Miles Carter never imagined he’d be standing on Laurel Harmon’s porch at midnight, weighing two choices that both felt wrong: knock, or turn around and pretend he never saw the porch light burning like a watchful eye.

At twenty-three, Miles lived the kind of life that stayed inside its lanes. He detailed cars for a living in a small shop twenty minutes outside Indianapolis, Indiana, and his house was modest in the specific way a young man’s place can be, with more square footage devoted to tools and polishers than to groceries and plates. He worked long hours rubbing other people’s fingerprints out of their leather interiors, then came home and unwound to playlists no one else liked, songs that sounded like rust and thunder and hope. The rhythm was predictable, and predictability had always felt like safety. He was not looking for a night that would rearrange the meaning of the word “home.”

Then Jace called.

Jace Harmon and Miles had not talked much in months, not since Jace moved to Nashville chasing music and whatever version of himself he believed lived on a stage. They were still tethered by the leftover loyalty of teenage years, the kind built in basements and parking lots and long summers where you swear the world will never separate you. So when Jace’s name lit up Miles’s phone close to midnight, Miles answered with a sinking certainty that the call was not casual. Jace’s voice came tight, rushed, as if he’d been holding his breath for hours. He said he’d been trying to reach his mom all day, that she never ignored him like this, that something felt wrong in his bones. He asked Miles, not as a favor but as a plea, to check on her.

Miles had not seen Laurel in a couple of years. Back then, she had always carried a calm presence that made the chaos around her feel like background noise. She was the kind of woman who could refill a drink, make a joke, and smooth over a tense room without anyone realizing she’d done it. That steadiness made Jace’s panic feel heavier, like a warning bell you couldn’t afford to shrug off. Miles grabbed his keys, pulled on a hoodie, and left without overthinking it, because thinking would have turned into hesitation. The streets were empty in that late-night way that makes even your tires sound too loud, and as he drove, his mind ran faster than the car, inventing terrible reasons for silence.

When he pulled into Laurel’s driveway, the porch light was on, but the windows were dark. No TV flicker, no moving shadows, no small signs of a life continuing on the other side of glass. The stillness did not make a sound, but it pressed against him anyway, the way a room can feel wrong even before you know why. He sat in his car for a moment, hands on the steering wheel, remembering the last time he’d climbed these steps as a teenager, when sneaking in after curfew felt like rebellion and the world still held room for apologies. The wooden steps creaked when he crossed the walkway, familiar and strangely comforting, as if the house was the same even if the people inside might not be.

He raised his hand to knock, but the motion stalled.

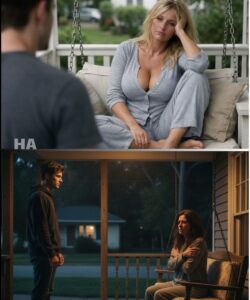

Laurel was sitting on the porch swing.

She wore pajama pants and a thin sweatshirt, no shoes, arms folded tight around herself as if she was holding her ribs together. Her eyes were red, not the fresh red of tears in progress, but the rubbed-raw red of someone who had cried until the crying stopped and the pain kept going anyway. Her hands trembled slightly, not enough to look fragile, but enough to look human. Miles stood there caught between awkwardness and concern, between the instinct to ask questions and the instinct to simply be present. Laurel looked up slowly, as if lifting her gaze cost energy she didn’t have, and she offered a small smile that was more effort than joy.

“Miles,” she said, voice barely above a whisper, like she was surprised her throat still worked.

“Jace is worried,” Miles replied, stepping closer but not too close. “He’s been calling.”

Laurel nodded, eyes dropping to the porch floor as if it held answers. She said the phones were inside, and she “just couldn’t.” The words hung there, unfinished, like a sentence she didn’t have the strength to complete. Miles didn’t push. He didn’t ask why she’d been out here, or how long she’d been listening to the night. He let the quiet do some of the work, because sometimes questions can feel like hands on bruises. The porch light hummed softly above them, and the darkness beyond the yard looked thick, the kind of dark that swallows headlights and returns nothing.

