Hawthorne Ridge, Georgia, March of 1847, sweated under an early heat that made even the church bell sound tired. The town had been born from the last echoes of a gold rush in the foothills and kept alive by cotton, corn, and the stubborn pride of men who measured themselves in acreage and gossip. In Hawthorne Ridge, reputations weren’t earned so much as stitched together in the square, thread by thread, with every handshake and every whisper. A person could be crowned in the morning and ruined by supper, and the whole process happened in plain daylight, as if shame was just another commodity laid out on a table.

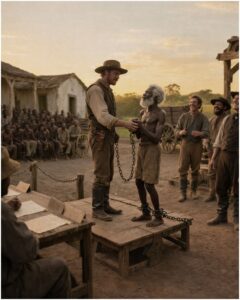

That morning, the table was literal.

The monthly auction had drawn a crowd that treated misery like entertainment and bargaining like sport. Planters came in polished boots. Merchants came with ledgers and soft smiles. A few miners from the hills wandered in, pockets lighter than their bravado, eager to watch someone else gamble. Horses stamped. Flies orbited. The auctioneer, Abner Price, climbed his platform and lifted his gavel as if he were about to conduct an orchestra rather than sell human beings.

Among the lot of men and women lined up below, there was one who pulled the eye for all the wrong reasons.

He was old, unmistakably so, with white hair that looked like it had surrendered long ago and a face carved by years that hadn’t bothered to be gentle. His shoulders curved forward, not from humility, but from a body that had been forced to carry too much for too long. His clothing was ragged, his wrists marked with old scars, and his hands trembled, though his chin stayed lifted in a quiet refusal to bow for anyone’s amusement.

Abner Price’s voice dipped into impatience as he reached the final names. “Next,” he said, waving as if shooing a stray dog from a porch, “we have… Mark. Some call him Old Mark. Brought from Angola decades back. Sixty-five, seventy, who knows. Not fit for heavy work. Might do small tasks if you’ve got the charity for it. We’ll start at one hundred and fifty dollars.”

The number was low enough to spark laughter, the kind that came easy when it wasn’t your life being measured. Strong young men often sold for a thousand dollars or more, sometimes much more. One hundred and fifty was what a man might pay for a decent horse, and even then he would examine the animal’s teeth first.

“Who’s buying a walking funeral?” someone called.

“Price ought to throw him in free with a sack of feed,” another said.

Abner tapped his gavel. “One-fifty,” he repeated, trying to sound hopeful. “Do I hear one-fifty?”

Silence answered him. People shifted. Conversations restarted. A few men began turning away, already thinking about lunch. Abner dropped the price as if lowering a bucket into a dry well. “One-twenty-five. One hundred. Seventy-five.”

Still nothing.

Old Mark stood there in the sun as if he were a fence post that nobody wanted, eyes fixed on a point beyond the crowd. It would have been easy to mistake that stillness for emptiness. Only someone who knew how to look would notice the way he watched hands instead of faces, the way his gaze sharpened when the auctioneer’s voice changed, the way his attention moved like a needle searching for something true.

Then a clear voice cut through the mumble of the square.

“Six hundred.”

The air snapped.

Heads turned as one, like birds startled from a field. Six hundred dollars was four times the last called price, and in Hawthorne Ridge it was also a declaration. It said: I am either foolish, or I know something you don’t.

The bidder stepped forward from the shade near the mercantile awning. Samuel Hart was thirty-eight, a widower with a farm outside town that produced enough to keep him fed and respectable but not enough to make him untouchable. He wasn’t the sort who laughed loud in public or bragged over cards. People called him steady, sometimes as praise and sometimes as boredom. Since his wife died of fever three years earlier, he had moved through town like a man carrying a stone in his chest, speaking when needed, disappearing when not.

Abner Price blinked, gavel frozen. “Mr. Hart,” he stammered. “Did you say six hundred?”

Samuel didn’t flinch. “Six hundred.”

Abner’s eyes swept the crowd, hungry for a counterbid that would rescue the auction from confusion and maybe, if he was lucky, from becoming a joke at his expense. “Do I hear… six-fifty? Seven?”

No one answered. They were too busy staring at Samuel as if he’d announced he intended to plant salt instead of seed.

“Six hundred once,” Abner said, uncertain.

