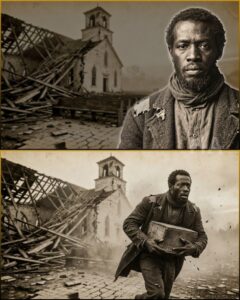

You learn early that a city can smile with all its teeth and still be starving for blood. In Calhoun Bluff, Louisiana, 1851, the river shines like a blessing and the cotton money shines like a threat, and the two get mistaken for the same thing. The mansions on River Street sit high above the docks as if altitude is morality. Bells ring on Sundays, and the sound travels over the slave pens the same way perfume travels over rot: pretty, persistent, dishonest. You are forty-two, an enslaved carpenter with hands everybody trusts and a name nobody says with love unless it’s whispered in the dark. In daylight, you are “boy” no matter how old your bones feel.

Your wife, Hannah, has a way of looking at you that keeps you from breaking, as if her eyes can hold your ribs together. Your son, Micah, is fourteen and built like tomorrow, long-limbed and restless, with questions tucked behind his teeth like contraband. He is the kind of bright that makes you proud and afraid at the same time. You teach him what you can, carefully, the way you teach a child to hold fire without getting burned. You teach him wood and weight, which beams carry truth and which boards exist only to impress. You teach him stories from across an ocean you barely remember, and you teach him the hardest lesson of all: how to look down without surrendering inside.

You also teach him how not to die. That lesson, you discover, is the one the world refuses to let him learn.

The church sits at the center of white Calhoun Bluff like a jeweled fist. St. Brigid’s, they call it, with columns meant to mimic Greece and a steeple meant to poke heaven until heaven looks back. It’s where the planters come in their best coats to prove to one another that God endorses their prosperity. The minister, Reverend Hollis Baird, has a voice like polished walnut and sermons that land soft as pillows, smoothing rough truths until nobody feels the splinters. Slavery, he says, is order. Order, he says, is mercy. Mercy, he says, sometimes requires a whip.

You have worked inside that building for months, hired out by your owner, Edmund Harrow, because your skill makes him money and your silence makes him comfortable. You move through the sanctuary before sunrise, alone with dust and candle wax, repairing what time has loosened. The building’s bones become familiar to you in a way people’s hearts never are. You know how the roof settles after rain, how the wood complains when the temperature drops, how the whole place hums when the organ shakes the air. You learn the church the way a captive learns the lock: not to admire it, but to understand it.

On April 15th, a Sunday that starts like any other, Micah comes with you. He carries tools and listens when you explain why a certain joint is strong and another is only pretending. He tries to be careful. He tries to be invisible. But invisibility is a costume that never fits a boy with pride in his posture.

The trouble begins outside, with hoofbeats and laughter and a manufactured anger that feels rehearsed. A young white man, Gideon Price, is the kind of man who believes the world was built as a mirror for his face. He claims Micah looked at him on the boardwalk. Two seconds, maybe less. Two seconds of accidental humanity, as if your son forgot the script for a moment. Gideon turns that moment into a public performance, shouting about “disrespect” the way a thief shouts “thief” to redirect the crowd.

You hear the commotion through the open church door and your stomach drops so fast it feels like gravity has learned your name. You step outside and see Micah in the center of it, surrounded, his shoulders pulled back as if refusing to fold. You move toward him on instinct, but Harrow’s hand clamps your arm. His grip is not just strong, it is confident, the grip of a man who knows the law lives inside his palm. “Don’t,” he says close to your ear, as if he is saving you. “You’ll make it worse.”

Worse than what, you want to ask. Worse than a world where a boy can be killed for a glance.

They drag Micah up the church steps, and the steps seem to remember every boot that has climbed them, every heel that has clicked like a verdict. Reverend Baird appears, robes neat, face composed, eyes already deciding that compassion is inconvenient today. You watch for a crack in him, a human hesitation, but he gives only a solemn nod. He speaks of obedience and correction, words that sound clean until you see what they are used to justify.

