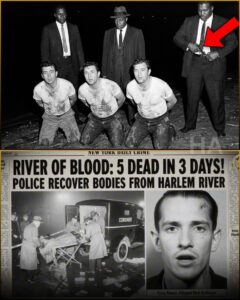

THEY MURDERED 18-YEAR-OLD RUBY WILLIAMS, AND IN THREE DAYS BUMPY JOHNSON MADE THE CITY LOOK AWAY

Prologue: 2:38 A.M., June 4th, 1946, Marcus Williams’ Apartment, Harlem

The clock over the sink clicked like it had a grudge, each tick pressing a thumb into Marcus Williams’ ribs. Harlem outside the window was dark and damp, the kind of darkness that made streetlights look tired, but the apartment kitchen was bright enough to be cruel. Marcus sat at the table in his shirtsleeves, shoulders locked, staring at a revolver that seemed too small to hold all the anger in the room. The .38 had cost forty-seven dollars at a pawn shop in the Bronx, money he did not have, money he scraped together because he could not stand the feeling of being empty-handed in a world that had taken his daughter and still expected him to behave.

Ruby was eighteen. Ruby had laughed too loudly when she got excited about a book, then apologized for it as if joy needed permission. Ruby had wanted to be a teacher, not just anywhere, but here, in Harlem, because she believed children deserved to grow up inside possibility instead of fear. Now she was dead, and the police had made him identify her at the morgue, then leaned close like they were sharing a private joke and asked if she had been “working.” Marcus did not remember what he said back. He only remembered the sound of his wife’s breath, broken into little shards, and the way the fluorescent light had made Ruby’s skin look like paper left too long in the sun.

On the counter, the official report sat folded like an insult you were expected to frame. “Colored female. Approximately eighteen. Evidence suggests prostitution-related incident. No suspects. Low priority.” Low priority. Marcus kept circling those words in his mind because he could not find a different way to translate them. Low priority meant her life weighed less than a stranger’s inconvenience. Low priority meant a man could hurt her and go home and eat dinner like nothing happened. Low priority meant the system had looked at Marcus and Evelyn and decided their grief was not worth the paperwork.

Behind him, from the bedroom, Evelyn cried the way the ocean cries in a storm, not loud at first, then loud enough to change the shape of the air. She had been crying since they brought Ruby home from the morgue, the sound of it settling into the walls as if the apartment itself had learned a new language. Marcus did not move. He watched the revolver and tried to imagine what it would feel like to become the kind of man who pulled a trigger on purpose, the kind of man who did not stop to ask permission from the law.

“Mark,” Evelyn said, and her voice was so thin he almost missed it. He turned and saw her in the bedroom doorway, hair loose, face swollen, hands trembling like the grief was electrical. “Call him.”

Marcus blinked as if she had spoken nonsense. “No.”

“Mark, please.” She stepped forward one careful step, as if her bones had turned fragile. “I’m not asking because I want to. I’m asking because I can’t see another road. Not after what they said about her.”

He tried to harden himself, tried to find the old rules that used to hold him together. “I haven’t spoken to him in ten years. He’s a gangster. I’m not.”

Evelyn’s laugh came out wrong, like something splintering. “Police don’t care,” she said, and fresh tears ran down her cheeks without hesitation, as if her body had decided crying was the only honest thing left. “Courts don’t care. Nobody in this whole goddamn city cares that our Ruby is dead. Nobody cares that they beat her, that they—” The rest collapsed into a sob that made her fold against the doorframe.

Marcus stood so fast the chair scraped the floor. He crossed the kitchen, caught his wife before she slid down, held her while she shook. He could feel her ribs rattling under his palms, her grief trying to escape her body through any crack it could find.

“I won’t let them get away with it,” he whispered, but the words were more prayer than plan. “I’ll find them.”

“You’ll die,” Evelyn whispered into his chest, not dramatic, just certain. “You’ll take that gun and you’ll die. And then I’ll have lost both of you, and Ruby’s killers will still be walking free. Then what am I supposed to do?”

Marcus pulled back, and his voice cracked like old wood. “Tell me, Evelyn. What the hell am I supposed to do?”

