Rumor is a net that gathers whatever drops from the busy sky. Josiah Brennan, a hunter whose name belonged in the same breath as the Soto and Wheeler expeditions, held Whitmore’s offerings up to his lamp and said what his years taught him: these were not animals of the local slopes. Brennan’s disdain for the impossible folded into a quiet, scornful fear. If Whitmore’s hides came from creatures out of place, that might be the least of the valley’s problems.

Then the dreams began.

People who used Whitmore’s hides in ordinary ways—draped over beds, stretched across walls, fashioned into throws for the infirm—found themselves waking with vivid memories of corridors carved from living rock and light that cast no shadow. In those visions there were gatherings, hands and faces moving to a pattern that was not musical, not language, something older and stranger. The dreams were persistent; they played again and again like a song stuck in a head. It started as a handful of reports—Ingred Kesler’s recounting to her sister in Denver of being watched by eyes that moved through the trees—but in time the hub of stories widened, until the priest, Father Cornelius Ashford, tucked between parish duties and letters to the diocese, started to compile interviews.

Father Ashford, for all his theological training, had been a careful student of natural history while at seminary. He did not leap to supernatural conclusions. His notes, meant for no one but himself, were the kind a rational shepherd writes when lambs go missing: precise, careful, concerned. He found consistencies across households. Those who had the hides in contact with their skin or close to their sleeping places reported not only similar dreams but a steady, unaccountable withdrawal from the rest of the valley. People who once tended church and harvest now sat staring at the far slope, their conversations growing spare and rehearsed. Children woke from sleep and hummed fragments of melody in languages neither parent had taught them. The first disappearances came quietly; thin threads severed: a couple gone with no sign of struggle, a root cellar sealed as if to hide only provisions, a cabin bed made as neat as a promise but the hearth cold. Yet no footprints marked the snow beyond their threshold.

When the Hendersons vanished, that disappearance pried open the valley’s closed lid. John and Martha Henderson were regular customers of Whitmore’s; their cabin gleamed with pelts that made their hearth look prosperous. They were last seen buying extra flour and candles, items destined for a family not planning to travel. No tracks led away from their door through the fresh drifts; the horse in the barn pawed and nickered but bore no rider. In the root cellar the searchers found the hides hidden beneath preserved turnips and quart jars: sewn into garments, marked with geometric scars so precise they looked ceremonial. Dr. Thorne took them back to the light and to his instruments. Under the microscope the marks showed themselves as healed wounds—injuries made and allowed to knit—arranged in mathematical arrays. The seams hid under fur so expertly that only a trained eye would catch them, and yet there were signs the pieces had been tailored for particular bodies.

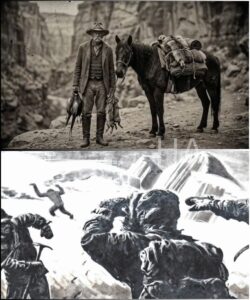

There are moments at which a community remembers its origin—that it is composed of people who must act together to survive. Creststone’s men gathered. They told Whitmore he was no longer welcome. He did not plead. He smiled, and in that smile there was a quiet that had nothing to do with kindness. He said, almost gently, that the arrangement had served its purpose. “Your people are ready for the next phase,” he said. He spoke of the “worn gifts” in a tone that meant the phrase was a key. Whitmore left for Dead Horse Canyon and the trading cabin where Jeremiah Slom had once taken refuge. When the town posted guards at the road and forbade the man from stepping into Creststone again, Whitmore tightened his pack, mounted his bay gelding, and rode until the pines swallowed him.