From the front row, Colonel Everett Baines, one of the richest planters in the county, leaned forward with a grin that had never met consequences. “Hart,” he called, loud enough for the whole square to enjoy it, “you gone soft in the head? Paying six hundred for a man who can barely stand. He’ll be dead before summer. Might as well throw your money into the river.”

A merchant chimed in, voice slick with mock sympathy. “If you were lonely, Sam, you could’ve bought a dog. At least it’ll fetch.”

Laughter rolled through the crowd, warm and satisfied, like butter melting. Samuel listened without offering them even the courtesy of a reaction. If anything, his calm made them laugh harder, because nothing irritated Hawthorne Ridge like a man who refused to perform.

Abner brought the gavel down. “Sold to Mr. Samuel Hart for six hundred dollars.”

As coins and notes exchanged hands, Old Mark lifted his eyes to Samuel. Close up, the old man’s gaze held something the crowd had missed: not pleading, not dullness, but a sharp intelligence banked under exhaustion, like coals buried in ash. Samuel walked to him and lowered his voice, careful not to turn the moment into a show.

“Can you make it to my wagon,” Samuel asked, “or do you need help?”

Old Mark’s voice, when it came, surprised Samuel. It wasn’t frail. It was steady, accented, and clear, as if he had stored strength in his throat even when his limbs had none to spare. “I can walk, sir. Thank you for asking.”

That simple sentence did something to Samuel, not like a thunderclap, but like a lock turning. Most men in town never asked. They ordered, they barked, they assumed. Asking meant you acknowledged the old man had an answer worth hearing.

As they left the square, the laughter followed them like thrown pebbles.

“Six hundred wasted!”

“Old Mark will croak by Easter!”

Samuel climbed into his wagon without looking back. He drove out of town under a sky the color of hot tin, and for a long stretch the only sound was the wagon wheels and the soft rasp of Old Mark’s breathing.

Old Mark didn’t speak first. He had learned, long ago, that questions could be punished. He sat upright, hands folded, eyes on the road as if he were studying it the way a man studies a wound: with focus, not fear.

Samuel broke the silence gently, as if he were testing the thickness of ice. “You’re wondering why I paid what I did.”

Old Mark turned his head slightly. “A man wonders many things in my position, sir. But yes. I am curious.”

Samuel gave a short, humorless laugh. “They saw an old body and a price tag. I saw a man who survived what should’ve destroyed him and still has something awake behind his eyes.” He paused, feeling the old ache rise, the one that lived in his ribs. “My wife, Anna, used to tell me that the worst sin isn’t cruelty. It’s blindness. Cruel men at least see you enough to hate you. Blind men don’t see you at all.”

Old Mark watched him with a careful expression. “Your wife was wise.”

“She died because our town’s doctor bled her like a hog and called it medicine,” Samuel said, the words coming out harsher than he intended. He tightened his grip on the reins, then forced his voice calmer. “So yes. I’m willing to believe there are kinds of knowledge this town refuses to respect.”

Old Mark’s fingers shifted, the smallest tremor of hesitation. “If you are speaking of knowledge, sir… I had a place once. Before ships. Before chains.”

Samuel glanced at him. “What place?”

Old Mark inhaled slowly. “In my home, people called me Kambale Makori. Here, they call me Mark because it is easy for their tongues. In Angola, I was a healer. A keeper of plant knowledge. My grandfather taught me. His grandfather taught him. There are leaves that draw poison from blood. Bark that quiets fever. Roots that soften pain.”

Samuel’s heart thudded, not with greed, but with recognition. “And you still remember?”

Old Mark’s mouth twitched, not quite a smile, not quite sorrow. “A man forgets many things in suffering, sir. But the body remembers what it needs. The plants… they stayed with me.”

Samuel drove the rest of the way with a strange steadiness, as if the wagon had found a smoother path. The idea of it was almost unbearable: that something useful, something life-saving, had been standing in the square while men laughed, simply because it arrived wrapped in an old, enslaved body.

When they reached Samuel’s farm, the other workers watched from a distance. There were five enslaved people on the property, plus two hired hands. They expected Old Mark to be shoved into the quarters like any other purchase. Instead, Samuel led him behind the main house to a small room, plain but clean, with a bed that had an actual mattress, a wash basin, and a window.

The whispers started immediately, sliding through the yard like wind through tall grass.

