Charleston liked to pretend it was born clean, as if the tide had washed the first stones into place and the city had simply risen, polite and prosperous, from the marsh. The older buildings told a different story when the light hit them right, a stubborn truth trapped in brick: this place was built by hands that were not allowed to own their own names. In a back room of the provincial archives, behind a door that smelled of salt and iron, there was a bundle of papers tied with faded ribbon, sealed by authority and by shame, the ink of a governor’s order pressed like a thumb over a wound.

Charleston liked to pretend it was born clean, as if the tide had washed the first stones into place and the city had simply risen, polite and prosperous, from the marsh. The older buildings told a different story when the light hit them right, a stubborn truth trapped in brick: this place was built by hands that were not allowed to own their own names. In a back room of the provincial archives, behind a door that smelled of salt and iron, there was a bundle of papers tied with faded ribbon, sealed by authority and by shame, the ink of a governor’s order pressed like a thumb over a wound.

In the summer of 1766, when the seal was finally broken, the clerk who opened it did not do so dramatically. He was a man who believed history was mostly receipts, mostly dates, mostly the dull language of inventory. Even so, he paused when he read the first line, because it named fourteen of the colony’s most powerful planters, and then, without mercy, it named their end. He kept reading because he had been trained to keep reading, and because the truth has a weight that bends even disciplined wrists. A woman’s name appeared on the page, spelled three ways by three nervous hands, as if the letters themselves were trying to slip out of responsibility: Espiranza, Esperanza, Esparansza de Lima.

The clerk had never met her, of course, and would have called her a slave in the casual way his world used that word, like a tool name, like a harvest term. Yet the pages refused to let her remain a tool. They gave her a voice, not in the polished speeches of a gentleman, but in a single phrase written down with visible hesitation, as if the quill had trembled while copying it: Justice burns slower than coal, but burns complete. The clerk read it twice, then a third time, because it sounded like a proverb and a warning at once, and because it carried the wrong kind of certainty for a person the colony claimed was nothing more than property.

To understand how a sentence like that could survive the centuries, you had to return to the moment when she first arrived, when her name was taken and replaced, when her future was shoved into a marketplace like a crate of sugar.

In September of 1701, the harbor was loud with the familiar noises of profit: chains clinking, men shouting, gulls complaining overhead, barrels rolling along planks. The Portuguese ship Santa Maria sat heavy in the water, its belly emptied in stages, as if the ocean itself was reluctant to let its cargo go. The cargo was human, and Charleston did not blush at the word. The colony was young and hungry, and it fed itself on rice grown in swamps by people whose lungs learned the taste of standing water before they learned the taste of freedom.

Among the one hundred and eighty souls brought off that ship was a woman of roughly twenty years, average in height, composed in a way that unsettled those who expected terror to make people frantic. She had dark eyes that held steady even when men tried to make them drop, and the scarification on her shoulders carried meaning in a language the auctioneers could not read. She did not cry loudly, and that was interpreted as weakness by men who needed to believe pain always made a person smaller. In the world she came from, silence could be a shield, and stillness could be a blade kept under cloth.

Her birth name had been spoken with respect in her village, followed by titles and blessings. She had been raised among councils, trained to listen before she spoke, taught that power was not always a shout. Her grandmother had placed leaves in her palm and asked her to smell, to recognize which plant soothed fever and which plant sharpened the mind, and she had learned the oldest truth of survival: the body is a map, and every map has vulnerabilities. When Portuguese raiders burned her home, killed her father, and dragged her people toward the coast, she watched the flames as if committing them to memory, because grief without memory was just noise, and she could not afford to be noisy.

In Charleston, she became an entry in a ledger, assessed like a horse. Edmund Greyfield purchased her for forty-two pounds sterling, an amount that pleased him because it made her feel expensive and therefore justified. He was a second-generation colonist who wore wealth like armor and cruelty like a family crest. He stood over six feet tall with pale eyes that made people feel examined rather than seen, and his estate north of the Ashley River had a reputation that traveled faster than his horses. The enslaved whispered about Greyfield the way people whisper about storms: not because whispers can stop weather, but because naming danger is one of the few freedoms left.

Greyfield’s previous house servant, an older woman named Sarah, had died after an “accident” that everyone understood without needing the story told properly. Greyfield needed a replacement who would be quiet, competent, and broken. The woman from the Santa Maria presented herself as quiet, became competent, and did not break in the ways he expected. The name he gave her was intended to be decorative, almost comic in its optimism, like a joke at her expense: Espiranza de Lima, a name that tasted of Catholic saints and Portuguese ports, a name meant to remind her who had taken her.