This is where the valley’s few remaining rational men—Dr. Thorne and Father Ashford prominent among them—took their stand. They could not know whether Whitmore had been an agent acting alone or the outward arm of an interest much older and more networked. Then, when a party went to search Dead Horse Canyon, the terrible craftsmanship of the trader’s work became plain. The cabin was older than Whitmore’s tenure suggested. On its walls and rafters were the same mathematical carvings that slumbered under fur and under healed flesh. Inside, garments hung from rafters, half-finished, some the size of men, some the size of children, all sewn with the same precision. A crude map painted on a wall showed points and lines not only across Colorado but between far places: symbols of a language that was more design than dialect. In a crawlspace under the floorboards the priest found letters—clinical in nature—discussing “subjects,” “adaptation rates,” and recommendations to move to “final phase” during migration times so missing persons might be explained as natural causes. Men who signed the letters had titles and initials—M. Fletcher among them—that suggested more than frontier larceny. The enterprise, whatever it was, had age, voice, and methods.

The people tried to fight what they could. They burned the hides and tried to set fire to the cabin. The smoke burned blue and strange; the fire would not catch easily, and when it finally took, the smoke made patterns that clung to the air like stitched ghosts. The shapes were familiar to those who had seen the carved panels: geometric, ordered, meaningful. Men wept because there was nothing else to do but watch. Their protests to the territorial marshall in Alamosa yielded a report that summarized the events as ordinary misadventure: people leaving because of weather, a settlement shrinking for economic reasons. The marshall’s words were cautious, and Washington’s bureaucratic machinery, slow even at its best, made the valley’s harm into a footnote.

Winter loosened its hold, and the empty houses gradually began to collapse inward. Yet the marks remained. Hunters months later still found deer and small animals with healed scars—geometries etched into bone and hide that could not be explained by accident. Surveys later, in the 1920s, found cave mouths under Dead Horse Canyon opening into chambers expanded with care, their walls not only tunneled but smoothed and intentionally patterned. Men who entered those chambers returned changed, or did not return at all. Reports of footprints that ended in smooth stone, of tools left beside a pool and then no human hand seen again, added to the archive of unease.

But there is a particular cruelty to mysteries that leave traces of intention: they imply somebody went before, planned, and perhaps continues to plan. And plan they did. The letters hidden beneath the floorboards—documented by Father Ashford and later in Dr. Thorne’s private correspondence—read not like the notes of a band of thieves but like the minutes of a systematic program. The vocabulary spoke clinical observation: specimens exhibiting “expected behavioral changes” within specific timetables. The author recommended timing “final phase” to coincide with migrations so the phenomena could be ascribed to natural loss. Reading those words, Dr. Thorne wrote darkly to a friend in Denver: the operation has knowledge of healing stages and of anatomy beyond the usual; they treat animals and people as material for a broader pattern.

When the valley emptied, the last letter left by Evangelene Kesler was found folded in a private drawer, a thing too human to be catalogued with maps and specimens. She wrote to her sister-in-law as though recording to a log book to be kept against calamity; the letter was hasty, line-crossed and rewritten. She wrote of the chambers, of the people who had vanished and who now seemed content in places below the rock. She wrote that these friends were “doing work” beneath the earth—work she could not explain but which, terrifyingly, she did not wish to leave. Her ledger, typically full of numbers and oil and salt, ended in patterns—geometric coordinates reported like prayer. She had been converted, perhaps; she had been invited, perhaps; enough had been taken from her that she saw the invitation as the inevitable answer, and she had written the letter as a way to tie a thread back to the world she had known.

Unknowns breed authorities. Men in positions of influence—miners, surveyors, the state’s agents—tried at different times to open the canyon further, to map routes, to mine veins. Invariably those expeditions stalled, their reports edited, their maps blacked out. A mining survey in 1923 stopped after two men failed to return from a night reconnaissance in the caves. Harrison Webb, the survey leader, left notes in a private ledger later discovered among company papers. He described sudden compulsion in men who had been stern and solid as oak: a tendency to walk in patterns near the cave mouths, eyes glassy with intent. Dynamite was used to seal specific passages, but explosions only collapsed sentinel levels; deeper galleries persisted, whispering after the blasts like distant machinery.

