The half-mile that followed was an old story made of timber, of houses that had been added to and soldered like armor through decades. The Blackwood farmhouse rose from the clearing like a jaw, its chimneys breathing thin smoke that smelled of wood fire and something animal. Curtains twitched as they passed. Figures moved in and out of shadow; one small child darted across the yard on all fours and then stood again, small and almost human when seen in profile. Morgan’s clipboard felt suddenly frivolous in a place that set the teeth on edge.

Abraham Blackwood met them on the porch. He was a large man whose bulk belonged to a different era; his gait was wrong in the thick way of something leaning forward to listen rather than to walk. When he smiled, something in the angles of his mouth made the expression read like a warning.

“Anthropologists.” The word fell into the porch air like a pebble. “You tread private ground.”

Morgan introduced herself, showed the ID. “We’d like to learn about your family’s history. How you’ve maintained your way of life.”

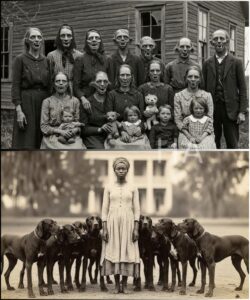

Abraham regarded Morgan as if weighing whether words could feed his curiosity. Behind him curtains drew back and faces peered, some with a jut of jaw, some with ears that caught more of the light. The family crest above the doorway — humans and canines intertwined — might have been old pride, or the soft confession of a secret kept in plain sight.

“You may photograph the property,” Abraham said finally, “but not the family, not without permission.”

They were ushered inside. The house smelled of smoke and venison and something muskier beneath it, a tang that sat in the mouth like promise or threat. The common room was a museum of craft and patience: hand-hewn furniture, battered books with spines like ridges of old rivers, a single iron kettle singing on the hearth. Children watched from doorways, adults observed through narrowed eyes. They fed them meat barely roasted, and the family members ate with the animal competence that made diners in the nearest town tell hushed stories.

Martha sat beside Abraham and moved in a way that made Morgan’s scalp prickle. Even at rest Martha’s shoulders humped forward a little; her hands were long; her nostrils flared almost as if she were testing the air for its weaknesses. The family spoke in clipped sentences interwoven with a rhythm that sounded like a language hardened by the wind and the time they had spent hearing themselves speak it.

“We keep to old ways,” Martha told Morgan when they asked about pregnancy, naming, law. “We sleep with the dogs just as Eli taught.”

A child — Sarah, seven or eight, Morgan later learned — darted across the room on hands and knees and then popped up with a grin so quick it was almost hidden. “We sleep together,” she chirped, “and our dogs keep the cold out and the wolves away.”

The laugh that left the oldest woman at the table started human and fell into a thing like a yodel, and Morgan felt the air contract with the kind of discomfort that is part dread and part the cold hand of professional exhilaration. There were the obvious signs — elongated jaws at the margins of smiles, eyes that reflected light like polished amber, postures that favored the forward motion of an animal about to leap. The children seemed less altered. The elders had features receding into something not fully human.

Abraham told them the story as if reading from a family bible. Eli Blackwood, home from war in 1872, found three wild dogs in a blizzard and kept them. They slept in his bed. The dogs warmed him and steadied him. His son slept with them. The family grew accustomed to scent and shift. Generation by generation the line blurred the fence between pets and kin.

“Evolution,” Abraham said, the word almost reverential. “We are becoming more. Stronger. Connected.”

Morgan cataloged sentences in her head: eight generations, isolation, ritual, physical changes that intensified with age. She asked the scientific questions of the night and watched the family answer with rituals and metaphors and the odd defensive shove of irony. At dinner she caught sight of the silverware: toothmarks on forks, little grooves where it looked as if teeth had been used like tools. The family ate with hands when hungry. At the head of the table Abraham spoke of a gathering that would be held by moonlight. “We honor our true nature,” he said. “We give thanks to the pack.”

That night, after Martha escorted them to a single guest room and closed the door with the etiquette of someone who had counted supply and furnace against a houseful of hungry mouths, Morgan set her recorder on the nightstand. Leo teased her with a joke about ethnographic prudence. They fell into an uneasy sleep. The house sang around them: low howls up and down the stairwell, a chorus that was half lament and half triumph. Around two in the morning the sound tightened into rhythmic thumping in the hall and something like barking laughter. Leo’s camera lay on the bed; his fingers found it suddenly, and then there was a smaller knock.

