Thomas stared at his wife as if she had spoken in a foreign language. “A picture,” he repeated, not questioning the logic so much as trying to understand the need. His voice cracked on the last word, and he looked away as if ashamed that grief had found its way through him.

Lillian did not argue, because she understood that Thomas’s silence was not refusal but fear. If they made the photograph, then they would be admitting that Eliza would never sit for one while alive again. If they did not make it, then they would be surrendering her face to the unreliable realm of memory, where even the brightest image could blur at the edges over time.

“I don’t want to forget her,” Lillian said, and the truth of it was so plain that it did not require embellishment. “I don’t want the world to forget what she looked like.”

Thomas swallowed hard, his Adam’s apple moving like a man trying to swallow a stone. He had carried his daughter on his shoulders during Fourth of July parades, had held her hand at the edge of the mineshaft when she begged to see where he worked, had promised her—carelessly, because fathers promised things carelessly—that he would always be there. Now the promise lay in pieces around him, and Lillian was offering him a different kind of vow: that at least the shape of Eliza’s face would remain.

They borrowed coins. Thomas went next door and asked Mr. DeWitt, the shopkeeper, for an advance on the week’s credit. He spoke with the flat tone of a man reciting a list, because if he let emotion into his voice, it might break him. Mr. DeWitt did not ask questions, and in that small mercy there was relief. By noon, the money sat on the table beside a cracked teacup Eliza had chipped months earlier and refused to throw away because she insisted it “still worked just fine.”

The photographer arrived in the early afternoon, before the house had entirely absorbed the truth of its new silence. His name was Gideon Hale, and he was not the sort of man most people expected when they heard the word photographer. He was not young, though not old either, with a face lined by sun and wind rather than age. He moved with the practiced caution of someone who had learned that a camera could make people feel exposed, and he spoke softly, not out of saintliness but out of respect for the room he had entered.

He carried a wooden case that held the camera like a small coffin of polished walnut. Over his shoulder was a cloth bundle containing glass plates and bottles whose labels were smudged from travel. When he stepped inside, he paused at the threshold, as if waiting for permission not only from the living but from the dead.

“I’m sorry for your loss,” he said, and then, because empty condolences felt useless, he added, “I will do this carefully.”

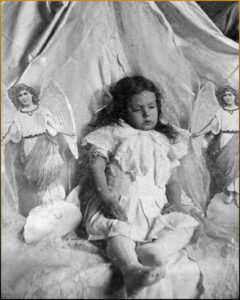

Thomas nodded once, unable to answer without betraying the rawness under his ribs. Lillian led Gideon into the parlor where Eliza had been placed upright in a high-backed chair. The choice was deliberate. Lillian could not bear the sight of her daughter lying down as if already claimed by the earth. Upright, hands folded just so, boots polished, Eliza resembled a child who had been told to sit still for church, and in that resemblance Lillian found a cruel comfort.

Gideon did not flinch, and Thomas noticed that as if it were an act of courage. Gideon set his case on the floor and opened it with slow movements that seemed almost ceremonial. He drew out the camera, its brass fittings catching the dim light, and he unfolded the tripod. He looked at Eliza with a photographer’s eyes, measuring the fall of light across a face, and then he looked away quickly, as if aware that to stare too long would be to steal something.

“May I adjust her a little?” he asked.

Lillian’s fingers tightened around the edge of her apron. “Yes,” she managed, though the word felt like surrender.

Gideon stepped close and adjusted the chair by inches, turning it toward the window where the pale afternoon light slid through the curtains. He tilted Eliza’s chin the way one might tilt a porcelain doll, with care that bordered on tenderness. Thomas watched, his jaw clenched, fighting a surge of anger that had no good target. It was not Gideon he was angry with, not really; it was the world that had made this scene necessary.

While Gideon prepared, Lillian found herself watching his hands. They were steady hands, hands that had mixed chemicals and handled fragile glass, hands that understood precision. She wondered, in a distant corner of her mind, how many rooms like hers he had entered, how many families he had seen standing just out of frame, holding their breath as if breath could disturb the last remnant of a child.