Years later, a psychiatrist named Malcolm Strickland tried to make sense of the valley’s neurochemistry in the tidy language of his field. He argued that mass psychogenic illness could explain certain features, especially the dreams and the shared compulsions. He published a paper on group suggestibility and rural isolation; his public thesis placed the cause squarely within the human mind’s capacity to share narratives and hallucinations under duress. Yet his private notes, found after his death, told of a panic that struck his own team as they investigated a cave mouth: instruments showed anomalous readings when near the carved stones, and two of his crew left to explore deeper and did not return, leaving a lantern burning where they had stood. He crossed his notes out with a hand that trembled; what he had written to himself threatened his reputation and his career, and so he published a different sort of paper. The canyon’s memory existed, then, as both evidence and a scandal to be managed.

If there was design behind Whitmore’s work, what was the end? That is the question historians and folklorists and a handful of determined investigators kept returning to like seasonal migrants. The artifacts suggested that someone, sometime long ago, had known how to shape small creatures and human attention toward ritualized behavior. The pattern of geometric scars, precise seams, and the maps that connected points like star charts were not random. They were an architecture of compulsion, a language in which objects—hides sewn with intention—could be invitations. Wear the garment; you are transformed not only in body but in aim.

There is a human tendency to make enemies of the unknown. The valley’s people, draped in fear and grief, lit fires and burned what they could. They petitioned the territorial government, only to be summarized away in a clerk’s ledger. The very remoteness that had once been a protection—shelter from town politics and the reach of law—had become a vulnerability, a place where experiments could be conducted without witnesses larger than the small community.

And yet, in the marrow of this story, in the things that make it not merely a tale to frighten townsfolk but an account of human tragedy, is the question of consent. Whitmore’s hides had not killed people so much as re-house them; his work did not extinguish, it redirected. The Hendersons were not found dead. The missing couples had been stitched into garments and led into places where work—some work—was done. It is a gruesome sort of salvation: to be rearranged into a purpose not of one’s choosing. That idea annoyed Father Ashford into a theological crisis. He found himself asking whether a community’s fate could be altered by offerings that felt like blessings. Could a people be harvested and transformed into something else, something whose existence satisfied another, older order of being? He felt the prayers he had learned fall short against rooms that were lit by a light that cast no shadow.

Yet the truly curious thing, and the thing that complicated the valley’s narrative into something resembling human horror rather than supernatural malice, was the curious manner in which those who were taken sometimes seemed content afterward. Evangelene, in her last letter, did not beg for rescue. She described singing in a tongue she did not know, making patterns on walls the way a seamstress traces cloth. In that contentment was a quiet that cut the men who loved her: how to mourn someone who had not suffered in the way people expected to be mourned? In the priest’s journal there are paragraphs where grief tastes like resignation because the absent were reported to be in a place where they were no longer lonely. One might imagine the men under the stone simply busy, occupied with tasks whose meaning was not given to the surface—like a wave’s undertow pulling sand from shore toward a hidden reef.

Time moved. The valley emptied in the spring of 1894. Moss took root on unused doorframes; the Kesler ledger, left in the store, grew into a palimpsest of purchases and then geometry. The nation marched on—railroads, mines, new treaties—yet the geometric marks and maps left by Whitmore’s work remained, like a grammar for a language the surface could not read. Scientists came and left. The federal government eventually cordoned the area, the preserve established to prevent unregulated exploitation. Those who entered the preserve in later decades—hikers and curious students—sometimes reported odd things: a trail that the GPS said should be there and wasn’t, a sudden pull toward the canyon like someone tugging the hem of a coat. Devices sometimes failed; people arrived at little clearings with no memory of the turn they had taken. Stories, like old scars, do not erase easily.

