On the morning of April 3rd, 1851, St. John the Baptist Parish woke to a silence that felt staged, like the world itself was holding its breath for the punchline.

In the center of town, in the square where men sold cotton and lies in equal measure, the stake still stood blackened from the night before. The rope that had held the condemned in place dangled loose, ends frayed like chewed nerve. Ash drifted in lazy spirals over the packed dirt. The smell of smoke clung to everything, sharp and bitter, refusing to be scrubbed out of the air.

They had expected bones.

They had expected the clean certainty of a body, the kind of certainty that let a community sleep again.

Instead, they found only char and scattered remnants of what looked like clothing, and marks in the mud that should not have existed. Footprints. Human footprints. Leading away from the ashes in a straight, unhurried line, as if the man who had supposedly burned had simply stood up, brushed off the fire, and gone for a walk.

Some of the townspeople stared at those prints like they were a scripture they could not read.

Others muttered words the church would not approve of: conjure, hoodoo, devil-work.

The sheriff, a thick-necked man who believed every problem could be solved with a rope and an audience, crouched and pressed his palm into the damp earth. He looked up, face pale in the morning light, and spoke the thought that had lodged in every throat.

“He’s gone.”

No one said the name out loud. Names had weight, and weight was dangerous when your hands were already shaking.

But everyone was thinking it.

Solomon.

Three days later, Master Edmund Bowmont was found in his locked study at Bellere Plantation, mutilated beyond recognition. The door had been barred from the inside. The windows were latched. Guards swore no one had entered, no one had left.

And yet, there he was.

A man with a fortune in land, a reputation for culture, and a private history of cruelty so ordinary it had become invisible, reduced to something unholy and final.

By then, the count was seven.

Seven men dead in total. Three executions survived. One slave who refused to die until his mission was complete.

But the story did not begin in the square, or in the smoke, or in the locked room that should have been safe.

It began six months earlier, where the Mississippi River bent like a serpent and the air hung heavy with humidity and horror, and a plantation called Bellere spread across two thousand acres of cotton country worth over four hundred thousand dollars in that year’s money.

It began with a boy.

And a promise.

Spring of 1851 was the kind of spring Louisiana sold to strangers: green and lush, full of birdsong and bright river light. But Bellere Plantation had its own seasons, and they did not care what the calendar said.

The big house rose three stories high, white columns gleaming under a sun that burned without mercy. It looked like elegance from the road. Up close, it looked like a monument built to convince its owner that violence could be made respectable if it wore the right paint.

Out in the fields, one hundred eighty enslaved people worked from dawn until their bodies gave out, hands bleeding from cotton bolls, backs knotted, eyes fixed on the ground because looking up could be interpreted as challenge. The whipping post stood near the quarters like a piece of furniture. The wood was stained so dark from old blood it looked almost black.

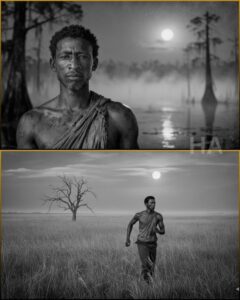

And among the people moving through that heat and fear was a man the others watched with a mixture of awe and dread, not because he was loud, not because he picked fights, but because something in him felt… unbroken.

His name was Solomon.

He was thirty-eight years old, six foot three, forged at the blacksmith’s anvil into a shape that made overseers swallow hard. His hands could bend iron. His back bore the scars of two hundred lashes. And his eyes held something that made even cruel men feel briefly, inconveniently human.

Not defiance. Defiance was a flare. It burned fast and got you killed.

This was older. Colder. Patient.

Solomon had been born in Virginia, son of a Yoruba woman captured in 1810 and dragged across the Middle Passage pregnant. His mother, Abeni, had been a healer in her homeland, keeper of knowledge about herbs, spirits, and the thin places where the living brushed against the dead.

At Bellere, they called that knowledge witchcraft.

They called anything they did not understand witchcraft. It was easier than admitting the world was larger than their rules.

Abeni died when Solomon was twelve, whipped to death after she treated enslaved children the plantation doctor had given up on. Before her final breath, she pulled her son close, cheek pressed to his, voice thin but steady.

“Our people cannot be destroyed,” she whispered in Yoruba. “We bend like river. We survive what should kill us. Remember this when darkness comes.”

Solomon remembered.