Sarah’s small frame slid under the door. Her eyes were glassy with the shine of someone who cried and hadn’t yet learned to stop. She whispered a warning: “They hunt on full moon nights.” She told them the children had a tunnel network, that some had resisted and were locked away. “Don’t come out,” she said, “until morning.”

Morgan watched Sarah go, then read Eli’s journal on the shelf until the paper bent under the weight of history and the lamps threw shapes that looked like animals. Eli’s entries read like the rationalization of a man who had found relief — and then a man who recorded changes. A growl where a voice used to be. Sharper night sight. A jaw that jutted. He wrote about the first marriages that accepted the changes and the first wife who left. He wrote about Eli’s belief that the dog blood made them better. The chickens on the page seemed to cluck with a different cadence. Morgan held the book and felt the thinned thread of the family’s self-justification.

In the morning Leo disappeared before the sun woke and the fog lingered low. He walked the property and found the family cemetery, headstones that shifted through the language of a family evolving into its shape: pawprints beside hand impressions, faces etched half human, half coursing muzzle. One headstone, more elaborate than the rest, bore Eli’s name with a carved likeness that blended canine and man. There were other marks — a mass grave near the boundary: “Outsiders,” the crude marker said.

Leo’s camera found proof and then the proof vanished. He claimed his memory failed to find the images; his photos of the graves deleted themselves. When he showed Morgan the screen the files scrolled like a blink and then were gone. Technology, Abraham suggested when the subject came up, was unreliable on Blackwood land. Things didn’t work right. The air stiffened with the kind of logic that shields a family from horror.

They should have left. They should have taken Jason’s truck when it idled at the fork and gone back to Milbrook and told the world. But curiosity is a hungry animal and feasts on things that scare others. They stayed for dinner under a sky that broke open and poured rain like baptism.

After dinner, with the storm rolling in and the house filling with a smell that was a mix of wet fur and ancient hearth, Abraham took them to an inner hallway where leather-bound journals sat like unread generations. Morgan found Eli’s heavy book again and, tucked between pages, a mention of a doctor. A name. A ledger entry about experiments, notes on something that passed in saliva, a suggestion of contagion and a doctor’s attempts at an antidote. Morgan’s heart leapt with the cold surge of possibility: if there was a way to slow the progression, it would be in those notes.

They were led to one-room for the night, and the house unfurled its rituals around them. The family prepared. The porch filled with shadows that belonged to beings between species. At dusk, a child — Sarah — watched them with eyes that shone like coin; she slipped them a key and a map scribbled on the wall. She said the cellar held cages for the resistant ones, people who fought and were placed away because the family thought it kinder than seeing them at dinner. A child’s hands are small and know the shape of tunnels adults no longer remember. Morgan took the key. Leo took the camera. The vials in the doctor’s notes were a thin hope tucked between pages.

They slipped into the cellar; the key fit. The stairs smelled of damp and old animals. Iron cages lined the far wall. Bodies crouched within them, faces half-muzzle, hands curled into fingered paws; they whimpered when the light found them. On a sign above the cages someone had written in a slanted hand: “The resistant ones.” The sight stopped the earth in Morgan’s chest and the scientist in her did not have words large enough to contain the humanity and the horror. She put her hand on a face that belonged to Jacob and the eyes, human enough once, found her and begged silently.

Hope is awkward and dangerous. A tunnel beyond the cages led into an old network, and when they moved toward it the house grew loud with the sound of ritual. Abraham led the family into the cellar with a ceremonial trough of dark liquid. “The blood of the hunt strengthens the pack,” he said. He had a voice that trembled the air into grief and command. Jacob begged and they made him drink. “Drink,” Abraham told him. “Embrace your nature.” Jacob fought. They forced his head down.

Morgan’s breath left her chest and the sound of it made the stone floor grind. She had not come to become a moral actor. She had come to observe. But observation is a thin comfort when the human folds into the animal in front of you. She felt the footstep of duty shift under her — scientist, witness, savior. She and Leo fled into the child’s tunnels.