They tie your son to the railing that wealthy families steady themselves on when they arrive to worship. The same iron that helps them climb becomes a cage for a child. Gideon announces a number, then treats it like a suggestion. The whip is a language all its own, a language that says: you are property, you are beneath, you are permitted to suffer.

You try to move. You try to breathe. You try to become anything other than a man forced to watch.

Harrow and another man hold you. Their voices are calm because they are not the ones losing a son. “If you lunge,” Harrow says, “you’ll die. Then what will Hannah do?” He says it like reason. He says it like love. He says it like a blade slipped into a hand.

Micah does not scream long. At first he makes sounds you recognize, the sounds of a child still believing pain is temporary. Then the sounds change into something smaller, something that seems to retreat inward. When you look at his face, you see a strange dignity there, a refusal to give Gideon the satisfaction of begging. You see your own lessons in his eyes, and you hate yourself for teaching him how to endure.

When it ends, it doesn’t end with mercy. It ends with your son sagging, your name caught in his throat like a stone he can’t swallow. They cut him down. He crumples on the steps of the church, and the crowd disperses with the casualness of people leaving a picnic. Reverend Baird adjusts his sleeves. Gideon smiles the way boys smile when they kick a dog and nobody stops them.

You carry Micah back to the quarters with Hannah walking beside you, silent, not because she doesn’t feel, but because feeling has flooded her past sound. She holds him for hours, rocking the way she rocked him as a baby, humming a lullaby that once promised safety. Micah’s eyes find yours once, briefly, and in that look you feel something that ruins you: forgiveness. Not permission. Not approval. Just forgiveness, offered by a dying boy to the father who couldn’t stop the world.

When Micah goes still, the air in the room changes. It’s the same air, but it becomes air you will never trust again.

You close his eyes gently. You kiss his forehead. You stand up.

“I need to finish work at the church,” you say, and your voice sounds like yours, which is the strangest part.

Hannah’s gaze lifts to you, and there is terror there, and understanding, and a love so exhausted it can’t afford to argue. “Don’t go get yourself killed,” she whispers. “I can’t lose both.”

You touch her cheek. Your thumb finds the salt that finally escaped her. “You won’t lose me,” you say. “Not today.”

You do not tell her what else you mean, because if you say it aloud, it becomes a living thing in the room, and living things can be caught.

That night, while the plantation sleeps and the world pretends Micah never existed, you return to St. Brigid’s. You have keys because you have been useful. You let yourself in through a side door and climb into the dark upper reaches where the church’s voice becomes silent and its bones become honest. The attic smells of old wood and trapped heat. Your breath sounds too loud, so you learn to breathe like a shadow.

You stand there, surrounded by the structure you have been paid nothing to preserve, and you realize something that feels like a new kind of seeing. The church is not sacred. It is assembled. It is a thing made by hands. And what hands assemble, hands can unmake.

Over the next months, you become two people at once. In daylight, you are the dependable craftsman again, eyes lowered, shoulders humble, grief performed in a way that doesn’t frighten white people. You answer questions with “yes, sir” and “no, ma’am.” You do not mention Micah unless someone else brings him up, and even then you speak as if you are describing weather. You let them believe your pain is quiet and harmless.

At night, you are the father the world tried to reduce to a creature. You return to the church when you can, not every night, not in any pattern. You listen for dogs, for drunks, for footsteps. You move carefully, using your knowledge of wood and weight, of age and strain, in a way that keeps your hands steady even when your insides are shaking. You don’t think of it as rage, because rage is noisy and gets you killed. You think of it as work, measured and exact, the kind of work you have always done.

You never speak the plan aloud. You don’t carve it into conversation. You don’t let it live in your face. You let it live only in the private place behind your ribs where Micah’s last look keeps burning.

Sometimes, alone in that darkness, you try to imagine another ending. You imagine running. You imagine buying freedom with money you will never be allowed to keep. You imagine a miracle, a letter, a law, some sudden act of mercy from a nation built on cruelty. You imagine a world where Micah grows up, where he learns your craft and becomes better than you, where he builds something that outlasts pain.

