The mountains in the Pacific Northwest have a way of swallowing sound, especially where the cedar stands thicken into a living wall and the daylight turns timid. In 1903, the hamlet of Hawthorne Ridge, Washington, counted fewer than four hundred people who survived by felling timber, curing meat, and pretending winter wasn’t personal. It was the sort of place where the road gave up before the forest did, and where a secret could sit for years, heavy as a stone in a pocket, never quite pulling you under until the moment you stopped fighting it. Fifteen miles beyond the last general store, past a switchback trail locals took only when desperate, stood the Hart property, a two story house built from the same trees that bled into its foundation. Everyone called it “the Hart place,” but no one said it warmly, because names were safer when they stayed flat.

Gideon Hart had purchased that land in 1886 with a young man’s belief that hard work could out-muscle fate. He built a sawmill beside a creek that ran cold even in July, and he raised walls that smelled of fresh sap, as if the house itself were still alive. In 1887, his wife Eleanor died in childbirth, leaving him with twins, a boy and a girl, and the kind of grief that makes a person move carefully around their own thoughts. Gideon grew respectable in town, but he never grew social; he spoke with his hands more than his mouth, and he prayed as if God were a foreman who might notice his effort. The twins were named Mara and Miles, and from the beginning they carried a stillness that unsettled people, as if they were listening to a song no one else could hear.

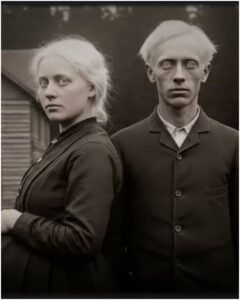

Mara and Miles grew up pale as birch bark, their hair so light it looked almost silver under lamplight, their eyes a sharp, winter blue. Gideon tried to bring them to church, to picnics, to the small rituals of community that might teach them the shapes of ordinary life, but the twins clung to each other with a gravity that rejected extra bodies. If someone asked Mara a question, Miles answered before her lips parted; if Miles stumbled, Mara steadied him without looking, like she’d received the signal through the air. Gideon told himself it was close sibling affection sharpened by loss, and he said it with enough conviction to quiet his own unease. Yet every time the twins turned toward one another in perfect sync, Gideon felt a small, cold tap in his chest, a warning that refused to become words.

The warning gained teeth the day Hawthorne Ridge reminded the twins they were different. In 1896, when Mara was eleven, Gideon brought the children into town for supplies and school papers, hoping the public world would rub off on them like sunlight. A group of older kids circled Mara behind the mercantile, mimicking her quiet voice and calling her “ghost girl” while she stared at her shoes as if the ground might open and make her safe. Gideon arrived too late to stop the first cruelty, but not too late to see it, and the sight set something rigid in him. He marched the twins home, and in the weeks that followed, his trips into town became rarer, his conversations shorter, his trust thinner. Gideon didn’t announce his decision like a decree; he simply withdrew, and the forest, delighted, closed its fingers around them.

Isolation, at first, felt like protection. The sawmill gave Gideon purpose, and the woods gave the twins a world that asked nothing of them except silence. But the older the twins grew, the more their shared language sharpened into a blade Gideon couldn’t grip. By the time they turned eighteen in 1902, Mara and Miles spent hours in the attic with the door locked, and when Gideon called them down for supper, their footsteps arrived together, their faces arranged in the same calm mask. Gideon began to notice long stretches of quiet between them that didn’t feel empty; it felt crowded, as if whole conversations were happening in the space between their eyes. He tried to ask gentle questions, and the twins answered politely, but their answers never landed, like they were offering him coins from a currency he couldn’t spend.

That winter, Gideon discovered the attic wasn’t just a hiding place. It was a library. The twins had found trunks of books left by Gideon’s father, a man the town remembered as “odd,” meaning he asked questions that made people uncomfortable. There were genealogies, old family line charts, texts on animal breeding and heredity, and brittle pamphlets about “improving stock” that treated life as if it were lumber you could plane into perfection. Gideon didn’t understand most of it, and the parts he did understand made him feel sick in a quiet way, the kind of sickness that starts as a thought and ends as a tremor. When he confronted the twins about the books, Mara smiled faintly and said, “We’re just learning.” Miles added, almost tenderly, “You taught us to build. We’re building, too.”