Gideon set up a small dark tent in the corner of the parlor, a portable space where he could coat a glass plate with collodion and sensitize it in silver nitrate. The process was fussy and demanded speed, because the plate needed to remain wet for exposure. In other circumstances, he might have explained this, might have made conversation to ease tension, but he sensed that the Rowans did not want education; they wanted the impossible, and they wanted it without needing to say so.

As Gideon worked, Thomas noticed a flicker in the man’s expression when he glanced at the chalk marks climbing the doorframe beside the hallway. Eliza’s height had been measured there each season, her father marking dates with a pencil and Eliza insisting she had grown “at least a whole inch,” only to sulk when the line disagreed. The marks remained, stubborn and ordinary, and now they felt like a record carved into the house itself: proof that she had existed, proof that time had moved through her even if it would not move beyond her.

The house held other traces too. A songbook lay open on the piano, a children’s tune with notes penciled in where Eliza had struggled. A small glove sat on the mantle as if waiting for its pair. A tin of peppermint candies, half full, was tucked behind a vase, because Eliza had believed in keeping sweets hidden from “thieves,” which in her mind included her own parents.

Gideon emerged from the dark tent with the glass plate ready, slid it into the camera, and draped the black cloth over his head. His voice came muffled from beneath it. “I will need you to stand back. The exposure will take a few seconds. I’ll tell you when.”

Lillian and Thomas moved to the edge of the doorway. They stood close enough that their shoulders almost touched, not because they sought comfort but because the room had become too large, and proximity was the only way to shrink it. Thomas’s hands curled into fists at his sides. Lillian clasped her own hands so tightly her knuckles blanched.

“Hold still,” Gideon said, and then, because the instruction was absurd, he amended softly, “Just… let the room be quiet.”

The camera demanded patience. It demanded light. It demanded time, that same time which had betrayed them days earlier. Gideon counted under his breath. He removed the lens cap, waited, replaced it, and then stepped out from beneath the cloth. He did not smile in triumph. He did not speak like a man pleased with his work. He simply nodded once, as if acknowledging the gravity of what had been captured.

The shutter’s click was not loud, yet it cut through the parlor like a blade through fabric. Lillian felt her throat tighten. That sound, she realized, had given grief a shape she could carry, a small rectangle of paper that would later sit on the mantel and stare back at them with eyes that no longer blinked.

Gideon packed his equipment with the same careful movements he had used to set it up. Before he left, he hesitated near the doorway and glanced back at Eliza’s still form. His expression held something Lillian could not name. It was not pity, exactly, and not horror. It looked more like recognition, as if he had seen this scene in another room long ago and had never entirely escaped it.

“I’ll bring the finished photograph tomorrow,” Gideon said. “I will make it as clear as I can.”

When he stepped outside into the cold, the air hit him like a reprimand. He walked down the street with his case heavy in his hand, and though the town moved around him with its usual noise, he felt as if he were carrying a kind of silence that did not belong in public. He had learned years ago, after his own sister died of scarlet fever back east, that grief did not fade neatly; it learned to disguise itself, to slip into the corners of ordinary life. Photography had become, for him, both trade and penance. With each plate he coated and each image he fixed, he thought he might be building a wall against forgetting, even though he knew forgetting was not a choice so much as a slow leak.

That night, in his rented room above a saloon that smelled of whiskey and sawdust, Gideon developed the plate. Under the dim glow of a safelight, the face of Eliza Rowan emerged on glass, pale and precise. The curls pinned carefully by her mother framed a forehead that looked too smooth for death. The hands folded in her lap looked as if they might unfold at any moment. Gideon watched the image strengthen, and for a moment he felt the familiar ache in his chest, that tug of something unresolved. He thought of his sister, of the photograph his parents had never been able to afford, of the way her face had become harder to recall year by year until he began to doubt his own memory. He knew, then, why Lillian Rowan had spoken with such firmness. This was not morbidness. This was rebellion against disappearance.

When Gideon delivered the finished photograph the next day, it was mounted in a simple frame, nothing ornate, because the Rowans had paid for clarity rather than decoration. Lillian held it with both hands as if it were fragile as breath. Thomas stood beside her, rigid, watching the paper as if it might accuse him. When Lillian finally lifted her eyes to meet the image, she inhaled sharply, not because it was grotesque, but because it was unbearably familiar. There was Eliza’s face, intact, captured in a way that made time pause. The photograph did not give life back, yet it did something else: it gave shape to love that had nowhere to go.