She stared at him with eyes that looked older than yesterday. “Call him,” she said again, and this time her voice held steel under the sorrow. “Call Bumpy Johnson. He’s the only person in this city with the power to make this right. The only person who will actually do something. Please, Mark. For Ruby.”

Marcus looked at the revolver, then at his wife, and he understood something that made him feel ashamed and relieved at the same time. He had always known this day might come. Deep down, beneath his trust in uniforms and paperwork and the idea of America, he had kept a number memorized like a hidden exit.

His hands shook as he dialed.

The phone rang once, twice, three times. Then a voice answered, deep and calm, as if it had been awake waiting for the world to catch up.

“Mark.”

Marcus swallowed and tasted salt. “Bump,” he said, and the name sounded like a door he had sworn never to open again. His throat tightened until the next words almost couldn’t fit through. “They killed my Ruby.”

Silence held the line for five seconds, five long seconds that felt like the city pausing to listen. Then Bumpy Johnson’s voice returned, quieter now, colder, like January breath.

“I’m coming.”

The line went dead.

Marcus stood in the kitchen with the receiver in his hand, listening to the dial tone as if it might change its mind and bring Ruby back. Then he set the phone down, walked to the table, and did something that felt like surrender. He opened the revolver, removed the bullets one by one, and slid them into his pocket. He placed the gun back in its box.

Because if Bumpy Johnson was coming, Marcus would not need a weapon. He would need a witness.

Part One: Ruby Williams Was Not a File

Ruby Williams had a way of making ordinary things feel like they belonged to the future. She was the girl who carried library books pressed against her chest like armor, the girl who sang in the choir at Abyssinian Baptist Church every Sunday and smiled at old women as if their wrinkles were maps worth studying. She had graduated near the top of her class at Wadley High School, and when her name was called, she walked across the stage with a confidence that made Marcus squeeze Evelyn’s hand until her rings bit into her finger. Ruby had been accepted to Howard University with a scholarship that covered everything, tuition and room and board, the whole distant world that Marcus and Evelyn had never been able to afford but had always prayed their daughter might reach.

She wanted to be a teacher. Not because she thought teaching was easy, but because she understood what it meant to be seen by an adult who expected you to become something. Ruby talked about classrooms the way some people talked about cathedrals, with reverence and intention. She wanted to come back to Harlem and teach young children to read, to look at their own lives and feel possibility instead of limitation. She said it like she believed it, and Marcus loved her for that, even when it scared him, even when it made him wonder if she was too soft for the world.

Marcus worked for the Post Office, steady as sunrise, and Evelyn cleaned houses downtown for white families who called her “girl” even when she wore her best dress. They were respectable people, the kind of family Harlem held up as proof that survival could become progress. They raised Ruby to believe in rules and work and patience, to believe that if you did everything right, the system would eventually do right by you.

Then June 3rd, 1946 arrived and taught Harlem a lesson it had already learned too many times: doing everything right did not make you untouchable.

That Sunday afternoon, Ruby left church carrying three library books and her Bible, wearing a yellow summer dress Evelyn had sewn with careful stitches and quiet pride. She walked down Lennox Avenue the way she always did, same route, same time, head up, not because she was fearless, but because she had been taught that decent girls didn’t walk like prey.

She never saw the sedan pull alongside her.

Witnesses would later remember the quickness of it, the efficient choreography of men who moved like they had rehearsed. Two jumped out, grabbed her arms, pulled her toward the car as she screamed. Another pressed something against her mouth. Her scream broke into a gasp, then disappeared. In fifteen seconds, Ruby Williams was gone, swallowed by traffic and the city’s practiced habit of looking away.

There were witnesses. A dozen, maybe more. Men who pretended to tie their shoes. Women who suddenly found a reason to cross the street. Teenagers who stared, then looked down like their eyes might get them hurt. In 1946 Harlem, people understood the dangerous math of reporting crimes involving white men and Black girls. Sometimes calling the police did not bring help. Sometimes it brought questions that sounded like blame. Sometimes it brought handcuffs.

So the street kept moving.

Ruby did not come home for dinner.

By evening, Evelyn’s worry turned sharp. By night, it turned desperate. Marcus searched the neighborhood, then the library, then the hospital corridors that smelled like bleach and resignation. Around 9:30 p.m., police knocked on their door and asked them to come identify a body.