That evening Samuel gathered everyone, standing in the yard with the lantern light trembling across faces. “This man,” he said, “will not be doing field work. His joints won’t allow it. He has knowledge that can keep us alive. From now on, if anyone is sick or injured, you tell him first.”

One of the hired hands, Henry Cobb, a broad-shouldered man with skepticism etched into his brow, couldn’t keep quiet. “With respect, Mr. Hart,” Henry said, “you’re telling us to trust our health to an old slave?”

Samuel’s eyes held steady. “I’m telling you to trust results. If his treatments fail, we reconsider. But I’ve buried someone because a man with a diploma couldn’t help her. I’m not burying anyone else just to protect pride.”

Old Mark stood slightly behind Samuel, hands folded, listening without interruption. When Henry scoffed and turned away, Old Mark’s gaze followed him, not with anger, but with the patient look of someone who had watched doubt collapse before.

Samuel gave Old Mark freedom to walk the land. In the mornings the old man moved slowly through the trees and along the creek, pausing to touch leaves, to smell crushed stems, to watch which plants grew near water and which preferred sun. Samuel provided jars, cloth for straining, a mortar and pestle, and a few books that showed drawings of common herbs. Old Mark studied those books with interest, then closed them with the faintest hint of amusement, as if to say, These are the same truths written in a different handwriting.

Two weeks later, the farm’s first test arrived with the smell of burned flesh and the sharp, panicked cry of a young woman named Lila.

She had been cooking in the summer kitchen when her sleeve caught a flame. She slapped at it too late. The burn ran angry red up her forearm, blistering before anyone could fetch water. Henry insisted, loud and frantic, that Samuel send for Dr. Percival Whitcomb in town, the same doctor who treated everyone with leeches and arrogance.

Samuel’s stomach tightened, memory clawing at him, but he didn’t speak from that fear. He called for Old Mark.

Old Mark arrived with calm that seemed almost impossible in a world that punished calm. He examined Lila’s arm, his fingers hovering rather than pressing, eyes narrowing as he measured the depth. “Pain is loud,” he said softly to her, “but it is not always truthful. We will quiet it, then we will heal.”

He disappeared into his room and returned with a salve that smelled of honey and crushed green. “Plantain leaf,” he explained, “and aloe, and pine resin warmed with beeswax. Keeps the wound clean. Pulls heat out. Helps skin remember how to close.”

Lila looked at him with fear and hope braided together. “Will it hurt?”

“It will cool,” Old Mark promised. “And you will breathe again.”

When he spread the salve across the burn, Lila’s shoulders dropped as if someone had loosened a rope around her chest. Within minutes the frantic edge in her eyes softened. “It… it’s not screaming anymore,” she whispered, stunned.

Henry watched, mouth half open, as if he’d expected Old Mark to chant spells and summon smoke. Instead the old man worked like a craftsman, steady and precise, as if healing was simply another form of building.

Over the next days, Old Mark cleaned the wound, re-applied salve, and had Lila drink mild teas to ease swelling and sleep. Ten days later, the burn looked like something that belonged to the past, not something that would brand her for life. The scar that remained was faint, a pale map rather than a jagged ruin.

News traveled faster than wagons. It traveled on tongues and through fences, carried by enslaved people who visited family on neighboring farms and by hired hands who stopped at the tavern for a drink. Soon people were saying Samuel Hart had an African healer on his property who could cool fire and soothe fever.

The second test came for Henry himself, which felt like the world insisting on irony.

He cut his foot on a rusted tool, shrugged it off, then woke days later with his ankle swollen and red streaks crawling up his leg like warning flags. He had seen infections take men down. He had seen a minor cut become a death sentence when the rot moved into the blood.

Henry sat on Samuel’s porch, pale with fear. “Please,” he said hoarsely, pride cracking, “take me to town. Dr. Whitcomb, I’ll pay whatever.”

Samuel crouched in front of him. “Let Old Mark look first,” he said. “If he can’t help, I’ll hitch the wagon myself and take you.”

Henry’s eyes darted toward the yard, where Old Mark was approaching. “I don’t… I don’t trust—”

“You trust living,” Samuel interrupted gently. “That’s enough.”

Old Mark examined the foot, then nodded once, grave. “It is dangerous,” he said. “But not hopeless. You will do what I say. You will rest. No walking. No stubbornness.”

