In the low, wet country outside Charleston, South Carolina, people liked their explanations tidy. When a child’s fever turned strange, when a plantation overseer vanished along a narrow levee road, when a healthy man woke up shaking as if winter had crawled into his bones, the doctors in town would lift their hands and say what everyone wanted to hear: The swamp takes what it wants, and it always wants more. It sounded like wisdom, the kind that let you sleep at night. It was also a velvet curtain, pulled over things too ugly to name out loud.

Thorne Manor sat twenty miles from the city, and the land around it looked like it had been poured from a bottle of ink. Rice fields lay in obedient squares, their flooded mirrors reflecting a sky that never seemed fully clean. Indigo grew in dark rows like bruises on the earth. Along the drive, the willows did not sway so much as hang, their branches drooping like mourners who had forgotten how to stand. Even the air carried two perfumes at once, jasmine and rot, sweetness braided with decay, and the braid tightened in your throat if you stayed too long. The big house had once been proud in the Georgian style, white columns and a wide front porch meant for laughter and lemonade. Now the paint peeled in curled sheets, the clapboards swallowed moisture, and the windows stared out with the dull patience of a man listening for footsteps that never came.

Inside, the only constant music came from a small wooden box in the eastern wing, a music box that played the memory of a lullaby more than the lullaby itself. Its little metal teeth were bent, and its melody limped, one note always arriving late like a guest who had missed the point of the party. Servants kept their eyes down when it chimed. The overseers pretended they didn’t hear it. Governor Alistair Thorne, who owned the manor, the fields, the mill, and every life tethered to them, would pause once in a while as if listening, then resume his stride with the irritability of a man being mocked by a thing too small to punish. Only his daughter, Aurelia Thorne, seemed to welcome the broken tune. It was hers, in the way lonely people claim objects: not because it belonged, but because it understood.

Aurelia was twenty-one and already spoken of in Charleston parlors with the careful cruelty reserved for women who don’t fit the narrow doors society builds for them. She was large, pale, and undeniably striking in a way that made people uncomfortable, as if beauty had wandered into the wrong room and refused to apologize. Her eyes were the color of a storm over the harbor, slate and restless, and her mouth looked perpetually poised to pass judgment. She moved with deliberate grace, as though she’d learned early that the world would take her body as an argument against her and she’d decided to answer with control. Her father called her “formidable” when he wanted to sound charitable, “a burden” when he didn’t care who heard. When he looked at her, he did so the way one might look at a ledger entry that refuses to balance.

Her mother had been a foreign woman with an accent that never softened into Carolina vowels, a woman the governor had married for reasons nobody in Charleston could quite untangle. She died when Aurelia was young, leaving behind trunks of books written in languages the household staff swore could not be spoken without inviting illness. Alongside the books were sketches of anatomy, pressed herbs, jars of insects pinned like punctuation, and a thin, silver charm engraved with symbols that looked like letters and claws at the same time. The governor locked the trunks away at first, then grew tired of fighting with a child who cried quietly but stubbornly until she was given what she wanted. So the eastern wing became Aurelia’s kingdom, a gilded cage with a view of black water and reeds that hissed when the wind passed through. If visitors asked after his daughter, Alistair would say, “She prefers her studies,”

and the way he said it suggested “studies” were a disease.

In her rooms, Aurelia built something between a library and a laboratory. Books lined the walls, leather-bound volumes with titles in Latin and French, and stranger scripts that seemed to twist when you didn’t look directly at them. There were diagrams of the human throat, the inner ear, the delicate branching of nerves in the hand. On her writing desk, ink stained the wood like old blood, and the smell of dried nightshade hung in the air, floral and threatening. She kept a mortar and pestle beside her candle, and sometimes, late at night, the servants would see the glow of her window and whisper that she was talking to the dead. In truth, she mostly talked to paper. Paper did not flinch. Paper did not laugh. Paper listened.