Her first months at Greyfield Estate were an education in American refinement’s uglier understructure. The main house was elegant, imported furniture arranged to prove distance from the wildness of the land, silver polished until it flashed like a challenge. Beyond the manicured views, the rice fields swallowed labor the way a mouth swallows breath, and the swamps bred mosquitos with a devotion that seemed personal. Overseers carried whips with the same ease they carried instructions, and Greyfield’s voice could change the temperature of a room without raising in volume.

Espiranza learned quickly that the plantation’s true heart was not the fields but the dining room. The rice was money, the money was power, and the power gathered monthly around a table like fat around a bone. Greyfield hosted the Rice Council, fourteen planters who believed themselves the colony’s spine. They met under candlelight and discussed prices, policies, punishments, and expansion with the calm precision of men describing carpentry. Their names were spoken with admiration in Charleston’s best rooms, yet in the quarters, those names were spoken the way you speak of diseases, careful not to invite them closer.

Espiranza served them wine. She cleared their plates. She watched their hands when they gestured, their mouths when they smiled, their eyes when they grew bored. She listened to them speak of “stock” and “breeding” and “seasoning” with the detached interest of men who had turned other people’s lives into arithmetic. She noticed how Marcus Sutton laughed when someone described breaking a “difficult” slave, how James Rutherford’s judge’s voice became warm when he discussed separation as a tool, how Henry Caldwell dropped the governor’s name like a stone into every conversation to measure the ripples. She learned who arrived early, who drank too much, who liked to show off, who liked to pretend restraint while enjoying the spectacle of dominance.

She also learned the estate’s rhythms, the small habits that made a powerful system vulnerable. Men who believed themselves untouchable grew careless around those they refused to recognize as human. They spoke freely in front of her because they did not consider her a listener with a future, only a pair of hands that carried trays. Every month, information spilled like wine, and Espiranza collected it without spilling a drop of her expression. She learned English quickly and pretended she did not, shaping her face into blank obedience because that was the mask the world demanded from her. Inside, her mind remained a room with locked drawers, each drawer labeled with a name, a cruelty, a date.

Years passed. Greyfield’s wealth grew. The Rice Council’s confidence grew with it, swelling into arrogance that made them sloppy. Espiranza grew into the role of an invisible witness so completely that even new overseers stopped noticing her, which gave her a dangerous kind of access. She moved through the house like smoke, and she kept her hope alive by feeding it small, careful portions: a remembered lullaby, a glance exchanged with another enslaved woman, a moment of quiet in the kitchen at dawn before the day’s demands arrived.

Hope became more than an internal ritual in the spring of 1715, when she met a man the ledgers called Boy Tom.

He did not look like a hero, because heroes are a luxury invented by people who can afford to believe in tidy stories. He was twenty-two, built for hard work, with a scar at his temple that suggested he had learned early what resistance cost. His real name, spoken in murmurs among those who trusted him, was Wame, a name that carried his mother’s language like a hidden coin. He had learned to read in secret, taught by a sympathetic overseer whose sympathy had not saved him from dying in a world that ate tenderness. Wame used his knowledge carefully, passing letters and numbers to others during Sunday rests, turning literacy into a quiet form of rebellion.

Espiranza first noticed him because he looked up when others kept their eyes down, not with defiance meant to be seen, but with alertness meant to understand. He was often loaned out for heavy labor, which made him a traveler in a landscape designed to keep enslaved people isolated. He collected faces, routes, rumors, patterns of patrols, and he stored them in his mind the way Espiranza stored council conversations. When they began speaking, it did not happen like romance in a novel, with sudden confessions and dramatic gestures. It happened like conspiracy, with caution, with coded songs, with small movements that meant more than words.

At first they shared only information. She described what she heard in the dining room, how the planters spoke of new regulations, of shifts in patrol schedules, of disputes with London that might distract attention. He described what he saw when he traveled: which plantation’s overseer drank himself asleep, which marsh path remained unguarded at low tide, which white trader in town had a conscience that could be purchased with the right appeal. Their conversations grew into something larger, a braided thing made of strategy and tenderness, because people who are denied dignity become experts at finding it in each other.

They built a network, slowly, like a spider builds a web in a corner no one bothers to clean. Messages moved through songs and gestures that looked harmless to those who did not know how to listen. A hymn in the fields could announce an upcoming meeting. A work chant in the kitchen could warn of a search. A shared glance in the market could confirm a safe contact. Over months, then a year, the network stretched across properties. Espiranza’s position gave her access to the colony’s high-level intentions; Wame’s mobility gave him reach.