The morgue was cold in a way that felt personal. Ruby lay on a metal table, and Marcus tried to make his mind refuse the image, tried to find a loophole in reality. Evelyn made a sound that seemed too old to come from her. And the detective, impatient, asked if Ruby had been involved in prostitution.

That question, that casual ugliness, was the moment Marcus felt the floor shift. It was the moment he realized the system had already decided who Ruby was, and it had decided she was disposable.

By Tuesday morning, the file existed, and the file was already closed.

Part Two: The Hunters Who Thought They Were Safe

Monsters rarely introduce themselves as monsters. In bars, they laugh. On street corners, they slap each other on the back. They wear clean shirts and tip their hats to women they respect, then use different hands on women they do not.

Tony Russo was twenty-six and already certain of his own immunity. He worked the dirty edges of East Harlem for men with better suits and bigger offices, collecting debts, reminding people what fear felt like. Tony liked power most when it was lopsided. He liked it when there was no risk.

Eight months earlier, in October 1945, a sixteen-year-old girl named Dorothy Jenkins had disappeared walking home from her job at a laundry. Three days later, her body was found in an abandoned building. The investigation lasted what felt like a blink. A few notes, a few shrugged shoulders, and then a label that turned tragedy into routine: troubled girl, street work, file closed.

Dorothy’s family did not have money for lawyers or influence. Their grief stayed inside their apartment because grief outside could attract the wrong kind of attention. Tony’s crew celebrated in a bar on 116th Street because the lack of consequences felt like permission. They told themselves the lie they wanted to be true, the lie the city often supported: no one cares. Not enough to do anything.

By May 1946, boredom returned and greed followed. They watched Ruby for weeks, noticing her routine, her books, the way she walked as if she belonged to her own future. To them, she was not a person. She was a test of the world’s indifference. They wanted to prove, again, that they could do the worst thing and still be safe.

When they took her, they took more than a life. They took a promise Harlem had made to itself, that education could be a shield. They took the idea that decency was protection.

And when the police closed the case, Tony and his men celebrated the way gamblers celebrate a lucky hand, convinced the game itself had been rigged in their favor.

They did not know someone in Harlem had just dialed a number that changed the rules.

Part Three: The Return of Bumpy Johnson

When Bumpy Johnson arrived at Marcus Williams’ apartment at 3:17 a.m., he came alone. No entourage, no men posted like punctuation behind him. He wore a black suit that fit like it had been tailored for funerals. His face was calm in a way that made Marcus uneasy, because Marcus had known him as a boy, had seen him angry, had seen him laugh, had seen him fight. Calm, on Bumpy, did not mean peace. Calm meant decision.

Marcus opened the door immediately, as if his body had been waiting at attention.

For a moment they stood there and looked at each other, two childhood friends who had grown into different definitions of manhood. Marcus had spent his life believing in rules, in showing up on time, in building respectability one paycheck at a time. Bumpy had spent his life learning the other architecture of the city, the hidden stairwells of influence, the corners where money and fear traded hands.

“Mark,” Bumpy said quietly.

Marcus’ throat tightened, and for a second he wanted to be eight years old again, running through summer streets, believing the world was big enough for innocence.

They embraced, brief and awkward, then Bumpy stepped inside.

Evelyn sat on the couch with her hands folded so tightly her knuckles looked pale. When she saw Bumpy, she stood as if rising for a judge.

“Thank you for coming,” she whispered.

Bumpy nodded once, then looked at Marcus. “Tell me.”

So they told him. Every detail they could bear. Ruby leaving church. Ruby not coming home. The police. The morgue. The question that turned their daughter into an accusation. Evelyn’s voice broke when she described Ruby’s injuries, and Marcus felt his own rage flare hot enough to make him dizzy, but Bumpy listened without interruption.

Marcus watched Bumpy’s eyes because the rest of his face gave nothing away. In those eyes, Marcus saw something like winter steel, cold and controlled, a fury that had learned to wear manners.

When they finished, Bumpy was silent for a long moment. Then he asked a question that sounded simple but carried weight.

“Do the police know who did it?”

“They’re not even looking,” Marcus said, bitterness rising like bile. “They called her a prostitute and closed the case. Said they have real cases to work.”

