No one who stood beneath the tin awning of the New Orleans sale yard on that damp March afternoon in 1856 ever forgot the moment the girl called Isabella stepped onto the platform. The crowd had been loud a second before, men laughing too hard, boots scuffing sawdust, cigars glowing like small cruel eyes in the fog of breath and smoke, but her presence pinched the noise down to nothing. She was twenty-six, with light-brown skin that caught the weak sun as if it carried its own lamp, and black hair gathered low at the nape in a knot that couldn’t hide the weight of it, the length of it, the stubborn shine of it. Her eyes were a calm brown that did not beg. They simply looked, as if she were watching a distant shoreline and waiting for the water to decide what it wanted from her.

The auctioneer, a man who could sell a life as easily as a sack of flour, cleared his throat once, then again, then a third time, as if his own voice refused to cooperate with what he meant to do. “Gentlemen,” he said, forcing brightness into his tone, “a special offering today.” The men leaned forward. A few women in the back, wives who had come to select new hands for kitchens and nurseries, stiffened with the familiar mixture of curiosity and dread. Isabella stood still, hands folded, shoulders straight, the hem of her plain white cotton dress brushing her ankles like a whispered warning. When the first bid snapped through the air, the sound carried farther than it should have in that yard, and when the numbers began to climb, it felt as though even the river beyond the district had paused to listen.

At twelve thousand dollars, the world seemed to hold its breath. That was the sort of money that bought whole tracts of land, herds, reputation, a man’s future written in ink. It was not money spent on a person unless a person had already been turned into a legend. In the silence that followed, a cane tapped once against the platform post, deliberate as punctuation. The bidder had not raised his hand with excitement. He had done it with the weary certainty of someone placing a stone on a grave.

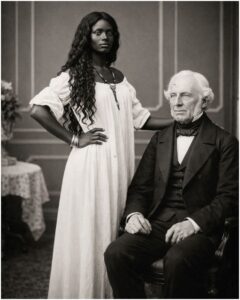

The man was Colonel Nathaniel Hartwell, forty-eight years old, broad-shouldered in a black coat that looked too formal for the muddy yard, his hair more gray than he probably wanted, his eyes sunk in shadows that weren’t made by the brim of his hat. When the hammer finally came down, it sounded less like a sale than a door locking. A few men whistled under their breath. Others stared as if they had just watched someone throw a fortune into the Mississippi and call it charity. Hartwell did not smile. He only held the auctioneer’s gaze until the clerk began pushing papers forward, and then he turned away as if he had already decided he would regret everything about this morning.

By sunrise the next day, on the far side of the city where the roads turned to packed earth and the air began to smell of wet cotton and old wood, he would know that the regret was real. But it would not be for the reasons anyone in that yard imagined.

The Hartwell plantation sat outside Vicksburg, Mississippi, where the land rolled gently and the cotton fields spread like a pale, endless argument with the sky. Folks called it Magnolia Ridge, though there were more magnolias near the big house than in the fields, planted to soften the view and perfume the air so visiting eyes could pretend they weren’t looking at suffering. The property had grown over decades, stitched together acre by acre, until it held nearly eight hundred acres of cotton and corn, worked by over two hundred enslaved people housed in rows of cabins spaced along the treeline. The main house rose two stories, white columns, deep porch, ironwork railings that caught the afternoon light like jewelry. It looked, from a distance, like a place where music should spill out of open windows and children should race down stairs. It looked, in other words, like a lie.

Inside, it was quiet enough to hear grief breathing.

Hartwell had married at twenty-five, in the way men with land and family names were expected to marry: to a woman whose lineage matched his ambition. Eleanor Marsh Hartwell had been bright, competent, the kind of hostess who could rescue an awkward dinner with a single sentence and a smile. Together they had produced two children, a son and a daughter, and for fifteen years Magnolia Ridge had played its part in the theater of Southern prosperity. Guests came. Candles burned late. Silverware clinked. The house staff moved like careful ghosts through rooms full of laughter. Then, in the summer of 1848, yellow fever rolled up from the river like a sentence from God that nobody could appeal.

