Her mother, Lillian Hartley Vance, wore grief like a dress she eventually outgrew. Lillian was beautiful in the way people wrote poems about, and she lived as if the world owed her applause for simply entering a room. After Charles died, she took Evelyn with her from hotel to hotel, ship to ship, party to party, as if motion itself could keep sorrow from catching up.

In photographs, Lillian looked like the kind of woman who belonged to champagne. In person, she was laughter first and mother second. Evelyn learned early that if she wanted attention, she had to become either impressive or quiet. She mastered quiet because it required less permission.

She also learned, long before she understood interest rates, that adults spoke about her money with an intimacy they never used for her feelings.

“She has everything,” people would say in drawing rooms, while Evelyn sat nearby pretending to be absorbed in a book whose words she couldn’t hold onto.

Everything. The word landed like an insult.

What she had was a trust fund she couldn’t touch, a famous surname she couldn’t live up to, and a childhood spent as a traveling accessory in a glamorous life that did not make space for child-sized sadness.

When Evelyn was ten, her mother’s drifting finally collided with a force strong enough to stop it.

Beatrice Vance Hale.

Beatrice was Charles’s older sister, and she carried herself like a person who believed order was a moral virtue. She funded museums, collected art, hosted dinners that came with seating charts more complex than some governments. She spoke calmly, even when she was furious, because to Beatrice, losing control of her voice was the same as admitting defeat.

Beatrice watched Lillian’s perpetual movement and concluded, with the certainty of someone used to being obeyed, that Evelyn was being raised like luggage.

So Beatrice did what powerful people did when they wanted something they believed they deserved.

She sued.

The case exploded into the newspapers like a thrown glass. Reporters packed the courtroom. Photographers waited outside like hunters. Every detail, from the cost of Evelyn’s dresses to the tilt of her mother’s hat, became public entertainment.

They called Evelyn “the poor little rich girl.”

It was meant to be pity wrapped in a nickname. It felt, to Evelyn, like a label nailed to her forehead.

In the courtroom, adults argued over what was best for her, which schools she should attend, which tutors were appropriate, which household would safeguard her fortune. They said “stability” and “structure” and “proper environment” as if they were talking about a greenhouse, not a child.

Evelyn sat in a chair too big for her legs and listened to strangers describe her life as if she were absent.

The day she was asked to speak, the judge leaned forward kindly and told her she could be honest. Honesty, in that room, felt like a trap.

She glanced at her mother, whose eyes glittered with a kind of desperate charm, and then at her aunt, who sat perfectly still, as if emotion were something she kept locked in a cabinet.

Evelyn understood, with a clarity that made her stomach hurt, that both women loved her in ways that had more to do with themselves than with her.

She said what she thought would create the least damage.

“I want… to be somewhere quiet,” Evelyn whispered.

The courtroom interpreted it as wisdom. The newspapers called it heartbreaking. Beatrice’s lawyer wrote it down like a victory.

Beatrice won custody.

Lillian left the courthouse looking beautiful and furious, swearing she would return. She did not return in the way Evelyn, in her small hopeful corners, once imagined.

Evelyn was driven to Beatrice’s estate in a car that smelled like leather and decisions. The house was enormous, full of art and discipline and the kind of silence that came from expensive rugs absorbing footsteps. Evelyn was assigned a governess, a schedule, a room arranged like a display.

Stability arrived.

So did confinement, dressed in silk.

2. The House That Was Not Hers

Under Beatrice’s guardianship, Evelyn’s life ran on rails. Breakfast at eight. Lessons at nine. French and piano and posture and history delivered like medicine. A chaperone at every outing, a driver who knew exactly where she was supposed to go, a maid who laid out her clothes as if she were a doll being dressed by unseen hands.

Beatrice rarely raised her voice, which made her displeasure more frightening. When Evelyn did something wrong, Beatrice simply looked at her with mild disappointment, as if Evelyn had failed a test she should have known existed.

“You are a Vance,” Beatrice would say. “You must behave like one.”

Evelyn never asked what behaving like a Vance meant, because she was afraid the answer would be: behaving like you are not your own.