If Aurelia’s education was the only thing in her life that felt like choice, her birthday reminded her how little choice she truly had. The dinner for her twenty-first year was held in the formal dining room, a wide space where the table looked long enough to be a river. Candles trembled in their holders, fighting shadows that clung to the tapestries like damp. The governor ate with the precision of a man who believed every gesture should be a lesson. He did not say “Happy birthday.” He did not ask what she was reading. He spoke instead of losses in the fields, of the rice crop, of mosquitoes, of doctors who charged too much and accomplished too little. Every complaint landed like a pebble tossed at her, small but meant to sting.

At last, when the silverware had made enough noise to fill the silence, he set down his knife and looked at her as if she were a problem he meant to solve by force. “A proposal has been arranged,” he said, voice smooth as polished wood. “Baron Hargrove. Widower. He is… practical. He will accept you.”

Aurelia’s fingers stopped mid-motion above her plate. “Accept,” she repeated, tasting the word as if it might be poisoned.

“He needs an heir. You need a household,” Alistair replied. “And I need to stop fielding questions about why my only child has become a rumor.”

“And if I refuse?” Aurelia asked softly.

Her father smiled without warmth. “Then you will remain here, a curiosity with no future. And curiosities tend to rot when left unattended.”

The governor stood, signaling the dinner’s end with the same casual authority he used to signal a man’s punishment. “Come,” he said. “Your gift is waiting.”

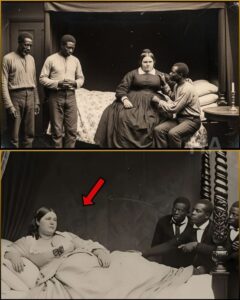

The courtyard was lit by torches that made the mud shine. Three men knelt in it, their wrists chained, their shirts damp with sweat despite the evening breeze. The governor’s overseer stood behind them with a whip looped over one shoulder like an accessory. Aurelia paused at the top of the steps, her skirts catching a gust of air that smelled of brine and distant rain. She took in the scene the way she took in her mother’s diagrams: thoroughly, with a scholar’s attention and a predator’s calm.

“Purchased today,” Alistair announced, as if he were presenting horses. “Strong stock. Yours, Aurelia. If you insist on remaining unmarried, you will at least learn what it is to manage property.”

Aurelia’s pulse thudded once behind her eyes. She felt the humiliation of it, public and sharp, meant for any servant peeking through windows and any overseer lingering too close. Look, the gift said. This is what you are, daughter of mine. A mistress without a husband, a woman made ridiculous, handed men like tools so you can pretend you hold power.

The men raised their faces. The first, Kale, had a jaw set like stone and eyes that refused to lower. The second, Ree, was younger, with hands that looked as if they’d once learned music, fingers long and scarred in a way that suggested careful work turned brutal by necessity. The third, Celas, held himself quietly, attentive as a man who had learned that surviving often meant becoming invisible. Aurelia noticed details she should not have been able to notice in a heartbeat, the old bruise on Kale’s cheekbone, the fresh split on Ree’s lip, the way Celas’s gaze flicked to the shadows as if measuring routes.

“Stand,” she said, and her voice surprised even her by how steady it sounded.

The overseer moved, tugging chains, but Aurelia lifted a hand. “No,” she said. “Let them stand on their own. Or is that too much to ask of your management?”

The overseer hesitated, glancing at the governor. Alistair gave a small nod, amused, as if indulging a child playing at authority. The men rose slowly, joints stiff from kneeling, and the chains clinked like a quiet warning. Aurelia descended the steps, stopping just close enough to smell them, sweat and swamp air and something metallic that suggested blood had been near recently.

“What are your names?” she asked.

The overseer began to speak, but Aurelia’s eyes snapped to him. “Not you,” she said. “Them.”

Kale’s stare did not waver. “Kale,” he said.

“Ree,” the younger one answered.

Celas waited half a breath, then said, “Celas, ma’am,” with the careful politeness of a man walking on thin ice.