They crawled. The passages were narrow as a ribcage. The tunnels smelled like old fear and the soft tang of adolescent self-denial. At a fork they ran into Martha blocking the path in a way that proved motherhood changes alongside other things. Her body had shifted further than any at the table; she had the bend of a hunter who had learned to run on the edges of the pack. “You shouldn’t be here,” she said. Her voice had the intonation of a promise and a threat.

Morgan tried to bargain. She spoke Sarah’s name. Maybe Sarah could help. Martha’s eyes flickered and, for a rational moment, something like sorrow — or its skeleton — passed through them. But Abraham found them. The hallways filled with footfalls and the house began to smell of rain and hunted things. Martha’s hesitation was a crack, and through it Morgan and Leo slid into a smaller passage. They crawled until bones protested, until the child’s hideaway opened into a clearing that smelled of sap and moonlight. There was Sarah with a small vial and a battered notebook — the doctor’s work, a cobbled formula that had once helped some children.

The moment they found Sarah the problem pivoted. She was not merely frightened; she was changing. Her jaw had begun to edge forward; her nails were becoming talons in thin increments; the fever in her small body lit like a warning flare. Sarah told them she had been given small doses at the gatherings to prepare her, and that the doctor’s treatments had helped — for a time. The doctor had tried to study them and then, the way Sarah said it, they had “made him eat the ground” — which meant something worse than murder; it meant they had gutted the outside and burned the books. Sarah had saved what she could.

Morgan read the notes. The doctor suspected a transmissible agent — prion-like, or something that rewired gene expression across lifespans when embedded in saliva, when passed through generations by ritual proximity. He had mixed compounds to slow the expression, to prevent the cascade that made a jaw extend and a backbone restructure. The vials were little miracles of chemistry with less hard evidence than hope.

They had to move. The tunnels were compromised. The family sang in a tone that broke human throats and stitched animal throat into the same phonic cloth. The house spilled creatures into the woods. Abraham led the hunt. The pack hunted the traitors who would leave.

They ran the stream route Sarah had marked. The Blackwoods anticipated the stream tactic and placed pickets in the underbrush. Wood and breath met like weather until Leo lifted a branch and struck with the ferocity of a man who had backed his heart into a corner and found courage there. He struck Abraham with a branch that splintered but only unnerved Abraham. Leo’s arm broke in the struggle; hands bigger than squirrels’ clamped around him, but he dragged free long enough for Morgan to shove Sarah and herself ahead into trees.

Abraham, an animal with a man’s cunning and a father’s patience, let them go for a moment. “Family becomes pack,” he crooned as if the words were epiphany. “Outsiders become pack or prey.” The rest was a hunt that left Leo caught and dragged back toward the pond where the family was gathering. Morgan and Sarah ran until the lungs could not contract more than a syllable before breaking.

The clearing where the family had assembled was a cathedral of bones and firelight. The altar was a slab of stone. The trough of dark liquid steamed. A rabbit bled and Abraham called for witnesses. “Eight generations,” he intoned. “Eight generations of warming beds and shared mouths.” He raised his arms toward the moon and the family chanted something older than language. Leo was tied to a post and the crowd circled like a wolf pack starved for the show of it. Faces that used to belong to human kin now had muzzles; they lopped and barked in the hollow and the sound made splinters in Morgan’s teeth.

Morgan could have surrendered Sarah to this and the world could have rationalized the brutal anthropology of it all. She did not. She edged along the ringed clearing with the doctor’s notebook beating the rhythm of her logic against her ribs. This was medicine and mercy and the content of a whole career and she would not let it all burn into festering legend.

Abraham lifted a rabbit’s throat and the blood, which might have been medicine or ritual, dripped into the bowl. He called for a volunteer. He fixed his gaze on Leo and then on Morgan like an alpha choosing the next month’s leader. Morgan stepped forward.

“You’ll not allow us to choose,” she said, voice steadier than she felt. “This is not ancestry and gods. This is suffering concealed as tradition. You can have this if it comforts you. But you have children.”

For the first time since she had arrived the edges of Abraham’s eyes sharpened like a blade. There was something like pain there — not the physical pain of teeth and breath changing, but the existential hurt of a lineage at the edge of being changed from itself. “You outsiders do not understand,” he said. “We are home.”

“No,” Morgan answered. “You’re people.”