At night, when the house finally loosened its grip and the lamps dimmed, Evelyn would sit by her window and draw in a sketchbook she hid beneath her mattress. Faces, hands, swans, impossible flowers. She drew because in drawings she could create a world that listened to her. She could decide where the shadows went.

One evening, Beatrice found the sketchbook.

It happened quietly, the way disasters sometimes did in wealthy households. Evelyn returned from lessons and saw Beatrice in her room, sitting in the chair by the window. The sketchbook lay open on Beatrice’s lap.

Evelyn stopped breathing.

Beatrice turned a page. Then another. Her expression did not change, but Evelyn felt as if her ribs were being tightened one by one.

“These are… imaginative,” Beatrice said at last.

Evelyn waited for praise like a starving person waiting for crumbs.

Beatrice closed the book with a soft finality. “Art is fine,” she added, “as a pastime. Do not let it distract you from your responsibilities.”

“What responsibilities?” Evelyn asked before she could stop herself.

Beatrice looked at her, and for a moment Evelyn saw something almost like surprise, as if she had forgotten Evelyn might want to know the terms of her own life.

“Your education. Your reputation. Your future,” Beatrice said, listing them with the calm of someone naming furniture. “You will be prepared. You will be protected.”

Protected. The word fell between them like a locked door.

That night, Evelyn lay awake and tried to imagine what it would feel like to walk through a day without someone hovering nearby, correcting her posture, monitoring her tone, measuring her choices against an invisible standard.

She did not yet have language for it, but she was beginning to understand that protection could be another form of possession.

It was at one of Beatrice’s dinners, when Evelyn was sixteen and wearing a pale dress chosen by someone else, that she met Vincent DeMarco.

He arrived late, wearing a suit that looked like it had been argued into shape by tailors. He kissed Beatrice’s hand with practiced ease and then turned his attention to Evelyn with the focus of a man who had noticed the most valuable object in the room.

“You must be Evelyn,” he said, smiling as if they shared a secret.

Evelyn had been admired before, but admiration usually came with distance. Vincent’s attention was immediate, warm, adult. It made her feel seen in a way that bypassed rules.

“You look bored,” Vincent added softly, as if boredom were a rare jewel he had discovered.

“I’m not bored,” Evelyn lied.

Vincent’s smile widened. “You should be. All this is a museum with better food.”

Evelyn glanced toward Beatrice. Her aunt was speaking to a senator’s wife, her posture immaculate. She did not look at Evelyn.

Vincent leaned closer. “Do you want to leave?” he murmured.

Evelyn’s heart stumbled. “Leave where?”

“Anywhere,” Vincent said. “Somewhere you can breathe.”

It was the first time someone had offered her a door without asking Beatrice’s permission. Evelyn did not notice how carefully Vincent was watching her reaction, the way one watches a lock while turning a key.

Within months, the idea of leaving became an obsession Evelyn could not admit to anyone. It grew in her like a second heartbeat. Vincent wrote letters that smelled faintly of cologne and freedom. He sent invitations to Hollywood parties, describing a world where no one knew her as the child from the custody trial, where she could be new.

Beatrice disapproved, of course. She called Vincent “unsuitable,” which in Beatrice’s language meant dangerous and therefore irresistible to someone starving for agency.

Evelyn argued, quietly, carefully, the way you argue when you have been trained not to cause scenes. Beatrice resisted, equally quietly, and for weeks their conversations felt like a chess game played with smiles.

In the end, Beatrice did something Evelyn did not expect.

She allowed it.

Later, Evelyn would understand that Beatrice believed marriage would contain Evelyn the way a gilded frame contained a painting, keeping her safe and presentable. Beatrice likely imagined Evelyn would marry, settle, become predictable.

Evelyn imagined marriage would become her exit.

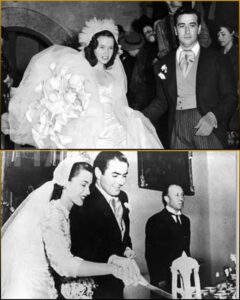

So the chapel in California happened, the pearls, the long train, the photograph that made Evelyn look like a girl stepping into a fairy tale.

