A small cabin sat a little distance away, newer than the ruins, patched with tin and prayer. On its porch an old woman sat wrapped in a quilt even though the heat still pressed its hands against the day. Her hair was white and sparse, her face lined so deeply it looked carved, and her eyes watched Lillian’s truck with no surprise at all, as though she had been expecting the sound of this engine for years.

Everett hopped down and ran to her. “Great-gran, this the lady,” he said, and then, gentler, “She just wants to listen.”

The old woman’s gaze moved to Lillian and settled, weighing. “Listening ain’t a small thing,” she said, her voice dry but steady.

Lillian introduced herself, offered her notebook, her credentials, her careful smile. The old woman did not look at the papers.

“You know what this land is?” she asked.

“I know what people say,” Lillian replied.

The old woman gave a short sound that might have been a laugh if it had carried any warmth. “People say plenty and still sleep fine. I been tryin’ to sleep for a long time.”

Lillian sat on the porch steps, lower than the woman, the way you did when you wanted to show you had not come to tower over anyone. She set the recorder between them, but did not crank it yet.

“What’s your name?” she asked softly.

The old woman’s fingers tightened on the quilt, and for a moment Lillian thought she would refuse, but then she said, “Mabel. Mabel Greene now. Weren’t always.”

Lillian nodded as if names changing were an ordinary weather event, because in the South they often were. “Everett says you hum something. Three notes.”

Mabel’s eyes flicked toward the ruins, and the cicadas seemed to quiet as if they too were leaning closer.

“That hum ain’t mine,” Mabel said. “It passed through me on its way somewhere else.”

“Where did it start?” Lillian asked.

Mabel’s mouth worked as if she were chewing something tough. “In the dark,” she said at last. “Under a house that thought it was the sky.”

Lillian waited. She had learned that silence was a door some people only opened from the inside.

Mabel’s gaze drifted toward the broken chimney, toward the vines swallowing brick. “I was born not far from here,” she said. “Back when all this stood tall and mean. I was little, little, but I remember sound. I remember it because sound was the only thing they couldn’t whip away.”

Her voice did not tremble, yet the porch seemed to shiver with it.

“You want the song,” Mabel said. “But you got to take the story, too, because the song ain’t just music. It’s a map and a warning and a hand held out in the dark.”

Lillian’s fingers curled around her pencil. “I’m listening.”

Mabel pulled the quilt higher, though the heat had not changed, and in the lowering light her face looked like it belonged to an older century. When she spoke again, it was as if the porch boards became floorboards in another house, and the air took on the damp smell of a cellar.

“In 1845,” she began, “the thunder came early that spring, and the world was already sore.”

The woman who birthed the triplets was named Ruth, though nobody with power ever wrote it down. Ruth’s name lived in the mouths of the people who loved her, and love on a plantation had to learn to be quick and quiet, the way rabbits learned to move through grass.

Ruth had hands made for work, strong and blunt-fingered, but she also had a gentleness that refused to die. When she was pregnant, the overseer stopped sending her to the far fields and kept her near the kitchen, where the work was still hard but the sun did not press straight down on her head. Women in the quarters said it was mercy; Ruth knew better. Mercy did not wear a belt with a buckle heavy enough to bruise through cloth.

On the night her labor came, the sky split open with lightning so bright it turned the cabins white for a heartbeat, and then the darkness rushed back in like water. Ruth crouched in the corner of her cabin on a blanket that had been washed so many times it had gone thin, her teeth clenched, her breath coming in sharp pulls. She had no midwife, only another enslaved woman named Ada who had learned to help because the world demanded women become their own medicine.

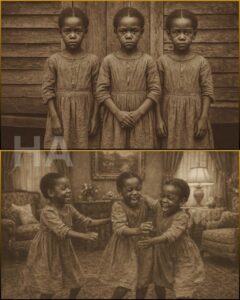

When the first baby slid into Ada’s waiting hands, Ruth sobbed once, a sound half pain and half relief, but then Ada froze, her eyes widening, because there was another head, and then another, three lives arriving like a chorus instead of a solo.

Ruth’s hands reached, shaking, and she pressed each tiny face to her cheek as if to memorize them before someone else claimed them. Her voice, hoarse with labor, poured names into their ears like seeds into soil.