Sandwiched between the rising smoke and the low chant Morgan read through the doctor’s notes in the little time her voice bought, while Martha’s gaze shifted in private. There was a compound in the notebook — crude, dangerous, but likely to interrupt the chain reaction. It was not a cure. There is no immediate reversal of eight generations. But it promised to slow the process, to blunt the wire that made jaws unhinge and spines reconfigure so that treatments might find purchase and real medicine could be brought to bear. Morgan’s hands shook as she measured powders in the dark by moonlight. She had to make choices: the vial for a child or a larger dose for the altar to disrupt the ritual? She chose both. It was a gamble with the scale of lives.

She moved like a woman possessed. While the family chanted, she slipped forward and poured a dose into Leo’s mouth, cramming it in with the force of someone who understands that the difference between witness and casualty is sometimes a breath. Leo choked and swallowed. She pressed another into Sarah’s hand through the ring of bodies, and then, while no one watched — or perhaps while they watched and consented like a collective crime — Morgan lifted the bowl at the altar and poured the remainder into Abraham’s trough.

It was a small rebellion: blood in the bowl, chemical interference between the pack’s ceremony and the script that had played for generations. The effect was immediate and not what she expected. Abraham’s chant faltered. His nostrils flared. He staggered as if struck, and his jaws snapped like a trap closing on nothing. The others began to bark in confusion, an animal noise pierced by human questions. The ritual halted. A silence cut the clearing.

What Morgan had done does not fit easily in the categories history likes to keep. The concoction was imperfect; its mechanism uncertain; the long-term effects would be debated by scientists and theologians and, Morgan suspected, by censors who love tidy narratives. For the instant of that night, it opened a crack in the armor of inevitability. Faces that had begun to harden into muzzles softened for the first time in a generation; eyes that had clouded to an amber sheen flickered with something like memory. Jacob’s battered face — the man forced earlier to drink — turned upward and found his sister’s eyes with uncomprehending grief.

Abraham fell to his knees, hands clawing at the earth as if some force were pulling him toward a human shore. The chant emptied into a hush. In that hush something broke like ice. Some of the older family members continued to twitch and bark, ungoverned by the thin human sinew. Some, like Martha, moaned with the ache of two worlds. But the children — Sarah and the others — coughed and blinked and looked as if they’d had sleep forced upon them and now came to again.

Martha collapsed as if the entire body had been reminded of its humanity. She fell into her daughter’s arms and sobbed in a sound that was only partly an animal’s warning and mostly something that spelled out a mother’s shame. Abraham’s hands trembled. For a long suspended breath he lifted his face and saw Morgan as if seeing her for the first time.

“You altered the pack’s blood,” he said without menace. There was a fracture in his voice that might have been grief.

“I tried to stop that from being the only story you can tell your children,” Morgan said. She could not promise cure, only the possibility of choice. The dram she had poured into the trough would not reverse eight generations in a night. But it would slow the progression. It would give the children a margin to breathe. It would allow the world outside the ridge to walk in with doctors and social workers and, if the Blackwoods chose it, real help.

The decision that followed was quieter than she expected. Abraham’s gaze moved across the clearing, across faces that had once sung lullabies and had instead learned to sing barks. A child named Caleb — a boy with a jaw halfway grown into a muzzle — watched his father and then turned his head away. It would have been majestic if it were not so painfully human.

There was a vote that night, not in circle chanting and certainly not by barking. Abraham, the alpha, sat and listened while people spoke for the first time in a generation without a script. Some wanted the old way. They feared outsiders and what treatment might do. Some wanted another course and were tired of the half-life of their condition. The children clung to Martha and to Sarah. Many voices were hoarse with habit.

Dawn did not offer a tidy answer. It offered choices. A handful of the elders decided to stay and embrace the change; the body had hardened and to them the animal was not less than human but the purest human they had ever known. A portion of the adults — Martha among them — wept and asked for medicine and time to learn what it meant to be both. Abraham, who had guided the family through its rituals for decades, did not leave the land. He did something harder. He let the gates open.

Jason from Milbrook arrived at dawn: the truck’s tires had ground ruts into the mud and he had come because someone had called the town. Darlene had not called the sheriff; she had called someone else. People in small towns understand that some problems need doctors and not blue uniforms. Morgan had, during the night, managed to send a location note that scrambled for a pocket of signal; it had reached a friend at the university. The friend had decided to call old favors and older methods. The world does not always act with the speed a situation demands, but it finds its way.