He was sold four times by age thirty. First when his mother died and the Virginia master wanted to erase her memory like a stain. Then to Mississippi, where fever nearly took him. Then to a trader who saw profit in his size. Finally to Master Edmund Bowmont of Louisiana, who paid eighteen hundred dollars in 1848 for a prime field hand with blacksmith skills.

Bowmont was the sort of man who donated to the Catholic church and quoted Shakespeare, as if those things could be used like soap. He attended opera in New Orleans and spoke with the lazy confidence of someone who believed refinement excused brutality.

He also branded his initials into the shoulders of newly purchased slaves.

He believed Black people felt pain differently than white men.

He had personally overseen the deaths of at least fifteen enslaved people in ways official records called “disciplinary accidents.”

His wife, Constance, was worse in the way quiet cruelty can be worse. She burned the hands of house slaves who broke dishes, believing fear made them careful. The scars on their palms told a different story: fear made them clumsy. Fear made them flinch. Fear made them human in ways the big house hated to acknowledge.

But the true monster of Bellere was the overseer, Jackson Thorne.

Thorne was poor white trash clawed into power with a whip and a willingness to do what wealthier men preferred not to witness. Thirty-four, lean as a starving dog, pale eyes reflecting no light, hands always drifting toward his belt where braided leather hung coiled like a sleeping snake.

He had a quota: two hundred pounds of cotton a day. Anyone short received ten lashes per pound. Anyone who spoke back got fifty. Anyone who ran got a hundred if they survived the dogs.

And Thorne had a tree.

An ancient live oak near the quarters, branches spreading like arms of death, moss hanging like gray hair. Thorne called it his teaching tree. He had hanged seven enslaved people from it in five years, always with Master Bowmont’s approval, always with the others forced to watch, bodies left swaying for days like a lesson you could not escape.

Solomon knew that tree intimately. He had watched his friend Josiah hang in 1849, choking slowly because Thorne liked a long rope that did not break the neck cleanly. It took almost ten minutes. Children cried in their mothers’ arms. Men looked away and were whipped for it. Women stared because they had learned that sometimes staring was the only way to keep your soul from leaving your body.

That day, something hardened in Solomon’s chest.

Not rage.

Rage was hot and stupid.

This was cold and deliberate, like a blade being sharpened in darkness.

Still, Solomon had a reason to endure, a reason to wake each morning despite the horror. A reason to keep the fire in his chest banked and controlled.

His son Jacob.

Eight years old, born to Sarah, a house slave who died bringing him into the world. The boy had his mother’s gentle eyes and his father’s stubborn spirit, a mind that held questions like birds hold song.

Jacob worked as a stable boy, caring for Bowmont’s horses. Light work by plantation standards, which only meant he might live long enough to understand what had been stolen from him.

Each evening, Solomon saw Jacob and taught him quietly, passing down what Abeni had given him: the names of plants that could heal or kill, the stories of ancestors, the idea that freedom was not a fairy tale but a living thing that could be found if you listened hard enough.

One night in their cabin, Jacob’s small hand wrapped around Solomon’s scarred one, the boy asked the question that always came sooner than a parent wanted.

“Papa,” Jacob whispered, “will I be a slave forever?”

Solomon looked at his son’s face, still soft with childhood, still capable of innocence. He felt pride, and terror, and a kind of grief that did not yet have words.

“No,” he said, voice steady because it had to be. “One way or another, you’ll be free. I promise you that.”

He did not know then how prophecy can be a knife that cuts both ways.

Life at Bellere followed cotton’s rhythm: planting, chopping, picking, the gin house running day and night. Solomon worked the forge, making and repairing tools, shoeing horses, fixing wagon wheels, forging chains.

The irony was a constant ache: his hands created the very instruments of bondage.

But the forge gave him something else too. Access to metal, fire, privacy, and the kind of respect that came from being essential. Bowmont even allowed Solomon a small privilege: Sunday afternoons off to pursue his craft.

Bowmont believed the forge soot had blackened Solomon’s mind enough to keep him docile.

Bowmont did not understand that Sundays were when Solomon became dangerous.

Deep in the swamp where cypress trees rose from black water and Spanish moss hung like curtains, Solomon built a small shrine. He carved symbols into wood. He left offerings of tobacco and rum. He spoke in Yoruba to ancestors he had never met but felt in his bones.

And he was not alone.