The snow came early in 1902 and stayed long past its welcome. For three months the Hart place was cut off, the road swallowed by drifts, the creek locked under ice, the world reduced to wood smoke and footsteps on frozen boards. Gideon expected cabin fever, arguments, the rough edges of people forced too close, but Mara and Miles grew only calmer, as if the storm had given them permission to become exactly what they wanted. They moved through the house with quiet purpose, sharing looks, touching wrists, turning away from Gideon as if he were furniture. Gideon drank more than he admitted to himself, not because he liked the taste, but because the burn in his throat gave him something simple to focus on. By the time spring broke the road open again, Gideon was hungry for town noise, for human voices that didn’t belong to his children.

When he went down to Hawthorne Ridge for supplies, the merchant mentioned, smiling, that Gideon must be proud about the wedding. The word struck Gideon like a mis-aimed tool, surprising and sharp. He asked what wedding, and the merchant, suddenly awkward, explained that Miss Mara had been in weeks earlier buying white fabric and ribbon, speaking of a “family ceremony.” Gideon’s confusion collapsed into dread on the ride home, and every hoofbeat sounded like a countdown. He arrived to find the house oddly neat, the parlor cleared as if for guests that would never come. Mara and Miles sat side by side, hands folded, their posture so composed it felt rehearsed, and Gideon realized with a sinking certainty that whatever they were about to say had already been decided.

They told him without flinching. Mara spoke first, her voice soft but steady, saying she and Miles had chosen to marry, and Miles finished the sentence, explaining it wasn’t an impulse but a conclusion. They referenced the old books upstairs, the “pure line” arguments, the historic families who “kept what was special” by folding blood back into itself. Gideon’s anger arrived loud, laced with scripture, with law, with the desperate insistence that some boundaries exist for a reason. The twins listened with the calm of people watching weather pass, and when Gideon threatened to throw them out, Miles reminded him, gently, that they were adults, legal heirs, and that on isolated land, “many things are only as real as the people who witness them.” Gideon realized then that he was not the father in control of a household; he was a lone man in a house that had quietly chosen new owners.

The ceremony happened on a May morning in 1903 behind the house, where the grass had been pressed flat as if it expected feet. There was no pastor, no congregation, no music, only birds that refused to come close and the steady creak of trees shifting in wind. Mara wore the white fabric she’d bought in town, wrapped and pinned into a dress that looked too pure for what it represented. Miles wore his best shirt and held a small notebook, and Gideon, trembling with shame, was forced into the role of witness because the twins insisted “a family must see itself.” They spoke vows they’d written together, words about unity and destiny and “keeping what is ours,” and when they kissed, Gideon turned away, feeling the forest stare through him. That night, he locked his bedroom door, not because a lock could save him, but because it allowed him to pretend he was still allowed to draw lines.

Afterward, the house changed, and not in ways Gideon could easily name. Doors gained extra latches. Certain windows were boarded. The attic became more private, and the basement, once just cold storage and tools, began to echo with work at night. Mara and Miles made purchases in town that didn’t match any ordinary kind of nesting: sacks of lime, heavy rope, nails by the pound, nonperishable food stacked in quantities meant for siege. When Gideon asked what they were preparing for, Mara replied, “For our family,” as if that was a weather forecast rather than a threat. Gideon tried to hold on to the sawmill as a refuge, but even there, among the honest noise of blades and timber, he felt the house waiting for him, patient as rot.

By autumn, Mara was pregnant. The news should have softened Gideon, should have pushed him toward hope, but it landed like a stone in his gut, because he could not separate the idea of a child from the way that child had been made. Mara and Miles reacted to the pregnancy with a composed excitement that looked more like planning than joy. They whispered together constantly, scribbling in a notebook Gideon never saw open long enough to read. When labor came on a storm-heavy night in March 1904, Gideon woke to Mara’s cries, raw and human, and for a moment he believed the spell might break. Then Miles blocked the doorway, calm as a priest, and said, “This is ours,” and Gideon, frozen between rage and fear, obeyed the boundary like it was law.

When he finally saw the baby, a girl, Gideon’s heart twisted. The child’s body showed visible differences that made Gideon’s breath catch, and he felt grief arrive before love could find a place to stand. Yet Mara and Miles looked at their daughter with a fascinated satisfaction, as if the child had confirmed a hypothesis rather than become a person. Mara murmured that the baby was “exactly as expected,” and Miles smiled in a way that didn’t reach his eyes. Gideon tried to ask about a doctor, about care, about the simple mercy of treating a child as a child, but the twins answered in cool fragments, assuring him they had it “controlled.” The baby was kept mostly out of sight, and Gideon found himself hearing small sounds through walls, then doubting his own ears the moment he tried to follow them.