Eleanor fell first. Ten days of fever and delirium, her skin burning, her eyes searching the ceiling as if she could find a door there. Hartwell sat beside her bed until his own body felt made of stone, listening to her whisper names that belonged to childhood, to places he’d never seen. Their son, Thomas, fifteen and still awkward in his limbs, tried to be brave until the fever climbed him too. He died holding his father’s hand, the grip tightening not in anger but in terror, as if he thought he could pull himself back into the world by sheer will. Their daughter, Caroline, twelve, lasted one terrible day longer, calling for her mother in a voice that cracked and faded until it became a sound Hartwell would later hear in his dreams even when he swore he was awake.

Three coffins. Three white crosses. One old oak at the family plot behind the house, thick enough to cast shade like mercy. Hartwell watched the dirt fall and felt something inside him go silent. It wasn’t simply sorrow. It was the sudden understanding that the life he had built had been balanced on people he loved, and without them the rest of it looked like a large, expensive mistake.

The eight years after the epidemic were not a healing. They were an occupation. Hartwell worked because work kept his hands moving and left his mind less room to wander into the rooms where Eleanor’s laughter used to be. He expanded fields, bought neighboring parcels, stored wealth he no longer had anyone to inherit it. Invitations piled up and died unopened on his desk. He stopped traveling to the city. He stopped inviting anyone in. Magnolia Ridge became a place where servants stepped softly and spoke in whispers, as if the whole house were a church with a coffin at the altar.

It was his overseer, Lucius Brewer, who finally broke the pattern.

“Colonel,” Brewer said one evening in early March of 1856, standing in the doorway of Hartwell’s study with his hat in his hands, “we’re short on hands for the next harvest. There’s a sale in New Orleans. Folks say some of these are the last shipments coming in through the gulf routes before the laws tighten again. We need to look.”

Hartwell didn’t lift his head from the ledger. “Send someone.”

Brewer shifted, stubborn in a way he rarely was. “You should go yourself. People take you serious. They won’t cheat the weights or hide the sickness when you’re the one looking.”

Hartwell’s pen paused. In the quiet between them, the house seemed to breathe, old wood settling, distant voices from the quarters riding the night air. “You want me out of my own home,” Hartwell said flatly.

“I want you alive in it,” Brewer answered before he could stop himself, then swallowed hard as if he’d tasted his own audacity. “Begging your pardon, sir.”

Hartwell should have thrown him out for that. Instead he stared at the ink on his page until it blurred. There were days when he felt like a man who had already died and simply forgotten to lie down. Finally he stood, reaching for his coat as if it belonged to someone else. “Fine,” he said. “We’ll go.”

The trip to New Orleans took three days by carriage and riverboat, and Hartwell filled the hours with silence. He traveled with a driver and two armed men, not because he feared bandits more than most planters did, but because wealth made a man visible, and visibility invited trouble. When they reached the city, the streets smelled of damp brick, fish, spilled beer, and the sweet rot of the river. Hartwell took rooms at a hotel near the Garden District, a place with clean sheets and polished floors that tried to pretend the city’s filth could not climb its walls. That night he stared out at the dark trees and wondered why he had agreed to come, as if he didn’t already know the answer: because Brewer had named the truth, and because Hartwell had been tired of haunting his own life.

The next morning, he rode to the sale yard with a perfumed handkerchief pressed against his nose. The market was crowded, men in heavy coats and muddy boots, merchants with careful smiles, clerks holding pens like weapons. People were lined up and examined like animals, muscles tested, teeth checked, scars noted with the same disinterest one might bring to counting barrels. Children were grouped and priced with the cold arithmetic of convenience. Hartwell moved through it all with a dull, practiced detachment, as if he had put his soul on a shelf years ago and forgotten to retrieve it.

And then he saw Isabella.

She stood apart from the main group, not chained in the same way, guarded by a trader who watched her like he watched his money. There were five other women with her, dressed more cleanly than the field hands, their hair arranged, their faces scrubbed. “House girls,” Brewer murmured beside Hartwell. “Luxury stock. Folks use them for entertaining, for showing off.”

Isabella did not look like she belonged to a category. She looked like a person trapped inside a category that was too small to hold her.

Hartwell felt something in his chest shift, not quite desire, not quite pity. It was closer to hunger, but not for her body. For movement. For sensation. For the strange proof that he could still be startled by life. The trader noticed his gaze and stepped forward, lips curling into a professional grin. His name was Étienne Dupré, French by birth or by performance, broad in the middle, rings on his fingers.

“You have an excellent eye, Colonel,” Dupré said, voice slick with confidence. “She is… exceptional.”