Old Ezekiel, seventy if he was a day, mostly blind, too old for fieldwork, survived as the plantation’s unofficial healer. Bowmont tolerated him because Ezekiel’s poultices kept enslaved people healthy enough to work. What Bowmont did not know was that Ezekiel was a root doctor, a conjure man who carried secrets older than the big house.

Ezekiel watched Solomon for three years before speaking to him directly. Then one Sunday, as Solomon knelt at his shrine, the old man appeared out of swamp shadow as if called.

“Smoke through the trees,” Ezekiel rasped. “Your mama was a ben.”

Solomon stiffened, hand moving toward the knife he always carried.

“How do you know that name?” he demanded.

Ezekiel’s milky eyes fixed on him in a way that made Solomon’s skin prickle. “Because I helped birth you, boy. Virginia, 1813. Your mama screaming in Yoruba while the white doctor stood useless. I was there.”

Solomon’s throat tightened. The past, usually a locked room, had opened.

Ezekiel leaned closer. “And I see death following you. Big death. But also something else. Something old and powerful. You got purpose, Solomon. Dark purpose. You gonna need help when time comes.”

From that day, Ezekiel taught Solomon deeper mysteries. How to slow his heartbeat until it nearly stopped. How to mix herbs that let the body endure pain it should not survive. How to prepare a mojo bag so potent, Ezekiel claimed, death itself would have trouble taking you until a sworn task was done.

“But it come with a price,” Ezekiel warned. “You ask ancestors for protection, you become theirs. You walk between worlds. Living but not alive. Dead but not gone. Till you finish what you swore.”

Solomon listened. Learned. Waited.

He did not know what he was waiting for, only that Abeni’s dying words echoed in his mind like a drum.

Remember this when darkness comes.

The darkness came on October 15th, 1850.

A well-dressed stranger arrived in an expensive carriage. Bowmont invited him into the study with the eager smile of a man about to turn human suffering into cash. The stranger was Marcus Doyle, a slave trader of particular ruthlessness, specializing in the Deep South trade where life expectancy was measured in years.

That evening, as the sunset painted the sky the color of fresh blood, Bowmont called all enslaved people to the yard.

Solomon stood with Jacob beside him, his son’s hand gripping his. Bowmont stood on the porch, Thorne at his shoulder, Doyle slightly behind, smiling like a man admiring livestock.

“I have an announcement,” Bowmont said. “It has come to my attention that some of you have been engaging in forbidden activities. Specifically, learning to read.”

A cold fist closed around Solomon’s heart.

Three months earlier, he had begun teaching five younger enslaved people to read, using torn pages from an old Bible he found in the trash. Reading was forbidden by Louisiana law, punished by whipping or worse. They had met in the swamp. Burned pages after each lesson.

Someone had told.

Solomon’s eyes found Samuel, the driver, a man promoted just enough to forget who he was. Samuel stood apart, avoiding eye contact, wearing his small privilege like armor.

“This cannot be tolerated,” Bowmont continued. “Education fills a slave’s head with ideas above his station. The ringleader must be punished.”

Thorne stepped forward, whip in hand.

But Bowmont was not looking at Solomon.

Bowmont was looking at Jacob.

Solomon’s body moved before his mind caught up.

“No,” he said, the word tearing out of him.

Bowmont’s eyes slid to Solomon, and something like satisfaction flickered there. “Ah, Solomon. Yes, you were the teacher. But I don’t want to damage you. You’re too valuable at the forge. So we’ll use a different method of correction.”

Thorne moved toward Jacob.

Solomon surged forward. Men grabbed him. Chains snapped onto his wrists. He threw two off, but more came, clubs and bodies and the weight of a system built to crush the human will. They drove him to his knees.

“Please,” Solomon begged, not caring who heard. “Please, master. He’s just a boy. Take me instead.”

“That’s exactly the point,” Bowmont said calmly. “Your pain means nothing to you. But his pain will teach you.”

They dragged Jacob to the whipping post. The boy did not cry at first. He looked at Solomon with eyes far too old for eight years.

“It’s okay, Papa,” Jacob said clearly. “I’m not afraid.”

That made it worse.

Bowmont lifted a branding iron already glowing red, warmed by Solomon’s forge fire.

“No brand heals,” Bowmont said. “He’ll carry this reminder forever.”

Solomon made a sound that was half prayer, half animal.

Bowmont pressed the iron to Jacob’s back.

The smell hit first, then the scream, high and thin and terrible, a child’s world turning into pain. The iron stayed longer than it needed to, as if Bowmont wanted time to savor the lesson.