Then Laurel spoke again, sudden and cracked, like dry wood splitting.

“My husband left,” she said. “He packed his things and left. Said he found someone younger. Prettier.”

The swing creaked as she shifted, and her gaze darted toward the driveway as if she was watching for headlights that weren’t coming back. The moment carried a weight Miles could feel in his chest: this was not just heartbreak, it was the collapse of a whole structure she’d been living inside. Laurel stared into the yard and kept talking in short, honest pieces, the way you do when you’re too tired to shape your pain into something polite. The house felt like it belonged to someone else now, she said. The bed felt like a place she couldn’t breathe. Her life, carefully managed and scheduled, had been emptied in a single evening like a drawer dumped onto the floor.

Miles lowered himself onto the porch railing a few feet away, giving her space without leaving her alone. He could have offered clichés, could have tried to build a quick bridge over her grief, but he knew grief didn’t cross that way. Instead, he stayed still, letting his presence be the only promise he made. Laurel’s eyes shifted to him, and in them he saw something searching, as if she was reaching out without moving. When she spoke again, her voice was quiet, shaky, and it surprised even her.

“Take me anywhere,” she said. “Just… anywhere.”

Miles did not ask what she meant. He understood that she was not asking for a vacation, or a thrill, or a plan. She was asking not to drown in the place where everything had broken. He nodded once, like the decision had already been made the moment he answered Jace’s call. Laurel stood up without packing anything, without grabbing a purse or a jacket, and walked to the passenger seat like they were going for a late-night burger run instead of driving away from the ruins of her marriage. Miles started the car gently, as if loud movement might shatter her into pieces.

They left the porch light behind.

Miles drove toward Geist Reservoir, not because it held some grand meaning, but because it didn’t. It was close enough to feel spontaneous, far enough to feel like an escape, and he remembered Jace mentioning once that his mom liked the water, that she used to sit near it when she needed space. The road unwound in quiet stretches, and Laurel sat with her window half down, letting the cold air brush her face like it might wake her from a nightmare. She looked out as if the world had turned grayscale, every streetlight muted, every sign too ordinary for what she was carrying. Miles kept both hands on the wheel, listening to the silence between them and respecting it.

When they pulled into the overlook, the lot was mostly empty. A dim streetlight barely reached the edge of the black water, and the reservoir absorbed the moon as if it had been made for swallowing light. Miles parked and turned the engine off, and they sat without speaking for a while, watching the kind of quiet that doesn’t ask for commentary. The air smelled damp, and somewhere in the distance a frog called, small and stubborn. Laurel finally spoke, her voice softer now, almost surprised.

“You brought me here once,” she said.

Miles glanced over. Her face was turned toward the water, but her words were present, not drifting into the past so much as holding it in her hands. She told him it had been years ago after one of her first big fights with her husband, Grant. Jace had been at a sleepover, and Miles, seventeen and borrowing his dad’s old truck, had knocked on the door because he needed to drop something off for Jace. Laurel had been crying, and she’d insisted she was fine. Miles had answered, clumsy but sincere, that people who say “I’m fine” usually aren’t, and then he’d offered to drive her somewhere just to breathe. She remembered that, she said, as if it had been a small kindness that had secretly mattered.

“He promised things would be different after that night,” Laurel murmured. “He said he’d try harder. He said he’d see me again.”

Miles didn’t pretend to have the right words, because the right words are rare and often silent. He nodded slowly, letting her feel heard without trying to edit her story into something easier. Laurel leaned back, head against the seat, hands still folded in her lap like she didn’t know where else to put them. She said she felt like a fool, like she’d been holding onto a version of her marriage that only existed in her imagination. Grant hadn’t even flinched when he left, she said, no hesitation, no regret, as if walking away from her was a chore he’d finally finished. She wiped her cheek with the back of her hand without ceremony, like she was tired of caring how sadness looked.

“You mattered,” Miles said quietly.