Bumpy moved to the window and looked out at Harlem’s sleeping streets. “I need to know something, Mark. I need to know if you’re prepared for what happens next.”

Marcus did not hesitate. “Yes.”

Bumpy turned slightly, enough that Marcus could see the outline of him in the kitchen light. “Because what I’m going to do isn’t legal,” he said, not bragging, not warning, just stating weather. “It won’t bring Ruby back. And when it’s done, it’s done.”

“I don’t care about legal,” Marcus answered, and surprised himself with how steady his voice sounded. “The law didn’t protect Ruby. So yes, Bump. I want them to pay.”

Evelyn stepped closer, her grief now shaped into something sharper. “Please,” she said. “Make them understand what they took.”

Bumpy’s eyes softened, not into mercy, but into recognition. “I promise you,” he said. “They’ll understand.”

At the door, he paused. “Ruby’s funeral?”

“Saturday, June 15th,” Marcus said. “Woodlawn Cemetery.”

“I’ll be there,” Bumpy replied, and then he left, his footsteps disappearing into the night.

Marcus stood in the doorway watching him go, and an old, uncomfortable truth settled into Marcus’ bones. The city had laws, but it also had power, and power did not always wear a badge.

Part Four: Business, Territory, and the Price of Heat

By Tuesday morning, Bumpy was in his office above a jazz club, the kind of place where music rose through the floorboards and smoke curled like secrets. Theodore “Teddy” Green, his attorney and adviser, sat across from him, listening as Bumpy spoke in the calm tone men use when they have already made peace with what they are about to do.

“This happened in East Harlem,” Bumpy said. “Italian territory.”

Teddy’s eyes narrowed. “You think they’re connected.”

“They operate there. And I don’t believe this was the first time.”

Teddy exhaled slowly, as if measuring the risk in the air. “You want to talk to Costello.”

Bumpy nodded once. “If this crew belongs to him, I need to know whether he’s going to protect them or step aside.”

“And if he protects them,” Teddy asked, already knowing the answer.

“Then it starts a war,” Bumpy said.

The meeting happened in Little Italy in a back room where respect and threat lived side by side like twin brothers. Frank Costello looked like a banker, which was part of the point. Power did not always need to shout. Sometimes it just needed to be believed.

Bumpy explained what happened to Ruby without decoration. He watched Costello’s face, but Costello’s expression barely moved, as if he were hearing the weather report.

When Bumpy finished, Costello made a phone call, asked questions, listened, then hung up and stared at Bumpy with a new kind of focus.

“Tony Russo,” Costello said finally. “And four men with him. Bottom-level. Not made. Enforcers, collectors.”

Bumpy’s jaw tightened. “Are they under your protection?”

Costello walked to the window and looked out at the street like the answer was written there. “They’re a liability,” he said. “Not just stupid. Dangerous to business. Heat brings trouble. Trouble brings investigations. Investigations bring men who don’t understand arrangements.”

He turned back. “I can’t be seen ordering anything against my own people, even low-level. Bad message. But I’ll tell you this. Tony Russo and his crew are not under my protection. If something happens to them, I don’t ask questions. I don’t retaliate.”

Bumpy held his gaze, two men speaking the language of consequence as if it were ordinary.

Costello’s voice dropped another degree. “Kids are off limits,” he said. “Always have been. These five crossed a line that shouldn’t exist.”

Bumpy stood, the meeting ending the way storms end, not with closure, but with motion. “Keep it contained,” he said. “No newspapers connecting anything to murdered girls. Make it look like street violence.”

Costello nodded. “Bodies show up, police call it gang business, and the city moves on,” he said, and the coldness of his certainty felt like its own indictment.

Bumpy walked out with five names, five addresses, and the kind of permission that did not come from courts.

Back in Harlem, he laid photographs on a table in front of four trusted men. Willie Lee. Marcus Cole. James “Quick” Jackson. Teddy Green, who remained because someone had to keep track of the legal edges, even when everyone stepped over them.

“These are the men,” Bumpy said, tapping each photo with a finger like a judge tapping a gavel. “We do this fast. We do it quiet. And we make sure everyone understands why.”

He wrote a note on waterproof paper in block letters, deliberate as scripture: Ruby Williams. 18 years old. She wanted to be a teacher. You murdered her. This is justice. Harlem remembers.