When he pulled it away, the initials E.B. were seared into Jacob’s small body, flesh charred and blistering.

Jacob sagged, whimpering.

Bowmont looked at Doyle. “And of course, a marked slave who can read is a liability. Questions might be asked. Mr. Doyle has offered eight hundred dollars for a young, healthy boy.”

“No.” Solomon’s voice went flat, emotion compressed into something diamond-hard. “You can’t sell him. He’s my son.”

“He’s my property,” Bowmont corrected. “And I can do with my property as I please.”

They cut Jacob down. The boy could barely stand. Doyle examined him like a horse.

“He’ll heal,” Doyle said. “Young ones adapt well once you break their spirit.”

Jacob looked at Solomon, finally frightened. “Papa… what’s happening?”

Solomon fought the chains until blood ran down his wrists. “Jacob, son, I’ll find you,” he swore, words cracking. “I swear to God I’ll find you.”

A club struck Solomon’s skull and knocked the world sideways.

When his vision cleared through blood and tears, he saw Jacob led to Doyle’s wagon. Jacob looked back once, face streaked with tears and pain, mouth forming Papa without sound.

Then the wagon rolled away, taking the boy toward Mississippi, toward cotton fields that ate children.

The crowd dispersed, silent, because grief was dangerous when the master was watching.

Solomon stayed on his knees in the dirt until night came.

When he finally stood, his face looked empty. His eyes looked dead.

He walked back to the cabin he had shared with Jacob, where the boy’s pallet still held the shape of his small body, and in that darkness Solomon made a decision.

He would not run. He would not beg. He would not break.

He would make them pay.

And he would not die until it was done.

He reached under his shirt and found the leather cord around his neck. A small pouch hung there, a mojo bag his mother had made long ago. He had not opened it in years.

Now he did.

Inside were three items: graveyard dirt, a piece of High John root, and a scrap of paper marked with symbols in Abeni’s hand. There was one symbol Solomon had never fully understood until this moment.

Walking between worlds.

Refusing death.

Becoming something other than human.

Solomon cut his palm and let blood drip onto the paper. He whispered in Yoruba, words that were prayer and curse braided together.

“Ancestors, hear me. My son has been stolen. My people suffer. Seven men participated in this crime. Seven men will die by my hand. And I will not die until this oath is fulfilled. Take me. Use me. Make me your weapon.”

The wind slid through the cabin’s cracks, carrying swamp smell and something colder, older.

When Solomon opened his eyes again, they reflected no light at all.

For weeks afterward, Solomon moved through Bellere as if nothing had happened. He worked the forge. He ate little. He spoke less. But his stillness was not resignation. It was calculation.

He began with preparation. The forge offered cover for making tools that could become weapons. A sharpened cotton hook. A chain modified for strangling. Knives hidden in places only his hands knew. Each item made quietly, disguised as ordinary labor.

Then he studied routines. Bowmont’s habits. Thorne’s patrol. Samuel’s pride. The neighboring men who had watched Jacob burn and nodded approval.

Solomon’s targets were clear: Edmund Bowmont. Jackson Thorne. Marcus Doyle. Samuel. And three neighboring plantation men who had witnessed the branding as if it were theater.

Seven.

But Solomon needed more than weapons.

He needed endurance.

On a moonless night in early November, he went to Ezekiel.

“I need the ritual,” Solomon said. “The one that keeps death away.”

Ezekiel’s blind eyes seemed to see into him. “You swore an oath. I can smell it. Seven deaths. You wanna walk between worlds till it’s done.”

“You know the cost,” Ezekiel warned. “You become theirs. Your fear won’t exist. Your pain won’t matter. You’ll do terrible things and feel nothing. And when it’s over, you still gotta live with what you became.”

Solomon thought of Jacob, branded and sold. Thought of Abeni dying under a whip. Thought of Josiah’s legs kicking under Thorne’s tree.

“I’m already in that dark place,” he said. “I just need the door to stay open until I finish.”

Ezekiel nodded, slow and heavy. “Seven days of preparation. No questions. On the seventh night, we bind it.”

Solomon fasted, drinking only water mixed with bitter herbs. At dawn and dusk, he went into the swamp and spoke to his mother in Yoruba, telling her what had been done, what he planned to do, begging for strength he could not find in himself anymore.