He did not say it to fix her. He said it because it was true.

Laurel turned her head and looked at him for the first time since they’d left her driveway. The porch-swing woman and the calm mother Jace used to talk about were both in her face at once, and for a moment Miles felt time blur. She wasn’t just Jace’s mom, or a name he’d heard while eating pizza in a basement, or a person who belonged neatly in someone else’s family. She was a whole human being who had been carrying too much for too long, and now the straps had snapped.

“Thank you,” she whispered.

They stayed by the water until the cold crept into their bones, and when Miles asked if she was hungry, Laurel shook her head, then paused, as if her body didn’t know what it needed anymore. She said she couldn’t tell if she wanted a burger or if she just wanted to feel normal. Miles found a twenty-four-hour diner on his phone, but before he could suggest it, Laurel touched his arm lightly, fingertips only, like she was asking permission to be honest.

“I don’t want to go home tonight,” she said. “I can’t sit in that bed. Not yet.”

Miles nodded once. “Okay.”

He drove them to a low-rise roadside motel a few miles out, one of those older places with a flickering vacancy sign and zero pretense. At the front desk, the clerk barely glanced up from a tiny TV. Miles asked for a room with two beds, slid over his ID, signed the receipt, and accepted a key card that still had a strip instead of a chip. He did it all with the quiet competence of someone who understood that dignity matters most when you feel like you’ve lost it. When he opened the car door for Laurel, she stirred as if she’d been underwater, then followed him inside without argument.

The room smelled like fabric softener and something fried, familiar in a way that made it less threatening. Two double beds sat under stiff quilts with geometric patterns, and a small table held a pizza menu promising delivery until 3:00 a.m. Miles turned on the lamp by the window and skipped the overhead light, because the night already felt exposed enough. He ordered food, basic and uncomplicated: a burger and fries for Laurel, a sandwich for himself. Laurel took a few bites, then set the burger down like the act of chewing required too much focus. She said her head was too loud, and Miles told her it was okay, that she could eat what she could and leave the rest.

Later, the rain began, not a storm, just a steady tapping against the window that filled the silence between them. Laurel sat cross-legged on the bed nearest the window, hoodie sleeves pulled over her hands like a habit she couldn’t stop. She asked Miles if he ever thought life could shift so suddenly you didn’t recognize yourself anymore. Miles admitted that he mostly had those thoughts around 3:00 a.m., and Laurel gave a small smile that finally looked like it belonged to her. Miles took the other bed, clothes on, shoes off, and kept a careful distance, not because temptation hummed in the air, but because he refused to be another man who treated her pain like an opening.

At some point in the dark, Laurel turned her head toward him and said, “Thanks for not leaving.”

Miles made a soft sound of acknowledgment, not wanting to break the fragile calm. Eventually they both slept, not deeply, but enough to loosen the tight knots of the night. Morning arrived gray and gentle, rain still falling but lighter now. Miles made coffee from the small motel machine, the kind that tasted like cardboard and effort. Laurel took hers with two sugars, no cream, and when Miles guessed right without asking, she smirked as if the world still held room for small victories.

“You snore,” Laurel said, sipping.

Miles lifted an eyebrow. “That’s a lie.”

“You breathe enthusiastically,” she corrected, and this time she laughed, not loud, but whole, like a door opening somewhere inside her.

When the laughter faded, the hurt remained, but it was quieter, less frantic, as if it had moved from a screaming room into a heavy box. Miles asked what she wanted to do now, and Laurel stared out the window for a long time before admitting she didn’t want to go home yet. Miles nodded and offered something simple: they could just drive, no plan, no destination, just forward. He said it like a suggestion, not a rescue, because rescue can feel like a cage if you’re trying to reclaim your own choices. Laurel agreed with a small nod, and when they checked out closer to noon, it felt less like running away and more like taking one careful breath.