Henry gave a weak laugh that turned into a grimace. “Aye. No stubbornness. I’ll try.”

Old Mark brewed a bitter tea from willow bark and other plants he gathered near the creek, and he made a poultice of crushed leaves and warmed resin that he packed against the wound. He changed it several times a day, washing the cut with clean water and insisting Samuel boil cloth before using it.

On the third day, the red streaks began to fade.

On the seventh, Henry stood again, shaking but whole, staring at his own foot as if it had been returned from the dead. He found Old Mark behind the house and, to Samuel’s quiet surprise, took off his hat.

“I was wrong,” Henry said, voice thick. “You saved my leg. Maybe my life.”

Old Mark didn’t swell with victory. He only nodded, as if humility was part of the medicine. “I used what I was taught,” he said. “A gift is not a gift if you hoard it.”

After that, the farm changed shape. Not in its fences or fields, but in its gravity. People started coming.

At first it was neighboring farmers arriving with sick children, wives with joint pain, men whose coughs wouldn’t leave. Some came sneering, as if they were doing Samuel a favor by allowing his “experiment” to entertain them. Most left quieter than they arrived. A fevered boy slept for the first time in two nights after Old Mark’s compress and tea. A woman’s swollen hands loosened enough that she cried, not from pain but from relief. A miner who’d been coughing blood found the bleeding eased with syrup and rest, and he swore he could finally draw a full breath.

Samuel, watching this steady parade, saw two truths at once. One was obvious: Old Mark’s knowledge worked far more often than it failed. The other was sharper: Hawthorne Ridge was willing to accept help from an enslaved man as long as it didn’t require them to respect him.

So Samuel did what the town understood. He built structure around it.

He converted a small shed into a clinic space with benches, a table, and shelves for jars. He began charging fees to the wealthier visitors and quietly treating the poor for little or nothing. And then, one evening as the sun bled orange across the fields, he sat with Old Mark and said the words that felt like stepping onto thin ice.

“They’ll keep coming,” Samuel said. “Your work could change things for both of us. I’ll take a portion to keep this running, but I want you to have a share too. Enough that… one day… you could buy your freedom.”

Old Mark looked at him for a long time. In the lantern light, his eyes held years that the law refused to count. “You offer a path I stopped believing in,” he said quietly. “Do you know how dangerous hope can be?”

Samuel swallowed. “I do. That’s why I’m not offering it lightly.”

Something in Old Mark’s posture shifted, small but unmistakable, like a door opening that had been sealed for decades. “Then I will work,” he said. “Not as a tool. As a man with purpose.”

As Samuel’s farm prospered, Hawthorne Ridge grew uneasy. Prosperity, when it arrives in the “wrong” hands, starts arguments. Colonel Baines, who had mocked Samuel in the square, showed up one afternoon with his hat held too tight in his fists, his face strained with fear.

“My daughter has a fever,” he admitted, the words tasting like humiliation. “Dr. Whitcomb says it’s… he says he’s done all he can.”

Samuel could have made him beg. He could have named a price that would have felt like justice. He pictured Anna, pale and sweating, while Dr. Whitcomb insisted leeches were the answer to everything. He also pictured the girl, innocent of her father’s cruelty.

Samuel simply nodded toward the clinic. “Bring her in.”

Old Mark recognized the signs quickly, the pattern of rash and delirium, the way fever sat on the child’s skin like a brand. He mixed teas, cooled her with herbal baths, and applied compresses that eased the heat. Three days later, the girl sat up asking for bread and laughing at nothing in particular, which was the sweetest sound in a room that had held death’s shadow.

Colonel Baines wept, awkwardly, as if tears embarrassed him. “How much do I owe?”

Samuel glanced at Old Mark, who gave the faintest shake of his head. Samuel answered, “Nothing. A child isn’t a bill.”

That mercy, far more than any miracle, turned heads. It made Hawthorne Ridge pause and realize Samuel Hart was not simply making money. He was rewriting rules, one quiet decision at a time.

And that was when Dr. Percival Whitcomb declared war.

He had been losing patients, prestige, and coin. A man like Whitcomb could tolerate poverty in others, but not disrespect toward himself. He began telling anyone who would listen that Samuel’s “African slave” practiced witchcraft, that his remedies were dangerous, that allowing an enslaved man to “play doctor” threatened the town’s moral order. He petitioned the local authorities, pushing for a ban, leaning on old laws and older prejudices.