Aurelia looked at her father. “You’ve given me men,” she said, “as if I were a lonely widow buying comfort. But what you truly give me is a lesson in cruelty.”

Alistair’s eyebrows lifted. “And you will learn it quickly,” he replied. “Because the world will not grant you gentleness.”

Aurelia turned back to the three men, and for a moment her expression softened into something unreadable. Then she said, “You are mine, then. And if I am a lesson, you will be one too.”

In the days that followed, Thorne Manor became a place of methodical tests, as if Aurelia had turned her father’s insult into an experiment. She sent Kale to the swamp fields, not because he deserved punishment more than the others, but because she recognized fire in him and wanted to see whether it would burn out or burn brighter when starved of oxygen. The overseer reported back with relish. “He fights,” the man said. “He won’t bow.”

“Does he work?” Aurelia asked.

“He works,” the overseer admitted, disappointed.

“Then let him work,” Aurelia said. “Let the swamp argue with him.”

Ree, with his musician’s hands, she placed in the main house under the pretense of labor that required delicacy. He polished silver. He carried trays. He stood near the parlor when guests visited so the governor could show off his household’s control. At night, Aurelia would sometimes ask to hear him play the broken music box melody on the old piano in the eastern wing, not as entertainment, but as observation. She watched what happened to a person’s face when music was demanded instead of offered, how a sound meant for joy could become a leash. “Play it again,” she would say, voice mild, while Ree’s shoulders tightened as if bracing for a blow that didn’t come.

Celas, she kept closest. Not in her father’s view, not in the showy spaces of the manor, but in the greenhouse and garden behind the eastern wing where herbs grew thick and glossy. She pretended she needed muscle to haul soil, but what she truly wanted was a witness who did not look away. She asked questions as they worked, quiet ones wrapped in casual tone. “Where were you born?” “Do you read?” “Have you seen belladonna used for fever?” Celas answered carefully at first, then with growing certainty when he realized she was not asking to mock him but to measure him. He had learned letters once, he admitted, taught by an older man who’d risked punishment for the crime of knowledge. Aurelia filed that away like a precious specimen.

One afternoon, as thunder built over the marsh, her father came into her wing unannounced. His boots tracked mud onto her rug. He held a folded letter like a weapon. “Hargrove expects an answer,” he said. “He will not wait forever.”

Aurelia’s hand hovered over an open book written in her mother’s sharp script. “Tell him no,” she said.

Alistair’s mouth flattened. “You will marry, Aurelia. You will be shaped into something useful.”

Aurelia looked up, her eyes steady. “You think usefulness is obedience,” she said. “Mother thought usefulness was power. Perhaps that is why you hated her.”

The governor’s face darkened, anger flashing like heat lightning. “Your mother filled your head with nonsense,” he snapped. “Her books, her herbs, her… foreign superstitions. I allowed you this wing to keep you quiet, not to make you dangerous.”

Aurelia rose slowly, her height and presence forcing him to lean back a fraction. “Then you should have burned the books,” she said softly. “Because danger grows best in damp places.”

Behind him, the music box began its broken melody, as if the house itself had decided to laugh.

That night, the storm finally arrived. Rain slammed the roof like fists. The swamp beyond the windows churned, black water rippling under wind. Aurelia sat at her desk with three cups arranged before her, each filled with a different infusion, dark liquids that smelled of roots, bitter leaves, and something sharper. The candles guttered in the draft, making shadows dance along the walls as if figures were pacing. Celas stood near the door, hands tense at his sides, watching her with careful eyes.

“What is this?” he asked, voice low.

“A choice,” Aurelia said. She tapped the rim of one cup. “My mother believed the body is not merely flesh. It is a gate. It can be opened. It can be… persuaded.”

Celas swallowed. “Ma’am, gates work both ways.”

Aurelia’s mouth twitched, almost a smile. “Yes,” she said. “And I have been locked in mine my entire life.”

She rose and crossed to him, not rushing, but with that deliberate grace that made people step aside without knowing why. “Do you know what it is to be looked at as if you are only one thing?” she asked. “A body. A burden. A joke. A commodity.”