At a gas station a few miles south, Laurel went inside while Miles filled the tank. She returned with two coffees, hers already sweetened the way she liked, his black, plus a bag of trail mix that looked like it had been scooped from the most ordinary shelf. It wasn’t the food that mattered, Miles realized. It was the first moment Laurel made a choice for both of them, stepping out of her fog long enough to offer something. They drove with the windows cracked, cold air keeping them awake but not punishing them. Laurel’s hair blew loose, and her smile formed slowly, as if it had to remember the shape.

“It feels good not knowing where we’re going,” Laurel said.

“Yeah,” Miles answered. “Feels overdue.”

They passed a sign for Brown County State Park, and Miles turned without asking. The decision felt right in his bones, the way certain places can. The road narrowed into dense trees, wet leaves and fog hugging the asphalt. The air smelled like damp earth and pine, and Miles felt something in his chest unclench. They parked near a trailhead, grabbed their coffees and the trail mix, and started walking. The ground was soft from the rain but not muddy, and the woods held them with the quiet patience of something that had seen every kind of human grief and never flinched.

They didn’t talk much at first, and they didn’t have to. They passed a couple holding hands, a father with a child on his shoulders, and those small scenes didn’t stab Laurel the way Miles expected. Instead, she watched them like someone studying a language she used to speak. At an overlook, the trees broke open into a view of rolling hills, mist rising like breath. Laurel stood at the edge with her hands in her pockets and said, without turning around, that she hadn’t felt like herself in years. She wasn’t sure she even knew who “herself” was anymore. Miles stayed a few feet back, letting her claim the space, because he could feel how important it was that she didn’t have to perform composure for anyone.

Laurel sat on a damp wooden bench, and Miles joined her, close enough to share warmth, far enough to avoid pressure. She told him she used to be funny, that she used to be the person at the party making everyone laugh, not the mom, not the wife, just Laurel. Then she admitted that Grant stopped seeing her a long time ago, not in one dramatic betrayal but in the slow erosion of being treated like a list of tasks. Groceries. Dry cleaning. Dinner. Polite smiles at work events. A life reduced to maintenance. Miles didn’t interrupt. He understood, in that moment, that being listened to without correction can feel like oxygen.

“You’re easy to be around,” Laurel said suddenly.

Miles shrugged. “I don’t try too hard.”

“That helps,” Laurel murmured, and she exhaled as if her breath had been trapped in her chest for days.

They found a small lodge nearby that evening, rustic and quiet, with pinewood walls and quilts and a front desk that still used physical keys. The clerk looked from Miles to Laurel and smiled like she’d seen weary people arrive carrying invisible luggage, but she didn’t comment. She simply handed them a key and mentioned the fireplace worked well if they needed it, as if warmth was a normal request, as if the world still made sense. In their room, Miles lit the fireplace while Laurel changed into leggings and a hoodie, and when she emerged her face looked less guarded, like the woods had softened her edges.

Dinner came from a local place, pasta and garlic bread eaten on the edge of normalcy. A delivery guy made a joking comment about a romantic getaway, and Miles gave a half-laugh without feeding the idea. They weren’t here for romance, Miles reminded himself. They were here because two people had collided with the same storm and decided, briefly, not to stand alone in it. Laurel found a deck of cards in the drawer, and they played a ridiculous game that made them laugh more than it deserved. Laurel cheated just enough to keep it interesting, then claimed she was testing Miles’s attention span. Miles accused her of being a menace, and Laurel’s grin looked like a piece of her old self returning from exile.

Later, sitting by the window with the fire low, Laurel turned to him with a careful seriousness. She told him he had always been kind, even as a teenager, with a stillness that made other people feel safe. Then she said something that landed like a stone in water: he made her feel like she still mattered. Miles felt the words move through him, heavy with responsibility, because he knew how easily kindness can be misunderstood, and how fragile Laurel’s heart was right now. He didn’t answer fast. He let the truth sit between them, letting Laurel feel it without turning it into a promise.