What, then, do you do with a mystery that seems older than men but not immune to their hands? Some people answer in stone; they seal the canyon and station the land with law. Others answer with science and try to name the patterns. A few, finding science and law both awkward and blunt, answer with ritual in its human form: a new community arose in the years after the valley’s hollowing, an informal fellowship of those who had not been taken and who had been there and seen what grief does. They kept vigil at the edges: they lit fires and said names, they recorded things in ledgers and drew patterns in the dirt, partly in the old geometric ways that Whitmore had used and partly in songs passed down from the Ute elders who had once called the valley a place where the earth speaks.

Here the story bends, because it is a human thing to seek redemption even out of a wrong. Father Ashford did not abandon his flock to sorrow. He traveled to the neighboring pueblos and met with elders who spoke of the deeper ways of the land. He learned in broken phrases that Dead Horse Canyon had long been a seam between surfaces: the elders spoke of “calling places,” of caverns that needed tending and offerings, of an old reciprocity between those who lived on the surface and those who worked under the stone. He listened; he did not adopt the elders’ speech as his own. He learned enough to change how he prayed. He came to see, with a humility born of sleepless nights and too many dreams, that Whitmore’s operation had misused an old grammar. The trader had not invented the patterns. He had, perhaps, found a way to exploit a human and animal impulse toward pattern and placed, to stitch flesh and geometry into a language that called.

If one believes in the possibility of undoing wrongs, it is necessary to try the right ceremony, the right repair. Father Ashford and Dr. Thorne, with two farmers and a woman from the Keres pueblos who had been trading with the valley years ago, went beyond the canyon’s mouth one late autumn when the snow lay thin. They went not to storm the caverns—language and memory had taught them there was nothing they could do by force—but to make an offering shaped by humility. The woman—no trader, no priest, only a midwife and elder called Ixa—brought with her seed and combed flax; she sang the songs the canyon had not forgotten, threads of melody that asked permission and offered labor in return. The men lit a careful fire and burned no hides. They spoke aloud the names of the missing: Martha and John, Jeremiah Slom, the couples who had left in the cold. They traced patterns in the snow that imitated neither Whitmore’s carvings nor the geometers’ diagrams but instead tried to mimic the earth’s own lines: the arcs a river makes around a stone, the radius a tree’s roots map in dark soil.

It would be romantic to say that the corridor answered, that the missing came back that night, shaking snow from their sleeves and laughing with the foolishness of the living. That did not happen. The caves remained hollow and humming. But something subtle changed. The dreams that had dogged Dr. Thorne loosened their hold; Father Ashford’s sleep returned its old rhythms, if not entirely. Birds returned to the scrub that winter and nested where they had not nested since Whitmore’s tenure. The animals whose hides had once found scarred patterns began, in the years that followed, to appear in the hills with no mark at all—natural and unaltered. It was not a victory so much as a slow, communal breathing out.

It is worth saying that the canyon’s pull did not end. People passing with curious hearts and modern equipment still find GPS traces in their devices that do not match the ground below, and a hiker occasionally discovers a hidden notch in stone where a rope once hung. The preserve officers, the academic papers, the quiet lawsuits of 20th-century investigators have all produced maps with shaded zones and hazard icons. There are places on maps where a line reads: restricted. There are places where the grid refuses to hold.

Creststone Valley’s memory, however, settled into another pattern: human humility and a recognition that some things are not to be possessed. The Kesler ledger was preserved in a museum, but the last pages were reverently sealed. Father Ashford, in a letter decades later found among his papers, told of a ceremony he would not perform again because the canyon had its own calendar. Dr. Thorne died with notebooks full of the microscopic evidence and with a fold of unpublished letters where he confessed that the man who had seen most had also been most susceptible. He had been pulled, he admitted, by an ache to understand. He recorded the things he could measure—the mineral content, the hair structure, the seams—and he left the rest to those with other tools: the songs and cautions of the elders, the quiet watch of the woods.