Samuel felt the ground shift beneath his feet. The clinic had become a lifeline for people, but it could also become a noose if the sheriff decided to make an example.

One night Samuel sat with Old Mark, the clinic quiet, jars lined like patient sentries along the shelves. “They’ll stop us,” Samuel said, voice low. “Whitcomb has friends. If the county declares this illegal, everything we built… it’ll be gone.”

Old Mark didn’t answer immediately. He stared at a candle flame as if listening to it. Then he said, “There is a way. But you must trust me fully.”

“I already do,” Samuel said.

Old Mark’s eyes lifted. “Then hear me. We need a cure they cannot deny. Not in private. Not in whispers. In public. For someone important enough that the town must look straight at the truth.”

Samuel’s stomach tightened. “Who?”

Old Mark’s voice was simple. “Judge William Carver.”

The judge was the county’s heaviest stone, a man whose opinion could become law simply because people acted like it was. He was also known, quietly, for chronic back pain that bent him slightly when he thought no one watched. Dr. Whitcomb had treated him for years with bleeding and blistering plasters, and the pain had remained like a curse.

Samuel invited Judge Carver to dinner under the pretense of discussing a land dispute. The judge arrived stiffly, smiling with effort, accepting wine as if he needed it to carry the weight of his own body.

Midway through the meal, Samuel said carefully, “Your Honor, forgive me if this is improper, but I’ve noticed you move with discomfort.”

Judge Carver’s smile broke into weary honesty. “My back has been tormenting me for five years,” he admitted. “Some days I can’t rise without seeing stars. Whitcomb has tried everything. Leeches. Bleeding. Poultices that burn. None of it works.”

Samuel kept his voice calm. “I have someone here who has helped people with pain like that. If you’d allow him to examine you…”

The judge hesitated. He knew the rumor. He knew the controversy. But pain makes philosophers of proud men. It teaches them the difference between dignity and stubbornness.

“Call him,” Judge Carver said at last. “I’m tired of being a prisoner in my own bones.”

Old Mark entered with quiet respect. He asked questions that no one in town’s “educated” circles bothered to ask: where the pain began, what worsened it, what eased it, how the judge slept, how he worked, what he ate, what he carried in his body besides pain. He pressed gently along the judge’s spine and hips, listening not only to words but to flinches.

“I can help,” Old Mark said, “but not in one night. Three weeks. Three visits a week. Teas daily. Heat, oil, massage, and stretches you must do even when you do not want to.”

Judge Carver narrowed his eyes. “And if I do all this, and nothing changes?”

Old Mark’s gaze didn’t waver. “Then you may shut our doors yourself.”

The agreement was made like a wager with fate.

For three weeks the judge came at dusk, when the roads were quieter and fewer eyes lingered. Old Mark warmed stones wrapped in cloth, pressed heat where muscles clenched like fists, and massaged with oils infused with herbs meant to calm inflammation. He taught the judge small stretches that looked almost ridiculous for a powerful man to perform, but pain had already humbled him; he had room for a little more humility.

After the first week, the judge admitted grudgingly, “There are moments… brief, but real… when the pain loosens.”

After the second, he said, stunned, “It’s half what it was.”

After the third, Judge Carver arrived smiling, not the practiced smile of politics but the startled smile of relief. “I slept through the night,” he said softly. “For the first time in years.”

Samuel felt his knees nearly weaken. It wasn’t just victory. It was vindication, the kind that comes after long fear.

The following Sunday, after church, when Hawthorne Ridge gathered in the square to trade pleasantries and poison, Judge Carver stepped onto the courthouse steps and raised his hand. Conversations died instantly. Even the horses seemed to listen.

“Citizens,” he began, voice carrying authority like a drumbeat, “for five years I have suffered chronic pain in my back. Dr. Whitcomb, despite his best efforts, has not been able to relieve it.”

Dr. Whitcomb stood in the crowd, face already flushing.

Judge Carver continued, “Three weeks ago, I allowed the healer on Mr. Samuel Hart’s farm to treat me. The man you call Old Mark.” He paused, letting the name hang in the air like a question. “I stand here today to say plainly: he succeeded where our formal medicine failed.”