“Where did she come from?” Hartwell asked, pointing with his cane as if distance could keep him clean.

“Born in Louisiana,” Dupré replied. “Raised in a fine house in New Orleans. Her mother served there. The master had… attachments. He saw to her education. Reading, writing, sums, even some French. Then he died. Debts. The legitimate family sold everything.” Dupré shrugged like weather. “A shame, but business.”

“How much?”

Dupré’s grin widened. “For you, considering quality, twelve thousand.”

It was absurd. With that sum Hartwell could have purchased an army of field hands. Brewer’s eyes widened, a silent plea for sanity. But Isabella lifted her gaze at that moment, just once, and met Hartwell’s eyes with a steady look that held neither pleading nor gratitude. It held only recognition, as if she had seen men like him all her life and had decided long ago she would not be surprised by them again.

“Done,” Hartwell said, and hated himself for the speed of it.

The bidding at the yard was for show, a legal performance to put the sale in the books, but Dupré made Hartwell play it out anyway, perhaps to protect his own reputation. Two other planters tried to compete, their bids rising like taunts. Hartwell outbid them with the calm of a man tossing coins into a fire, and when the hammer fell, the yard went still. Isabella was his.

By evening, she rode out of New Orleans in Hartwell’s carriage, not shackled like the others, sitting opposite him with her hands in her lap, looking out the window as the city’s gas lamps faded into swamp-dark roads. Hartwell attempted to read a newspaper. The words refused to assemble into meaning. His eyes kept lifting, stolen glances he tried to disguise as boredom, studying the curve of her cheek, the unshaken line of her mouth, the way her posture refused to bend even when the wheels hit ruts.

For two days they did not speak. Silence became a third passenger, heavy and watchful. On the third night, they stopped at a roadside inn where the air smelled of stew and woodsmoke, and Isabella finally broke the quiet with a question delivered like a blade laid gently on a table.

“Why did you buy me?” she asked.

Her English was clean, educated, the kind spoken in parlors, not fields. Hartwell’s hand tightened around his glass of whiskey. “You’re… beautiful,” he said, because lying would have been easier but felt cowardly. “And I need someone to manage the house.”

“Lie,” she replied without raising her voice. She looked at him then, fully, eyes steady. “Men like you don’t spend fortunes on a woman to have her scrub floors. You bought a fantasy. A living doll to fill the empty rooms where you buried your family.”

The words landed in him with a sick accuracy. Hartwell’s face warmed, anger and embarrassment wrestling. “Careful,” he warned, because that was what his world demanded he say.

“I am careful,” she answered, and there was a tiredness beneath her composure, a weariness that sounded older than twenty-six. “That is why I’m telling you now: I am not a doll, Colonel. And you will regret this. Soon.”

Hartwell should have punished her. That was the rule. But punishment felt suddenly childish, like throwing stones at a storm. Instead he leaned forward slightly, caught by the strange honesty of her defiance. “Then tell me,” he said, voice low, “what will make me regret it?”

Isabella’s mouth curved, not in humor but in something sharper. “You’ll find out tomorrow morning,” she said. “Sleep while you still can.”

They arrived at Magnolia Ridge on the afternoon of March twenty-second. The quarters quieted as people turned to watch the carriage roll past. New acquisitions usually went straight to the overseer’s yard, sorted, assigned, absorbed into the machinery. Hartwell did not do that. He stepped out first and offered Isabella his hand to help her down. The gesture stunned his own staff. He saw it in their eyes: confusion, suspicion, a flicker of fear, because when a master behaved unpredictably, everyone paid for it.

He called for Martha, the older woman who managed the main house. Martha had served Eleanor, had held Caroline’s hair back when she was sick, had watched Thomas grow from a baby into a boy who would never be a man. She arrived quickly, gray hair wrapped in a scarf, eyes sharp.

“Prepare the guest room upstairs,” Hartwell ordered. “Isabella will stay there.”

Martha’s eyebrows lifted, but she said only, “Yes, Colonel,” and went.

Hartwell turned to Isabella. “Dine with me tonight. Eight o’clock. I want to know who you are.”

“As you wish,” she replied, but her eyes carried that same quiet promise that had chilled him at the inn.

Dinner was served in the formal dining room for the first time in years. Candles were lit. Silver was polished. The act felt like resurrection performed by hands that weren’t sure they believed in it. Isabella ate with careful grace, using utensils as if she had spent her life doing so. Hartwell poured wine and watched her, uncertain whether he was looking at a miracle or a trap.