Celas’s eyes hardened with truth. “Yes,” he said.

Aurelia held his gaze. “Then you understand why I will not be sold to Hargrove like a broodmare,” she whispered. “I will not be managed. I will not be traded. Not again.”

Outside, thunder cracked. The sound rattled the glass in her windows and for a moment made the manor feel like a ship caught in a violent sea. Aurelia turned back to the cups. “Three destinies,” she murmured. “One will bind. One will break. One will… disappear.”

Celas took a step forward despite himself. “You don’t have to do this,” he said, and the words came out with a roughness that suggested he was afraid of his own courage. “Whatever you think this is, it won’t make you free. It will only make you alone.”

Aurelia’s eyes flicked to him. “Alone,” she repeated, tasting the word again, but this time as if it carried a kind of peace.

When she spoke next, her voice held a command that made his skin prickle. “Bring Kale,” she said. “Bring Ree.”

Celas hesitated, then said, “If I refuse?”

Aurelia’s gaze sharpened, and for the first time Celas saw something raw beneath her calm, a hunger that had nothing to do with desire and everything to do with survival. “Then you will watch your friends die,” she said quietly, “and you will know it was your choice.”

The cruelty of it landed between them like a dropped blade. Celas’s jaw clenched, pain flashing across his face not because he believed she would punish him, but because he believed she was telling the truth. He left the room with the storm’s roar behind him and returned minutes later with Kale and Ree, both soaked from the rain, chains clinking. Kale glared, shoulders squared as if ready to fight the world. Ree looked around the room with the wary eyes of someone who recognized a trap too late.

Aurelia did not speak at first. She simply watched them, studying their breathing, their stances, the twitch of muscles that revealed fear or anger. Then she said, “Tonight, you will drink.”

Kale’s lips curled. “And if we don’t?”

Aurelia stepped closer, and the candlelight made her eyes look almost black. “Then my father will choose,” she said. “And his choices are always uglier than mine.”

Ree’s voice cracked. “What is in those cups?”

Aurelia’s fingers hovered above them like a conductor poised to begin. “A bargain,” she said. “And you have all been paying bargains your whole lives without being told the price.”

The room felt smaller, the storm outside pressing against the walls as if the swamp wanted in. Celas watched, helpless, as Aurelia lifted one cup and offered it to Kale. Kale stared at it, then at her, then did something that surprised everyone. He laughed, a short, bitter sound. “You think you’re different,” he said. “Because you read books and hide from your father. But you’re still Thorne.”

Aurelia’s face did not change. “Drink,” she said.

Kale lifted the cup and threw it, not at her, but against the wall. The liquid splattered, steaming faintly as it hit the wood, and for a moment it looked like the wall itself recoiled. The candles flickered hard. Aurelia inhaled once, and something like satisfaction crossed her features.

“Good,” she murmured. “Rebellion, then. I wondered if the swamp had already eaten it out of you.”

She turned to Ree and held out the second cup. Ree’s hands shook as he took it. He looked at Celas, eyes pleading, then drank, wincing as if the bitterness scraped his throat. Within moments his face paled, sweat breaking across his brow, and the sound that came from him was not a scream but a strangled, voiceless gasp. He grabbed at his neck, mouth opening, closing, as if searching for air that refused to arrive.

Celas surged forward, horror flooding him. “Stop!” he shouted.

Aurelia’s hand snapped out. “Hold him,” she ordered, voice sharp as a whip.

Kale, despite himself, grabbed Ree’s shoulders to keep him from collapsing. Ree’s eyes rolled back, then focused again, wet with tears. He made a sound like a broken instrument trying to play. Aurelia watched with a scientist’s stare, counting, listening, noting each tremor. Finally, she moved closer and pressed her fingers to Ree’s throat with almost gentle precision. Ree’s breathing steadied, shallow but present, and his voice did not return. When he tried to speak, only a rasp emerged.