What she stepped into was something else entirely.

3. The Beautiful Prison

Hollywood, in 1942, shimmered with illusion. Everywhere Evelyn looked there were lights, parties, people laughing too loudly because quiet might invite truth to sit down at the table. Vincent loved it. He moved through rooms like he belonged to them, shaking hands, trading favors, collecting secrets.

Evelyn watched, fascinated at first, as if she had been dropped into a moving picture.

Then the novelty wore off, and the rules revealed themselves.

Vincent wanted Evelyn to be beautiful and grateful. He wanted her silent when he spoke, charming when he needed her charm, invisible when he needed her to disappear. The attention he had offered her before marriage turned into scrutiny afterward, his admiration curdling into irritation when she did not behave as he expected.

If she spoke too much at dinner, he pinched her knee under the table. If she disagreed with him in private, he laughed as if she had told a joke.

“You’re a child,” he would say, smiling. “Don’t pretend you’re not.”

At first, Evelyn tried harder. She adjusted her tone, softened her opinions, tucked her feelings into neat corners. She thought if she learned the right version of herself, Vincent would return to the man who had offered her air.

Instead, he became more volatile, as if her compliance was a fuel that made him burn hotter.

One night, after a party where Vincent had introduced her to a studio executive’s wife and then ignored her for hours, Evelyn returned to their house and went to her small upstairs room where she kept her paints. She sat at the easel and began to work on a canvas of a swan, its neck arched, its eye sharp. The swan’s body was elegant, but the water beneath it was dark, almost violent.

Vincent appeared in the doorway.

“What is this?” he demanded.

“A painting,” Evelyn said, surprised by the tremor in her own voice.

Vincent stepped into the room, looked at the canvas, and then laughed. It was not a warm laugh. It was the laugh of a man who believed he had the right to ridicule whatever did not serve him.

“You’re wasting time,” he said. “I didn’t marry you so you could play artist.”

Evelyn’s hands froze. “I’m not playing.”

Vincent’s face tightened, and for a moment the mask slipped enough for Evelyn to see the anger underneath, raw and impatient.

“You don’t get to decide what you are,” he said. “You’re my wife. You’re a Vance. You’re a headline people watch. You will not embarrass me with this nonsense.”

Evelyn stared at him, at the man she had chosen because she thought he was a door, and she realized with a cold clarity that doors could close behind you, too.

After that night, the house felt smaller. Vincent began controlling things that seemed trivial but were not: when she ate, who she spoke to, whether she wrote letters, how long she spent alone. If Evelyn left the house without telling him, he accused her of ungratefulness. If she stayed, he accused her of sulking.

The world outside still saw the glamorous heiress, the beautiful young wife. Inside, Evelyn moved carefully, measuring her words, bracing for Vincent’s moods.

One afternoon, Evelyn caught her reflection in a mirror and did not recognize the girl staring back. She looked older than seventeen. Her eyes were too careful, like someone who had learned that joy was dangerous because it could be taken away.

That day, Evelyn sat on the bathroom floor with the door locked, listening to Vincent’s footsteps below. She pressed her forehead against her knees and realized she had escaped Beatrice’s control only to step into Vincent’s.

She had traded a cold cage for a heated one.

In the quiet, a thought arrived, soft and stubborn.

No one is coming to rescue you.

Evelyn lifted her head and looked at herself in the mirror again. She did not see a princess. She saw a girl with money and fear and a small, untested vein of defiance.

She decided to test it.

Leaving Vincent was not dramatic at first. It began with small preparations: a private meeting with a lawyer, money moved quietly, letters written and hidden, a suitcase packed when Vincent was out. Evelyn was terrified, but fear was no longer enough to keep her still.

When she finally told Vincent she was leaving, he stared at her as if she had spoken a foreign language.

“You can’t,” he said.

Evelyn’s voice shook, but she did not back down. “I can.”

Vincent’s smile returned, sharp and disbelieving. “You don’t know how the world works.”