A second pregnancy came quickly, and Gideon’s dread did not have time to rest. By then, the basement door was always locked, and the twins moved in and out with buckets and bundles at odd hours. Gideon began to hear crying from below some nights, a thin sound that threaded into his dreams and turned them violent. When he mentioned it, Mara said it was the wind in old boards, and Miles added, pleasantly, that Gideon was drinking too much, that alcohol could make a man imagine things. Gideon hated them for that, not because it was cruel, but because it was plausible, and he felt the shame of doubt weakening him. When the second child, a boy, was born during a blizzard in December 1904, Gideon saw him only briefly, and the baby appeared physically typical, pink and strong. The twins’ reaction, however, was not relief but disappointment, as if the child had arrived with the wrong answer.

That was when Gideon first saw the twins’ love turn selective, and it chilled him more than any winter. The first child, the girl with visible differences, received meticulous attention and constant monitoring. The second, the “ordinary” boy, was left alone for long stretches, his cries muffled by doors Gideon wasn’t allowed to open. Gideon tried to intervene, but every attempt ended the same way: a calm stare from Mara, a measured step from Miles, and a reminder that Gideon was “tired,” “confused,” “in the way.” Gideon, a man who’d wrestled trees into planks, found himself powerless against the quiet certainty of two people who had decided empathy was a variable they didn’t need.

In early 1905, an experienced hunter named Silas Crowe noticed something odd on his routes through the mountains. Smoke rising from the Hart chimney at hours when no one should be awake, lights moving behind boarded windows, a stillness around the property that felt cultivated. Silas was not a gossip and not a coward, and his curiosity had teeth, sharpened by years of reading the land like a book. When he finally approached the Hart place under the excuse of checking in on an old acquaintance, Mara and Miles received him with coffee and polite conversation. Silas noted what wasn’t present as much as what was: no children’s laughter, no baby cries, no evidence of a growing family except the locks and the smell of disinfectant. The twins spoke in synchronized rhythms, finishing each other’s ideas, and Silas left with a hard knot in his stomach that only tightened as he walked away.

Silas asked questions in town, careful not to sound dramatic. He learned that few people had seen the Hart children, that the local doctor grew evasive whenever the family was mentioned, that the twins bought supplies in odd quantities and paid in cash as if they feared records. That suspicion, once formed, became a moral itch Silas could not ignore. He began observing the property from a distance, using the forest’s own patience against it, and he saw patterns that didn’t belong to ordinary life: nighttime trips to the basement, burying of waste far from the house, and brief, shadowy movements in the yard like someone being guided rather than walking freely. Silas told himself he might be wrong, because wrongness was easier to live with than the alternative. But on a dawn in late February 1905, he crept close and peered through an uncovered sliver of basement window, and what he saw emptied his lungs.

The basement had been divided into small spaces with reinforced doors and narrow vents, like pens made for something that could suffer. Silas saw Mara and Miles moving between those spaces with bowls and buckets, calm as caretakers, and he heard the unmistakable sounds of children, not playing, not speaking, but making the small, broken noises of bodies trying to exist inside limits. Silas stumbled backward, his mind refusing to accept what his eyes had already recorded, and for a moment the forest seemed to tilt. He turned to leave and found Miles in the doorway, as if the house had warned him. There was no shouted confrontation, no dramatic struggle that a story would later simplify into hero and villain. There was only the quiet inevitability of a trap closing, and Silas Crowe did not come home from that mountain.

His absence disturbed Hawthorne Ridge in a way that felt superstitious at first and practical later. Search parties found his rifle in the woods a mile from the Hart place, but they found no blood, no tracks that made sense, no body. Mara and Miles acted surprised and concerned when questioned, offering assistance, speaking kindly, and their performance was so smooth it made people feel foolish for suspecting them. Gideon, watching from the edges of these exchanges, felt his own fear calcify into something like certainty. If the twins could erase a grown man without leaving the kind of mess the forest usually insists upon, then Gideon understood what they could do to someone trapped under their roof. The house, once a symbol of Gideon’s ambition, became his cage, and every night he listened for sounds below, praying for silence because the alternative was unbearable.

