I smiled. It surprised both of us how serene it felt. “Have you met my husband yet?” I asked.

Her face flickered. Confusion flushed to her cheeks and then pale shock. Behind her, Nathan’s posture stiffened.

“Your—husband?” she repeated slowly, as if tasting the word. “You’re married?”

I held my ground. Zachary came then, as if called. He had been waiting across the room with our father, a steady presence in a quiet charcoal suit, his hands folded, his eyes soft when they met mine. The room seemed to tilt, measured in heartbeats.

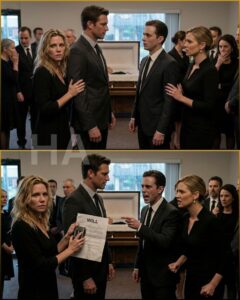

When their eyes met—Nathan’s and Zachary’s—Nathan’s confident, practiced smile faltered. Color drained from his face.

“Foster,” he said, a name like a thrown gauntlet.

“Reynolds,” Zachary answered, calm as a clock. “It’s been… what, seven years? Macintosh acquiring Inotech instead of your client. The court filings were a saga.”

Nathan’s mouth thinned. Some of the funeral-goers stiffened, recognizing the ripple—two men from the same headlines now standing face to face in the shadow of my mother’s casket. Small talk evaporated. I felt a thousand fragments of the past click together with one quiet certainty: this was perfectly, beautifully inevitable.

Later, when the priest called for quiet, I walked to the lectern. My voice wasn’t as steady as I thought—my hand shook—but the words came true and honest, the ones I had promised my mother I would say: about garden chairs with chipped paint that lived longer than they should, about the blue dress she wore to Sunday brunch the year I graduated, about how she braided our hair and pretended not to see us scraping knees on the swing set. I finished and stepped down. Stephanie stood after me, voice cracking, remembering a memory where our mother had saved two identical cupcakes for us and then left a note in each lunchbox, different messages every day.

For the first time that day, I held my sister’s hand in the receiving room as the rain softened our grief on the walk to the cemetery. It was a small, trembling truce.

A week earlier, the man who had once been mine had been the cause of the largest shard of my life breaking.

I wasn’t naïve. I’d always known Nathan for what he was: a brilliant public speaker with a smile that filled rooms, an appetite for prizes and praise. He was also the self-made tech millionaire who loved the press more than privacy. When we met at a charity gala, the evenings spun easily—yachts, weekends on the Vineyard, boxed seats and lavish dinners. The relationship moved quickly; the ring came on an unassuming yacht by moonlight. I’d said yes. My mother had cried and folded her hands, already conjuring weddings.

Stephanie had been my maid of honor; we’d tried very hard to be sisters who had grown past competition. But there had always been that older-sister younger-sister dynamic—each of us measured against the other in small and quiet ways. Stephanie—lithe, sharp, practiced in the art of charm—had always wanted what I had. That doesn’t excuse her. It explains, perhaps, where the seeds were planted.

Three months before our planned wedding, things changed. Nathan grew distant: meetings, late nights, the steady hum of business calls. He began to taste patience thin with irritation. I found a sapphire earring in his car—mine to the memory, the earrings Grandma had given Stephanie. He lied. She lied. I walked into Nathan’s office one lunch with a sandwich and found him entwined with my sister behind the glass wall. The scene etched itself into me: their mouths, their hands, the absolute stillness of them when I pushed the door open.

He said it “just happened.” She shrugged. I felt the ground open.

They moved in together within a month. They married in a white dress in a courthouse and published photos like a careless prayer on social media. I left Boston. I moved to Chicago, rebuilt a life from the rubble. It was where I learned to breathe again.

That life led me, years later, to Zachary Foster.

He was not flamboyant. His humor was dry, his smile rarer. At a tech conference in San Francisco he asked me about marketing metrics over coffee, without an ounce of judgment. He listened. He lent a patient hand when I panicked on dates. He didn’t offer grand gestures so much as the repeated, steady work of being there. We married in a small Chicago venue with thirty guests while the river glittered behind us. Zachary’s vows were not showy: “I will remember to be gentle. I will remember to be brave. I will remember you.”

He also had a history—one that became the curious fulcrum of the funeral day. Years earlier, Zachary had backed a scrappy startup that became the opposite of Nathan’s golden pick. Where Nathan’s clients stumbled, Zachary’s investments soared. The rivalry between Foster and Reynolds had been the kind printed in dry financial pages: lawsuits, late-night boardroom battles, public accusations. Nathan lost weight around that time. The man who wore my ring had been, in the end, as vulnerable to business ruin as to moral failing.

