Eleanor felt an internal crack, the soundless fracture of something sealed too tightly for too long.

She stood there longer than she should have, watching the careful confidence of his hands, the way he spoke to the horse in a voice that carried neither fear nor bitterness. It was not softness. It was steadiness, a quiet strength that felt almost obscene inside a world designed to break men.

Her glove creaked faintly as she tightened her fingers. She did not know why her heart had started running.

“What is your name?” she asked, her voice smaller than she intended.

He did not look up. “Elijah, ma’am.”

“Elijah,” she repeated, and the name tasted like prayer and blasphemy at once.

She left without another word, carrying the sound of his voice like a hot coal in her palm.

That night, she could not eat. The food on her plate looked decorative, dead. She lay in her bed while the mansion settled and sighed around her, hearing Charles’s distant snore through the wall of their separate chambers, staring at the ceiling as if it might confess something to her. Instead she saw Elijah’s eyes, steady and unowned.

In any sensible world, that would have been the end. The governor’s wife would return to needlework and polite conversation. The enslaved man would return to the role forced upon him. The plantation would continue grinding days into profit.

The heart is not a sensible instrument. It is an animal that learns a scent and refuses to forget it.

Three days later, Eleanor found herself in the rose garden before dawn, walking as if her feet had developed their own intention. She told herself she needed air. Solitude. A moment without performance. The truth followed behind her like footsteps she did not want to hear.

Elijah was there, pruning roses with a knife that flashed in the early light. His presence in the garden was not unusual; enslaved people were everywhere and nowhere on the estate, visible only when needed, invisible when inconvenient. Yet Eleanor knew, with the uncomfortable certainty that guilt always brings, that he had been assigned to this spot, and not by accident.

“They’re beautiful,” she said, gesturing toward the blooms.

“Yes, ma’am.”

His voice was careful, almost empty, the tone of a man who had learned that words could be turned into weapons against him.

Eleanor swallowed. “Do you have… family?”

The question hung in the humid air like a trap she had not meant to set.

Elijah’s knife did not pause, but something in his shoulders hardened. “Had a wife once,” he said quietly. “Sold off seven years back. Alabama, I heard. Had a little girl too. Never knew what happened to her.”

Eleanor had heard such stories at dinner tables, floating through conversations the way smoke floats through a room. Everyone knew, and everyone allowed knowing to become background noise. Hearing it from his mouth made it real enough to bruise.

“I’m sorry,” she whispered.

Elijah looked up then, truly looked at her, and what she saw was not hope or trust, but recognition: the brief acknowledgment that she had spoken to him as if he were human, as if his grief mattered.

“Sorrow don’t change nothing, ma’am,” he said. “But I thank you for it anyway.”

She should have turned back. She should have retreated into the safe scripts of her life. Instead she came again the next morning, and the next. At first they spoke little, their silence heavy with what could not be said. Gradually, words began to appear like small birds landing in a dangerous place.

She asked about roses, and he taught her names and seasons and the patience required to coax beauty from hostile soil. He spoke of pruning, of knowing when to cut back and when to let something grow, and Eleanor felt as if he were describing survival itself. She spoke of books she had read, of places she would never see, of the strange emptiness of living a life chosen by others. She never said the word lonely, but the pauses between her sentences confessed it.

The house servants noticed long before anyone else did. Enslaved people survived by paying attention, by reading subtleties white folks believed were invisible. Mama Seraphine, the cook, had served the Bowmont family for thirty-four years. She watched Eleanor rising before dawn, watched her return with a softness in her face that had not been there before. She said nothing, but she began leaving biscuits wrapped in cloth near the garden gate.

It was a kindness and a warning at once.

Because everyone on that plantation knew what happened when a white woman looked at a Black man with anything other than indifference or contempt. There were stories whispered in quarters and stables, stories of accusations made to protect reputations, stories of bodies swinging from trees because a glance had been interpreted as desire. In those stories, the man always died. Sometimes the woman did too, slower, in exile or madness. The system did not forgive the idea that its hierarchies could be crossed.

Eleanor and Elijah did not touch. They kept the physical distance the world demanded, but something else was reaching across the space between them, threading itself tighter each morning.