Evelyn thought about the courtroom when she was ten, the reporters, the adults speaking over her head. She thought about Beatrice’s schedule, Vincent’s demands. She thought about her own hands holding a paintbrush, the only place she had ever felt like herself.

“I know how my world works,” she said quietly. “It stops today.”

She walked out.

The air outside did not feel like freedom immediately. It felt like exposure, like stepping into winter without a coat. Evelyn had never lived without someone else’s structure, someone else’s rules, someone else’s money as leverage.

She was alone, and loneliness still frightened her, but it also carried something she had never had before.

Possibility.

4. The Maestro Who Opened the Window

It was in New York, after the divorce papers began their slow grind through the legal world, that Evelyn met Adrian Wolff.

He was a celebrated conductor, famous enough that strangers recognized him in restaurants. He was also older, much older, with silver hair and eyes that seemed to hold entire symphonies. Evelyn met him at a benefit for an arts foundation, one of those events where people drank expensive wine and praised creativity as long as it stayed tasteful.

Evelyn stood near a wall, watching the room as if she were still learning the choreography of being unguarded. She had brought a small sketchbook with her, a habit she could not break, and when the speeches grew dull, she began drawing the profile of a man across the room, his face angled toward a violinist he was speaking to, his hands moving as if he were conducting even in conversation.

Evelyn did not realize Adrian had noticed until his shadow fell across her page.

“You draw as if you are listening,” he said.

Evelyn looked up, startled. “I’m sorry. I didn’t mean—”

“I’m not offended,” Adrian said, his tone almost amused. He glanced at the sketch, then back at her. “You see shape. Most people only see spectacle.”

Evelyn felt something in her chest loosen, the way a knot loosens when you finally admit it exists. “People have been seeing spectacle around me for years,” she said before she could stop herself.

Adrian studied her with the calm attention of someone who had spent a lifetime watching human emotion translate into music. “Then you deserve a place where spectacle is optional,” he said.

They spoke for the rest of the evening. Adrian did not ask about her money first, which felt almost miraculous. He asked about art, about what she painted, about what colors she loved. He listened as if her answers mattered.

When he invited her to a rehearsal, Evelyn accepted with a caution she did not fully understand. She had learned that men who offered doors sometimes offered cages.

Still, she went.

In the orchestra hall, the music rose around her like weather. Adrian stood at the front, his arms shaping the air, and Evelyn watched the way he commanded sound without shouting. It was power of a different kind: focused, disciplined, passionate.

Afterward, Adrian walked her out into the cold night. “You have an artist’s restlessness,” he said. “It will either destroy you or save you.”

Evelyn laughed softly. “Those seem like the only options in my life.”

“They are not,” Adrian said. “You can choose a third one. You can build.”

It was the word build that stayed with her, solid and heavy, the opposite of the drifting she had known.

Within a year, Evelyn married Adrian.

People talked, of course. They always talked. The age gap became gossip. Evelyn became a headline again, the rich girl trading husbands as if they were outfits. The commentary did not capture the reality, which was quieter and more complicated.

With Adrian, Evelyn felt encouraged. He did not mock her art. He praised it, challenged her, pushed her into galleries and studios and conversations with painters who spoke in metaphors. He wanted her to create, and for the first time in her life, someone’s expectations aligned with her own desire.

They had two sons, Leon and Sebastian, and Evelyn loved them with an intensity that sometimes frightened her, because love that large made you vulnerable to loss.

Life with Adrian was full of music, travel, beautiful chaos. Evelyn painted between rehearsals, wrote late at night, acted in small theater productions. She was, for a while, not just a surname.

She was a person making things.

Still, control has many costumes. Adrian’s was elegant, woven from admiration and authority. He was used to being listened to, and without noticing it at first, Evelyn found herself orbiting him. His schedule shaped their days. His moods shaped their evenings. His opinions, spoken gently, began to feel like invisible fences.

One morning, after an argument about a gallery show Evelyn wanted to do alone, Adrian sighed and touched her cheek.

“My dear,” he said, “you don’t need to prove anything. The world already knows who you are.”