Each day, Ezekiel gave him a symbol to carve into his skin where clothes would hide it: protection, strength, courage, connection, purpose, patience, and finally the mark of walking between worlds.

By the seventh night, Solomon looked carved down to something essential: lean, hard, eyes burning.

In the deepest swamp, Ezekiel prepared a space with candles of animal fat, white clay symbols in mud, offerings for spirits that did not care about white men’s laws.

“Lie under the water,” Ezekiel commanded. “Hold your breath till you find where death touch you. Then come back.”

Solomon sank into black water. The world narrowed. His lungs burned. Then, strange peace. His heartbeat slowed, slowed, nearly stopped.

In that quiet, he felt presence: Abeni first, then a line of ancestors stretching back like a river into darkness. They watched him without pity, without softness, as if asking the only question that mattered.

Are you serious?

When hands hauled him out and he gasped air like it was the first breath of his life, Ezekiel pressed a red cloth bag into Solomon’s palm.

“This your mojo,” Ezekiel said. “Graveyard dirt from a warrior’s grave. High John root. Sulfur. Devil’s shoestring. Lodestone. You wear it always. While your oath unfulfilled, death gonna have to work to take you.”

“And when I finish?” Solomon asked, voice rough.

Ezekiel’s face tightened. “Then you just a man again.”

Solomon slipped the bag around his neck and tucked it under his shirt, where it rested against his heart.

He went back to Bellere at dawn, and began his day’s work.

And the hunt began.

The first death came near the end of November, when Colonel James Whitmore left Bellere late after bourbon and business talk. He rode alone down a road tunneled by live oaks. Solomon stepped out of shadow at the one place where the trees closed tight, and the horse reared, and the world became simple.

Afterward, Solomon dragged the body into swamp water and let it disappear.

Two days later, Whitmore’s horse returned home riderless, and white men began to whisper that something was wrong.

The second death came a week later on a lonely stretch of road where Judge Horus Caldwell traveled by carriage. Solomon stopped the horses, pulled the driver down, and left the judge on the dirt staring up at the sky like a man seeing consequence for the first time.

This time, Solomon did not hide the bodies. He left them for discovery.

Let fear travel faster than truth.

By Christmas, the region vibrated with panic. Three prominent men dead. Rumors flowered into superstition. Patrols doubled. Guards drank harder. Slaves were questioned until their mouths went dry.

But suspicion stayed external because white men preferred believing danger came from “outside.” It kept the world orderly in their heads.

That illusion cracked when Thorne and Samuel died on New Year’s morning.

Solomon did not do those alone. That night in Ezekiel’s cabin, twenty-three people gathered, drawn together by grief and fury sharpened into resolve. They were not a mob. They were a wound that had decided to speak.

Thorne died on his teaching tree, strangled by the same rope he had used on others, left hanging as the sun rose, a message carved in the language masters understood best: consequence.

Samuel died in the quarters under the eyes of people he had betrayed, his privilege stripped away like skin.

By dawn, Bellere had become a battlefield made of whispers.

Bowmont emerged pale and shaking, realizing the rules had shifted. He ordered every cabin searched, every person questioned.

Solomon was found at his forge, soot on his face, hands steady, offering to make new locks for the big house.

Bowmont, desperate for control, agreed.

Sometimes fear makes you accept help from the very thing hunting you.

When Marcus Doyle returned in mid-January, he arrived with guards and paranoia, but bourbon softened caution. On the second night, the guards drank, and Doyle slept heavy.

Solomon slipped into the guest house through a window left open for air, and when Doyle’s eyes snapped wide in terror, Solomon did not offer a speech.

He offered chains.

He dragged Doyle to the Mississippi and pushed him under with iron weight, letting the river swallow another man who had profited from drowning.

Six.

By morning, the plantation screamed. Chain marks led to the river. Bowmont’s face lost color.

Militia arrived by afternoon, forty men with rifles and dogs trained to hunt human beings.

They searched every cabin, every outbuilding, every patch of ground that could hide a body or a secret. Someone found bloodied rags Solomon had missed. Someone found a tool not cleaned enough.

By noon, Solomon stood in the yard surrounded by armed men.

Bowmont pointed at him like a man pointing at his own sin, made flesh.

“Seize him.”

Solomon did not run.

He had not come this far by hoping the world would be kind.

He met Bowmont’s eyes and spoke with a ruined calm.

“Your son’s name was Jacob,” Solomon said. “Everything that happened after you took him is your doing.”