Aurelia stepped back. “The voice can be taken,” she whispered, more to herself than to them. “Just as easily as it can be given.”

Then she faced Celas with the third cup in her hands. It was darker than the others and smelled of earth after rain. “You,” she said.

Celas stared at it. “Why me?”

Aurelia’s eyes held a strange honesty. “Because you see,” she replied. “And because you understand more than you want to.”

Celas’s hands trembled, but he did not reach for the cup. “Ma’am,” he said, voice thick, “if you do this, you’ll carry it forever.”

Aurelia’s shoulders lifted in a small shrug that looked almost like surrender. “I already do,” she said. “Drink.”

What happened next was not a spectacle of flesh, not something meant to titillate or entertain. It was something colder: a ritual of power, consent twisted by chains and hierarchy until it meant nothing at all. Aurelia led Celas into the bedroom adjoining her study, the storm’s roar muffled by heavy curtains, the music box’s broken melody threading through the air like a warning. She spoke low, words from her mother’s books, and the candlelight painted her face in gold and shadow. Celas stood rigid, jaw clenched, eyes shining with fury and fear and a kind of grief that had no place to go. When the door closed, the house seemed to hold its breath.

By morning, the storm had passed, leaving the world rinsed but not clean. The swamp steamed under pale sunlight. Aurelia emerged into the hall looking changed in a way nobody could explain. Her eyes were brighter, her posture straighter, her skin flushed with something like life. She moved as if a weight had been shifted, not removed, but transferred. Celas followed behind her, face blank as a mask, wrists still chained, but now the chain was less a restraint than a reminder: You will carry this secret, because I say so.

Ree sat by the window in the servants’ corridor, hands clasped, mouth moving in silent words that would never reach sound again. Kale stood in the courtyard with mud on his boots, staring toward the swamp as if calculating whether the water was deep enough to bury a man’s rage. When he saw Celas, Kale’s eyes narrowed. “You alive?” he asked.

Celas’s voice came out quiet and cracked. “Alive,” he said.

“And her?” Kale spat.

Celas looked toward the eastern wing where Aurelia’s silhouette moved behind the curtains like a shadow with purpose. “More alive than she was,” he answered, and the bitterness in his tone made Kale flinch.

The governor returned from Charleston that afternoon, riding hard, coat splattered with mud. He strode into the house with a letter in hand, ready to enforce obedience. But when he reached Aurelia’s wing, he slowed. The air there smelled different, not of books and herbs alone, but of something older, like earth turned up from a grave. Aurelia met him in the hallway, calm as still water.

“You will marry Hargrove,” Alistair began.

Aurelia interrupted him with a smile that made the hairs on his arms lift. “No,” she said.

His anger rose fast. “You insolent—”

Aurelia stepped closer, and her voice dropped into a tone that felt like a key turning in a lock. “You taught me that power is taken,” she said. “So I took it.”

The governor’s face blanched as if blood had been drained from it. His mouth opened, but his words faltered. He tried again, but his voice cracked, a thin rasp. His hands flew to his throat in panic, fingers digging as if he could claw his voice back out. Aurelia watched him with the same calm attention she’d used on Ree the night before.

“Where is it?” he wheezed.

Aurelia leaned in. “In the same place you kept mine,” she whispered. “In your control.”

Alistair staggered back, eyes wide, and for the first time the governor looked like what he truly was beneath the title: a man terrified of losing the one thing he’d mistaken for identity. He stumbled into the wall, knocked a portrait askew, and the sound of its frame striking wood echoed like a gunshot. Servants hurried, but Aurelia lifted a hand and they froze, trained by years of fear to obey the nearest authority. Aurelia had become that authority in a single night, and the speed of it made the household dizzy.