Evelyn stared at him.

That was the problem.

The world knew who it thought she was.

Evelyn wanted to find out who she actually was, even if the answer disappointed people.

Leaving Adrian was harder than leaving Vincent, because Adrian had not been cruel. He had been supportive, even loving, which made Evelyn’s dissatisfaction feel like betrayal.

Still, she could not ignore the feeling that she was slowly becoming someone’s idea again, even if the idea was flattering.

When she finally told Adrian she needed to go, his face tightened with confusion.

“Why?” he asked. “We have everything.”

Evelyn swallowed. “We have your everything,” she said. “I need mine.”

5. The Director and the Mirror

By the time Evelyn met Jonah Lasky, she was no longer a teenager fleeing disaster. She was a woman in her early thirties with two children, a portfolio of paintings, and a reputation for reinvention.

Jonah was a film director with intense eyes and the restless energy of someone always cutting scenes in his head. He met Evelyn at a party thrown by writers who liked to smoke and argue. Jonah treated Evelyn like an equal from the beginning, not a novelty.

“You understand framing,” Jonah said after seeing her collages. “You think in scenes.”

Evelyn found herself stepping deeper into performance, into storytelling. She acted in television dramas, appeared on stage, learned the discipline of rehearsals where nobody cared about her last name. She loved it. Work felt like a kind of truth, because you could measure it.

Her marriage to Jonah became a partnership of ambition, art, late-night conversations. It was not a cage, but it was not home, either. Jonah’s world demanded focus, sacrifice, devotion to craft, and Evelyn discovered that she did not want to devote herself entirely to anyone’s universe, even one built from creativity.

When their marriage ended, it ended with sadness rather than scandal. They had tried. They had learned. They had reached the edge of what they could be together.

Evelyn did not collapse.

She had learned, over years, that leaving could be a form of survival.

6. The Love That Felt Like a Kitchen Light

Evelyn met Ethan Cooper not at a gala or a studio party, but at a bookstore.

She was browsing essays, half-hiding from the world. He was a writer with ink-stained fingers and a laugh that sounded like someone had taught it to be kind. Ethan spoke to her without ceremony, pointing out a book he thought she might like, and when she realized he had no idea who she was, she felt strangely relieved.

They talked for an hour between shelves. Ethan’s questions were simple in the best way. What did she love to paint. What did she fear. What did she miss from childhood. He listened without trying to solve her.

Evelyn fell in love the way people fall asleep: gradually, then completely.

Ethan did not try to mold her. He did not use her name as a ladder. He loved her in a way that felt like an open window.

They married in 1963.

Their home was not a museum. It was a place where socks appeared on stairs, where laughter interrupted conversations, where the kitchen smelled like tomato sauce and bread. They had two sons together, Cal and Andrew, and Evelyn watched Ethan become the kind of father she had never known: present, playful, steady.

The ordinary days became miraculous.

Evelyn still painted, still wrote, still acted now and then, but she did it without the ache of proving herself to someone else. Ethan cheered for her, the way you cheer for someone you adore, not the way you cheer for an investment.

For the first time, Evelyn felt something she had been chasing since childhood.

Safety.

Not safety as confinement, but safety as warmth.

7. The Scarf That Started Talking Back

In the early 1970s, Evelyn licensed her artwork for a line of silk scarves. It was meant to be simple: her paintings, printed on fabric, sold in department stores to women who wanted to wear something beautiful without needing permission.

The scarves sold quickly. Evelyn found herself fascinated by what happened when art became something people lived inside. A woman would wrap Evelyn’s colors around her throat and walk out into the day, carrying a piece of Evelyn’s imagination into an office, a subway, a dinner.

It felt intimate.

Then, at a meeting with a designer named Ravi Murjani and a sharp-eyed merchandising expert named Warren Hersch, someone mentioned a shipment of unused denim sitting in a warehouse overseas. It was the sort of detail most people ignored, an inventory problem, a footnote in a conversation about scarves.

Evelyn leaned forward.

“Why is it unused?” she asked.

Warren shrugged. “No plan for it.”