“Sarah,” she whispered to the first, who blinked as if offended by light. “Cila,” she breathed to the second, whose mouth pursed like she was already holding a secret. “Serenity,” she murmured to the third, who did not cry at all but stared up at Ruth with a focus too steady for a newborn.

Ada crossed herself. “Lord,” she said.

Ruth did not look away from her daughters. “Don’t you start,” she warned gently, because superstition could be a kind of chain if you let it wrap around your mind.

But the plantation did not let miracles sit unclaimed. Boots came pounding down the dirt path before the blood had dried, and the overseer pushed into the cabin with a lantern that threw harsh light over Ruth’s body, over Ada’s hands, over the three swaddled bundles.

His name was Harlan Price, and he wore cruelty like a clean shirt.

“What’s this?” he demanded, as if Ruth had committed a theft.

Ada tried to step between him and the babies. Harlan shoved her aside, not hard enough to break bones, only enough to remind her he could.

Ruth’s arms closed tighter around her daughters. “They mine,” she said, voice low, and she knew the words were useless, but she said them anyway because sometimes a person had to speak the truth even when nobody with power cared.

Harlan’s eyes flicked over the three faces, identical as three drops of water, and something like fear flashed through him, quick and ugly, because the world he believed in depended on predictability, and triplets were not predictable. Then the fear turned into a grin.

“Master’ll want to see this,” he said.

Ruth’s stomach dropped. She opened her mouth to beg, but Ada’s hand found her wrist and squeezed once, a silent warning. Begging in front of Harlan was like bleeding in front of a dog.

They carried the babies out in rough cloth, not bothering to ask Ruth’s permission, because permission was a word enslaved people did not get to use. Ruth tried to rise, tried to follow, but pain and weakness pinned her down. She watched her daughters’ faces disappear into the night, and the sound that came out of her was not a cry so much as a torn breath, like something ripped inside her chest.

She did not sleep. She lay on the blanket staring at the cabin roof while the storm roared, and she whispered their names over and over until her tongue tasted of salt and grief.

Sarah. Cila. Serenity.

By dawn the plantation house had swallowed them.

The master of Hollow Creek was a man named Ezekiel Dunn, the sort of man who believed his name deserved carved stone. He had inherited land and bodies from his father and accepted both as naturally as he accepted weather. He did not beat people with his own hands; he employed others for that, which allowed him to think of himself as civilized.

When Harlan brought him the news, Ezekiel came to the cellar himself, lantern in hand, and stared down at the three bundles laid on straw like sacks of grain. He did not touch them. He watched them the way a gambler watched a new deck of cards, calculating odds.

“Identical,” he murmured, tasting the word. “Triplets.”

Harlan shifted uneasily. “It ain’t right,” he said, and then caught himself, because speaking of “right” in a house built on wrongness was dangerous.

Ezekiel ignored him. “Send for Dr. Mercer,” he ordered. “From Vicksburg. Pay him whatever he asks. I want this recorded.”

The cellar beneath Hollow Creek was meant for storage, for barrels of molasses and crates of silver, for things that did not breathe. It was stone-walled and damp, with a low ceiling that made tall men duck. It smelled of earth and mildew. It should not have been a nursery, but the plantation did not care what should be.

They set up a small cot, a basin, a table for papers. They stationed a house servant to bring milk and gruel, a young woman named Elinor who had been born on the plantation and had learned early that survival depended on moving quietly and looking harmless. Elinor was not allowed to speak to the babies as if they were babies. She was told to feed them, clean them, and report anything unusual.

Unusual arrived in the form of silence.

The triplets did not cry the way other infants cried, wailing for hunger or warmth or comfort. They made small sounds, breaths and soft throaty murmurs, but they did not sob. They watched. Their eyes followed Elinor’s hands as if they were studying her. When she lifted one, the other two would turn their faces in the same direction, like sunflowers tracking a sun nobody else could see.

The first time Elinor heard the humming, she thought it was the house settling, the way old wood sometimes groaned. The sound was low, steady, a vibration more than a melody, and it seemed to come from nowhere and everywhere at once. She froze at the bottom of the cellar stairs, tray in her hands, and the hairs on her arms rose.

Then she realized it was coming from the babies.

Three tiny mouths, barely capable of forming words, were humming in unison as if they had practiced. The sound was gentle, almost soothing, and still it made Elinor’s chest tighten, because it was too coordinated to be accidental.