A ripple moved through the crowd, shock turning into murmurs, murmurs turning into something like awe.

Dr. Whitcomb tried to protest. “Your Honor, this is dangerous precedent! Allowing an enslaved man to practice—”

Judge Carver cut him off with a calm that was sharper than shouting. “Your diploma did not cure my pain, Doctor. His hands did. Results speak. From this day forward, I will not permit harassment or interference with Mr. Hart’s clinic. Those who seek help there will be protected under my authority.”

Silence followed, heavy and complete. It wasn’t the silence of agreement. It was the silence of people realizing their world had been forced to make room for a truth they had tried to laugh away.

After that, the clinic became a river in flood. People came from neighboring counties, sometimes traveling two days to sit on Samuel Hart’s benches and wait for Old Mark’s calm voice. Samuel hired an assistant to help with scheduling and supplies. He expanded the space. He kept the rule: the wealthy paid more, the poor paid what they could, and no one was turned away simply because they had empty pockets.

Exactly one year after the auction, Samuel invited Judge Carver, the local reverend, several respected farmers, and dozens of former patients to his home. In the parlor, with papers laid out on a table, Samuel stood and said, “A year ago, I paid six hundred dollars for a man everyone called useless. Many of you laughed. Today I’m here to do what I intended from the beginning.”

He turned to Old Mark, who stood straighter than he had that day in the sun, as if purpose had been slowly rebuilding his spine. “Your name,” Samuel said, voice clear, “is not Old Mark. You told me it once was Kambale Makori. I can’t return what was stolen from you, but I can stop being part of the stealing.”

Samuel lifted a document. “These are your manumission papers. Signed and witnessed. From this moment, you are a free man.”

For a heartbeat, the room held its breath.

Then Judge Carver began to clap, slow and deliberate. The reverend joined. Others followed until the sound filled the house like rain on a roof. Old Mark’s eyes shone with tears he didn’t try to hide. When he finally spoke, his voice trembled, not with weakness, but with a lifetime shifting its weight.

“You bought me as the law allowed,” he said to Samuel. “But you saw me as a man. You gave me back my name, my work, my dignity. I have lived many years without those things. I thought I would die without them.”

Samuel’s throat tightened. “Anna would’ve wanted this,” he whispered. “I’m only catching up to her courage.”

Samuel then offered another document. “I want to make you my partner. Not my servant. Not my possession. Equal share. Your knowledge, my land and management. We build this together.”

Some faces stiffened, discomfort rising. An ex-enslaved African man as an equal business partner was a revolution in a town that treated hierarchy like scripture. Judge Carver studied the papers, then looked up and said, “If we claim results matter more than pedigree, we must prove it when it costs us comfort.” He signed as witness.

And so the clinic became something rarer than a success story. It became a living argument.

In the years that followed, Kambale Makori, now called Dr. Makori by some and simply “Mr. Makori” by those learning respect, used his earnings in ways that made Samuel proud and made Hawthorne Ridge uneasy. He purchased the freedom of older enslaved people whom other owners considered “spent,” men and women with skills and knowledge that had been treated like scrap. A midwife with decades of experience. A blacksmith whose hands still shaped iron like poetry. A seamstress whose eyes were failing but whose fingers could still conjure miracles from cloth.

He opened a small school beside the clinic where he taught herbal knowledge and basic reading to anyone willing to learn, free or enslaved, Black or white, because he insisted that wisdom wasn’t a prize to be guarded. It was a fire to be carried.

In 1853, a young physician named Julian Forsyth arrived from Philadelphia, trained in newer methods, curious and unusually humble. “I have studied in hospitals,” Forsyth said, “but I’ve never seen the kind of outcomes people describe here. I don’t want to disprove you. I want to understand you.”

Makori smiled, the expression gentle and tired, like an elder seeing a younger man take the right posture before a lesson. “Then we will teach each other,” he said.

Forsyth taught anatomy and emerging European theories. Makori taught plants, observation, and the way illness often lived in the whole life of a person, not just in one aching part. Together they wrote careful notes, building a record meant to survive them.

When Makori’s health finally began to fail, it didn’t happen all at once. It came like dusk, gradual and honest. One autumn evening in 1858, he called Samuel into the clinic office, where jars lined the shelves like memory.