At the funeral reception, people clustered in polite knots around platters of chicken and egg salad. Business acquaintances took the opportunity to exchange numbers—because in spaces where money changes hands, even grief can feel like a small currency. Nathan drank too much, laughter thin. He cornered one of my father’s friends, trying to pivot to work talk, but the way he kept glancing at Zachary betrayed him—some private alarm ringing.

Later, while I helped my father sort through my mother’s closet, I found her journal, the leather once-worn edges showing through. The last entries were painful to read—her fingers had a way of making everything practical and full of love: “Promise me you’ll try,” she had written. “They are your daughters. Make room for them both.”

That night, when the house settled and rain tapped on the panes, Stephanie came to the back door. She looked small and raw without Nathan’s shadow at her side. Her mascara had streaked. For the first time in years, she sat without the posture of someone who had polished herself for the world.

“Where’s Nathan?” I asked, pouring coffee because it felt like something to do with my hands.

“At home,” she said. “He doesn’t know I’m here. I… I had to be here alone.”

She told me, haltingly and then in a rush: Nathan’s lavish life was fragile. Acquisitions disguised debts. The house in Beacon Hill was mortgaged beyond sense; the trips were charged to accounts that bled; the social photographs hid a man who checked bank statements at midnight and then railed about the treachery of people who’d once been colleagues. She’d stayed for reputation and, selfishly, for security. The glimmer had been worth a price she didn’t realize would come due.

“I’ve been planning to leave,” she said, the confession tumbling out like coins from a badly held purse. “I’ve been seeing a lawyer. I can’t live like this. I can’t keep pretending.”

My first impulse was unforgiving. I had not built a life to watch her dismantle it. But the image of her small on the porch, the truth raw on her tongue, and the journal’s plea to “try” softened something I had kept hard for years. Grief does strange things to old armor; it corrodes it.

We did not reconcile fully that night. We did, however, begin to stitch something.

The real pivot came at the cemetery when Nathan’s eyes had met Zachary’s. After the service, Nathan cornered me on the edge of the reception. “What was that?” he demanded, voice low. “Are you using him to humiliate me?”

“No,” I said, and realized I meant it more than I thought. “I didn’t plan anything. Zachary is my husband.”

Nathan’s laugh was a brittle thing. “Of course he is. The enemy marries the survivor.”

Zachary didn’t seek him out, but he didn’t avoid him either. When the business acquaintances circled like sharks smelling blood, Zachary spoke plainly, not with the need to gloat but with the economy of someone whose reputation had been hard-won. Details leaked—threads of old battles: which companies backed which startups, who had made a bad call, who had taken a risk. In private, Zachary later told me that when he’d heard my name at that San Francisco conference, something in him had paused. He’d been a judge in business long enough to know when to bet on people who were not performance metrics but who stayed.

“Why didn’t you tell me?” I asked him later that week, sitting under the gentle hum of my parents’ kitchen light. He folded his hands like a man who had learned the art of patience.

“I wanted you to know me first,” he said simply. “Not a past headline.”

He kissed my forehead. “Besides,” he added, a little smile touching the corner of his mouth, “if you’d met me with the baggage in the open, you may never have seen who I actually am.”

The weeks after the funeral were strange tectonic shifts. Father, freed from the daily orchestration that had kept him steady, sagged in the seat at the kitchen table in a way that made me hold the phone to my ear with a calm I had to borrow. Stephanie moved out of Beacon Hill. I watched from afar as the woman who had once worn my ring untangled herself from the life she’d built on borrowed luster. It was petty comfort to see hints of the façade crumble; it was also quietly painful.

And yet, in the new life I had built, things grew the way a winter garden unfurls under patient hands. Zachary and I renovated a brownstone and turned boxes into walls of photographs. I was promoted. We tried for a child and found that some things require patience and that some gifts were measured in years.

Sometimes, late at night, when the nursery light glowed and the house hummed, I would think about the night I walked into Nathan’s office and how shattering that betrayal had been. I would think too about my mother’s hand on my cheek as she told me to try. In the end, what it taught me most was not a lesson in justice—no one was spared the messy calculus of choices—but a lesson in direction.

When Stephanie eventually called to tell me the divorce had finalized, neither of us gushed. We traded the small currency of used furniture and the names of lawyers. “Are you okay?” I asked, remembering her on the porch.

“No,” she admitted. “Not yet. But I can breathe.”

“Good,” I said. “Breathe.”

There were days when guilt pressed in like fog—an irrational, heavy thing that made me consider whether I should have railed harder, forgiven sooner, condemned more quickly. Guilt is a greedy tenant. But forgiveness, when it came, felt more like a release and less like a gift. I forgave because I wanted to be free of the way old hurts replayed themselves in my chest during anniversaries.