“Dupré said you can read,” he began. “Write. How did that happen?”

Isabella set down her fork. “My mother worked for a lawyer in New Orleans,” she said. “He was a man who believed education was a kind of virtue, even when he denied humanity to the people around him. He decided a child of his blood, even born in bondage, should not be ignorant. So he paid for tutors. I learned letters, numbers, French phrases. I learned how to speak in rooms that never intended to welcome me.”

“And then?”

“He died,” she said simply, as if death were a door that always opened on schedule. “His wife inherited debts. She sold everything. My mother was sent upriver to a plantation. I was sold three times in four years.” Her voice did not tremble, but something dark moved behind her eyes. “Men wanted what men want when they buy women. You understand.”

A discomfort spread through Hartwell, hot and sour. “I did not buy you for that,” he said quickly, too quickly.

Isabella tilted her head. “Then why did you buy me, Colonel?”

He stared into his wine as if answers might float up. “Loneliness,” he admitted. “Eight years in a house full of ghosts. I saw you and… felt something. I don’t know what. Life, maybe.”

“Life,” she repeated, tasting the word like it might be spoiled. “It’s strange what the living call life when they build it on the backs of the dead.”

She rose. “May I retire? I’m tired.”

“Yes,” Hartwell said, standing automatically as if she were a guest, not property. “Sleep well.”

At the door, Isabella paused, turning just enough for her profile to catch the candlelight. “You asked why you would regret this,” she said. “You’ll learn in the morning. Sleep while you can.”

Hartwell slept poorly. When he did drift off, he dreamed of Eleanor’s hands on his cheeks and woke to the taste of dust in his mouth, as if the graveyard had crawled into his bed. At three in the morning he gave up on sleep and went to the library, sitting with a book he could not read. He waited for dawn the way a man waits for a verdict.

When the sun finally rose, thin and pale over the fields, Hartwell stepped onto the porch and watched the first workers walk out toward the cotton rows. The morning should have been ordinary. Instead, a scream cut through the house from upstairs, sharp and terrified, followed by the frantic thud of footsteps.

Martha ran past him, face drained of color. “Colonel!” she gasped. “Upstairs!”

Hartwell took the steps two at a time. The guest room door stood open. Martha was pressed against the hallway wall, one hand over her heart as if trying to keep it from escaping. Hartwell pushed into the room and stopped so abruptly his breath caught.

Isabella stood in the center, wearing a thin white nightgown, hair loose around her shoulders. In her hands was an old pistol, the barrel pressed against her own temple. Her finger curled on the trigger with a steadiness that made Hartwell’s stomach lurch.

“Don’t come closer,” she said. Her voice shook now, the first crack in her composure. “I warned you.”

“Isabella,” Hartwell whispered, lifting his hands slowly as if approaching a wild animal. “Put it down. Please.”

“Please,” she echoed, bitter. Tears slid down her cheeks, catching the morning light like tiny knives. “I’m tired. I’m tired of being sold. Tired of lying in beds waiting for doors to open. Tired of pretending this is life. I won’t do it anymore.”

“You don’t have to,” Hartwell said, throat tight. “I swear it.”

“All men swear,” she said, laughing once, broken. “And then they take what they paid for.”

Hartwell stepped forward a fraction, keeping his voice low. “I can free you,” he said, and felt the words leap out before he fully understood them himself. “I can give you papers. Manumission. Today.”

Isabella froze. Hope flashed in her eyes like a match struck in darkness, fragile and dangerous. “You lie,” she breathed. “No one spends that kind of money to free me the next day.”

“I’m not no one,” Hartwell said, and hated the arrogance of it even as he needed it to be true. He swallowed hard. “I lost my family eight years ago. Since then I’ve been living like a man buried standing up. I bought you because I wanted to feel something. But not this. Not your fear. Not your death. If the price of my loneliness is your life, then it’s too expensive.”

The pistol trembled. Isabella’s shoulders shook as she fought herself. “Why should I believe you?” she whispered.

“Because I have nothing to gain by lying now,” Hartwell said. “If I wanted to force you, I would have done it already. I don’t want that. I want… someone in this house to be here by choice. Even if only one person.”