Years passed with the slow cruelty of routine. Children existed in the Hart place, more than town records admitted, and the twins treated each new life like a chapter in a private study. Gideon’s health thinned, his hands shaking at the sawmill, his appetite evaporating into dread. He began marking days on a beam in the attic, a childlike attempt to keep time from dissolving completely. He tried, more than once, to confront Mara and Miles with the force of a father reclaiming a household, but each attempt ended with the same cold solution: the twins speaking softly about Gideon’s “weak heart,” about the danger of “interference,” about how easy it would be for town to believe an older man had wandered into the woods and never returned. Gideon learned to swallow his courage like a bitter medicine, and it poisoned him slowly.

In December 1912, Dr. Miriam Kline, newly arrived from a larger town and less conditioned to local silence, noticed discrepancies in birth records and whispered rumors. She had heard Silas Crowe’s name in a conversation that paused too hard, and she recognized the shape of communal fear, how it gathers like fog around a single place. Dr. Kline tried to approach the matter carefully, requesting a medical visit under the polite language of concern, but concern can be a spotlight, and spotlights provoke shadows. She traveled toward the Hart property and did not return. Her carriage was found abandoned on the road, horses trembling, medical bag spilled open as if she had dropped it while running. The town’s fear turned from rumor into proof, and proof, at last, forced the sheriff’s hand.

Sheriff Nolan Pierce avoided the Hart place for years because avoidance is the oldest policy in small towns. But by March 1913, pressure came from outside, from families who asked about missing travelers and from officials who disliked unanswered questions. Pierce obtained a warrant on suspicion tied to multiple disappearances, and on a foggy morning he rode to the Hart property with two deputies and a county representative. The house looked older than it should have, as if dread had aged the wood faster than weather. The silence around it was unnatural, a pocket where birds refused to sing, and Pierce felt, briefly, like a man approaching a church that had forgotten what mercy meant. Mara and Miles met them on the porch with identical smiles and the calm of people who had rehearsed this day for years.

Inside, the house revealed itself as a machine built for control. Doors reinforced with metal, windows sealed, locks on rooms that should have held nothing but linen and dust. Upstairs, Pierce found nurseries with no warmth, and walls covered with diagrams and family trees drawn like maps of obsession. There were notebooks filled with clinical observations of children identified by numbers and traits, not names, as if personhood was an inconvenience. Pierce felt his stomach turn, but he kept moving because stopping would mean giving the horror time to become personal. In a small upstairs room with poor ventilation, they found a child, a girl around nine, frightened and thin, her body showing the consequences of years without proper care. When the deputies tried to help, the girl shrank from touch and made sharp, unfamiliar cries, not because she was animal, but because she had been treated as less than human long enough for language to fail.

The basement was worse, not because it was filled with monsters, but because it was filled with what monsters leave behind. Reinforced compartments lined the walls, each with small vents and a narrow opening like a feeding slot. In one, Pierce found a boy around eight who stared through people rather than at them, his mind trained into a survival loop of repetitive movements. In another, a girl around seven who hid from light as if brightness were punishment, her skin showing wounds that spoke of restraint and neglect. A third compartment stood empty but stank of recent suffering, and scratch marks scored the wall in frantic tallies. In the farthest corner, partially covered, they found the remains of a small child, and the sight silenced even the deputy who swore for a living. Pierce confronted Mara and Miles, expecting denial, rage, anything that belonged to ordinary guilt, but Miles only said, calmly, that “not all subjects survive,” and Mara added that “observation requires sacrifice,” as if they were discussing weathered wood.

In a locked attic room, they found Gideon Hart, barely recognizable as the man who once commanded a sawmill. He was malnourished, eyes darting, whispering about “the rooms below” and “the counting” and “the ones who shouldn’t exist.” When Pierce freed him, Gideon clutched the sheriff’s sleeve with desperate strength and tried to speak, but his words fell apart, not from stupidity, but from years of carrying terror alone. Pierce understood, then, that Gideon had not been an accomplice so much as a captive who survived by shrinking. The deputies carried children out into the gray morning, and the children reacted to open air with fear, not relief, because freedom is frightening when you’ve been trained to expect pain. The town watched from a distance later, horrified, and realized their silence had been part of the structure, another lock on another door.