She set the tray down and leaned closer. The babies’ eyes were open, all three staring at the same spot on the wall as if the stone held a story. Their bodies moved minutely with breath, and the hum wrapped around them like a shawl.

Elinor whispered without meaning to, “Hush, now,” the way you whispered to any child, and the triplets’ eyes flicked to her at the same time, their gaze so direct it made her feel seen through, and the humming did not stop.

Upstairs, that night, the master’s wife woke with her hand pressed to her throat, convinced she had swallowed a bee. In the quarters, men and women lay still on their pallets and listened, because the sound traveled through soil and wood, slipping into their cabins like smoke. Some covered their ears; others closed their eyes and let it hold them.

Ruth heard it, too.

She was back on her feet within days, forced to return to work before her body had finished mending, because pain was not an excuse in Ezekiel Dunn’s world. She carried pots, she scrubbed floors, she bent over laundry with her back screaming, and all the while she listened. At night, when she lay in her cabin, the humming drifted to her, and she pressed her fist against her mouth to keep from making a sound that might bring Harlan’s boots.

Her daughters were alive. Together. Unbroken.

That knowledge did not heal her, but it kept her from disappearing entirely into grief.

When Dr. James Mercer arrived, he brought the smell of city soap and medicine into the plantation’s damp air. He was a young man, not yet thirty, with dark hair slicked back and a leather satchel that clinked faintly with instruments. He had studied anatomy and called it science; he had also grown up in a world that taught him Black people were less than human, and he carried that lie in his spine the way some men carried faith.

Ezekiel greeted him with enthusiasm that was almost pride. “You will publish this,” he said. “You will note the rarity.”

Dr. Mercer smiled thinly. “Of course, Mr. Dunn.”

In the cellar he knelt beside the cot and examined the triplets with the kind of professional detachment that allowed him to pretend he was studying nature rather than stolen lives. He measured their heads with calipers, checked their eyes, their teeth, their reflexes. He wrote carefully in his ledger, ink scratching against paper.

“Remarkable,” he said, and the word sounded like a coin being weighed.

Then, as if on cue, the humming rose.

Dr. Mercer’s pen paused. He tilted his head, listening, and his brows knit together.

“Do they often… do this?” he asked Elinor, who stood by the stairs with her hands clasped.

Elinor kept her gaze lowered. “Yes, sir,” she said, because anything else would be foolish.

Dr. Mercer leaned closer, and as he did, the humming shifted slightly, the pitch sliding as though the sound were making room for his attention. He felt it in his teeth, a faint vibration, and something in his stomach tightened, a primitive unease he did not have language for.

He straightened quickly, clearing his throat. “It is likely a shared habit,” he said, more to himself than anyone. “Children mimic. Siblings influence.”

But the way the three babies’ eyes locked on him, calm and steady, made him feel for a moment like the subject rather than the observer.

That night, in the guest room, Dr. Mercer dreamed of standing in a field of cotton that reached the horizon like a white sea. He heard humming, and the sound threaded through the plants, and when he looked down he saw chains around his own ankles, heavy and rusted, and three little girls standing at the edge of the field with their hands clasped, watching him without expression. He tried to speak, to ask for help, but his mouth filled with the sound instead, the hum vibrating through his bones until he woke sweating, his heart punching against his ribs.

He told himself it was the heat. He told himself it was superstition. He told himself many things, and still, when the house fell quiet, he could hear the humming beneath the floorboards, steady as a pulse, and it made his hands shake when he tried to write.

Weeks became months. The triplets grew from infants into toddlers, then small girls with tight curls and identical faces, their bodies lean from poor food and damp air, their eyes bright with something that refused to dim. They did not speak much. Sometimes they whispered to one another in sounds Ruth could not understand when she managed to stand near the cellar door, palm pressed to the wood. The plantation called them strange. The quarters called them sacred and dangerous in the same breath.

Harlan Price tried to break them because he had never met a will he could not bend, and the triplets’ calm unsettled him more than screaming ever would have. He took his whip down into the cellar with a lantern and rage in his throat. Elinor watched from the stairs, her stomach twisting, because she could not stop him, and she had learned that looking away did not protect your soul either.

Harlan shouted. The triplets stood close together, their hands linked, their shoulders touching, and they looked at him with the steady gaze of children who had never been allowed to learn fear the normal way. When the first lash cracked, they flinched, because flesh flinches, and their mouths opened, and Elinor braced for screams.