The governor did not die that day, not immediately. He deteriorated the way the manor did, quietly, damp seeping into him. His voice never returned, and without it his power began to leak away. Overseers grew bolder. Charleston officials asked questions he could no longer answer. Letters arrived demanding decisions. The plantation’s machinery of cruelty, so reliant on a man’s loud certainty, began to grind and misfire when that certainty turned into silence. Aurelia sat in the governor’s chair at meetings, not as a daughter filling in, but as something colder: a ruler who had learned the language of domination too well.

And yet, if the swamp always wanted more, it also remembered. Kale tried to run two weeks later, choosing the rice fields at dawn when fog hid the world’s edges. He made it halfway to the willows before shots rang out. Aurelia arrived after, not breathless, not frantic, only thoughtful. She looked down at Kale’s body, eyes narrowed as if disappointed by a failed hypothesis. Then she ordered the overseers to drag him toward the water, and the mud took him without ceremony.

Ree followed not long after, not by running but by fading. Without his voice, he became smaller in the house’s eyes, less noticed, less human to them. One morning he simply did not wake, his face turned toward the window as if listening for a song he could no longer play. Aurelia stood over him and said nothing, but later that night the servants saw her slip out toward the swamp with two men carrying a wrapped bundle. The water accepted that bundle too, black and quiet.

Celas remained. He moved through the days like a man half-present, hands working, eyes observing, mind storing everything. Aurelia kept him close, sometimes calling him into her study to read aloud from her mother’s books, forcing him to lend his voice to words that had become weapons. Each time he read, he felt the chain tighten around his lungs, not from iron but from knowledge of what had been done. “You hate me,” Aurelia said once, not as accusation but as curiosity.

Celas looked at her, the storm of his own eyes reflecting hers. “I hate what you chose,” he answered.

Aurelia’s mouth curved, almost sad. “Choice,” she repeated. “Isn’t it a strange word when you’ve never truly had it?”

Celas’s voice sharpened. “You had more than we ever did,” he said. “And you used it to become your father.”

For a moment, something flickered in Aurelia’s face, a crack in porcelain. Then it smoothed again. “Perhaps,” she said. “Or perhaps I became what I had to become to survive him.”

Celas leaned forward, chains clinking softly. “Survival that costs other lives isn’t survival,” he said. “It’s just hunger.”

That word landed. Hunger. Aurelia’s gaze drifted toward the window, toward the swamp steaming under sun, toward the willows hanging like mourners. “The swamp always wants more,” she murmured. “My mother used to say the land remembers every debt.”

“Then it will remember you,” Celas said.

It was months later, when the governor finally collapsed, that the house’s strange balance shifted. Alistair Thorne fell in his study, his hand still clutching a quill he could no longer use, and the man who had ruled by voice died without one. Charleston sent officials. Cousins arrived, hungry for inheritance. Ministers came to speak of God, their prayers floating uselessly in the damp air. Aurelia stood at the head of it all like a pale statue, receiving condolences as if they were coins someone insisted on paying her.

But grief, real grief, does not sit politely in a parlor. It leaks. It stains. It finds cracks. On the night after her father’s burial, Aurelia went alone into her mother’s trunk room and opened the oldest chest, the one she’d always kept locked. She drew out the silver charm, turned it in her fingers, and for the first time in years her hands shook.

Celas, sent to fetch her, found her there with candlelight trembling across her face. “You’re afraid,” he said quietly, surprised by his own gentleness.

Aurelia laughed, a thin sound. “I have not been afraid in months,” she replied. “Not since I learned how to take.”

“And what did it give you?” Celas asked.

Aurelia stared at the charm as if it might answer. “Space,” she whispered. “Breath. A life that belongs to me.”

Celas’s gaze softened, not forgiving, not forgetting, but seeing the human beneath the monster. “And what did it cost?” he asked.

Aurelia’s eyes filled with something that looked like tears but didn’t fall. “Everything,” she said.

In that moment, something shifted again, not in the manor’s power but in Aurelia’s posture. She looked suddenly very young, not twenty-one but the child who had begged for her mother’s books, desperate for something that felt like belonging. She closed the chest and straightened. “You will leave,” she said to Celas, voice firm.