For a long moment, the only sound was Isabella’s ragged breathing and Martha’s muffled sob behind Hartwell. Then Isabella lowered the pistol slowly, as if the air were thick and fighting her. It slipped from her hands and clattered to the floor. She dropped to her knees and folded forward, sobbing like a dam finally breaking after years of pressure.

Hartwell knelt beside her, not touching, simply being there, the way he had wanted someone to be there for him when Eleanor died and the world kept turning as if nothing had happened. It took a long time for Isabella’s crying to quiet into shudders, then into exhausted silence.

When she finally lifted her face, her eyes were swollen, raw. “You’ll really do it?” she asked, voice barely there.

“Yes,” Hartwell said. “I’ll send for a lawyer in town. We’ll file the papers. I’ll pay whatever it costs.”

“And then where do I go?” she asked, the question suddenly small. “I have no one. Nothing.”

Hartwell looked around the room, at the expensive furniture, the clean curtains, the house that had been a tomb. “You can stay,” he said. “Not as property. As a paid house manager. You’ll have your own room, your own wages, your own decisions. Stay until you decide what you want.”

It was scandalous. It was dangerous. It was, in their world, nearly unthinkable. But Hartwell felt something inside him unclench, as if a fist he had carried for years had finally opened.

Isabella studied him for a long time, searching for the familiar hooks of manipulation. Then she nodded once, slow. “All right,” she said. “I’ll stay.”

The legal work took longer than Hartwell wanted. Mississippi did not make freedom easy, especially not for a Black woman without family protection. Lawyers demanded fees. Clerks demanded stamps. Neighbors demanded explanations. Hartwell paid and signed and argued until the papers were in Isabella’s hands, thick with official seals, proof fragile as parchment but powerful enough to change the shape of a life.

The news traveled faster than the ink dried. Planters rode out to Magnolia Ridge under the pretense of neighborly concern and left with eyes narrowed, voices sharp. At church, women leaned toward one another and whispered behind gloves. Men laughed as if scandal were entertainment.

“He’s gone soft in the head,” one said.

“He’s bewitched,” another insisted, making superstition a mask for their own discomfort.

Lucius Brewer approached Hartwell in the barn one afternoon, face tight. “Colonel,” he began carefully, “people are talking. They say you’ve set a bad example. The hands will get ideas.”

Hartwell’s jaw tightened. “The hands have always had ideas,” he replied. “We’ve just ignored them.”

Brewer stared, unsure whether he was hearing compassion or madness. “It’ll make discipline harder,” he warned.

“Then we’ll stop mistaking cruelty for discipline,” Hartwell said, and surprised himself with the steadiness of it.

Isabella moved through the big house like someone reclaiming stolen space. She reorganized staff schedules, insisted on proper meals, aired out closed rooms, opened curtains that had been shut for years. She brought small signs of life back into Magnolia Ridge: fresh flowers in vases, clean linens, repaired shutters. Some of the enslaved women watched her with awe and suspicion, unsure whether her freedom meant she had joined the masters or escaped them. Isabella did not pretend her papers erased the past. Instead she spoke quietly in kitchens and hallways, her tone careful.

“I’m still me,” she told a young maid one night, when the girl asked if Isabella would now look down on them. “The paper didn’t change what they did to us. It only changes what they can do next.”

The truth was, Isabella’s presence forced Hartwell to see his own plantation with new eyes. He had always known, in some distant intellectual way, that slavery was brutal. But knowledge was a fog until a person you could speak to walked into it and began naming what was hidden. Isabella did not scream at him. She didn’t need to. She asked questions that burrowed under his skin.

“How many families have you separated?” she asked once, gently, over supper.

Hartwell set down his fork. “I… don’t know.”

“Then you never had to,” Isabella said, and the calm of it hurt worse than accusation.

He began making changes that angered Brewer and baffled neighbors. Work hours shortened slightly. Severe whippings were forbidden. Families were allowed to stay together. On Sundays, the quarters were left alone, no surprise inspections, no forced labor. Hartwell told himself these were practical choices, ways to keep peace, ways to avoid trouble. But late at night, he stood at the family graveyard and admitted to Eleanor’s silent stones that he was trying to become someone she might still recognize.

The bond between him and Isabella grew the way roots grow, slow and unseen until one day you realize they’ve cracked the stone. They spoke in the evenings, sometimes about books Isabella remembered, sometimes about the river, sometimes about nothing at all. Hartwell found himself laughing once, startled by the sound as if it belonged to another man. Isabella watched him as if she were witnessing an animal long believed extinct.