Medical teams arrived by late morning. The sight of them frightened half the pack and angered another half. Some had to be sedated; others welcomed needles like strangers welcomed rain. The doctor’s concoction was crude but useful; with it the pharmaceutical team could create stabilizing agents and design diagnostics that might understand whatever feline-prion-bent virus or epigenetic cascade had braided itself into Blackwood DNA. Geneticists called it an unprecedented cluster, not a single disease but an interaction between culture and biology more intimate than textbooks like to admit. Morgan published papers for the sake of truth and history, but she also scrubbed names from those articles. The Blackwoods did not want themselves to be an exhibit.

Humanitarian teams set up a small clinic between the house and the road. Darlene and Earl and other Milbrook folks brought food and blankets and, timidly, a willingness to see people for what they were: kin with a variation. Some of the Blackwoods accepted help. Some went back inside the house to the world they had always chosen, even with its animal calls and strict rites. The community around Canine Valley turned, halting as a child learning to walk, toward something like understanding.

Leo’s arm healed with the grace of a competent doctor and a concussion of pain. He returned to his camera because photographing bears witness in ways words sometimes do not. He also wrote to his mother for the first time in months and told her when he would return. Sarah took the hospital’s white floor like a stage of new possibility. The vial Morgan gave had slowed her transformation enough that with months of treatment — with therapies to slow the prion, with nutrition and physical therapy — she might live a life that was not ruled by her biology alone. It would not be easy. It would not be certain. But it would be her life.

Abraham did not leave the property. He watched the road. In the mornings he walked the edge of the cemetery and tended the stones with a care that surprised the simple narrative people tried to give him. In his old age he could have chosen to become a legend of cruelty or a martyr of stubbornness. He chose instead to listen and learn. His stance around the family softened in the way of someone learning sentences.

The townspeople of Milbrook needed time. So did the Blackwoods. Dozens of meetings took place in the diner where coffee was no longer poured in judgment but in cautious fellowship. Darlene set extra chairs at the counter. Earl took a few days off to fish and think and found that fish didn’t care for the way a family decided to be. Conversations were small and strained and then they weren’t. People are not neat patterns; they are knotted skeins that when drawn out, reveal common thread.

Morgan wrote long reports and hid the names of the people who had put their bodies on the line for her knowledge. She insisted that the articles be framed with ethics and a request: if a scientist comes to a closed place, let the people choose whether to open the door. She sat at the bedside of someone who had been in a cage and listened to a story that had been told in riffs and animal lunges and found the human core under it. She helped build a clinic. She became, in time, part of the city’s memory — not the invader but the doctor who brought choices.

There were darker nights. Some of the older Blackwoods could not find their way back from the animal’s call and declined into shapes that the rest of the family called holy. There were moments of violence. There were also quiet afternoons when smell and song found their proper place and people, freed from ceremony, learned to play with children in ways that did not require a hunt.

Years later, when a journalist more interested in neat morality than messy truth tried to write the Blackwood story as myth, the town corrected him. “They were people,” Darlene told him, folding her hands around a mug that had seen more than ten winters. “They were people who chose.” Sarah grew into a woman whose jaw carried a small, stubborn verso of the change and who learned to speak with a tone that had the heart of both worlds. She would sometimes stroll down to the diner and show tourists how to feed the dogs that now lived in real kennels — real dogs that preferred kibble to blood and would bark at a mail carrier like any good pet.

Morgan wrote a paper that won acclaim for its humane clarity. She titled it as dry scholars do, but the footnotes made room for small things: a child’s key hidden beneath a stone, a journal bound in animal hide that smelled of rain, a recipe for an antidote that was part mercy and part chemistry. She took photographs that Leo had shot, some of which she refused to publish because they were too naked in the way they showed a family’s sorrow.

Abraham died several years after they first came. He passed in the house with the windows open because he had a stubborn affection for the wind. At the graveside, the crowd was a pattern of humans and a few family members who had chosen to remain with forms that had learned to bend a little back toward being human. Some of the older ones howled and then wept. Some of the townspeople did the same. The ritual at the end was less a satin murder and more a hand offered.