Celas blinked. “What?”

Aurelia took a small key from her pocket and pressed it into his palm. “The gatehouse,” she said. “There is a horse. Papers signed. A name you can take that is not Thorne’s property.” She swallowed, jaw tightening as if forcing the words through a narrow passage. “Go north. Don’t look back.”

Celas stared at her, suspicion warring with hope. “Why?” he demanded.

Aurelia’s mouth tightened. “Because if you stay,” she said, “you will either kill me or become like me. And I… I have already made enough of myself.”

Celas’s voice dropped. “And you? What will you do?”

Aurelia’s eyes slid toward the eastern wing, toward the music box, toward the swamp beyond the windows. “I will remain,” she said. “This house is hungry. I fed it. Let it have me too, if it wants.”

Celas clenched the key, the metal biting into his skin. “This doesn’t undo anything,” he said, anger rising again because hope felt like an insult after so much loss.

Aurelia nodded once, and in that nod was more truth than she had spoken in years. “No,” she agreed. “It doesn’t. But it changes what happens next.”

Celas left before dawn, moving through fog that clung to his clothes like hands. He rode hard past willows and fields and the black water that seemed to watch him go. He did not look back at Thorne Manor, not because he didn’t want to, but because he knew looking back was how the swamp pulled you under. As the road rose toward drier land, he felt air in his lungs that did not taste like rot. He felt, for the first time, the faint outline of a future.

Years later, stories would drift through Charleston about the Thorne estate. Some said Aurelia vanished into the swamp one night, her candlelight seen bobbing among reeds like a ghost. Some claimed the manor was cursed, that men sent to manage it grew sick, their voices fading, their strength draining as if the land itself drank them. Others insisted the Thorne line endured through distant relatives, that wealth always finds a way to reproduce itself. All of it was half-true, the way legends tend to be: stitched together from fear, greed, and the stubborn refusal to say the real names of what happened.

But the swamp did keep the truth, in its own dark way. It held Kale’s rage and Ree’s stolen music and the memory of Celas’s chains. It held the governor’s silence and Aurelia’s hunger and the price they all paid when power was treated like a birthright instead of a sin. And somewhere far north, in a place where the air smelled of snow instead of rot, a man who once answered to the name Celas spoke other names out loud, insisting they be remembered. He used his voice not as a weapon, but as a lantern, because he had learned in the wet low country what happens when darkness is allowed to speak alone.

THE END

News

SHE WAS GAMBLE-WON AT EIGHT, BUT HER SISTER HAD THREE HOURS TO STEAL HER BACK

Silverton, Colorado Territory, 1877, did not wake gently. It woke like a struck match, all at once, with smoke and…

THE WIDOWER WHO MARRIED THE “TOO FAT” BRIDE LEFT AT THE RAILROAD STATION

The train pulled away with a groaning hiss, as if even the iron wheels felt guilty about leaving her there….

LONELY RANCHER “BOUGHT” A DEAF GIRL FROM HER DRUNK FATHER—THEN REALIZED SHE COULD HEAR IN A WAY THAT CHANGED THEM BOTH

Texas, 1881 wore its late-autumn heat like a stubborn secret. Even when the calendar insisted the year was cooling, the…

They Dumped the Beaten Mail-Order Bride in the Dirt – Until a Mountain Man Said “Come With Me”

The letter arrived in Boston folded like a small dare. Grace O’Malley held it over her sewing table as if…

THE COWBOY SPENT TWO DOLLARS ON THE WIDOW NO ONE WANTED — AND FOUND HIS ONLY HOPE

The stove in the back of the saloon hadn’t worked right all afternoon, so the heat came in patches: a…

THE “TOO-HEAVY” GIRL MARRIED THE “DEMON” OF CROWTOOTH RIDGE, THEN LEARNED WHO THE REAL MONSTER WAS

Declan’s words sat on the table with the smell of coffee and rabbit fat, heavy as an iron pan. “I’ll…

End of content

No more pages to load