“I have no family here,” Makori said quietly. “My wife and children were stolen from me before I had gray hair. But I built another kind of family in this place. A legacy.”

Samuel swallowed hard. “Don’t talk like you’re leaving.”

Makori’s eyes softened. “We all leave. The question is what remains standing when we are gone.” He slid a paper across the desk. “Half of my share goes to you, because you chose to see me when others did not. The other half becomes a fund. Education for those society ignores, the way it ignored me. Let them become healers, teachers, builders. Let them carry the fire.”

Samuel’s hands shook as he held the paper. “You don’t owe me this.”

Makori shook his head. “I owe you nothing. This is not debt. This is purpose.”

Makori died in September of 1859, surrounded by Samuel, Dr. Forsyth, and several students who had once been considered worthless by the same laws that tried to erase them. His final words were simple, spoken like a blessing and a challenge.

“Tell them,” he whispered, “knowledge has no color. Value cannot be measured by the surface. Look deeper.”

His funeral drew crowds larger than Hawthorne Ridge had ever seen for any man, because grief has a way of exposing truth. Former patients stood beside people who once would not have shared a bench. The reverend spoke about dignity. Judge Carver, older now, said plainly, “This man was sold as property, but he lived as a teacher. If we learned anything from him, let it be this: the worth of a human being is not decided by age, strength, or the cruelty of a system.”

The years that followed tested the country with fire. War came. Emancipation finally became law. Hawthorne Ridge, bruised and changed like everywhere else, carried Makori’s story like a seed.

Samuel lived long enough to see the clinic become a proper hospital, staffed by Makori’s students and Dr. Forsyth’s apprentices, blending careful documentation with traditional remedies that had saved lives when pride could not. Samuel never remarried. When asked why, he would say, “I had one great love, and then I had one great partnership. Both taught me how to be a better man.”

In 1880, the town erected a statue in the square where the auction platform once stood. It showed Makori holding a bundle of herbs in one hand and a book in the other, not because he had been perfect, but because he had been proof. The inscription at the base read:

KAMBALE MAKORI (C. 1781–1859)

FROM ENSLAVEMENT TO FREEDOM, FROM DISMISSED TO INVALUABLE.

LOOK DEEPER.

Children grew up playing around that statue, and when they asked what it meant, parents had to decide what kind of truth they were willing to hand down. Some told it as a tale of medicine. Some told it as a tale of courage. The best told it as both, because healing, in the end, was never only about wounds. It was about seeing.

And somewhere in that seeing, Hawthorne Ridge finally understood what had silenced them on auction day. It wasn’t Samuel Hart’s money. It was his refusal to accept the town’s small, lazy definition of worth. He had spent six hundred dollars, yes, but what he had really paid was the price of stepping out of a cruel crowd and walking toward a different kind of future.

One man bought an old enslaved healer because he looked deeper. And in doing so, he reminded a whole town, and later a whole generation, that value is not a thing you declare over someone.

Value is a thing you recognize.

THE END

News

All Doctors Gave Up… Billionaire Declared DEAD—Until Poor Maid’s Toddler Slept On Him Overnight

The private wing of St. Gabriel Medical Center had its own kind of silence, the expensive kind, padded and perfumed…

Mafia Boss Arrived Home Unannounced And Saw The Maid With His Triplets — What He Saw Froze Him

Vincent Moretti didn’t announce his return because men like him never did. In his world, surprises kept you breathing. Schedules…

Poor Waitress Shielded An Old Man From Gunmen – Next Day, Mafia Boss Sends 4 Guards To Her Cafe

The gun hovered so close to her chest that she could see the tiny scratch on the barrel, the place…

Her Therapist Calls The Mafia Boss — She Didn’t Trip Someone Smashed Her Ankle

Clara Wynn pressed her palm to the corridor’s paneled wall, not because she needed the support, but because she needed…

Unaware Her Father Was A Secret Trillionaire Who Bought His Company, Husband Signs Divorce Papers On

The divorce papers landed on the blanket like an insult dressed in linen. Not tossed, not dropped, not even hurried,…

She Got in the Wrong Car on Christmas Eve, Mafia Boss Locked the Doors and said ‘You’re Not Leaving”

Emma Hart got into the wrong car at 11:47 p.m. on Christmas Eve with a dead phone, a discount dress,…

End of content

No more pages to load