“We leave this with each one,” Bumpy said. “And the police will back off, because investigating means admitting they failed her.”

Teddy’s mouth tightened. “You’re betting on their shame.”

Bumpy’s eyes did not blink. “I’m betting on their convenience,” he said. “Shame is too expensive for some men.”

Part Five: Three Days and a River That Carried a Message

The first night was thick with humidity and laughter spilling out of bars. Tony Russo left Carlos’ on 116th Street drunk and loose, enjoying the easy confidence of a man who thought the city was built to forgive him. He did not notice the car trailing him. He did not notice how the street seemed to empty just slightly, as if the night itself had decided not to witness what came next.

He turned a corner, humming, and then he was on the ground, pain shouting louder than his pride. A man stepped from a doorway, face unreadable, eyes flat. Another car rolled up. Hands hauled Tony into the back seat with the efficiency of men who had done difficult things before and knew the value of speed.

Where they took him was not a mystery to Bumpy. Places held memories, and some places deserved to be haunted.

Hours later, Bumpy walked into an empty warehouse carrying a briefcase and Ruby’s graduation photo. Tony’s bravado had leaked out of him, leaving only fear and disbelief. He saw the photo and recognized it the way guilty men recognize truth, instantly.

“She had a name,” Bumpy said, voice quiet. “She had plans. You thought you could erase all of that because the city wouldn’t bother to remember.”

Tony begged. Promised. Offered confessions to a system that had already demonstrated it did not care. Bumpy listened without emotion, because this was not negotiation. This was consequence.

What happened after was not the kind of story decent people repeat in detail. Harlem did not need the gore. Harlem needed the meaning. Tony talked, because pain has a way of loosening secrets. He gave addresses, routines, names, confirmations of what they had done and how often they had done it. When dawn began to pale the edges of the city, Tony Russo was gone from the world.

Before sunrise, the river received its first message.

The next night, two more were taken from a card game. The work was quick, professional, grim. They woke in a soundproof basement facing each other across empty space, the kind of space that becomes an ocean when fear fills it. Bumpy sat between them like a clock.

“You grabbed her,” he said, not asking. “Broad daylight. Like you were taking a purse.”

They denied at first, then pleaded. They offered jail as if jail would have been their sentence, as if the courts would have looked at them and Ruby and found justice instead of excuses. Bumpy held Ruby’s photograph up to their faces, and something in them cracked, not into goodness, but into panic.

“You believed there would be no consequences,” Bumpy said. “Tonight you learn you were wrong.”

The rest happened out of sight, behind closed doors, where the men who did it would carry the memory like a stain. Harlem did not cheer the suffering. Harlem absorbed the fact of it, the way a neighborhood absorbs thunder and still goes to work in the morning.

By Friday morning, the river carried more.

By Friday afternoon, Vinnie Carbone was taken outside his apartment, struck down in a quick blur. When he woke, Bumpy was there again, calm as a judge, holding the story steady so Vinnie could not wriggle out of it.

“You covered her mouth,” Bumpy said. “You made her disappear.”

Vinnie cried. He said he was sorry the way people say sorry when the word is trying to buy time. Bumpy did not bargain with apologies.

By evening, the river received another body and another note.

The last man, Frank Russo, was found in a church in the Bronx late Saturday night, kneeling at an altar like he believed prayer could rewrite history. Bumpy walked down the aisle slowly, shoes clicking against worn wood.

“God’s not listening,” Bumpy said, not cruelly, but plainly.

Frank turned, eyes wet, and pleaded, insisting he had been dragged into it, insisting he had watched but not wanted, as if reluctance were innocence. Bumpy looked at him for a long moment, then raised his gun.

“You get mercy the others didn’t,” he said softly, because something about the church made even hard men remember they had souls. The shot was quick. The echo rolled through the empty sanctuary like a slammed door.

By 1:00 a.m. Sunday morning, the river carried its fifth message.

Part Six: The Detective Who Knew and the Captain Who Didn’t Want to Know

Sunday, June 9th, 6:47 a.m., Detective Robert Walsh stood by the Harlem River and stared at the water as if it might confess. The shoreline looked darker in spots, stained by what the current had carried before it smoothed the evidence away. Uniformed officers hauled a body up onto the embankment, white male, twenties, face bruised by the river’s rough handling, and pinned to his chest was the note, the same note they had found on the others.