Instead, the humming poured out, louder than she had ever heard it, three voices braiding into a sound that made the lantern flame tremble. Harlan’s arm froze mid-swing. His face changed, the grin melting away into something pale and startled. The humming rose and rose, and the air felt thick, as though the cellar had filled with unseen water.

Harlan staggered backward, dropping the whip. His mouth moved as if he were trying to form words, but nothing came out. He turned and stumbled up the stairs, shoving past Elinor without seeming to see her, and when he reached the kitchen above, he sank onto the floor and rocked like a child, his eyes wide and unfocused.

That was the first time the plantation’s cruelty showed a crack.

After that, the master’s household began to whisper about curses in the way people do when reason fails them. Ezekiel Dunn scoffed aloud, but he barred the cellar door with heavier locks and ordered Elinor never to be alone with the girls longer than it took to feed them. He told Dr. Mercer to continue his notes, but the doctor’s handwriting grew messier, as if the ink itself wanted to run away.

Ruth watched all of this from the margins, because enslaved mothers were taught to exist at the edge of their own children’s lives, and still she found ways to press love through cracks. She stole scraps of cloth and rolled them into small dolls, leaving them by the cellar door. She hummed softly at night, trying to mirror the three-note braid, trying to speak to her daughters in the only language the plantation could not confiscate.

One evening, when Ruth was sent into the house to scrub the hallway floors, she found Elinor standing near the cellar door, her face drawn and pale.

“They’re hurt,” Elinor whispered without looking at Ruth, her voice barely more than breath. “Not from today, but from always. They’re… they’re so small, Ruth.”

Ruth’s hands paused on the rag. Hearing her name spoken by someone from the big house felt like being touched through a glove. “You seen them?” Ruth asked, her throat tight.

Elinor nodded once. “I bring them food. I bring them water. That’s all they let me do, but it’s enough to see.”

Ruth’s eyes burned. “You ever talk to them?”

Elinor hesitated, then whispered, “Sometimes. I ain’t supposed to. I do anyway.”

Ruth’s voice went even lower. “Do they know my name?”

Elinor’s gaze flicked to Ruth, quick and full of something dangerous, maybe pity, maybe kinship. “They know you,” she said. “They don’t need names for that.”

Ruth pressed her palm against the cellar door, feeling the cool wood beneath her skin. For a heartbeat there was only silence. Then, from the other side, the humming rose, softer than a whisper but unmistakable, and Ruth felt it in her bones like a hand squeezing back.

Elinor swallowed hard. “They listen,” she murmured.

Ruth turned to her. “Help me,” she said, and the words came out not as a plea but as a statement of fact, because Ruth had reached the point where begging felt like dying.

Elinor’s breath caught. “If they find out…”

“They already find out whatever they want,” Ruth said, bitterness sharp as vinegar. “I ain’t askin’ you to be brave for nothin’. I’m askin’ you because you still got a choice I don’t.”

Elinor stared at the door as if she could see through it. “Where you take them?” she asked, practical even in terror.

Ruth’s mind raced along the few routes she had ever heard whispered, rivers that led away, woods that could hide a person, names like “the line” and “the North” spoken as if they were myth. “To the river,” she said. “To someone who knows the way.”

Elinor’s lips pressed together. “There’s a man,” she whispered. “Boatman. Comes sometimes, brings whiskey for the overseers. He ain’t one of us, but he ain’t one of them neither. He owes my uncle. He might…”

Ruth grabbed Elinor’s wrist, fingers desperate. “When,” she demanded.

Elinor’s voice shook. “Storm comin’ tomorrow night. Big one. They’ll all be watchin’ the sky instead of the ground. If it’s ever gonna happen, it’s then.”

Ruth nodded once. Her heart hammered like it wanted out of her chest. “Then,” she said, and she did not thank Elinor, because gratitude was too small a word for what was being offered.

That night Ruth lay on her pallet listening to the humming beneath the earth, and she whispered into the dark, “Hold on,” as though her daughters could hear the shape of her words even if they could not hear the sound.

The next day the air turned thick and metallic. Even the birds went quiet. Clouds gathered like bruises. Men in the fields squinted at the sky and muttered. Harlan Price drank early. Ezekiel Dunn paced the veranda and complained about crops as if crops were his only problem.