They placed it on the mantel and did not move it far after that. The frame became part of the room’s geography, like the clock and the lamp and the chipped teacup that still sat on the shelf because Lillian could not bear to discard it. Visitors noticed the photograph and sometimes looked away quickly, embarrassed by their own curiosity. Some whispered later in town, using words like strange and grim and unnatural, because people often labeled what frightened them as improper. The Rowans never answered. Their silence was not defiance so much as devotion. If the photograph was the last place they could meet Eliza’s eyes, then they would stand there, even if others did not understand the stubbornness required to keep love visible.

Winter turned to spring, and Virginia City did what it always did: it kept moving. Mines reopened. Men shouted in the streets. New rumors arrived like fresh dust. The Rowans went through the motions of living because the alternative was to lie down beside their child and refuse to rise, and neither of them could quite do that to the other. Thomas returned to the mine with a ferocity that frightened Lillian. He worked longer shifts, came home with his face streaked black, and sat at the kitchen table staring at his hands as if he could scrub away not dirt but guilt. Lillian resumed teaching at the small schoolhouse, because children still needed arithmetic and spelling, and because being surrounded by living voices was a kind of punishment she did not entirely mind.

Yet the house remained altered. Eliza’s laugh did not return to the yard. The chalk hopscotch faded under rain, but the chalk marks on the doorframe stayed, and sometimes Lillian traced them with her fingertip in the quiet hours, remembering the weight of her daughter leaning into her hip, the smell of hair warmed by sun. Grief did not leave. It rearranged itself. It slipped into teacups and songbooks, into the empty space beside the bed where Eliza’s shoes used to be kicked off carelessly.

One evening, months after the fever, Thomas came home with a small bundle wrapped in cloth. He set it on the table and unwrapped it to reveal the photograph, now protected by an extra layer of fabric and a thin board.

“I took it down,” Lillian said, alarmed, because the mantel without that frame felt like a missing tooth.

“I can’t leave it there,” Thomas replied, his voice rough. “Not when I’m not here.”

He did not explain further, yet Lillian understood. The photograph on the mantel was safe when they were home, but when Thomas went underground, when the earth swallowed him each day and returned him only if it felt merciful, the idea of the photograph sitting unguarded in an empty house felt like temptation to loss. Thomas began carrying it with him, wrapped carefully, tucked in his lunch pail between bread and dried apples. Down in the mine, during breaks, he would unwrap it and look, his lamp light catching the paper’s surface, and for a few minutes the mine’s darkness would be interrupted by the stubborn presence of a child’s face.

Lillian did not scold him, though part of her feared the photograph would be ruined. The greater part of her feared what would happen if it were lost, because the photograph had become a kind of second heartbeat in their home. She understood, too, that Thomas needed the image not as decoration but as evidence. Underground, surrounded by men who joked loudly to keep their fear from being heard, Thomas needed proof that he had once been something other than a man who worked in the dark. He needed to remember that he had been a father.

The town’s economy shifted the way it always did, rising and falling with ore prices and speculation. Some families left. Others arrived. The Rowans stayed, because leaving felt like another form of death, as if by moving they might shake Eliza’s ghost loose from the walls. Yet time had its own way of demanding change. When a small fire broke out on the next block and sent smoke curling through the neighborhood, Lillian realized with a jolt that the photograph was not immortal, that wood and paper could burn as quickly as any body.

After that, she began to plan, not in grand ways but in small acts of protection. She wrapped the photograph at night and placed it in a tin breadbox beside the bed. She memorized where it was, the way she memorized exits in a building, because grief taught her that emergencies arrived without permission. Thomas teased her gently once, asking if she planned to sleep with the whole mantel in a box. She did not laugh. Thomas stopped teasing.

In late summer of 1878, the mine groaned under strain. There were rumors of dangerous pockets, of timbers that needed replacing, of management unwilling to close sections because every closed day meant lost profit. Thomas came home one evening with a cut above his eyebrow and a look in his eyes that made Lillian’s stomach clench.

“A beam slipped,” he said. “No one died.”