Walsh read it anyway, because reading it felt like penance.

Ruby Williams. 18 years old. She wanted to be a teacher. You murdered her. This is justice. Harlem remembers.

Captain Riley walked up beside him, eyes tired, mouth tight.

“Five bodies in three days,” Riley muttered.

“Five men who murdered Ruby Williams,” Walsh replied.

Riley hesitated, because the name itself threatened to reopen a file that had been closed with shameful speed. “You sure?”

Walsh laughed once, bitter and brief. “I pulled the old reports,” he said. “Same territory, same rumors. The system didn’t care until the river started delivering messages.”

Riley looked away, toward the water. “Can we prove anything?”

Walsh stared at him. “Prove what?” he asked, voice low. “That Bumpy Johnson killed men we were never going to convict anyway? You want that trial, Captain? You want Bumpy in court telling a jury exactly why he did it, while reporters write about how we called an eighteen-year-old honor student a prostitute and closed her case in hours?”

Riley’s jaw clenched. He wasn’t a good man or a bad one in that moment, just a man balancing a badge against a city’s hypocrisy.

“What’s our statement?” he asked finally.

Walsh already knew. “Gang violence,” he said. “Internal dispute. No suspects. Investigation ongoing.”

“And Ruby?” Riley asked, almost whispering.

Walsh held his gaze. “Ruby stays closed,” he said, and the words felt like swallowing glass.

Riley nodded once, and that nod was the sound of the city deciding to look away.

Part Seven: A Funeral and a Different Kind of Promise

Saturday, June 15th, 1946, more than three thousand people crowded into Abyssinian Baptist Church. Most had never met Ruby Williams, but they came because her story had become larger than a family’s grief. It had become a mirror held up to the city, forcing Harlem to see what the system did when it decided you were low priority.

Ruby’s casket sat at the front, flowers piled high like an attempt to soften the unbearable. Marcus sat beside Evelyn, holding her hand as if it were the only thing keeping him anchored to earth. Their son James, twelve years old, sat rigidly, eyes too old, jaw clenched like a man already learning what rage costs.

Reverend Adam Clayton Powell Jr. stood at the pulpit, handsome and sharp-eyed, voice built for both comfort and confrontation. He spoke of Ruby as a child of promise, a young woman who represented Harlem at its best, intelligent and kind and determined. He spoke of the police report without naming it, and the congregation understood, a collective intake of breath at a truth everyone knew.

He did not say Bumpy’s name either, but Harlem heard it anyway, humming under the words like bass under a hymn.

“I will not tell you whether what happened last week was right or wrong,” Powell said, voice steady. “That is between those involved and God. But I will tell you this. Ruby Williams did not die forgotten. She did not die without consequence. And perhaps that is the only comfort this city has allowed her family.”

After the service, as the pallbearers lifted the casket, Marcus saw Bumpy standing at the back of the church, black suit, face calm, eyes heavy. Marcus walked to him, legs unsteady, and for a moment neither spoke. Words felt too small.

“Thank you,” Marcus said at last, and his voice broke anyway.

Bumpy nodded. “I kept my promise.”

Evelyn stepped close, eyes still swollen but clearer now, as if grief had hardened into purpose. “Did they understand?” she asked.

Bumpy’s gaze flicked toward the casket. “Every one of them knew her name,” he said quietly. “They knew what they did. They knew why.”

Evelyn closed her eyes, and a tear slid down her cheek like a final sentence. “Good,” she whispered, not because it brought Ruby back, but because it told the world Ruby’s life had weight.

At Woodlawn Cemetery, under a June sun that seemed indecently bright, Ruby was lowered into the earth while thousands watched. When the casket settled, Bumpy stepped forward. He placed something atop the flowers, not dramatic, not performative, just deliberate.

Five photographs.

Marcus saw the faces and felt his stomach twist, not with satisfaction, but with a complicated ache. Beneath them, Bumpy left a note in his own handwriting, smaller than the river notes, meant only for Ruby and the people who loved her.

Ruby, they paid. Every single one of them. Rest well, sister. Harlem protects its own.