As dusk fell, wind pushed through the trees with restless hands. Ruth worked in the kitchen, stirring stew she would not eat, her thoughts fixed on the cellar beneath her feet. Elinor moved like a shadow, quiet, eyes down, and when she passed Ruth she brushed two fingers against Ruth’s palm, a gesture so small it could have been accidental, but Ruth felt the folded scrap of paper pressed there.

Later, when no eyes watched her, Ruth unfolded it in the dark of her cabin. Three words, written in a shaky hand: “Midnight. Back stairs.”

Ruth did not sleep. She sat with her back against the wall and listened to the storm arrive, thunder rolling like a wagon across the sky. When the plantation house lights dimmed and voices in the quarters sank into hush, Ruth slipped out of her cabin and moved through the rain.

The back stairs of the big house were slick, the wood dark with water. Ruth’s bare feet found each step by memory, because she had scrubbed them a hundred times. Inside, the house smelled of smoke and tallow and wealth. Ruth’s heart pounded so loudly she feared it would alert the walls.

Elinor waited in the hallway, a lantern shaded so its light was thin. Her face was pale in the glow.

“This is it,” Elinor whispered.

Ruth nodded.

They moved toward the cellar door. The lock was heavy, but Elinor had a key, stolen from a ring Ezekiel kept near his bed. Her hands trembled as she slid it into the metal. The click when it turned sounded like a gunshot in Ruth’s ears.

Thunder covered them.

The door opened on damp darkness, and the smell rushed up like a memory. Ruth gripped the lantern and descended the stairs, each step carrying her deeper into a place she had been forbidden to enter. Her breath came short, her palms slick.

At the bottom, the cellar stretched before her, stone walls sweating. In the far corner three small figures stood together, already awake, as though they had been waiting with their whole bodies.

Sarah. Cila. Serenity.

Ruth’s chest seized. For a moment she could not move. The girls’ faces were identical to one another and strange to Ruth at the same time, because a mother’s mind builds a child’s face through years of touch and laughter and ordinary days, and Ruth had been robbed of those. Still, she knew them. She knew their eyes, wide and steady. She knew the way they held hands as if the world might shake them apart.

The humming rose, low and urgent, and Ruth felt tears spill down her cheeks before she could stop them.

“I’m here,” she whispered, voice breaking. “I’m here, babies.”

The girls did not run to her, not like children raised with safety might have. They stepped forward slowly, their hands still linked, and when they reached Ruth they pressed their foreheads to her stomach, one after the other, as if remembering where they had once lived. Ruth sank to her knees, arms wrapping around all three at once, and in that moment the cellar did not feel like a prison. It felt like a womb turned inside out, life trying to protect itself in the only way it could.

Elinor hissed softly from the stairs. “We gotta go,” she urged.

Ruth nodded, swallowing sobs. “Can you walk?” she asked the girls.

They looked up at her. Serenity lifted her chin, almost defiant, and the humming shifted, turning into a rhythm, a pulse. The girls moved as if on that rhythm, stepping together, not stumbling, not hesitating.

Ruth’s heart clenched with fear and awe in equal measure.

They started toward the stairs, and then, above them, a shout tore through the house.

“Harlan!” someone yelled, muffled by storm.

Elinor’s eyes widened. “They’re awake,” she whispered, terror sharp.

They climbed, fast but careful, the girls between Ruth and Elinor. The hallway above was darker than it should have been, and the air smelled suddenly of smoke.

Ruth’s stomach dropped. “What’s that?” she breathed.

Elinor’s voice shook. “I don’t know.”

They moved toward the back door, and as they did, a crackle sounded, the hungry sound of wood catching fire.

Somewhere above, glass shattered. A woman screamed.

Elinor grabbed Ruth’s arm. “They gonna blame us,” she hissed. “We got to be gone before they got a mind to look down.”

Ruth’s mind raced. The fire could be accident, could be God, could be Ezekiel destroying evidence, could be Harlan drunken with rage, could be anything. In that moment it didn’t matter why, only that it was happening, a curtain of chaos falling across the house.

Outside, rain lashed the yard, but fire still ate, orange light flickering through windows. The girls’ humming rose louder, not panicked, not mournful, but steady, as if it were holding their bodies together through the storm.