He spoke the words quickly, as if speed could prevent the alternative from becoming real. Lillian nodded and pressed a cloth to his wound, and when she went to bed that night, she slept with the photograph in its tin box within reach, her hand resting on the metal lid as if she could feel Eliza through it.

Two weeks later, the disaster came. It did not arrive with trumpet or prophecy. It arrived as a sound, deep and wrong, like the earth clearing its throat. Thomas was underground when the support timbers failed in a section of the shaft. Dust filled the air, thick enough to choke. Men shouted. Lamps swung wildly, throwing frantic shadows. In the chaos, Thomas’s lunch pail was knocked from his hand and skidded across the rock, disappearing into the dust.

The mine became a place of instinct. Thomas crawled, his shoulder scraping stone, his lungs burning. He found an opening, a pocket of air behind a fallen beam where a few men had clustered, eyes wide and mouths covered. Someone was crying. Someone else was praying. Thomas’s mind, strangely, fixed on the lunch pail. Not because he cared about bread, but because inside that metal container, wrapped in cloth, was the photograph. Eliza’s face was down there in the dark with him, and the thought was both comforting and unbearable.

Hours passed in a blur of thirst and fear. Rescue took time because rescue always took time; the earth did not hurry for grieving families. When the men were finally pulled from the shaft, coughing and gray with dust, Thomas emerged with his hands raw and his eyes bloodshot. Lillian was waiting among the gathered wives and mothers, her face strained into a shape that was not quite hope and not quite resignation. When she saw Thomas, she made a sound that was part sob and part laugh, and then she ran to him with a desperation that embarrassed no one, because in Virginia City people understood that relief was not dignified.

Thomas held her, and then, when the shaking eased enough for words, he whispered, “I lost it.”

Lillian did not need him to specify. She knew, immediately, what he meant. The photograph. The tin box by the bed had been empty that morning because Thomas had taken the picture with him, as he always did when the mine felt especially dangerous. Lillian felt a coldness in her chest that was not anger at Thomas but terror at the universe’s cruelty, as if it had not been satisfied with taking the child and now wanted to take the evidence too.

“Maybe it’s—” Thomas began, but his voice broke.

Two days later, when the mine crews went back down to clear debris, a boy named Owen DeWitt, the shopkeeper’s eldest, found Thomas’s lunch pail wedged behind a slab of rock. It was dented and scraped, but intact. He brought it up like treasure. When Thomas opened it with trembling fingers and unwrapped the cloth, the photograph slid out, smudged at the edges, the frame scuffed, yet Eliza’s face remained clear beneath the glass.

Thomas sat on the ground and pressed the photograph to his chest like a man holding a living thing. Lillian knelt beside him, her hands hovering, afraid to touch. Around them, the town’s noise continued, yet in that moment, the world narrowed to a child’s captured gaze and two adults learning, again, how close loss could come.

That near-disappearance changed something in Lillian, though it took months for the shift to become visible. She had been guarding the photograph as if it were Eliza herself, as if paper and glass were the last fragile bridge between the living and the dead. Yet now she began to notice how the photograph shaped their lives not only in quiet, private ways but in the way they moved through the world. When another mother in town lost her infant to croup, she came to Lillian with swollen eyes and asked, in a voice that sounded ashamed, if it was true that the Rowans had had a picture made.

“Yes,” Lillian said.

“Is it… is it terrible?” the woman asked, as if she feared moral judgment.

Lillian thought of Eliza’s face on the mantel, the way it had greeted her each morning with a stillness that somehow kept love from spilling away. “It’s hard,” she admitted. “But it’s not terrible. It’s… honest.”

The woman swallowed. “We don’t have much money,” she said. “My husband says it’s foolish. He says folks will talk.”

“Folks talk anyway,” Lillian replied, and surprised herself with the sharpness of it. “They talked when Eliza was alive, they talk now. Let them. Your baby deserves a face in your hands, not just a name on a stone.”

The woman cried then, not quietly, and Lillian held her. Later, Lillian walked through town to find Gideon Hale, only to learn he had moved on weeks earlier, traveling where work called him. For the first time, Lillian felt a frustration not at fate but at practicality. If photographs mattered this much, why did they have to be rare, expensive, dependent on an itinerant man with chemicals and glass?