By late June, Governor Bowmont began to notice that his wife was smiling again. He did not know why, and ignorance made him uneasy. A happy wife was desirable; a wife with secrets was dangerous. Charles did not rage. He watched. Men like him were patient predators.

In July, the heat turned biblical. Cotton fields shimmered with mirages. Enslaved workers moved through the rows like ghosts, bodies obeying because disobedience meant pain. Inside the mansion, Eleanor felt heat as fever, as madness, as the physical shape of a truth she could no longer pretend was harmless.

Elijah was reassigned closer to the main house. The overseer, Thaddeus Cole, made the change without explanation. Cole was lean and weathered, his cruelty famous even among men paid to be cruel. He wore a whip like jewelry, a symbol that did not need to be used often to be understood.

Mama Seraphine caught Eleanor in the hall one morning, blocking her path with the quiet authority of someone who had survived long enough to stop being impressed by titles.

“Child,” she said, low. “You playing with fire that going to burn more than you.”

Eleanor’s hand tightened on the doorframe. “I don’t know what you mean.”

“Yes, you do. I seen your face when you come back from them walks. I seen that man’s eyes when you pass. Ain’t nothing good going to come from this.”

“We’ve done nothing wrong,” Eleanor said, and desperation leaked into her voice.

“Don’t matter what you done. Matter what it look like. Matter what the governor think when he find out. He always do.”

In Seraphine’s eyes Eleanor saw fear, not for scandal, but for Elijah’s life. In that world, Eleanor’s transgression could be translated into exile, humiliation, a ruined reputation. Elijah’s could be translated into rope and fire.

“I’ll be careful,” Eleanor whispered.

“Careful ain’t enough,” Seraphine replied. “You need to stop.”

But something had already shifted inside Eleanor, and both women knew it.

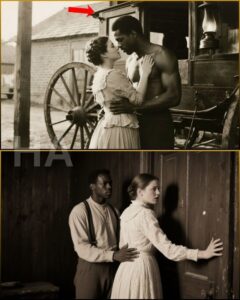

That afternoon, Eleanor found Elijah in the workshed behind the stables, repairing a wagon wheel. The space was dim and close, smelling of oil and wood shavings. For the first time since their encounters began, they were alone in a place where no one was supposed to see.

“You shouldn’t be here,” Elijah said without looking up. “They watching now.”

“I know,” Eleanor replied, and her voice broke on the words.

Elijah set down his tools and faced her. The light that filtered through the cracks in the walls caught his eyes and made them look almost metallic, forged rather than born.

“Then why you here?”

Eleanor had rehearsed a dozen answers on her walk there, all of them polite lies. None survived his stare.

“Because I can’t stay away,” she said.

Silence thickened. Elijah’s jaw tightened as if he were holding back something that could kill him.

“You know what they do to men like me who even get accused,” he said, low. “Don’t matter if it true. Don’t matter if she the one who come to him. They tie him up and…” He stopped, breath harsh. “You understand what I’m saying?”

“Yes.”

“Then you understand I can’t want this. Wanting ain’t for people like me. It’s just a way to die faster.”

Eleanor took a step closer. Her hands trembled, soft hands that had never been forced to earn softness.

“What if I wanted enough for both of us?” she asked, and hated herself as soon as the words left, hated the privilege embedded in her ability to want.

“That ain’t how the world work,” Elijah said. Then, after a beat, “Miss Eleanor.”

“My name is Eleanor,” she insisted. “Just Eleanor. When we’re alone.”

Something in his expression cracked, not into softness, but into exhausted honesty.

“You asking me to forget everything that keep me alive,” he said. “Everything I learned since I was old enough to understand my life don’t belong to me.”

“I’m asking you to remember you’re human,” she whispered. “That I’m human. That this… matters.”

Elijah’s face tightened as if grief and anger were wrestling behind his eyes.

“My daughter’s name was Grace,” he said suddenly. “I think about her every day. Wonder if she remember me. Wonder if she alive. Wonder if she growing up thinking her daddy just left her. Didn’t fight for her.” His voice caught. “I couldn’t save her. Couldn’t save my wife. I been living in chains so long I can feel them even when I can’t see them.”

Eleanor’s tears slipped down her cheeks, hot and humiliating. “I’m sorry. God, I’m sorry.”