“Do you miss them?” she asked one night, meaning Eleanor and the children.

“Every day,” Hartwell said.

She nodded. “So do I,” she admitted, and for the first time he understood she wasn’t only speaking of her mother. She was speaking of herself, the girl she might have been if life had not demanded she become iron.

Their closeness, however, did not make the world kinder. It made it more dangerous.

One humid afternoon, a neighboring planter named Silas Granger arrived uninvited, two men with him. Granger was known for his temper, for his belief that the world belonged to whoever held power hardest. He stepped onto Hartwell’s porch like he owned it.

“I hear you’ve got a free colored woman living in your house,” Granger said, voice loud enough for servants to hear. “That legal?”

“It is,” Hartwell replied, keeping his tone mild.

Granger’s eyes slid past him, searching. “Where is she?”

“In my home,” Hartwell said. “As an employee.”

Granger smiled, thin. “That paper of hers will get challenged. Folks are saying the filing was irregular. A woman like that can’t just become free and stay on a plantation without stirring trouble. She’s property. Even if your paper says otherwise, the wrong man might decide it doesn’t matter.”

Hartwell felt anger rise, sharp and clean. “Are you threatening her?”

“I’m warning you,” Granger said, shrugging. “We’re on the same side, Colonel. Men like us keep order. You break the rules, you invite chaos.”

“We don’t have the same idea of order,” Hartwell answered.

Granger’s smile vanished. “Be careful,” he snapped. “There are people who’d rather see that woman back on a block than walking around with a book in her hand like she’s equal.”

“Then let them try,” Hartwell said quietly, and the stillness of his voice made Brewer shift uneasily behind him.

Granger left, but the threat stayed, hanging over the house like storm heat. Isabella heard about the visit before nightfall. She did not panic. She did not cry. She only looked at Hartwell with a hard, tired understanding.

“This is why I didn’t believe you,” she said softly. “Because even when you do the right thing, the world punishes you for it.”

Hartwell stared at the dark fields beyond the porch. “Then we’ll take the punishment,” he said. “Together, if you’ll let me.”

Isabella’s mouth tightened. “I don’t know how to trust,” she admitted. “But I know how to survive.”

“That’s a start,” Hartwell said.

Years moved like heavy wagons, slow but unstoppable. In 1860, whispers of war thickened into certainty. By 1861, boys marched off with shiny buttons and naïve pride, and the South braced itself like a man convinced he could fight time. Hartwell did not join the cheering. He was older, and grief had already shown him what victory cost. Still, the war came to him anyway, as war always does, arriving in letters and shortages and rumors carried by riverboat.

During those years, Isabella became more than a house manager. She became a kind of compass, pointing Hartwell toward choices he had avoided for decades. When enslaved men asked for permission to find wives on neighboring plantations, Isabella argued for it. When mothers begged not to have children sold, Isabella stood in Hartwell’s study and said, “If you mean anything you’ve done, you’ll refuse.” When Union troops came near the region and men began slipping away into the night to seek freedom behind blue lines, Isabella did not call them thieves. She called them brave.

Hartwell watched people leave and felt the plantation system cracking like old wood. Brewer raged about loss and discipline, but even he couldn’t deny the truth: slavery was dying, and it deserved to. The death, however, was not gentle. It was violent and chaotic, and it threatened to crush everyone beneath it, guilty and innocent alike.

In 1863, after the Emancipation Proclamation rippled through the country like lightning, the quarters buzzed with fear and hope tangled together. Some people didn’t believe it. Some believed too hard and got hurt. Isabella walked among them like someone carrying a lamp through a cave.

“Freedom isn’t a door that opens once,” she told them. “It’s a road. We’ll walk it, but we’ll walk it with eyes open.”

When the war ended and the Thirteenth Amendment finally nailed slavery’s coffin shut in 1865, Magnolia Ridge changed in a way Hartwell could not have imagined ten years earlier. Formerly enslaved families did not vanish overnight. Many stayed because the world beyond the plantation was hostile and hungry, and because leaving without money or land felt like trading one trap for another. Hartwell offered contracts, pay, and shares of crop profits that were fairer than his neighbors’ agreements. Some called him a traitor. Some called him a fool. Isabella called it a beginning.