They ran, Ruth’s bare feet slapping mud, Elinor’s skirt soaked and heavy, the girls moving with strange coordination as though they shared one set of lungs. Behind them men shouted, dogs barked, the plantation waking into fury.

At the edge of the yard, near the tree line, a figure waited beside a wagon half hidden under branches, a man with a wide hat pulled low. Lightning flashed, revealing his face briefly, lined and tense.

“That them?” he shouted over the storm.

Elinor nodded once. “Get us to the river,” she yelled back.

The man spat into the mud. “Climb,” he ordered.

They piled into the wagon. The man snapped the reins, and the horse lunged forward, wheels skidding in the wet earth. Ruth clutched the girls, her arms a cage made of love, and she kept her head down as the wagon bounced toward the woods.

Behind them the plantation house glowed like a wound, fire fighting rain, and through it all the humming threaded the night.

They rode hard through trees that whipped their faces, branches clawing. The horse’s breath came ragged. The wagon jolted over roots. Ruth’s muscles screamed, but she did not let go.

At the river the man pulled the wagon to a stop near a small skiff tied to a cypress knee. Water roared darkly, swollen by storm.

“Hurry,” he barked.

Elinor helped Ruth down. The girls stepped into the boat with the careful confidence of children who had grown up in darkness and learned balance there. Ruth’s heart hammered as she climbed in, the river yawning beside her like a mouth.

The man shoved them off. “I ain’t goin’,” he said, voice harsh. “I just owed a debt. You follow the bend till you see the snag that looks like a hand. There’s a man waits there. He’ll take you further. Don’t light no lantern. Don’t pray out loud. Just go.”

Elinor stared at him. “Why you doin’ this?” she demanded, as if the answer mattered.

The man’s jaw tightened. “Because I heard that hum once when I was a boy,” he snapped. “And it ain’t a sound meant to die under somebody’s floor.”

Then he shoved the boat into the current and turned away.

The river seized them.

Ruth gripped the sides of the skiff, knuckles white, as water slapped against wood. The girls sat close, their shoulders touching, and the humming poured out of them, low and unwavering, vibrating through the boat like a steady hand on a trembling spine. Elinor took the oars, her arms straining as she pulled against the current. Rain stung their faces.

On the far bank, torches bobbed, men shouting. Dogs howled. A gunshot cracked, swallowed by thunder. A bullet hit water nearby, spraying cold up into Ruth’s face.

Ruth did not scream. She could not spare breath for sound. She bent over her daughters, shielding them with her body, and in her ears the humming rose and rose, not loud enough to drown gunfire, but strong enough to keep her mind from splintering.

They rounded the bend. Trees leaned over the water. The torches fell behind. The shouting faded into storm.

Ruth’s lungs burned. Elinor’s arms shook. The girls kept humming.

When they reached the snag that looked like a hand, a second boat slid out of the reeds, guided by a man whose face Ruth could not see in the dark.

“Quick,” he whispered.

They transferred, hands grabbing hands, wet wood under palms. Ruth nearly slipped, but Serenity’s small fingers latched onto her wrist with surprising strength, anchoring her. Ruth hauled herself into the other boat, breath ragged, and the man pushed them forward into deeper darkness.

The plantation fell away behind them like a nightmare that could not swim.

They traveled nights and hid days, slipping through swamps and thickets, guided by people whose names Ruth never learned because names were dangerous currency. Sometimes they slept in barns. Sometimes under brush. Once in the crawlspace beneath a church, listening to hymns above their heads while their own bodies shook with hunger.

The girls rarely spoke. When they did, it was to one another, murmurs like birds in a nest. Their humming changed as the days passed, taking on new shapes, bending around fear, weaving in fragments of melodies Ruth recognized from the quarters, turning into something both familiar and new.

Ruth watched them with a mixture of awe and worry. She wondered what the cellar had done to them, what kind of silence it had taught their tongues. She wondered if freedom could heal what captivity had carved.

One night, weeks into their flight, they hid in a corncrib while dogs barked somewhere far away. Ruth held the girls close, her body aching with exhaustion. Elinor sat with her back against the wall, eyes fixed on a sliver of moonlight through the boards.

“I don’t know what I’m gonna be if we make it,” Elinor whispered suddenly, voice thin. “All my life I been what somebody else said.”

Ruth’s throat tightened. “You gonna be you,” she said, though she knew how hard it was to believe in a self you had never been allowed to own.