That question became a seed. Lillian began reading what she could about health and sanitation, about fevers that tore through children, about the invisible ways death traveled through water and crowded rooms. She spoke to Dr. Clarke with more insistence, asked about boiling water, about cleaning wells, about isolation when illness appeared. Dr. Clarke, surprised to have a woman questioning him with such focus, initially bristled and then, perhaps because he was tired of seeing small bodies carried up the hill, began to answer.

Thomas noticed the change. “You can’t out-argue sickness,” he said one night, not cruelly but with the weary realism of a man who had seen too much.

“I can’t,” Lillian agreed, “but I can refuse to do nothing.”

In the spring of 1879, a stranger arrived at the Rowan doorstep with a baby wrapped in a blanket. The stranger was a young woman with red-rimmed eyes, one of the new widows the mine had produced that season. Her name was Maribel Alvarez, and her husband had died in the collapse, leaving her with a son barely six months old and no family in town. She had heard, she said, that Lillian was kind, and kindness was a commodity widows sought the way miners sought silver.

“I can’t keep him,” Maribel whispered, her voice shaking with shame. “I have no milk left. I have no money. I can’t even buy coal. If I stay, we both die. If I leave, I don’t know where to go.”

Lillian looked at the baby, at the small mouth opening in silent complaint, at the tiny hands grasping the air as if trying to catch hold of something solid. Thomas stood behind her, his expression tense. This was not their grief, not their child, not their responsibility, and yet the baby’s helplessness pressed on them in a way grief recognized.

Lillian’s mind, without permission, supplied Eliza’s face, Eliza’s curls pinned back, Eliza’s hands folded. She imagined that stillness and then looked again at the baby’s squirming life, and something inside her made a decision before she could reason it through.

“Come in,” Lillian said, stepping aside.

Maribel’s shoulders collapsed with relief and despair mingled together. She handed the baby over with hands that trembled as if she were surrendering her own heart. “His name is Mateo,” she said quickly, as if the name might protect him. “Please. Please don’t let him be… just gone.”

Lillian took the baby. Mateo’s weight was warm and startling. He smelled like milk gone sour and wood smoke, like a life that had not yet learned fear. Thomas watched, his jaw working, and Lillian could see the battle behind his eyes: the fear of replacing Eliza, the fear of betraying her, the fear of loving again and losing again.

That night, after Maribel left to catch a stagecoach out of town, Lillian sat at the kitchen table with Mateo asleep in her arms. The photograph on the mantel stared out from the parlor, Eliza’s captured gaze steady and unblinking.

“This isn’t a replacement,” Lillian said softly, as if she needed to convince the air itself. “It’s not a trade. It’s… it’s a continuation.”

Thomas sank into the chair across from her, his elbows on the table, his hands covering his face. “If we love him,” he whispered, voice muffled, “will it mean we loved her less?”

Lillian’s eyes stung. She shifted Mateo carefully and reached across the table to touch Thomas’s wrist. “We didn’t run out of love when she died,” she said. “We ran out of places to put it.”

For weeks, the house adjusted again, this time not to absence but to unfamiliar presence. Mateo cried at night, his small lungs insisting on attention. Lillian learned to mix goat milk and soothe him with gentle rocking. Thomas, stiff at first, began to carry the baby around the yard, showing him sunlight and the shape of trees. He did it with an awkwardness that would have made Eliza laugh, and that thought, instead of stabbing, softened into something like warmth.

Yet the photograph remained, and its presence complicated their new life in ways Lillian did not anticipate. There were mornings when Thomas would pause by the mantel with Mateo on his hip, looking at Eliza’s face as if asking permission. There were nights when Lillian, exhausted by infant care, would glimpse the frame and feel a sudden guilt that made her chest tighten, as if she were committing betrayal by continuing to live.

Then came the evening when Mateo, newly able to sit, crawled across the parlor floor and pulled himself up using the leg of the mantel table. His eyes, wide and curious, fixed on the photograph. He reached up with a sticky hand and patted the frame.

Lillian froze, ready to snatch him away, but Mateo did not yank or throw. He simply pressed his palm against the glass and smiled, toothless and bright.