Then you remember the church steps. You remember the crowd. You remember the minister’s calm. And the alternative endings collapse in your mind like paper in water.

By winter, Calhoun Bluff is eager for celebration, which is another way of saying it is eager for forgetting. Christmas arrives with ribbons and evergreen, with wealthy women competing over dresses and wealthy men competing over generosity that costs them nothing. They sing about peace while the slave market remains open. They speak of goodwill while families in the quarters count the missing names taken south.

You know St. Brigid’s will be full on Christmas morning, packed with the people who applauded correction and called it holy. That is not a coincidence you ignore. It is an invitation the world makes without understanding who is listening.

On Christmas Eve, Harrow gives you permission to do a “final check,” because he trusts your skill more than he fears your grief. The church is decorated, candlelight rehearsing warmth. You move through the sanctuary with your head bowed like a servant and your mind steady like a ledger. You climb once more into the upper darkness where the structure holds its secrets. You do what you believe you must do, quietly, without spectacle, without the kind of detail that would be remembered by anyone who survives.

When you climb back down, your hands feel strangely light, as if they have handed off a burden to gravity itself.

That night, you sit beside Hannah by the fire in the quarters. She stares into the flames the way a person stares at a doorway they cannot walk through. When you take her hand, she flinches at first, not from you, but from the world using touch as a weapon.

“Tomorrow’s Christmas,” you say.

She turns toward you slowly, as if the movement costs her. “Samuel,” she says, though that is not your name anymore, not in this version of the world, because you have decided to be someone else in your own story. “What did you do?”

You meet her eyes. In them you see Micah’s smile, the one that used to appear when he learned something new. “What needed to be done,” you answer.

For a long moment, she is only breathing. Then she asks, in a voice scraped raw, “Will they know it was you?”

“No,” you say. “They will call it age. They will call it fate. They will call it God.”

“And I’ll know,” she whispers.

“Yes.”

She squeezes your hand so hard it hurts, and you let it hurt because pain is sometimes proof you’re still here. “I won’t stop you,” she says, and the words sound like a confession. “I don’t know what forgiveness looks like for people like us. I only know what they took.”

Christmas morning breaks cold and bright. The sky is clean, the kind of sky that makes wickedness feel impossible, which is exactly why wickedness loves it. You tell Harrow you feel sick, because the truth would be too complicated for his imagination. He waves you off, generous in the lazy way people are generous when they don’t expect to pay.

You slip away along paths you’ve walked a hundred times, keeping to trees and fences and the edges of the world. You find a place where you can see St. Brigid’s without being seen, a small stand of trees where shadows gather like witnesses. From there, you can see the steps where Micah died. There is no stain left. There is no marker. Blood washes away easier than memory.

People arrive early, laughing, cheeks pink from cold and excitement. They climb the steps in their fine shoes, carrying presents for one another, carrying the assumption that the world is built for them. Reverend Baird greets them at the door like a man welcoming friends into his home. Gideon Price appears in a crisp coat, his face relaxed, as if he has never harmed anyone in his life. Harrow arrives with his family, his children chattering about gifts, and for a brief instant your stomach twists, not with pity, but with the complicated recognition that innocence is a seed that can grow into cruelty when planted in this soil.

The church fills beyond comfort, beyond caution. The organ begins, and the first hymn rises like a boast. You can’t hear every word, but you recognize the tune. The building vibrates with voices praising a savior born among the poor, praised by rich men who have made poverty a cage.

You wait.

Minutes stretch. Your mind tries to betray you with doubt. What if the building holds? What if nothing happens and you are left alive with this thing inside you, this thing that has already changed you? You feel your heartbeat in your throat. You taste copper where you’ve bitten your tongue without noticing.

Then you hear it: a sharp crack that doesn’t belong to music. It is brief, almost modest, the way the first tear in fabric looks small until it becomes a rip you can’t stop. Inside the church, heads will tilt up. Confusion will flicker. Someone might laugh nervously. Someone might whisper “probably nothing.”