They were not planning a simple escape for two. They were mapping a possibility that could pull dozens, then hundreds, toward Spanish Florida, where free Black communities existed in uneasy alliance with Spanish authority. It was dangerous, it was uncertain, it was the kind of plan that required patience and nerve, and patience had become Espiranza’s most sharpened tool. She knew the cost of moving too early, because she had seen rebels caught and broken publicly, their punishment designed as theater for those forced to watch.

Then, in March of 1716, a different kind of theater was announced in the dining room, and it was aimed at her body.

Edmund Greyfield, pleased with his own cleverness, told the Rice Council he intended to expand his breeding program, using selected women like livestock to produce what he called “superior working stock.” The men nodded, some amused, some approving, because the language of the table had long since abandoned shame. Greyfield named several women. Espiranza’s name was spoken without ceremony, as if it belonged to a chair or a plow.

She poured wine while her stomach turned cold, and she kept her face still because a crack in her composure would invite immediate suspicion. When she retreated to the kitchen, her hands moved automatically through familiar tasks, and the familiarity felt like mockery. She had survived by imagining a future that included ownership of her own body. Now the system was planning to erase even the internal space where she kept her humanity intact.

That night she met Wame at their hidden place near a fallen cypress tree, where insects filled the air with noise that could cover whispers. He listened, his jaw tightening, and the two of them stood with the kind of stillness that appears calm until you recognize it as restraint. Wame offered escape immediately, because he had already arranged a fragile opportunity: a Spanish trader in town, a smuggling route, a chance to reach St. Augustine within days. The proposal was not romantic; it was urgent. It was survival.

Espiranza refused, and the refusal did not come from pride. It came from the weight of fifteen years of listening to evil spoken casually, from the memory of her village burning, from the faces of children sold like furniture. She told him, in Portuguese, that running would save them but would leave the machine intact, and she had grown tired of letting the machine remain comfortable. She spoke of the Rice Council as a head that guided the colony’s cruelty, and she spoke of fear as the only language these men respected. Wame argued softly because he loved her and because he understood what capture meant. When he realized her mind had settled into its decision, he stopped arguing and began helping, because love under slavery often looked like cooperation in terrible plans.

The plan they refined was not reckless, and it was not improvisation. It drew on observation, on habit, on the arrogance of men who believed their victims could not think strategically. Espiranza did not have the luxury of weapons or a militia. She had access, timing, and knowledge of psychology. She also had an old understanding, passed through women’s hands and voices across generations: if you cannot defeat a fortress by force, you learn how its gates open, and you wait for the moment the guards stop paying attention.

Days before the June meeting, Espiranza received news that tightened everything into inevitability. Wame had been sold, purchased like equipment by James Rutherford, the colonial judge who spoke of law while violating every moral law that mattered. The transfer would take place after the council gathering. Espiranza understood what that meant in practical terms: their network would fracture, their communication would become nearly impossible, and her own movement would be restricted once Greyfield placed her under constant watch for the breeding program. The window that had been narrow became a crack about to seal.

On the last night before the meeting, she and Wame spoke long and quietly, compressing years of longing into a few stolen hours. He begged again, not with desperation but with that plain truth people offer when they are running out of time. She answered with the only promise she could make honestly: she would not let their lives be reduced to numbers without leaving a mark on the world that tried to erase them.

June arrived heavy with heat. The air on the coast did not merely warm; it pressed, it clung, it made breath feel owned by the weather. On the morning of June 23, 1716, Espiranza rose before dawn as she always did, and she moved through her chores with the same quiet competence that had made her invisible. That invisibility was her disguise, and she wore it with disciplined patience. She ensured the other domestic enslaved workers were assigned away from the center of the house late in the evening, spreading tasks in ways that seemed practical and routine. She made sure the kitchen was stocked and prepared for a long meeting, because long meetings demanded long meals, and long meals required the furnace.

The furnace was Greyfield’s pride, a hulking British import that could hold heat steadily for hours, turning coal into a reliable, controllable power. Greyfield liked to show it to guests as proof of sophistication. Espiranza had learned its moods through years of tending it, understood how its appetite could be fed and how its breath could be controlled. A furnace, like a man, performed according to the attention it received.