Bowmont struck him, furious at being reminded he had caused his own haunting.

“You murdered six white men,” Bowmont spat.

“Six slavers,” Solomon corrected, blood on his lip. “Six demons.”

Bowmont lifted a hand to stop a soldier from shooting.

“No,” he said. “He deserves to suffer. Hang him from Thorne’s tree. Let every slave see what happens to murderers.”

They dragged Solomon to the teaching tree. The noose went around his neck. The crowd was forced to watch, because cruelty demanded witnesses.

Solomon looked out over faces filled with terror, grief, and something dangerously close to hope.

“Hanging me changes nothing,” he rasped. “When I’m gone, others will rise. Every slave you see might be the next to remember they’re human.”

Then the rope tightened.

Solomon’s world narrowed to pressure and darkness. His body kicked, then slowed. His heart stuttered.

And then, in the deep place Ezekiel had taught him, he slipped between worlds.

An hour later, they cut him down.

A soldier checked for a pulse, found none, and nodded.

They threw his body onto a cart to take him to the parish jail before they decided what public spectacle would end the nightmare properly.

Halfway there, the cart hit a rut.

Solomon’s eyes opened.

The mojo bag burned hot against his chest like an ember pressed to the soul.

He rolled off the cart into brush and vanished into the swamp, chains clanking softly, as if even iron had learned to whisper.

When the men realized the body was missing, panic spread like fire. The story traveled faster than horses: the slave was alive. The rope hadn’t taken him.

A man who couldn’t die was the kind of thing that made even armed men look over their shoulders.

They hunted him for days. Dogs bayed. Men marched with torches. Swamp water swallowed sound.

But Solomon knew how to hide. Mud and wild onion masked scent. Water erased trails. He rested in cypress crooks while hounds passed close enough he could hear their breathing.

Eventually, they caught him again near the edge of town, exhausted, throat damaged, still alive.

The sheriff wanted certainty. The parish wanted a show.

So they chose fire.

On April 2nd, they tied Solomon to a stake in the square and lit the kindling. The crowd gathered, because crowds always gather for cruelty when it wears the costume of “justice.” The priest prayed. The sheriff watched. White men congratulated themselves for restoring order.

As flame climbed, Solomon lifted his head, eyes hollow but steady, and spoke loud enough for the enslaved faces in the back to hear.

“Tell them I fought,” he said. “Tell them I didn’t kneel forever.”

Then smoke swallowed his words.

The fire burned long.

And in the morning, the stake stood empty.

Ash in the dirt.

Footprints leading toward the swamp.

And the parish, for the first time, met a fear it could not whip into silence.

Solomon returned to Bellere on the third night after the burning, moving like a man who had already died and decided death was beneath him.

His throat was ruined, but his body moved with purpose. The mojo bag now felt colder, heavier, as if the ancestors had been carrying him and were growing tired.

Bowmont did not sleep. He sat in his study with a rifle and bourbon, lamps blazing, guards outside, locks and bars newly forged by Solomon’s own hands.

Fear made Bowmont a prisoner in his own house.

He did not hear the window unlatch. Did not hear the shadow slip through.

He only felt cold steel against the back of his neck.

“Hello, master,” Solomon rasped, voice barely more than breath.

Bowmont froze so hard the bourbon trembled in his glass. “How?” he stammered. “You were dead.”

“I was dead,” Solomon said. “I’m what you made. Walking dead held together by oath.”

The chains on Solomon’s wrists clinked softly as he moved into the lamplight.

“You’re the seventh,” Solomon said.

Bowmont’s hand twitched toward the rifle. Solomon slapped it away. The gun clattered across the floor.

For the first time, Bowmont’s mask of cultured control cracked open and something raw spilled out.

“Please,” he gasped. “I’ll free you. I’ll free all of them. Money. Land. Anything.”

Solomon stared at him, and in that stare was the cruel clarity of someone who has learned that bargains offered by tyrants are just another kind of lie.

“Jacob,” Solomon said flatly. “Where is my son?”

Bowmont’s silence was the final confession. One child among thousands meant nothing to him.

Something in Solomon shifted then, not into rage, but into a kind of exhausted finality. He had carried mercy like a stone in his pocket for years. Now he set it down.

What happened in that study took time, because some debts cannot be paid quickly, and Solomon had learned patience from rivers and from chains.

When it was done, he carved one final Yoruba symbol into the wall in Bowmont’s blood: completion.