Thomas, watching from the doorway, let out a breath that sounded like a sob disguised as laughter. “Look at that,” he murmured. “He’s… saying hello.”

Lillian’s throat tightened. She knelt beside Mateo and watched him gaze at Eliza’s face with the simple openness of a child who did not yet understand death. In that moment, Lillian realized something that shifted her own grief. The photograph was not only a meeting place for her and Thomas. It could become a bridge between past and present, a way for Eliza to remain part of the house’s story without forcing the house to remain frozen in the day she died.

Years passed, each one carrying its own weight and its own small mercies. Mateo grew into a boy with dark hair and restless energy, with a habit of asking questions that made adults laugh and sometimes wince. He learned to read at Lillian’s schoolhouse, and he learned to hold a hammer from Thomas, who insisted that if Mateo was to grow up in Virginia City, he should know how to fix what broke. Lillian told Mateo stories about Eliza, not as a sainted ghost but as a real girl who once tried to teach a chicken to dance and who cried when she scraped her knee and who believed, fiercely, that peppermint candies could cure sadness.

Mateo listened with a seriousness that made Lillian’s heart ache. He would look at the photograph and then back at Lillian, as if trying to fit the story into the still face. Sometimes he would ask, “Would she have liked this?” when he showed Lillian a drawing or a carved toy. Lillian would answer honestly, imagining Eliza’s laugh, and those imagined conversations became part of the house’s daily rhythm.

In 1885, when a larger fire swept through a nearby block and threatened the Rowans’ street, Lillian’s old panic returned. Smoke filled the air. People shouted. Buckets were passed hand to hand. Thomas ran to help, his sleeves rolled up, his face set in the grim determination of men who understood that a town built of wood could vanish in an hour.

Inside the house, Lillian’s first instinct was to grab Mateo, who was already wide-eyed and coughing. She lifted him into her arms and moved toward the door, and then her gaze snagged on the mantel where Eliza’s photograph sat in its frame.

For a heartbeat, time slowed into an unbearable choice. The photograph had been the axis of her grief for nearly a decade. It had traveled with them through fear and survival. It had been the place where she met her daughter’s eyes when she needed proof that Eliza had been real. If the fire took it, it would feel like losing Eliza all over again.

Lillian’s feet shifted toward the mantel before her mind could decide. Mateo, heavy in her arms, began to cry, frightened by the smoke and the shouting. His small fingers clutched at her shoulder. Lillian looked down at his face, alive and flushed, his mouth open in urgent need, and suddenly the room rearranged itself in her understanding.

Eliza was not in the frame. Eliza was not in the glass. Eliza was in Lillian’s blood, in her memory, in the way Lillian had learned to mother again. The photograph was a vessel, precious, yes, but not the only vessel. Mateo was breathing. Mateo was here. The living demanded priority, not because the dead mattered less, but because love that refused to act was only decoration.

Lillian tightened her hold on Mateo and ran for the door.

Outside, the heat of the fire pressed against the street like a wild animal. Sparks floated in the air. Neighbors screamed names, calling for children, calling for husbands. Lillian stumbled down the steps and joined the chaos, coughing, eyes stinging. She held Mateo close, his face buried in her neck. Somewhere in the confusion, Thomas found them and grabbed her shoulder, his grip fierce with relief.

“You got him,” he said, voice rough.

“I got him,” Lillian answered, and her voice shook not only from fear but from the sudden, brutal acceptance that they might lose the house, and with it, the photograph.

The fire came close enough that the Rowans could feel its breath, yet it shifted, as fires sometimes did, pulled by wind and chance. By dawn, their street still stood, scorched and smoky but intact. The Rowans returned home with ash on their clothes and exhaustion in their bones. The house smelled like smoke and damp wood. The parlor was a mess, chairs overturned from the rush, curtains torn down by frantic hands.

Lillian stepped inside and went immediately to the mantel. The photograph was still there, slightly askew, its frame dusted with soot, but safe. She touched it lightly, her fingers trembling. Relief washed through her, and then, unexpectedly, so did something else: a quiet shame, not for wanting to save it, but for having almost chosen it over a living child in her arms.

Thomas appeared beside her, also looking at the frame. He did not speak for a long moment. Then he said, softly, “You left it.”