The “marriage” people had whispered about in earlier years did not happen in the way society recognized. Mississippi would never have blessed it, and Hartwell knew that forcing Isabella into an illegal arrangement would only hand enemies another weapon. Instead, in 1866, they traveled quietly north to a place where they could live with fewer knives at their backs. In a small town beyond the reach of local gossip, they stood before a minister who did not ask for permission from anyone else’s hatred and made vows that were, at last, chosen.

When they returned to Magnolia Ridge, the world did not suddenly accept them. Many never did. But within the boundaries of their land, something rare took root: a household not built on ownership, but on decision.

They had children, three of them, raised in a house that still carried the shadows of its past but no longer pretended those shadows were normal. Hartwell grew older, slower, his hair white, his hands trembling slightly when he lifted a cup. Isabella’s face softened with time, but her eyes never lost their watchfulness. She had survived too much to become careless.

Hartwell died in 1894, as Eleanor’s epidemic year had once seemed impossibly far away. He was eighty-six, lying in the same bedroom where grief had once kept him prisoner. Isabella held his hand as his breathing thinned. He looked at her with a clarity he hadn’t possessed in years.

“I’m sorry,” he whispered.

“For what?” Isabella asked, though she knew.

“For thinking I could buy life,” he said. “For being part of a world that sold you. For needing your suffering to wake me up.”

Isabella squeezed his hand, firm. “You can’t undo what was done,” she said. “But you can decide what you do with what’s left. You did.”

And then Hartwell was gone, leaving behind a farm, a family, and a story the county would repeat with twisted details for generations: the colonel who paid the highest price at auction and regretted it by morning.

Isabella lived until 1912, old enough to see grandchildren running across fields that were no longer worked by chains. In her final years, she liked to sit on the porch at sunset, watching the land turn gold and shadow, listening to the sound of people talking freely, loudly, without fear of being punished for joy. Sometimes a younger relative would ask, quietly, about the morning long ago when she had held a pistol to her head.

“Do you regret not pulling the trigger?” they would ask, voice trembling as if the question itself might break her.

Isabella would smile, small and distant, and shake her head. “Every day,” she would say, “I’m grateful I hesitated one second longer.” She would look out at the fields, at the world that had changed too slowly and yet still changed. “Because in that second, I learned something. Even in the darkest places, a human choice can crack the wall. Sometimes that crack becomes a door.”

Her story was never meant to be a fairy tale. There were no clean heroes in it, no perfect redemption. There was a system that made monsters out of ordinary people and made merchandise out of souls. There was grief that turned a man into stone. There was trauma that nearly convinced a woman the only freedom left was death. And then there was a moment, rare and fragile, when someone chose to see a person instead of property, and another person chose, against all evidence, to stay alive long enough to find out what might come next.

That, more than the scandal, more than the money, more than the gossip, was the true fate of Isabella: not that she was bought for an obscene price, but that she refused to let the world’s ugliest mathematics be the last thing that defined her.

THE END

News

Single Dad Blocked at His Own Mansion Gate — Minutes Later, He Fires the Entire Security Team

The truck coughed like it had something to confess. Caleb Reed kept both hands on the steering wheel anyway, as…

No Tutor, No Nanny Could Control the Billionaire’s Daughter — A Simple Waitress Did the Unthinkable

Manhattan liked its billionaires the way it liked its buildings: tall, polished, and unbothered by weather. Grant Wexler fit the…

The Mafia Boss Watched His Mother Get Humiliated — Until a Poor Maid Intervened

They called him the King of Quiet, the man who could make a courtroom forget its own language and a…

She Dressed Ugly for a Blind Date — Unaware He Was a Billionaire Who Fell for Her at First Sight

The coffee shop on Clark Street smelled like cinnamon syrup and burnt espresso, the kind of scent that clung to…

MY SISTER’S HUSBAND COMES FOR ME EVERY MIDNIGHT WHILE SHE WATCHES FROM HER WHEELCHAIR

“If you stop, she will die. Do you want your own sister to die?” Charles Dozier whispered the words so…

“I AM MY MOTHER’S LAWYER.” THE COURTROOM SMIRKED UNTIL A NINE-YEAR-OLD UNLOCKED THE PROOF THAT BROKE A BILLION-DOLLAR EMPIRE

CHAPTER ONE: THE MORNING THE COURT FORGOT HOW TO BREATHE The rain didn’t arrive like weather. It arrived like an…

End of content

No more pages to load