What remains important, now that these events sit in the dust of history, is not the explanation we demand—whether Whitmore was a grifter who found a language of compulsion, whether he was the operative of a larger experiment, whether the caves themselves had a nature that people could mistake for agency—but the human choices made after the harm. The men who burned hides poisoned themselves with smoke and grief for a stubborn effort to remove what could not be wholly removed. The families who stayed behind learned, painfully, to live with loss and to mark the days with small acts of care. The ones who left carried the story like a cauterized wound; they married and had children, and the story became wrapped in family lore. Some told the tale as a ghost-story proper and added the campfire embellishments that make it taste like fear. Others, less loudly, wrote letters and sung lullabies that numbered and named those who had been taken.

Whitmore himself was never found. Some said he had been swallowed by his own map; others said he moved on to the next valley, the next seam of earth that would offer him a language to work with. Men saw only the fainted track of a bay gelding across the ridge and then the snow smoothed it away. There were handbills posted in towns in later years—old, ragged, the sort of notices that advertise inventions and lost kin. A name was given once in a circulation of rumors—M. Fletcher; another, an urban doctor who wrote clinical notes from afar. None produced a courtroom, and the law, at its best, is as much about evidence as it is about moral accounting. The people whose lives the operation had rearranged remained the moral accounting the law could not reconcile.

The valley, in time, gathered moss and trees again. Goldenrod filled the store window frames. The Kesler ledger, opened by historians a generation later, read more like folklore than record: purchases side by side with geometric lines, as if nothing in life is only one thing at a time. Scholars debated whether the geometric marks indicated some cultural exchange misread by a century’s arrogance, or whether they were the work of a mind we cannot imagine. Anthropologists looked at the Ute oral histories and took seriously what the elders had said all along: that the place could call. That same humility, paring back the sweeping gestures of men who want answers in single phrases, is perhaps the thing the story wants. It asks that we remember how often we raid our own world for meaning and then worry when other meanings answer back.

The final image—the one I prefer to keep—does not belong to Whitmore. It belongs to a woman sitting by the Kesler hearth years after the last of the original households left, rocking a child in whose hair a grey thread glints like winter’s first frost. She draws geometric shapes on the floor without thinking—an old habit, a language of comfort whose original grammar she cannot explain—and hums a tune learned from Father Ashford, who had taken a few lines from the elders’ songs. The child will grow up and perhaps go to school in a town where legends are sold as postcards. Perhaps he will be the sort of man who forgets the cautionary parts of history. But there is a daily kindness in that house: the cooking of a pot, a letter written and folded into a drawer, a promise whispered to the cold that those who had been taken would be kept in memory, not in a plan.

There is room, at the end of this long and strange thing, for two truths. The first is that the world holds patterns we do not command. The second is that the human response—compassion, the building of fires to keep others warm, the recording of ledgers to remember what is spent and what is kept—matters when explanation fails. The men who tried to burn what Whitmore left did so with desperation, a violent attempt to reclaim agency. Those who later offered songs and seeds did something else: they built a cord of community that might, by patience rather than force, bind edges and close wounds.

In the maps that later surveyors drew, the canyon is a blank; in the stories of those who keep vigil it is a seam to be approached with humility. If the pattern Whitmore used ever calls again, the valley’s response will not simply be men with torches. It will be a congregation of song and law and quiet remembrance, a coalition of the village and the elders who taught them to listen. That is the humane ending the valley achieved: not a triumphant reclaiming of all that was taken, but a commitment that those who depart are held in memory and that those who remain will shape the land with a gentler hand.

In the end, the strangest fact is not that strangers can teach us to fear; it is that, in the midst of fear, people sometimes find the better part of themselves. Creststone did not become the place it was before. It never could. Its houses are gone and the maps show a preserve. But among the ribbons of song passed by midwives and the folded ledgers in museums, something endures: the small, stubborn, humane acts of caring for one another, the insistence on naming what was lost, and the willingness to keep watch at a canyon mouth that, in its own way, still listens.

News

End of content

No more pages to load