Years later, the brownstone would hear a child’s laughter and the clink of small spoons against bowls. Stephanie would visit—cautious at first, with apologies like flowers that had been tended for weeks—and sometimes the three of us would sit at my mother’s old kitchen table, talking about seedlings and insurance policies, about the small and necessary ordinary things that build a life. Nathan’s name grew quieter in our mouths over time. He was a ghost in photo albums and a cautionary note in conversations about hubris. Stephanie rebuilt herself into something steadier—less show, more substance. She learned to quiet the performance she’d always polished for audiences and, in its place, to build a life modestly earned.

At my mother’s grave, the first spring after her death, I stood with Zachary and a small bouquet. The wind smelled like thawed earth and rain. Stephanie came, wearing no diamonds, hands folded. She touched the cold stone with the gentleness of someone learning how to care for things again.

“I’m sorry,” she said simply.

“I know,” I told her. And I meant it.

The story that the world liked to tell—of the sister who stole the fiancé and the woman who was left—never captured the truth. Life isn’t a headline. It’s a long sequence of decisions, many of them messy, many of them redemptive in ways that only show up with time. The ring that had once meant everything proved, in the end, only a promise of one chapter.

“What did you want me to learn?” I asked my mother the first night I slept in my new apartment, years earlier, when grief felt fresh and sharp.

Her answer unfolded like tea steam in my memory. “That people can break you,” she’d said, “and you can still put the pieces together. Not for them. For you.”

I married a man who helped me assemble a more honest life—one that honored the small rituals my mother taught: the blue dress, the note in a lunchbox, someone who showed up. I loved him because he loved me, not because of any prize he could buy. And when my sister walked into that funeral flashing a ring, the world saw a spectacle. But I had already found the quiet, patient scaffolding of a different joy.

Years later, I would tell this story to my child as we packed a picnic for the park—less to explain the hurt and more to explain the way light returns. “Sometimes,” I would say, “people will hurt you in ways that break your heart wide open. Sometimes they will be the storm. And sometimes even storms, in their passing, teach you where to plant better seeds.”

The funeral had been a threshold, a strange and appointed turning point. There, under the solemn roof and later under the gray rain, my sister’s face had gone pale for reasons she had not expected: not because she had been exposed in front of our community, but because the woman she had underestimated—myself—stood beside a man whose hand she did not hold. In the space between the old life and the new, the truth finally fit into place: what she had taken had already moved on, not because I chased it, but because it never defined me.

And when I spoke at my mother’s memorial, about the cups she kept for Sunday and the patience she taught, I also spoke about the quiet miracle of rebuilding. People applauded then, softly. As the crowd thinned and the pallbearers took the casket away, my sister and I stood together, a small, imperfect bridge between our younger selves and the ones we had become.

“Try,” my mother had said. I had tried. And in trying, I found the life I was meant to live—a life that fit, at last, like a well-worn dress: comfortable, honest, and mine.

News

After my father passed away, my sister seized the house without a second thought, leaving me with nothing but his worn-out wristwatch. Only days after the funeral, she stuffed my belongings into a suitcase and forced me out. With nowhere to turn and fear tightening my chest, I called our family lawyer. I expected comfort, but instead he chuckled dryly. “I knew this would happen,” he said. “Your father saw it all coming. Come to my office tomorrow—what he left you will change everything.”

I stood on the cracked walkway of my father’s old house in Madison, Wisconsin, clutching his battered wristwatch like a…

My sister slapped me across the face during her $20,000 wedding dress fitting — the one I was paying for with my combat pay. “You’re ruining my moment,” she spat. So I walked out, took out my phone, and canceled the credit card that funded her entire $500,000 wedding. Outside, I leaned against the wall and watched her perfect fairy tale start to crumble.

The sound cracked across the boutique like a whip. For a moment, everyone froze — the stylists, the consultant, even…

Devoted husband cared for his paralyzed wife for 5 years — but the day he forgot his wallet and returned home early, what he saw left him frozen.

Michael Turner had always considered himself a lucky man. In his early forties, with a stable job as an architect…

My Mom “Forgot” A Plate For My Daughter At Christmas — Said There “Wasn’t Enough” Because She Upset

My mom forgot a plate for my daughter at Christmas, saying there wasn’t enough because she had upset the golden…

Poor Orphan Forced To Marry A Beggar, 2 Weeks Later They Returned In A Private Jet

As the laughter grew louder, Dakes turned slowly, dripping, broken, humiliated, and the weight of shame pressed heavy on his…

“I Just Wanted to Check My Balance — The Millionaire Laughed… Until He Saw the Screen”

They took him to the VIP floor with the courtesy of people who have never learned how to be unkind…

End of content

No more pages to load