When they lowered Abraham into the ground, some of the family — the children who had been saved, the adults who learned to be something other than a ritual — sang a song that was both human and animal. It was not the brutal, exclusionary thing of the past. It was a lullaby that promised warmth and shelter and room to choose.

Morgan stood at the edge of the grave and felt for a moment the heavy, quietly human grief of one who makes a life out of stepping into other people’s darkness: she had watched a family break and begin again in ways that would be argued over by scientists and theologians and gourmands of sensational headlines. None of that mattered to the small, slow work that happened afterward: the children placed in schools, the therapy sessions, the community kitchens that learned to feed both animals and people without flinching.

On the day Sarah left for the city to begin training as a nurse — a job chosen because it would let her keep helping children who might be in pain she once knew herself — she hugged Morgan and whispered, “You saved me.”

Morgan felt something in her chest that was part pride and all human relief. “You saved yourself,” she said.

“Maybe,” Sarah answered, and then she smiled in a way that showed a little too much tooth for comfort and a little too much kindness to be anything but a person’s first truth. She climbed into a truck that took her down the old road through the trees and into a life that would be complicated and ordinary and, by any good account, human.

In the years that followed, the Blackwood property did not vanish into legend. It became part of a complicated catalog. Some nights the dogs still howled, but the howling was not always a threat. It was sometimes an invitation. People came — not intruders but visitors — bearing food and benches and the occasional doctor. They learned how to listen. They offered help and waited for consent. And in the hollow, when wind brushed the sills of the farmhouse, the tall grasses said the same thing they always had: the world is big enough to hold the strange and the ordinary, if the people within it remember to be kind.

Morgan put Eli’s journal back on the shelf when she could. She read it again, and she read it to a class of students who would learn the difference between curiosity and exploitation and who would argue sometimes and sometimes listen. She taught them that the human heart is rarely tidy. She taught them that a single act of science can carry the weight of centuries and that the best discoveries are those that don’t take place at the expense of another’s life.

Late, sometimes, she would drive back up toward the ridge for no reason other than to see the house. On clear nights she would stop the car and listen. A sound would rise from the clearing — a note that caught somewhere between a bark and a lullaby — and she would think, briefly, of how fragile the lines are between kindness and survival, between rites and cruelty, between what we call progress and what we call surrender.

She would think of Leo, who learned to fix things and keep his hands busy so his heart could rest; of Sarah, who learned to stitch other people back together; of Abraham, who learned that being an alpha does not mean closing the door but choosing who stands inside it and how they are seen; and of the town, which in its own slow way learned to see people not as monsters or myths, but as neighbors.

Canine Valley did not end in horror. It did not finish as a fairy tale. It unraveled into a prismatic life of hard choices and small mercies. And in the years the valley kept weathering storms, people would sometimes tell this story with the thrill of the macabre and sometimes, with the more difficult tenderness of the human: that a family had once shared beds with dogs and that the bloodline had become monstrous — and that, in the end, people had chosen each other again.

News

A Billionaire CEO Saved A Single Dad’s Dying Daughter Just To Get Her Pregnant Then…

“Was it a transaction?” the reporter asked, voice greasy with delight. “It was a desperate man trying to save his…

“Come With Me…” the Ex-Navy SEAL Said — After Seeing the Widow and Her Kids Alone in the Blizzard

Inside the air was slow to warm, but it softened around them, wrapped them the way someone wraps a small…

“Sir, This Painting. I Drew It When I Was 6.” I Told the Gallery Owner. “That’s Impossible,” He Said

Late that night the social worker had come. A thin man—he smiled too much, like a photograph—who said her mother…

The Evil Beneath the Mountain — The Ferrell Sisters’ Breeding Cellar Exposed

Maps like that are thin things; they are only directions until they save your life. When the sheriff and four…

The Mother Who Tested Her Son’s Manhood on His Sisters- Vermont Tradition 1856

“Rats in the walls,” she said. “Old house. Winter gets ‘em.” He did not press her. He smiled, mounted his…

🌟 MARY’S LAMB: A STORY THAT CHANGED THE WORLD

CHAPTER III — THE SCHOOLHOUSE SURPRISE Spring arrived, carrying with it laughter, chores, and lessons at the small red schoolhouse…

End of content

No more pages to load