Evelyn imagined denim like a blank canvas, stiff, utilitarian, something meant for labor rather than beauty. She also thought of the women she saw everywhere now: working, moving, building lives that required clothes that could keep up.

“What if we make jeans for women,” Evelyn said, “that fit like they were designed for women, not borrowed from men.”

Ravi blinked. “Women already wear jeans.”

“They wear them,” Evelyn agreed, “as compromise.”

In her mind, an image formed with startling clarity: a pair of jeans cut close to the body, flattering without punishing, strong without being shapeless. A garment that didn’t apologize for curves, didn’t demand women hide their bodies or fight them.

A garment that said: you belong in your own skin.

Warren’s eyebrows lifted. “Designer jeans.”

Evelyn nodded slowly. The idea felt dangerous, which made it feel honest.

“Not just designer,” she said. “Personal.”

The men in the room began talking numbers, distribution, manufacturing. Evelyn barely heard. She was thinking of the swan she had painted years ago, elegant above dark water, surviving.

“We put my name on the pocket,” she said.

Warren hesitated. “That’s… bold.”

Evelyn remembered the courtroom, the headline, the way strangers had used her name to tell stories about her.

“This time,” she said, “my name belongs to me.”

They created samples. Evelyn insisted on stretch denim, fabric that moved with the wearer. She fought for sizes that included girls barely out of childhood and women whose bodies had lived longer stories. People warned her that “designer” should mean exclusive, that broad sizing would cheapen the brand.

Evelyn refused.

“I was excluded from my own life for years,” she said. “I’m not building another locked room.”

They chose a logo: a heron, elegant and watchful, a bird that stood tall in shallow water, patient and unafraid.

When the first jeans arrived, Evelyn held a pair in her hands and felt a strange emotion rise in her throat. The denim was sturdy, the stitching neat. On the back pocket, in clean script, her name curved like a signature on a painting.

Evelyn Hartley.

It was not inherited. It was created.

8. The Day the World Bought Her Back Pocket

The advertising executives wanted models. They wanted anonymity. They wanted the jeans to speak without Evelyn’s face, because faces aged, and faces risked scandal, and faces made investors nervous.

Evelyn listened, then shook her head.

“No,” she said.

They stared at her.

“You don’t understand,” one man began.

Evelyn smiled politely, the way Beatrice had taught her, then spoke with the steadiness of a woman who had outgrown being managed.

“I understand perfectly,” she said. “My whole life, people have spoken for me. If this is my name, then I will be the one to say it.”

The first commercial was shot in a studio lit so brightly it felt like daylight manufactured in a factory. Evelyn stood in front of the camera wearing the jeans, her hair styled simply, her posture relaxed in a way she had never been at seventeen.

The director asked if she was nervous.

Evelyn thought of Vincent, of Adrian, of Jonah, of Beatrice, of Lillian, of the courtroom, of the little girl who had wanted a quiet place.

“Yes,” she said. “That’s how I know it matters.”

When the camera rolled, Evelyn looked straight into the lens and spoke about the jeans not as an accessory, but as a statement.

Not a costume.

A claim.

The commercial aired.

The response was immediate, almost unreal. Department stores sold out. Phones rang. Orders flooded in. Women wanted the jeans because they fit, because they were flattering, because the signature on the pocket made them feel seen, as if someone had finally designed something with their bodies in mind rather than against them.

Evelyn sat in her office the next morning staring at the sales numbers, feeling a laugh rise in her chest that had nothing to do with parties and everything to do with relief.

The money that came in was enormous, yes, but what shook her was something else: the proof that her taste, her ideas, her stubborn insistence, had turned into something tangible.

For the first time, the wealth attached to her name did not feel like a chain.

It felt like a tool.

That evening, she went home and found Ethan in the kitchen making sandwiches for the boys. Cal was telling a story about school with dramatic hand gestures. Andrew, quieter, watched Evelyn with the intense eyes of a child who already noticed more than he said.

Evelyn leaned against the doorframe and watched them, her heart full in a way it had never been in a chapel.

Ethan glanced up. “How did it go?”