Lillian’s face flushed. “I did,” she admitted, bracing for judgment.

Thomas’s eyes were tired, rimmed red from smoke. He reached out and straightened the frame with careful fingers. “Good,” he said simply.

Lillian stared at him, confused.

Thomas swallowed, and when he spoke again his voice carried the weight of years. “I’ve been holding onto her like she’ll fall away if I loosen my grip,” he said. “Like the picture is the only tether. But you… you ran with the boy first. You did what she would have wanted.”

Lillian’s eyes filled. She looked at Eliza’s face behind the glass and imagined her daughter’s voice, bossy and bright, insisting that of course they should save the baby, of course they should save each other. Lillian realized then that grief had been teaching her something slowly, painfully, and that perhaps she had finally learned a piece of it: memory was not meant to trap the living. It was meant to guide them.

That same week, Gideon Hale returned to Virginia City, older now, his hair threaded with gray. He arrived not because he sensed their fire or their near-loss, but because he had work in town and because some part of him, stubborn as a scar, kept returning to places where he had fixed grief onto paper. When he stepped into the Rowan house, he paused again at the threshold the way he had years earlier, as if the air inside might still carry the weight of that first photograph.

Lillian met him in the parlor. She recognized him immediately, though time had changed his face. Gideon looked at the mantel and saw Eliza’s photograph still standing, soot smudged, steady.

“You kept her,” he said quietly.

“We did,” Lillian replied. Then, surprising herself, she added, “And we kept living.”

Gideon’s eyes flickered, and for a moment he looked like a man who had been waiting years to hear that sentence. He sat with them at the table, and for the first time, the Rowans asked him questions they had been too raw to ask before. How many photographs had he made? How did he bear the rooms full of death? Why had he chosen this work?

Gideon held his cup of coffee with both hands, staring into it as if it contained answers. “Because I forgot my sister’s face,” he said finally. “Not all at once. Just… slowly. I had her laugh. I had her hair. But the exact shape of her eyes started to slip. My mother begged my father for a portrait when she was alive and he said we couldn’t afford it, and then after she died, we couldn’t afford it either. When I learned the trade, I told myself I’d never let another family lose the proof of a face if I could help it.”

Lillian listened, feeling the strange comfort of shared reason. Gideon’s work had not been a ghoulish fascination. It had been a form of service, a stubborn refusal to let death have the final edit.

“I thought people would judge us forever,” Lillian admitted, glancing at the photograph. “Sometimes they still do.”

Gideon nodded. “People fear what reminds them they can lose,” he said. “They call it morbid so they don’t have to call it human.”

Thomas, who had been quiet, cleared his throat. “There was a fire,” he said, voice low. “Lillian carried the boy out first.”

Gideon looked at Lillian with something like respect. “That’s the hardest part,” he said. “Not taking the photograph. Not hanging it. The hardest part is letting love move forward without believing it betrays what’s behind.”

Lillian felt her eyes sting, and she did not hide it. She had spent years treating tears as private, as if grief was something that could be managed like finances, balanced and controlled. Now, with Mateo asleep upstairs and Eliza’s photograph steady on the mantel, Lillian allowed herself to cry in front of strangers and found that it did not break her.

In the years that followed, the Rowan house became a place where grief was not a taboo but a language. Lillian helped other mothers contact photographers when illness stole children too quickly. Thomas, when he had extra coins, slipped them into the hands of widows with no questions asked. Mateo grew up knowing that love could stretch, that it could hold both the living and the dead without tearing if the hands were willing.

When Mateo turned eighteen, he stood in the parlor with a small bag packed, ready to leave Virginia City for work farther west. The world was changing, railroads cutting through distances, towns rising and falling like waves. Lillian’s heart clenched at the idea of another departure, yet she refused to trap him.

Mateo glanced at the mantel before he stepped out. “I’m going to take her with me,” he said, and his voice held both certainty and tenderness.

Lillian’s breath caught. “The photograph?” she asked, startled.

Mateo nodded. “Not forever,” he said quickly, as if she might think he was stealing. “Just… for now. I want her to see what I see. I want her to be part of it. You told me she liked adventures.”