The moment shifted quietly, not with dramatic music or sweeping gestures, but with the simplest human gravity. Laurel’s eyes met Miles’s and held longer than they ever had. Miles noticed her breathing first, warm and close, steadying. When she leaned in, the kiss was soft and careful, like a question rather than a claim. Miles kissed her back because he wanted to meet her where she was, not because he believed it meant something it didn’t. When they pulled apart, neither of them spoke. The fire popped once, a small sound in a room full of consequences.

They shared a bed that night, not out of heat or reckless loneliness, but out of the need to be near someone who saw you as a person and not a function. Miles stayed aware of every boundary, every pause, every chance to turn away if Laurel changed her mind. He held her the way you hold someone who has been dropped by the world, careful not to squeeze too tight. Laurel’s hand rested against his chest, her fingers curled as if she was anchoring herself. The comfort felt real, and that reality was both tender and dangerous, because real things have weight. Before sleep took them, Laurel whispered that she didn’t want to pretend this was forever. Miles agreed, honest enough to protect them both, and in that honesty there was a kind of respect that felt rarer than romance.

Morning came crisp and quiet, sunlight filtering through pine branches outside their window. They drank coffee on the small porch wrapped in blankets, listening to birds and wind and the simple fact that the world kept going. Laurel asked if Miles regretted anything, her voice steady but cautious, and Miles said no because regret would have turned their kindness into shame. Laurel admitted she didn’t regret it either, but she was surprised she felt okay, surprised that warmth didn’t automatically come with punishment. They stayed one more day, wandering to a small waterfall where Laurel stepped into the cold water with her jeans rolled up and laughed like a kid startled by joy. The sound hit Miles like relief, proof that grief does not erase the ability to laugh, it just makes laughter feel like a victory.

That evening, back in their lodge room, Laurel’s phone finally buzzed.

She stared at the screen as if it might bite her. The name wasn’t Jace. It was Grant.

For a moment, Laurel’s face closed, old fear sliding into place like armor. Miles watched her throat move as she swallowed. The message was short and sharp, the kind of cruelty that pretends to be practical: Grant wanted to “talk,” wanted to “figure out logistics,” wanted Laurel to “be reasonable.” Reasonable, Miles understood, often means “quiet and compliant.” Laurel didn’t cry. She didn’t panic. She stared at the phone, then set it down and whispered, almost to herself, “He thinks he still gets to direct the story.”

Miles felt anger flare, but he kept it contained, because Laurel needed steadiness, not someone else’s rage. He asked what she wanted to do, emphasizing the word wanted, and Laurel inhaled slowly. She said she wanted to go home tomorrow and stand in her own house like she belonged there. She wanted to call Jace and tell him she was okay, not because she was fixed, but because she was alive. She wanted to stop living on the porch swing of someone else’s choices. The decision seemed to straighten her spine, like choosing herself added structure back into her bones.

They packed in the morning with slow care, folding quilts, checking drawers, stretching time because leaving felt like letting go of a spell. At the front desk, the clerk smiled kindly, the way people do when they recognize tired eyes. The drive back toward Indianapolis was quiet, but it wasn’t the tight silence of crisis anymore. It felt more like reverence, like they were carrying something fragile between them. Somewhere on the highway, Laurel reached over and rested her hand on Miles’s for a few minutes, not to start something new, but to say, without words, that she remembered what it felt like to be seen.

When they pulled into Laurel’s driveway, the porch looked the same, but Laurel looked at it differently. She walked up the steps slowly, unlocked the door, and stepped inside as if she was entering a place she had to reclaim. The house was unchanged: framed photos, shoes by the entryway, the quiet scent of someone else’s cologne lingering like an insult. Laurel moved through each room touching small things, straightening a picture frame, brushing her fingers along the couch, as if reminding herself that her life belonged to her, even if it had been hurt.

In the kitchen, Laurel leaned against the counter and finally said what had been forming for hours.

“This place isn’t broken,” she murmured. “It just doesn’t know who lives in it anymore.”