The trial in late 1913 drew crowds from neighboring counties, because people treat horror like a fire, gathering close enough to feel heat but hoping not to be burned. Prosecutors laid out notebooks, diagrams, evidence of lures and traps, and the records of disappearances. Mara and Miles listened as if attending a lecture, never quite recognizing themselves in the language of crime. Experts argued about isolation, about shared delusion, about how a mind can become its own sealed room, but the planning was too deliberate, the system too precise, to pretend it was confusion alone. The verdict came unanimous: guilty on multiple charges, including murder and aggravated abuse. When the judge sentenced them to life, Mara and Miles showed no collapse, no tears, only a quiet, identical stillness that suggested they believed time would prove them right. The courtroom’s relief felt thin, because everyone sensed the true sentence belonged not only to the twins, but to the children who would carry the consequences forever.

Recovery was not a clean arc, because real life rarely respects the shape of a story. The children were placed in specialized care, and doctors documented improvements that felt small but mattered: a word learned, a hand unclenched, a flinch that softened into a hesitant glance. The oldest girl never walked easily, her body shaped by years of confinement, but she learned to sit by a window and watch sunlight without panicking, which in that context was a kind of victory. The boy with the vacant stare learned a few simple phrases and, more importantly, learned that some footsteps did not mean punishment. One of the younger children, already too damaged physically, died within a few years, and the town mourned with the raw shame of people who realized grief can be compounded by guilt. The last surviving child reached adolescence with deep fears that never fully loosened, but found a steady caretaker who treated him as a person, not a problem, and that steadiness mattered more than any miracle.

Gideon Hart never returned to the sawmill. He spent his remaining years in a state facility where staff spoke gently and kept the lights soft, and sometimes he would grip a pencil and draw crude lines, still counting days, still trying to prove to himself he had not imagined the sounds. He died before the decade ended, his prayers unfinished, his fatherhood stained by forces that had moved through his home like smoke. The Hart property was abandoned and later burned in 1919, whether by lightning or by human hands that wanted cleansing. People said the fire was merciful, because it erased the structure, but the land remained, and the trees kept growing, indifferent and ancient. The mountains did not whisper the truth out loud, yet the town changed in subtle ways: neighbors began checking on neighbors, and silence stopped being mistaken for politeness.

If Hawthorne Ridge learned anything, it was not the easy lesson that evil looks obvious. It was the harder lesson that evil often looks like routine: a locked door explained away, a missing person turned into a shrug, a crying sound blamed on wind because wind is easier than responsibility. Mara and Miles Hart did not act in explosive rage or sudden madness; they acted in calm, ordered steps, and that was what made them frightening. Their obsession wore the costume of logic, and they used that costume to strip personhood from their own children. In the end, the sheriff’s lantern did what sunlight often fails to do in dense forest: it cut a path through shadows long enough for others to follow. And the children, even those who did not live long, proved something the twins never understood: a human being is not a specimen, not a variable, not a note in a ledger, but a life that deserves care simply because it exists.

THE END

News

All Doctors Gave Up… Billionaire Declared DEAD—Until Poor Maid’s Toddler Slept On Him Overnight

The private wing of St. Gabriel Medical Center had its own kind of silence, the expensive kind, padded and perfumed…

Mafia Boss Arrived Home Unannounced And Saw The Maid With His Triplets — What He Saw Froze Him

Vincent Moretti didn’t announce his return because men like him never did. In his world, surprises kept you breathing. Schedules…

Poor Waitress Shielded An Old Man From Gunmen – Next Day, Mafia Boss Sends 4 Guards To Her Cafe

The gun hovered so close to her chest that she could see the tiny scratch on the barrel, the place…

Her Therapist Calls The Mafia Boss — She Didn’t Trip Someone Smashed Her Ankle

Clara Wynn pressed her palm to the corridor’s paneled wall, not because she needed the support, but because she needed…

Unaware Her Father Was A Secret Trillionaire Who Bought His Company, Husband Signs Divorce Papers On

The divorce papers landed on the blanket like an insult dressed in linen. Not tossed, not dropped, not even hurried,…

She Got in the Wrong Car on Christmas Eve, Mafia Boss Locked the Doors and said ‘You’re Not Leaving”

Emma Hart got into the wrong car at 11:47 p.m. on Christmas Eve with a dead phone, a discount dress,…

End of content

No more pages to load