Oath fulfilled.

Seven.

The moment Bowmont’s last breath rattled out, Solomon felt the mojo bag go cold against his chest.

The protection ended.

The ancestors had held him up until the work was finished, and now they stepped back, leaving him what he had always been beneath the legend.

A man.

Mortal again.

Solomon walked out into the yard and stood under torchlight without hiding, chains still on his wrists, blood on his skin that wasn’t his.

He did not run because he was tired in a way running could not fix. He had killed seven men, and none of it brought Jacob back. Vengeance had been a fire, and fire can keep you warm, but it also burns your hands.

Men found him within minutes. Rifles lifted. Shouts cut the night.

“Bowmont?” someone screamed. “Where’s Bowmont?”

“Dead,” Solomon rasped. “Seventh and last.”

They rushed him, beat him, shackled him, dragged him into a reinforced wagon bound for New Orleans, because the white world needed to prove it still owned the ending.

As the wagon rolled away from Bellere, Solomon lay on the floor, chains biting his skin, and closed his eyes.

He had failed to find Jacob.

But he had changed something.

Fear had been a one-way road at Bellere for generations, flowing from the big house into the quarters like poison.

Now fear flowed both ways.

And sometimes, that alone was a crack wide enough for light.

Two days later, on a lonely stretch of road, the wagon was ambushed at dawn. Armed men with covered faces struck hard and fast. Guards fell. Rifles barked.

When the attackers wrenched open the wagon door, one man pulled down his mask.

Moses, the coachman from Bellere, eyes bright with the reckless courage of someone who had already decided the old rules were dead.

“Thought we’d let them kill you again?” Moses said, voice tight with something like laughter and grief braided together. “Not a chance.”

They cut Solomon free. Pressed food and water into his hands. Led him into the swamp where the world was wide and lawless and alive.

For weeks, a manhunt swept southern Louisiana. Militia. Slave catchers. Volunteer posses. Hundreds of men hunting the story more than the man.

They never found him.

They found rumors instead: overseers dead on lonely roads, traders ambushed, strange symbols carved into flesh like signatures.

And among enslaved communities, Solomon’s name became more than a person.

It became permission.

A whispered reminder that chains were not laws of nature. That masters bled. That fear could be returned.

Years later, people argued what Solomon was. Murderer. Freedom fighter. Demon. Angel. Ghost.

History, when it is written by men like Bowmont, prefers neat boxes.

But life inside bondage rarely fits neat boxes.

In some stories, Solomon died in a swamp under gunfire, and a Quaker family nursed a nameless Black man back to health in free territory, and that man spent the rest of his life guiding others north, refusing to be the weapon again unless he had to.

In other stories, he never stopped walking.

Either way, the stake in St. John the Baptist Parish stayed empty in memory long after the ash was gone.

Because people remembered the most terrifying part was not the killings.

It was the footprints.

Proof that someone the world insisted was property had stood up out of fire and chosen his own direction.

And if one man could do that, then perhaps the future could too.

THE END

News

CEO Married the Janitor — Unaware He Was a Former Elite Special Forces Commander

The boardroom at Atlas Defense Technologies had the kind of silence money buys: thick carpet, thicker egos, and a view…

“Can i share this table?”asked the one legged girl to the single dad—then he said

The first warm Saturday in late March felt like Portland was finally exhaling. After months of gray that clung to…

HE WHISPERED “SEVENTEEN DAYS” AND THE PLANTATION STARTED TO BREAK

The iron shackles didn’t just bite, they remembered. They cut into wrists thick as fence posts, the kind of wrists…

NO CHRISTMAS DINNER IN THE BLIZZARD… UNTIL THE LONELIEST RANCHER SOLD HIS LAST HEIRLOOM TO FEED A STRANGER’S CHILDREN

Milin Chen stood with her forehead against the frosted pane of the cabin window, watching Wyoming disappear. The world outside…

BILLIONAIRE FINALLY FINDS HIS DAUGHTER AFTER 12 YEARS… AND THE SIGHT SHATTERS HIM

Gregory Hammond had signed contracts that changed skylines, negotiated deals that swallowed smaller companies whole, and walked through boardrooms like…

HE CAME TO SEND HER AWAY… BUT THE TEAR ON HER CHEEK CHANGED EVERYTHING

Red Willow Station smelled like coal smoke and damp wool, the kind of place where strangers passed each other without…

End of content

No more pages to load