Bumpy stepped back into the crowd and vanished the way shadows vanish, not gone, just absorbed by the city.

Epilogue: What Justice Leaves Behind

In the weeks that followed, newspapers called the river deaths gang violence and moved on, because newspapers were trained to treat Harlem’s pain like weather. The police continued to pretend Ruby Williams had been low priority, because admitting otherwise would require them to admit how easily they had dismissed her.

But Harlem did not move on the same way.

In barber shops, men spoke Ruby’s name like a warning and a prayer. In kitchens, women told their daughters to walk in pairs and keep their heads high anyway, because fear could not be allowed to become the only inheritance. In church basements, organizers started talking more openly, not just about grief, but about power, about the way systems respond only when forced.

Marcus returned to the Post Office because the world did not pause for tragedy, but he was no longer the same man who had believed obedience guaranteed protection. He began attending meetings, listening to voices that spoke of rights and accountability, of refusing to let files close quietly. Evelyn, exhausted and grieving, began sewing again, not dresses this time, but banners for community gatherings, words stitched into cloth like stubborn light.

James, Ruby’s little brother, grew up inside the crater her death left behind. For a long time he carried rage like a second spine. But he also carried Ruby’s books, the ones she had loved, and he read them the way a boy reads a map out of a burning building. Years later, when he stood in front of a classroom in Harlem, chalk dust on his hands, he heard Ruby’s voice in the back of his mind, laughing too loudly, then apologizing for it. He did not apologize for his hope.

A scholarship fund was created in Ruby’s name, small at first, built from church donations and quiet contributions from people who did not advertise their generosity. One envelope arrived with no return address, thick with bills, enough to send two students to college for a year. Marcus stared at the money, knowing without proof whose hand had placed it into motion. Evelyn folded the envelope, set it in the kitchen drawer beside Ruby’s last church program, and said nothing. Some truths did not need to be spoken aloud to be understood.

And Bumpy Johnson, the man who had moved like a shadow through those three days, carried his own consequence too. In Harlem, some called him a protector. Others called him a sinner with good aim. Bumpy did not correct either side. He continued to walk the line he had always walked, balancing community loyalty against criminal reality, knowing the city would never grant him the title of hero, and perhaps knowing he did not deserve it.

What remained, what Harlem held onto, was not the river or the bodies or the silence of the NYPD. What remained was Ruby’s name, spoken until it became a refusal to forget. Ruby Williams, eighteen years old, a future teacher, an honor student, a daughter who had been treated like low priority by a system built to weigh lives unequally.

Harlem remembered anyway.

And somewhere in the city, long after the headlines faded, the lesson stayed carved into the air like a scar: when the law fails, people find other ways to demand that a life mattered, and sometimes the most human ending you can offer the dead is this, that their story does not vanish, and their name becomes a lantern in a neighborhood that refuses to go dark.

News

All Doctors Gave Up… Billionaire Declared DEAD—Until Poor Maid’s Toddler Slept On Him Overnight

The private wing of St. Gabriel Medical Center had its own kind of silence, the expensive kind, padded and perfumed…

Mafia Boss Arrived Home Unannounced And Saw The Maid With His Triplets — What He Saw Froze Him

Vincent Moretti didn’t announce his return because men like him never did. In his world, surprises kept you breathing. Schedules…

Poor Waitress Shielded An Old Man From Gunmen – Next Day, Mafia Boss Sends 4 Guards To Her Cafe

The gun hovered so close to her chest that she could see the tiny scratch on the barrel, the place…

Her Therapist Calls The Mafia Boss — She Didn’t Trip Someone Smashed Her Ankle

Clara Wynn pressed her palm to the corridor’s paneled wall, not because she needed the support, but because she needed…

Unaware Her Father Was A Secret Trillionaire Who Bought His Company, Husband Signs Divorce Papers On

The divorce papers landed on the blanket like an insult dressed in linen. Not tossed, not dropped, not even hurried,…

She Got in the Wrong Car on Christmas Eve, Mafia Boss Locked the Doors and said ‘You’re Not Leaving”

Emma Hart got into the wrong car at 11:47 p.m. on Christmas Eve with a dead phone, a discount dress,…

End of content

No more pages to load