Evelyn walked over and kissed his cheek. “We sold out,” she said.

Ethan grinned. “Of course you did.”

Evelyn looked at her sons, the warm kitchen, the ordinary life that had once seemed like a fantasy, and she felt tears sting her eyes.

Later, when someone asked her what the success felt like, Evelyn answered with a line she had once read in a book of songs, because it captured the truth more cleanly than any business jargon could.

“Mama may have and Papa may have,” she said, “but bless the child who’s got her own.”

9. The Rip in the Fabric

Success did not make life gentle. It made it loud.

The brand expanded: blouses, shoes, fragrances, home goods. Evelyn’s name appeared everywhere, stitched into the world. There were meetings, legal documents, people who smiled too hard and spoke too sweetly. There were also mistakes, mismanagement, deals that turned sour. Evelyn learned that money earned could still be mishandled, stolen, argued over.

She fought when she needed to fight, with a resolve that surprised people who still wanted her to be the fragile heiress from old headlines. Evelyn had learned, through marriage and divorce and reinvention, that softness did not mean weakness.

Then, in 1988, life tore in a place no stitching could repair.

Cal, her first son with Ethan, was twenty-three years old when grief entered the house like a sudden storm. The details of that day became blurred in Evelyn’s memory, as if her mind refused to keep them in focus, but the feeling remained sharp: a drop beneath her feet, the world tilting, the unbearable realization that love could be severed.

There are losses that change your relationship with time. After Cal, Evelyn measured days differently. Morning became something you endured before you earned the right to collapse at night. Food became tasteless. Color became suspicious, as if joy were a betrayal.

Ethan held her, his arms tight around her, his voice low and steady even when his own grief broke through. Andrew, still young, moved through the house like a ghost learning how to be human again.

Evelyn thought of her childhood, the way adults had treated her pain as a spectacle. She refused to let Cal become a headline. She refused to let the loss be consumed by strangers as entertainment.

Instead, she did what she had always done when life became unbearable.

She made something out of it.

Evelyn wrote.

The memoir that emerged was not polished, not careful, not designed to protect anyone’s reputation. It was raw, honest, a mother’s grief laid down in ink so that it could be held, examined, survived. She wrote about love, about guilt, about the impossible task of continuing after your child is gone.

People told her it was brave. Evelyn did not feel brave. She felt like a person trying not to drown.

One night, months after Cal’s death, Andrew sat with her in the living room. He was old enough now to ask questions no child should have to ask.

“Does it ever stop hurting?” he asked quietly.

Evelyn looked at him, at the son who remained, at the boy whose eyes carried both childhood and the early shadow of journalism, the need to understand.

“It changes,” she said. “It doesn’t stop. It changes shape, the way waves change. You learn how to stand in it without letting it take you.”

Andrew swallowed. “How?”

Evelyn reached for his hand. “By loving anyway,” she said. “By telling the truth. By making something that helps someone else feel less alone.”

Andrew nodded slowly, and Evelyn saw him storing that lesson somewhere deep, where it would later become part of the man he grew into.

10. A Late-Life Miracle Called Curiosity

Years continued. Evelyn aged, as everyone did, but she did not become smaller. If anything, she became more openly herself, as if time had finally bored her into authenticity.

She painted. She assembled shadow boxes filled with tiny objects, fragments of memory arranged like dreams caught in glass. She wrote essays that made readers uncomfortable in the best way, because she refused to pretend she had lived a perfect life simply because she had lived a wealthy one.

In her nineties, someone convinced her to try a new kind of public life: a social platform where young people posted pictures and captions as if throwing messages into the ocean.

Evelyn, who had once been a child devoured by newspapers, found the idea oddly charming.

She began posting photographs of her art, her collages, her boxes, her thoughts written in neat lines. She did not curate herself the way Beatrice would have demanded. She posted whimsy alongside grief, color alongside confession.

Young strangers responded with love, with questions, with admiration that felt different from the old kind. They were not watching her like a spectacle.

They were listening.