By afternoon, the planters began arriving in carriages and on horseback, filling the drive with the sound of wealth. They came dressed for authority, with boots polished, coats tailored, hats tilted at angles that suggested they belonged. Each greeted Greyfield as if he were a king hosting other kings. They did not greet the people who carried their baggage or held their horses or poured their drinks with any real acknowledgment, because acknowledgment would require admitting those people had minds.

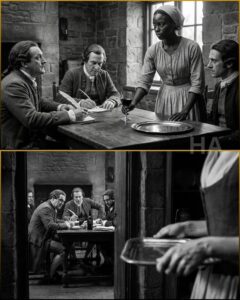

The meeting began on schedule. The men sat around the imported oak table, candles reflecting in glass and silver, the room arranged to flatter their sense of civilization. Espiranza served them with steady hands. She listened as they discussed rice prices and labor efficiency, and she noted the way the conversation always slid, eventually, into cruelty spoken like craft. They discussed “motivation” and “discipline” and “breeding registries” with the detached fascination of men describing animal husbandry. When the youngest, George Baxter, proposed selling older enslaved people to Spanish territories for profit, the room brightened with excitement, and Espiranza felt something inside her settle into a cold, quiet clarity.

Late in the evening, when the brandy had been poured and the men leaned into their chairs with the softness of those who believed themselves safe, Espiranza excused herself as she had done a hundred times, stepping out as if to retrieve more drink. The men did not watch her. They continued speaking of human lives as if discussing sacks of grain.

What happened next did not unfold like a brawl, because Espiranza had never intended a brawl. It unfolded like a trap closing, because she had spent fifteen years learning how these men moved and when they assumed no danger existed. The plan relied on the simplest weakness of the powerful: they never imagine consequences arriving from below.

One by one, conversation began to fray. Words slurred. Heads dipped. Hands that had signed orders and held whips trembled in confusion. At first the men blamed the heat, the liquor, the long day. Then the room tilted into alarm, and then, before they could gather themselves into coordinated action, the council’s confidence dissolved into unconsciousness.

Espiranza moved through the house with a focus so complete it felt, from the outside, like calm. She did not smile. She did not gloat. She worked as if completing an unpleasant necessity, because necessity is often ugly and rarely theatrical. In the kitchen, where chains and restraints were kept for the punishment of enslaved people, she used the tools of the system against the men who had designed it, binding them in ways she had seen used on others. She did not invent cruelty; she inverted it.

Hours passed. The estate stayed quiet because those who heard something understood the danger of being curious. A plantation at night is a place where silence becomes a currency, and everyone learns how expensive questions can be. Espiranza dragged the men into the kitchen, arranging them around the furnace as if creating a grim council meeting that could not be chaired by arrogance. When dawn began to thin the darkness at the windows, the men woke into a world that no longer obeyed them.

They tried to shout. They tried to command. They tried, at first, to believe it was a misunderstanding that could be corrected with threats. The bindings made their bodies uncooperative, and the heat made breath feel scarce. Fear entered them in stages, each stage stripping away a layer of identity they had built on dominance. They realized, finally, what helplessness tasted like, and that taste sickened them because it was unfamiliar and because it was deserved.

Espiranza sat at the kitchen table with a knife and a stone, sharpening the blade with slow, steady motions that made the sound of preparation, not hysteria. She hummed the lullaby her mother had once used to soften nightmares, and the song did not belong in that room, which made it feel like an omen. When she spoke, it was not in the broken English she had pretended to own. It was clear enough to cut.

She addressed them by name, not to prolong their suffering with speeches, but to deny them the comfort of anonymity. She spoke of acts they had committed, of families severed, of bodies punished, of human beings reduced to entries in ledgers. The men who had believed themselves architects of the colony discovered that someone had been studying their blueprints. Espiranza did not describe herself as righteous. She did not claim God had appointed her. She simply named cause and effect, the way a storm names a coastline.

The end of the fourteen men came with the furnace’s relentless heat and the long hours that followed, and the details were not recorded in full, not because they were merciful, but because even the officials who later wrote the report could not stomach placing every moment into ink. What survived in the archives was the shape of the scene: charred remains, arranged like a deliberate message, hands bound, mouths stuffed with raw cotton, the coal furnace still radiating a dull, exhausted warmth as if it had been forced to do work beyond its intended purpose.

When the other enslaved workers found the kitchen, their reaction was not celebration. It was shock, dread, and a quiet understanding of what this would bring down on them. Espiranza remained at the table, knife still in hand, her posture composed in a way that did not match the enormity of what had happened. When the overseers arrived, white and armed and suddenly uncertain, they saw something they could not fit into their worldview: a single enslaved woman, calm in the center of a catastrophe that had erased fourteen pillars of their society.