Thomas laughed softly, a sound thick with emotion. He lifted the frame and wrapped it in cloth the way he had years ago, careful as a man handling something sacred. He handed it to Mateo, who took it with reverence.

“Bring her back,” Lillian said, her voice trembling, and then she added, because she meant it, “Bring yourself back too, when you can.”

Mateo promised, and then he was gone, the door closing gently behind him. Lillian stood in the parlor staring at the empty spot on the mantel where the photograph had been. The space looked wrong at first, like an unfinished sentence, yet the longer she stared, the more she realized the emptiness was not loss. It was movement. The photograph had left the house not because love had weakened, but because love had expanded its territory.

Years later, when Lillian was old and her hands had begun to tremble, Mateo returned with the photograph and a new frame, sturdier, made by a craftsman in San Francisco. Along with it, he brought a letter he had written during a long train ride, words scratched carefully on paper, words meant to be read aloud.

He sat with Lillian and Thomas in the parlor, the same parlor where Eliza had once been placed upright in a chair, and he read. In the letter, he spoke of cities and oceans and the strangeness of seeing the world continue beyond the boundaries of a mining town. He spoke of loneliness and the comfort of unpacking Eliza’s photograph in boarding houses, of setting it on a small table and feeling less untethered. He spoke of meeting other people who carried photographs of dead children, and of how, once he had seen enough of them, he stopped thinking of the images as grim and began to think of them as a kind of choir: countless faces insisting, silently, that they had mattered.

At the end of the letter, Mateo wrote, “I used to think the picture was for you, because you were the ones who lost her. Now I think it’s for anyone who needs to learn that love does not stop because a heartbeat does. Love changes shape. Sometimes it becomes a story. Sometimes it becomes a stranger’s kindness. Sometimes it becomes a photograph that someone stands in front of, meeting a child’s eyes across time, and realizing that grief is not shameful. It is proof of attachment.”

Lillian listened, tears slipping down her cheeks, and she did not wipe them away. Thomas reached for her hand. Their fingers intertwined, old hands with scars and wrinkles, hands that had held a child, held a photograph, held a boy who had become a man.

When Thomas died, and later when Lillian followed him, Mateo kept the photograph, as he had promised, but he did not hide it. He donated it, with the Rowans’ permission written in ink that shook, to the small historical society that had begun collecting artifacts of Virginia City’s earlier years. Along with the photograph, he left a note, not about morbidity, not about spectacle, but about memory as an act of courage.

Visitors came and stood before the framed image of Eliza Rowan, eight years old forever, curls pinned as if morning might still wake her. Some flinched, because they carried their own fears. Some stared too long, because curiosity and grief sometimes wore the same face. Yet many, more than Mateo expected, simply stood in silence with softened eyes, recognizing something older than judgment.

They recognized the truth that the Rowans had learned the hard way and carried with them like a promise wrapped in cloth: in a world where children vanished to sickness and silence, remembrance was not a strange indulgence. It was resistance. It was love refusing to be erased. And if the last place a parent could meet a child’s eyes was a small rectangle of paper held steady against time, then standing there was not morbid at all.

It was human.

News

a Widow Chose Her Tallest Slave for Her Five Daughters… to Create a New Bloodline

Sabine felt, for a brief, unsettling moment, as if she had been seen. Then she corrected the feeling the way…

Thomas Brennan had built his life the way a careful man stacks coins on a table: not too many, never near the edge, always counted twice before he turned out the lamp.

Mrs. Kincaid’s eyes softened, but she did not coo. She nodded once, slow, respectful. “I’m sorry,” she said. “There are…

Mary learned early that hunger has a voice.

Eli barreled in last, nine years old and built from restless energy, the kind that never seemed to run out…

The Unholy Case of the Plantation Triplets the Masters Could Not Control

A small cabin sat a little distance away, newer than the ruins, patched with tin and prayer. On its porch…

Given to a Duke Far Too Old, She Wept for Her Dreams—But on Wedding Night His First Gift Amazed Her

For a long time, he said nothing. Isolde told herself she preferred it. Then, as the carriage turned onto a…

She Married a Poor Mountain Man but he drove her to His Secret Hidden Mansion

Mara stayed by the table, her needle paused mid-stitch, watching him the way you watched a stranger near a cliff…

End of content

No more pages to load