And then the “nothing” becomes everything.

The roof begins to give. Not with a single dramatic thunderclap, but with a swift, merciless surrender. The sanctuary turns into motion, dust blooming, glass shivering, sound swallowing itself. For a few heartbeats, the world is only collapsing and the terrible truth that people are slow compared to gravity. The hymn turns into screaming, then into a silence so thick it feels like a hand over the mouth of the city.

When it is over, St. Brigid’s is no longer a church. It is broken wood, broken stone, broken certainty.

You stand very still. You expected triumph. You expected a rush. You expected to feel Micah’s spirit rise like a banner inside you. Instead you feel a hollowing, as if something has been completed and the completion has left you empty. You cannot make your face smile. You cannot make your face cry. Your body seems to forget what expression is supposed to mean.

People run toward the wreckage. Some claw at rubble with bare hands, screaming names, screaming prayers, screaming at God as if God is a person who can be convinced. Dust hangs in the air like winter fog. Somewhere under that mess, voices call out, then fade, then stop. You do not go closer. Not because you are afraid of being caught, though you are. Not because you are afraid of the dead, though you are. You don’t go closer because you already know what you have done, and seeing it up close won’t turn it into something else.

You think of Micah’s body on the steps and how the crowd dispersed. You think of Hannah rocking him and humming. You think of Reverend Baird’s calm nod. You think of Gideon’s grin. You tell yourself, this is the answer. This is the price.

But your heart doesn’t celebrate prices. Your heart only keeps receipts.

As the morning unfolds, a strange thing happens at the edges. In the smaller building where enslaved people have been forced to worship apart, heads turn. They heard the collapse, the sudden roar, the way a symbol fell. They come out cautiously, eyes wide, hands covering mouths. You see old men straighten, as if a chain inside their spine has loosened. You see women press fingers to their lips, not to suppress tears but to hide expressions that would be dangerous in the open.

They don’t know it’s you. Not for sure. And you do not tell them. But you can feel a current moving through them, something like understanding. Not joy, exactly. Not approval. More like a startled recognition that power is not as absolute as it pretends to be.

The white officials call it a tragedy. They call it an accident. They call it the consequence of age and crowding and poor construction. They do not look too hard, because looking too hard would mean admitting an enslaved man might have been capable of outthinking them. They prefer a universe where you are simple, where your grief is a dull instrument, where your mind cannot hold a long plan without dropping it.

You answer questions with the same quiet humility you have practiced your whole life. You lower your eyes at the right moments. You offer sorrow in the shape they expect. You let them believe you are a man who understands his place. They do not imagine a man like you could carry a map of a building in his head the way a general carries a battlefield.

In the quarters, Hannah waits. When you return, she reads your face the way she reads weather. She doesn’t ask what happened, because she already knows. She only asks, very softly, “Is it done?”

“It’s done,” you say.

She wraps her arms around you, and for the first time since Micah died, you allow yourself to shake. Your tears come hard and ugly, not like rain but like something breaking loose. Hannah holds you without saying you are right or wrong. She holds you because you are still alive, and because love, even wounded love, still reaches for what it can.

The days that follow are filled with funerals on the hill and whispered conversations in the dark. The planters mourn their own loudly. They do not mourn Micah at all. The city rebuilds its routines with the stubbornness of people who think tragedy is an interruption instead of a mirror. They speak of faith more than ever, as if saying the word can patch the hole in their certainty.

You keep living, which turns out to be its own punishment.

You cannot return to carpentry. When you pick up a tool, your mind fills with the sound of giving wood, with the moment structure stopped being structure and became consequence. Your hands that once built cradles and tables now feel like strangers to creation. You ask to be sent to the fields, to work that is brutal but straightforward. Harrow is gone now, replaced by heirs and paperwork, and the people who inherit you do not understand why a skilled man would choose harder labor. They agree anyway, because they do not see you as a person making a choice. They see you as property developing a quirk.