Elinor let out a shaky breath. “And you?” she asked.

Ruth looked down at her daughters. Their eyes were open, reflecting faint moonlight, and their humming filled the corncrib like a low prayer.

“I’m gonna be their mama,” Ruth said, and the simplicity of it felt like a revolution.

In the months that followed, they crossed into places where slavery still hunted them but where the net had more holes, where there were more hands willing to pull them through. They reached Memphis under cover of a freight yard, then moved north with help from people who risked their own lives for strangers because they believed God did not mean for anyone to be owned.

By the time the leaves turned, Ruth and her daughters stood on free soil in Ohio, shivering in cold they had never known. Elinor stood beside them, her hands cracked, her eyes hollow with fatigue and bright with disbelief.

A woman in a wool coat led them into a small house and set bread on the table. Ruth stared at it as if it might vanish. When her fingers finally touched it, she began to weep, not loudly, not dramatically, but with the quiet overflow of someone whose body had been a dam too long.

The triplets did not cry. They climbed onto Ruth’s lap, all three at once, and their humming softened into something almost like a lullaby. Ruth rocked them, and for the first time in their lives no one opened a door to take them away.

Years passed. The Civil War came like a firestorm across the nation, burning away legal chains while leaving other chains stubbornly intact. Ruth worked as a laundress, then as a cook. Elinor learned to read. The triplets grew into young women with identical faces and distinct spirits, their voices strong and clear.

Sarah had a laugh that startled birds. Cila had a habit of watching people’s hands the way she used to watch Elinor’s in the cellar, as if hands told truer stories than mouths. Serenity spoke the least, but when she did, her words carried weight like river stones.

They sang, not just humming now, but singing, and the three-note braid that had haunted Hollow Creek became the spine of their music. They sang in churches. They sang at abolition meetings. They sang at funerals for men who never made it north. Their sound was not unholy. It was holy in the way survival is holy, in the way a name spoken aloud after years of silence is holy.

Ruth lived long enough to see her daughters choose their own lives, to see them marry or not marry as they wished, to see them hold their own children without fear of boots at the door. She died with their hands in hers, the three of them humming softly as her breath slipped away, and if her spirit carried anything with it, it carried their names, finally safe to be spoken in daylight.

Back in 1937, on the porch beside the ruins, Mabel’s voice faltered as she reached that part, and she stared hard at her quilt as if it contained the shape of old pain.

“They didn’t die,” she said, almost fierce. “They got out.”

Lillian’s pencil had stopped moving. Her eyes burned. The recorder’s little wheel turned steadily, catching each syllable, as if the machine itself understood the importance of not letting this vanish again.

“How do you know?” Lillian asked carefully.

Mabel lifted her gaze. “Because my mama’s mama went north later,” she said. “After the war. She found folks. She found the song. She told me the truth when she thought I was old enough to carry it without droppin’ it.”

Everett shifted on the porch, eyes wide. “Great-gran, you never told me,” he whispered.

Mabel reached out and squeezed his hand, her fingers papery but firm. “Some stories you don’t give a child till you know he can keep it from breakin’ him,” she said.

Lillian swallowed. “What happened to Hollow Creek?” she asked, though the ruins offered one answer already.

Mabel’s mouth tightened. “They rebuilt some, tried to,” she said. “But the land got tired of holdin’ their lies. Folks said they heard hummin’ in the floors, and they left. Place fell apart. But the song didn’t.”

Lillian nodded slowly, her mind running ahead, imagining archives, church records, gravestones, names that might have been written down in Ohio. She felt the itch of a historian and the ache of a daughter at the same time.

“Will you hum it?” she asked gently. “Just the three notes. So I can write it true.”

Mabel’s eyes closed. For a heartbeat the porch held its breath.

Then Mabel’s throat released a low sound, steady and sure, three notes braided so tightly they did not feel separate. It was the sound Lillian had been hearing all summer, but here, on this porch beside the bones of Hollow Creek, it felt like standing at the mouth of a river and finally seeing where the water came from.

Everett’s lips parted, and without thinking, he joined her, matching the tone as if his blood remembered the path. Lillian felt tears slide down her cheeks, and she did not wipe them away.

When Mabel finished, the cicadas resumed their argument, and the night air moved again, but something had shifted in Lillian’s chest, a knot loosening.