Evelyn sat in her studio one afternoon, sunlight warming her hands, and scrolled through messages from people who said her work made them feel brave enough to leave a bad relationship, brave enough to start a business, brave enough to write, brave enough to keep living after loss.

For a moment, she closed her eyes and thought of the girl in the courtroom, ten years old, wishing for somewhere quiet.

She had not gotten quiet.

She had gotten something harder and better.

A voice.

11. The Last Photograph

Near the end, Evelyn returned often in memory to that black-and-white wedding photograph from 1941. The girl in it looked composed, elegant, trapped in a moment that was both an ending and a beginning. Evelyn no longer hated the photograph.

She saw it now as evidence of what she had survived.

On one of her last evenings, Evelyn sat with Andrew in her apartment in Manhattan, surrounded by paintings and boxes and the gentle clutter of a long creative life. Outside, the city hummed, indifferent and alive.

Andrew, grown now, asked her something he had been afraid to ask for years.

“Do you regret any of it?” he said. “The marriages. The headlines. The fighting.”

Evelyn considered the question with the seriousness it deserved. She thought of Beatrice’s control, Lillian’s glittering absence, Vincent’s cruelty, Adrian’s elegant authority, Jonah’s intensity, Ethan’s warmth, Cal’s loss, Andrew’s steady presence, the jeans, the heron, the art, the writing.

Regret was a tempting word, because it offered the illusion that life could be edited.

“I regret the pain,” Evelyn said finally. “I regret what I could not protect. I regret the days I believed I belonged to other people.”

Andrew nodded, eyes shining.

Evelyn reached out and touched his cheek, her hand light.

“But I do not regret becoming myself,” she added. “I fought for that. I built it. I earned it. Even when the world tried to make me a story, I learned how to be the one holding the pen.”

Andrew exhaled, as if he had been holding his breath for decades.

Evelyn smiled, small and genuine.

“Promise me something,” she said.

“Anything,” Andrew replied.

“Keep making things,” Evelyn said. “Truth, beauty, kindness. Whatever form it takes. That’s how we survive being watched. That’s how we turn pain into something that doesn’t only hurt.”

Andrew swallowed and nodded, his grip tightening around her hand.

“I promise,” he said.

Evelyn leaned back in her chair, surrounded by her own creations, the room softly lit, the air calm. Outside, the city kept moving, as it always had. Inside, Evelyn felt something she had been chasing since childhood settle into place.

Not perfection.

Not safety purchased by obedience.

Something quieter, deeper.

Ownership.

Not of money, not of pearls, not of headlines.

Ownership of her life.

And if someone somewhere pulled on a pair of jeans with a signature stitched on the pocket, if they looked in the mirror and stood a little taller, Evelyn liked to imagine they were not just wearing fabric.

They were wearing proof.

Proof that a person could begin as a headline and end as an author.

Proof that even the “poor little rich girl” could grow into a woman who belonged to herself.

THE END

News

The MILLIONAIRE’S BABY KICKED and PUNCHED every nanny… but KISSED the BLACK CLEANER

Evan’s gaze flicked to me, a small, tired question. I swallowed once, then spoke. “Give me sixty minutes,” I said….

Can I hug you… said the homeless boy to the crying millionaire what happened next shocking

At 2:00 p.m., his board voted him out, not with anger, but with the clean efficiency of people who had…

The first thing you learn in a family that has always been “fine” is how to speak without saying anything at all.

When my grandmother’s nights got worse, when she woke confused and frightened and needed someone to help her to the…

I inherited ten million in silence. He abandoned me during childbirth and laughed at my failure. The very next day, his new wife bowed her head when she learned I owned the company.

Claire didn’t need to hear a name to understand the shape of betrayal. She had seen it in Daniel’s phone…

The billionaire dismissed the nanny without explanation—until his daughter spoke up and revealed a truth that left him stunned…..

Laura’s throat tightened, but she kept her voice level. “May I ask why?” she said, because even dignity deserved an…

The Nightlight in the Tunnel – Patrick O’Brien

Patrick walked with his friend Marek, a Polish immigrant who spoke English in chunks but laughed like a full sentence….

End of content

No more pages to load