Hannah does not leave you. She also does not return to the woman she was before April. Some nights she wakes with a sharp inhale, eyes wild, dreaming of falling roofs and trapped children. You hold her until her breathing settles, and you say nothing because words are too small for what you both carry.

Years pass. War comes. Freedom is spoken of like a rumor at first, then like a threat, then like a sunrise that doesn’t ask permission. When emancipation finally arrives in your area, it does not arrive as a clean moment. It arrives tangled in hunger and uncertainty and the bitter knowledge that freedom does not resurrect the dead.

You and Hannah leave Calhoun Bluff. You do not want to live on land soaked in your son’s blood and your own choices. You travel to a town where nobody knows your face, where the river is still a river but the past doesn’t stand on every corner. You take work where you can. You are older now, and your back speaks in aches, but you are alive, and being alive means you are forced to figure out what to do with the rest of your days.

One afternoon, years into freedom, a neighbor asks if you can help repair a porch. The request is small, ordinary, almost insulting in its normalcy. Your first instinct is to refuse. Your hands have been weapons, even if no one knows it. Your hands have betrayed your love into something terrible. You fear what your skill can become.

But then you see a little boy watching you from the yard, curious, safe, holding a stick like it’s a sword and laughing because the world hasn’t taught him to be afraid yet. You feel a sudden ache so sharp it nearly folds you. Micah should have been that age. Micah should have lived to laugh about nothing.

You kneel. You pick up the hammer.

Your hand trembles once. Then it steadies.

You build the porch not as penance, not as redemption, but as a refusal to let the worst thing you ever did be the only thing your hands remember. Each nail you drive is a quiet argument with fate. Each board you set is a whisper to Micah that says: I am still your father. I am still trying.

Hannah watches from the doorway. When the work is done, she brings you water. Her eyes rest on your hands, and for the first time in years you see something soften in her, not forgiveness exactly, but a small easing of the grip grief has kept on her throat.

Late in life, you tell no one your secret. You do not seek applause. You do not seek absolution. You understand, with a clarity that hurts, that some truths are too heavy to place on another person’s shoulders. But you also understand that silence does not erase anything. It only locks it inside.

So you do one thing. You write Micah’s name on a piece of wood and you keep it close. Not as evidence. As prayer.

When you die, you do not die righteous. You do not die clean. You die as most people die, complicated, carrying both love and damage, carrying a story that no church sermon ever dared to tell. Your last breath tastes like river air and old sorrow, and your last thought is not of collapsing roofs or dead men in fine coats.

Your last thought is of a boy’s eyes, meeting yours for two seconds, forgiving you for being trapped in a world that demanded blood for a glance.

You whisper his name.

And the room goes quiet.

THE END

News

All Doctors Gave Up… Billionaire Declared DEAD—Until Poor Maid’s Toddler Slept On Him Overnight

The private wing of St. Gabriel Medical Center had its own kind of silence, the expensive kind, padded and perfumed…

Mafia Boss Arrived Home Unannounced And Saw The Maid With His Triplets — What He Saw Froze Him

Vincent Moretti didn’t announce his return because men like him never did. In his world, surprises kept you breathing. Schedules…

Poor Waitress Shielded An Old Man From Gunmen – Next Day, Mafia Boss Sends 4 Guards To Her Cafe

The gun hovered so close to her chest that she could see the tiny scratch on the barrel, the place…

Her Therapist Calls The Mafia Boss — She Didn’t Trip Someone Smashed Her Ankle

Clara Wynn pressed her palm to the corridor’s paneled wall, not because she needed the support, but because she needed…

Unaware Her Father Was A Secret Trillionaire Who Bought His Company, Husband Signs Divorce Papers On

The divorce papers landed on the blanket like an insult dressed in linen. Not tossed, not dropped, not even hurried,…

She Got in the Wrong Car on Christmas Eve, Mafia Boss Locked the Doors and said ‘You’re Not Leaving”

Emma Hart got into the wrong car at 11:47 p.m. on Christmas Eve with a dead phone, a discount dress,…

End of content

No more pages to load