“I want to find them,” Lillian said, voice rough. “Their graves, their records, anything with their names.”

Mabel looked at her, and for the first time something like softness flickered across her face. “Names matter,” she said. “That’s the whole point.”

The next day Lillian walked through the ruins with Everett trailing behind her, careful of snakes and broken brick. She found the cellar entrance half-collapsed, vines creeping over stone. She crouched and pressed her palm against the cool wall. It did not hum. Not in any way she could hear. Still, she felt the weight of what had been held there, what had been endured, what had been carried out into storm.

She took out her pocketknife and carved three small marks into a standing stone near the entrance, not as a secret this time, but as a beginning.

Everett watched, solemn. “That for them?” he asked.

“For them,” Lillian said, “and for everybody they tried to erase.”

Before she left, Mabel handed her a scrap of paper, brittle with age, folded so many times it held creases like scars. On it were three names written carefully in a wavering hand, and beneath them, a place: “Oberlin.”

Lillian held the paper as if it were a living thing.

In October she traveled north, following the map hidden inside a hum. In Oberlin she found church ledgers that listed Ruth by name, finally, not as property but as a member. She found marriage records for Sarah. She found a cemetery with three stones side by side, weathered but readable, and on them the names that had once been whispered into newborn ears in a storm-lit cabin.

Sarah Freeman.

Cila Freeman.

Serenity Freeman.

The surname hit Lillian like a bell. Not Dunn’s. Not Price’s. Not anyone’s but their own chosen truth.

She stood there in the cold and hummed the three notes, letting them curl into the air above the graves like a soft ribbon, and she imagined Ruth somewhere beyond sight hearing it and knowing, finally, that the world had spoken her daughters’ names without fear.

When Lillian returned to Mississippi the following spring, she brought a small box of cedar saplings, three of them, and she planted them near the ruins where the cellar once held children like secrets. Everett helped her dig. Mabel watched from the porch, her eyes bright and wet.

“Trees,” Mabel murmured, “for girls they tried to bury.”

“For women,” Lillian corrected softly, because names were not the only things time stole.

The saplings stood thin and hopeful in the soil. The wind moved through them, and for a moment, just a moment, Lillian thought she felt the faintest vibration under her feet, not a haunting exactly, but a memory settling into place, the way a weary body finally finds a bed.

When she packed her notebook and recorder into the truck, Mabel called after her, voice firm.

“Write it right,” she said. “Don’t make ‘em monsters. Don’t make ‘em magic to scare folks. They was children. They was daughters. They was brave, and they was loved, and they lived.”

Lillian turned, meeting the old woman’s gaze, and nodded. “I will,” she promised, and this time the promise felt like something solid.

As she drove away, the road unwound through trees and fields, through a land that had tried to swallow its own sins, and in the cab of the truck the three-note hum lingered, not as a ghost, but as proof.

Proof that a story could be burned and still survive in mouths.

Proof that a name could be stolen and still return.

Proof that even when the world built a cellar for you, you could still learn the sound of the door opening, and you could walk out together, hands clasped, into the storm, carrying a song the masters could never own.

News

Given to a Duke Far Too Old, She Wept for Her Dreams—But on Wedding Night His First Gift Amazed Her

For a long time, he said nothing. Isolde told herself she preferred it. Then, as the carriage turned onto a…

She Married a Poor Mountain Man but he drove her to His Secret Hidden Mansion

Mara stayed by the table, her needle paused mid-stitch, watching him the way you watched a stranger near a cliff…

“I Am Not Fit for Any Man, The Curvy Woman Said —But I Can Love Your Children.” The Cowboy Went Quiet

That night, she sent a telegram from the post office and bought a train ticket with almost all the money…

The Master’s Twisted Experiment: Pairing His ‘Unfit’ Son with the Strongest Enslaved Woman

Eleanor did not live long enough to see what her insistence had bought. Yellow fever came through the county in…

63 Year Old Melissa Sue Anderson Finally ADMITS What Michael Landon Did Behind The Scenes

Melissa looked at the producer, and in his face she saw the audience he represented: people hungry for revelation, for…

The Incredible Mystery of the Oldest Slave to Ever Live—No One Knew How ……

Nathaniel tried to smile like that warning was just superstition. “Is she dangerous?” The clerk didn’t smile back. “Danger ain’t…

End of content

No more pages to load