Miles stood in the doorway, letting her have the center of the room, letting her be the main character of her own return. Laurel turned to him with eyes that were tired but clear. She told him he helped her feel alive again, and that wasn’t nothing. Then she said she needed to stand on her own now, to figure out who she was in this house, in this life, alone. Miles nodded because he understood that clinging to comfort can become another prison. He didn’t bargain. He didn’t ask for anything. He simply told her he got it, and he meant it.

Laurel hugged him, longer than polite and firmer than casual. She kissed his cheek, a final softness, and thanked him again. Miles walked out into the afternoon light and didn’t look back, not because he didn’t care, but because he respected the boundary Laurel had drawn for her own survival.

A week passed, and Miles returned to his routines: polishing cars, buffing out scratches, cleaning cup holders filled with the crumbs of other people’s lives. Nothing changed on the outside. The shop still smelled like wax and engine heat, and his playlists still sounded like private weather. But something inside him had shifted, like a door he hadn’t known was locked had quietly opened. On Thursday, Jace texted him a simple message: Thanks for checking on her. She seems steadier. I don’t know what you said or did, but thanks, man. Miles stared at the words for a long moment before typing back: She just needed to be heard.

Two days later, a letter arrived in a plain envelope, Miles’s name written in familiar cursive, no return address. Inside was a single sheet of note paper, folded twice. Laurel wrote that she hadn’t planned to write, but then she remembered how Miles made space for her without asking for anything in return. She wrote that he reminded her she was still a woman, not just a left-behind version of someone’s past. She wrote: That mattered. You mattered. Thank you. Miles read it twice, folded it carefully, and placed it in the top drawer of his nightstand the way you keep a chapter that meant something, even when you know it isn’t where the story ends.

After that, Miles stopped trying to define what the weekend had been. It was not a love story, not the kind that ends in shared leases or wedding toasts. It was a human story, one about showing up when it would have been easier not to, about choosing presence over performance. Laurel did not become a haunting in his thoughts; she became a warm light he’d passed through, a reminder that sometimes the bravest thing you can do is simply not run when someone’s world gets heavy. When Miles drove past the reservoir, he sometimes glanced toward the overlook. When it rained, he remembered the tapping on the motel window. And when a customer thanked him for something small, he heard Laurel’s voice in the back of his mind: You make me feel like I still matter.

Miles didn’t go looking for something to carry away from that night. He carried it anyway.

Not the kiss, not the bed, not even the way Laurel’s hand had rested on his. What he carried was the truth that you can be someone’s steady place in a storm without owning the storm or the person inside it. You can offer warmth without turning it into a contract. You can help without demanding the next chapter. That became the quiet rule Miles lived by afterward, and it made him show up better, not just for others, but for himself. Some stories do not end cleanly. This one didn’t. But it ended honestly, and sometimes honesty is the most human kind of mercy.

THE END

News

‘I Can Fix This,’ the Boy Said — The Millionaire Laughed… Until the Unthinkable Happened

Robert Mitchell hadn’t been surprised by anything in years. Surprise was for people who still believed life could turn left…

They Insulted a Poor Janitor — Next Day He Was Revealed as the Company’s CEO!

New York City had a way of making people feel like punctuation. Commas in crowds. Periods at crosswalks. Exclamation marks…

Undercover Billionaire Orders Steak Black Waitress whispered to Him a something That Stops Him Cold

The crystal chandeliers of Lauron’s cast honey-colored light across starched white tablecloths and polished silverware so bright it looked like…

You’re not blind, it’s your wife who puts something in your food… the girl said to the millionaire

The millionaire had always believed danger arrived loudly. A hostile takeover. A lawsuit with sharp teeth. A rival with a…

Disabled millionaire was Ignored on a Wedding day… until the Maid’s daughter gesture changed everyth

The grand ballroom of the Bellamy Estate glittered like it had been built to impress strangers. Crystal chandeliers poured light…

The Maid’s Toddler Kept Following the Billionaire — The Reason Will Break Your Heart

Adrienne Westbrook’s life was engineered to look untouchable. From the street, his penthouse tower rose over Manhattan like a polished…

End of content

No more pages to load