They tried to make sense of it by imagining witchcraft, because witchcraft was easier than admitting intelligence. They tried to make sense of it by imagining madness, because madness was easier than admitting logic. Yet the truth, the one that made their throats tighten, was simpler and more terrifying: she had planned. She had waited. She had learned. She had acted with the same methodical care they admired in themselves.

Governor Robert Johnson convened an emergency council in Charleston, not out of grief for the men, but out of fear for what their deaths implied. The plantation system relied on a particular story: enslaved people were incapable of sophisticated organization, incapable of deep planning, incapable of thinking beyond obedience. Greyfield’s kitchen had turned that story into ash.

The governor faced a dilemma that exposed the colony’s moral rot. A public execution of Espiranza would require public explanation. Public explanation would become public legend. Public legend would move through quarters and fields faster than any printed proclamation. A legend of successful resistance was a kind of fire the authorities could not control.

So they chose secrecy dressed as governance. The records were sealed. The official explanation offered to the planters’ families was a “tragic fire,” the kind of tragedy that did not require uncomfortable questions about why enslaved people might seek revenge. Espiranza’s sentence was designed to erase her without allowing her to speak. She was to be sold “south,” to Spanish mines where survival was rare and silence was almost guaranteed. The sentence was not justice. It was containment.

Three weeks later, on July 15, 1716, she was placed aboard a Spanish trading vessel, the Santa Isabella, with dozens of others whose names were not considered relevant. The ship moved on the evening tide, slipping past Charleston’s shoreline as if sliding out of a story that the colony wanted to lock away. The captain’s log, preserved neatly, later claimed that Espiranza died of fever on the third day and was buried at sea. The language was routine, clean, made for bureaucrats who preferred their deaths simple.

The enslaved, however, spoke of other possibilities, because the enslaved lived in a world where official truths were often convenient lies. Some said Espiranza had made contact with free Black sailors in the harbor long before the massacre, men who could move through port spaces with a kind of precarious autonomy. Some said she had traded knowledge for help, offering routes and names and plans in exchange for a chance to reach Spanish Florida alive. Some said Wame, sold away but not broken, had used the transfer chaos after the council’s deaths to slip into the port and into the shadowed spaces where men with keys did not look. In those stories, Espiranza did not die of fever. She vanished.

Whether she vanished through careful rescue or through sheer luck remains uncertain, because uncertainty is one of the few shelters oppressed people can build. What is certain is what happened after Greyfield, because the colony could not fully hide its tremor. The Rice Council meetings ceased. Planters began traveling with armed escorts. Routines changed. Doors gained locks. Masters who had once walked their properties with casual arrogance began scanning faces they had previously ignored, suddenly aware that a person carrying a tray might also be carrying memory.

Across plantations, incidents multiplied. A kitchen fire here, suspicious and fast. A prized horse dead there, poisoned by something that left no obvious trace. An overseer injured at the exact moment he was alone. Tools missing, then reappearing in places that suggested hands had moved them with intention. None of it was large enough to declare rebellion openly, but together it formed a pattern that made the powerful nervous.

Fear, for some, became a lever that shifted behavior. A few owners eased punishments, not because their hearts softened, but because their survival instincts sharpened. Others tightened cruelty, believing terror would smother resistance, and those plantations saw an opposite effect: more escapes, more sabotage, more quiet rage hardened into action. The colony responded with laws restricting movement and gatherings, trying to legislate control over people who had already learned how to speak without speaking.

And somewhere south, in the humid edges of Spanish Florida, there were reports of escaped people arriving with unusually detailed knowledge of South Carolina’s plantation patterns, people who could describe patrol schedules, identify sympathetic contacts, and move as if guided by an unseen hand. Free Black communities like Fort Mose became not just refuge but resistance infrastructure, stitched together by rumor and need. In those places, a woman with Portuguese on her tongue and a lullaby in her throat was said to tend to the sick, teach the young, and speak of strategy the way elders speak of weather.

In that version of her life, she did not spend her remaining years seeking more blood. The fire at Greyfield had been her message, and she understood that a message, once delivered, could not be delivered again the same way without losing its force and its meaning. Instead she turned her knowledge toward escape, toward survival, toward building something that did not rely on cruelty. She taught people which plants soothed fever and which plants helped a body endure long marches. She taught them how to watch a guard’s boredom, how to read a man’s arrogance, how to move information through ordinary behavior like water through cracks in stone.

