ever think about going back to nursing full-time?” Emily asked over the phone as she sat with a cup of late-night coffee.

“I do,” Jennifer said. “But I don’t think I’ll ever go back for the reasons I left. I’ll go back because I still believe in the small work—the kind that puts bandages on things that matter.”

“You always were the best at that,” Emily said. Her daughter’s voice carried across state lines like a bridge.

Outside her window, the roses in the park had yielded to the season, but they would be back. Jennifer liked to believe that life, like roses, kept finding a way to bloom after frost. It was not a tidy theology. It was not a perfect answer. It was, she thought, enough to keep walking forward.

Sometimes people asked Jennifer whether she had become devout after the experience, whether she lived the rest of her days under a banner of faith. She smiled. “I don’t know,” she would reply. “All I know is I never felt alone again. And that, whether you call it prayer or coincidence or the moral weight finally tipping, is a very big thing.”

At the bench in the park, beneath a row of blooming roses on a Saturday morning, she and Emily sat together and watched other lives unspool and reweave, small human things: a child dropping an ice cream, an old couple holding hands, a man reading a book with the sound of wind in his ears. Jennifer breathed in the smell of roses, and it was enough—warmth in her chest like a promise kept.

“Blue rosary,” she said to herself, a private benediction that tasted like forgiveness. She tucked the image into her pocket, let the world unclench, and then, with a laugh at the simple sacredness of ordinary miracles, she stood and walked toward the future with Emily at her side.

News

The Twins Separated at Auction… When They Reunited, One Was a Mistress

ELI CARTER HARGROVE Beloved Son Beloved. Son. Two words that now tasted like a lie. “What’s your name?” the billionaire…

The Beautiful Slave Who Married Both the Colonel and His Wife – No One at the Plantation Understood

Isaiah held a bucket with wilted carnations like he’d been sent on an errand by someone who didn’t notice winter….

The White Mistress Who Had Her Slave’s Baby… And Stole His Entire Fortune

His eyes were huge. Not just scared. Certain. Elliot’s guard stepped forward. “Hey, kid, this area is—” “Wait.” Elliot’s voice…

The Sick Slave Girl Sold for Two Coins — But Her Final Words Haunted the Plantation Forever

Words. Loved beyond words. Ethan wanted to laugh at the cruelty of it. He had buried his son with words…

In 1847, a Widow Chose Her Tallest Slave for Her Five Daughters… to Create a New Bloodline

Thin as a thread. “Da… ddy…” The billionaire’s face went pale in a way money couldn’t fix. He jerked back…

The master of Mississippi always chose the weakest slave to fight — but that day, he chose wrong

The boy stood a few steps away, half-hidden behind a leaning headstone like it was a shield. He couldn’t have…

End of content

No more pages to load