When someone asked her, years later, whether she regretted what she had done, she did not answer quickly. Regret is a complicated word when your life has been built inside a cage. She spoke instead of cost, because cost was the truest language she knew. She said that violence always demands payment, sometimes from those who deserve it, often from those who do not. She said that the world had left her very few doors, and she had chosen the door that led through fire because the others led back into silent erasure. She said she did not believe she was a saint. She believed she was a human being who refused to be treated like livestock forever.

The lullaby she hummed remained the same one her mother had sung, and in Spanish Florida it became a strange kind of inheritance. Children who had never seen Greyfield learned the melody, not because it was pretty, but because it carried a reminder: your story can outlive the people who tried to own it.

Back in Charleston, the sealed papers waited, aging in darkness while the colony grew into a nation that would one day argue, then bleed, then change. When the archive seal broke in 1766, the clerk finished reading and sat quietly for a long time. He had expected history to be orderly. He had not expected history to be a woman with steady hands and a sentence sharp enough to slice through two centuries of silence.

He did not know what to do with the story. He could not praise it without admitting the sin that birthed it, and he could not condemn it without confronting the daily violence the colony called normal. So he did what institutions often do when confronted with a truth that makes them look ugly: he filed it away again, not resealing it with a governor’s order, but burying it beneath newer crises, newer wars, newer narratives that allowed people to avoid the older ones.

Yet stories do not stay buried forever, not when they fit too tightly inside the mouth of a lie. The Greyfield ashes remained in rumor, in whispered warnings, in the nervous way certain families avoided talking about that summer. They remained in the way enslaved parents taught their children to watch, to remember, to understand that the people who called themselves masters were not gods, only men, and men had vulnerabilities.

In the end, the most human part of Espiranza’s legacy was not the furnace, terrible as it was. It was the refusal to accept the colony’s definition of her as an object. The system had tried to reduce her to labor, to breeding, to silence. She answered with planning, with language, with memory, with a message that forced the powerful to recognize the minds they had tried to deny.

If you walk today along Charleston’s older streets, you can find plaques that praise founders and merchants, names etched cleanly into metal as if wealth were its own virtue. The archives, quieter and more honest, hold different names, many of them missing, many of them erased. Espiranza de Lima’s name survives crookedly, misspelled in places, because the hands that wrote it down did not respect it enough to learn it properly. Even so, it survives.

That survival is not an endorsement of what happened in Greyfield’s kitchen. It is a reminder that the true horror began long before the fire, in the daily, normalized brutality that created a world where a woman could see no path to dignity except through devastation. The humane ending, if there is one, is not that fourteen men died. The humane ending is that the lie of absolute power cracked, and through that crack, people began to imagine escape, resistance, and eventually a future where no one could be legally owned.

Justice does burn slowly sometimes, and it rarely burns neatly. The tragedy of Greyfield is that it took fire to make the powerful feel fear, when compassion should have been enough. The lesson that outlived the smoke was simpler than any governor’s decree: property can think, and when thinking is punished long enough, thinking learns how to become a weapon.

Somewhere, beyond the reach of ledgers and seals, a lullaby continued, carried in voices that refused to disappear.

News

All Doctors Gave Up… Billionaire Declared DEAD—Until Poor Maid’s Toddler Slept On Him Overnight

The private wing of St. Gabriel Medical Center had its own kind of silence, the expensive kind, padded and perfumed…

Mafia Boss Arrived Home Unannounced And Saw The Maid With His Triplets — What He Saw Froze Him

Vincent Moretti didn’t announce his return because men like him never did. In his world, surprises kept you breathing. Schedules…

Poor Waitress Shielded An Old Man From Gunmen – Next Day, Mafia Boss Sends 4 Guards To Her Cafe

The gun hovered so close to her chest that she could see the tiny scratch on the barrel, the place…

Her Therapist Calls The Mafia Boss — She Didn’t Trip Someone Smashed Her Ankle

Clara Wynn pressed her palm to the corridor’s paneled wall, not because she needed the support, but because she needed…

Unaware Her Father Was A Secret Trillionaire Who Bought His Company, Husband Signs Divorce Papers On

The divorce papers landed on the blanket like an insult dressed in linen. Not tossed, not dropped, not even hurried,…

She Got in the Wrong Car on Christmas Eve, Mafia Boss Locked the Doors and said ‘You’re Not Leaving”

Emma Hart got into the wrong car at 11:47 p.m. on Christmas Eve with a dead phone, a discount dress,…

End of content

No more pages to load