“I didn’t say stop,” Elijah said, and the words fell between them like a match dropped into dry straw. “I didn’t say I don’t feel it. I just said it hurt.”

Then his hand lifted, slow, hesitant, as if he had forgotten the shape of tenderness.

Eleanor reached for it before he could withdraw. Their fingers met, rough callus against silk-soft skin, and the shock of contact felt like both sin and salvation. They stood like that, barely breathing, as if the world might shatter from the sound of their pulse.

Footsteps approached.

They broke apart instantly, survival moving faster than longing. Elijah grabbed his tools. Eleanor smoothed her dress. When Thaddeus Cole appeared in the doorway, they stood six feet apart, the proper distance between mistress and enslaved man.

Cole’s eyes traveled between them with the calm hunger of a man who lived on other people’s fear.

“Afternoon, Mrs. Bowmont,” he said with false politeness. “Can I help you find something?”

“I was looking for the stable master,” Eleanor lied, voice steady only because panic had made her numb.

Cole smiled as if he tasted the lie. “Stable master in the south barn. This here just a workshed. Nothing of interest to a lady.”

Eleanor walked out with dignified slowness. Cole watched her go, storing the moment like ammunition.

That night, Eleanor lay awake and felt Elijah’s hand like a ghost on her skin. On his pallet in the quarters, Elijah stared into darkness and tried to memorize what it had felt like to be touched without violence. Mama Seraphine sat by her window, praying without knowing what she wanted the prayer to accomplish.

By August, speaking was too dangerous. Cole appeared everywhere Eleanor went. Elijah was sent to the farthest fields, the hardest work, where he could be seen and controlled. The distance between them turned into a constant ache.

So Eleanor began to write.

She wrote in her private sitting room by candlelight, pouring thoughts onto paper that she could not speak aloud. At first she did not intend to send them. She told herself it was only to keep herself from drowning in silence. Two weeks passed. Then three. The hunger became unbearable.

There was a young chambermaid in the main house named Dinah, sixteen, small and quick, invisible in the way enslaved girls learned to be invisible. Eleanor approached her when the rest of the household was at dinner.

“I need your help,” Eleanor whispered, and the girl’s eyes widened with terror because white requests often carried hidden knives.

Eleanor handed her a folded letter sealed with wax. “I need you to give this to Elijah.”

Dinah stared at it as if it were a snake. “Ma’am, if they catch me…”

“They won’t,” Eleanor said too quickly, then hated herself for the blunt truth behind the confidence. “You can move in ways I can’t. Please.”

Dinah’s lips pressed together. She was calculating risk the way generals calculated battle.

“If I do this,” Dinah said, voice low, “you promise me something. When this blow up, and it will, you remember I ain’t choosing this. You remember I was scared and you the mistress and I couldn’t say no.”

Eleanor understood. Protect me when the time comes. Lie for me if you must.

“I promise,” Eleanor said. “No matter what happens.”

Dinah took the letter and hid it in her apron.

That night, in the brief sliver of time when the main house servants were allowed to breathe, Dinah slipped to the field quarters. She found Elijah sitting outside his cabin, too hot to sleep inside, staring into nothing with the thousand-yard gaze of exhaustion.

“Got something for you,” Dinah whispered, pressing the letter into his hand. “From the big house.”

Elijah held it like treasure and bomb.

By candlelight, he broke the seal and read Eleanor’s handwriting. He read it three times, throat tight with emotions he had no safe way to release. Writing back was insanity. Evidence was death. Yet he found a stub of pencil and a scrap of paper and wrote in cramped, careful script he had taught himself in secret, committing a crime just by forming letters.

The correspondence became their only place to exist honestly. Letters moved between house and field in Dinah’s sleeves, in basket linings, tucked beneath laundry. Words grew longer. They wrote about childhoods, about the shapes of cages, about books and dreams and the meaning of being seen. They avoided the word love for a long time, as if refusing to name it could keep it from becoming a noose.

It did not.

In late September, Governor Bowmont found the letters.

He was searching Eleanor’s desk for a jewelry box key, intending to borrow a necklace as a gift for a political ally’s wife. He opened a drawer and found a folded page. Curiosity made him unfold it. The first lines burned into his eyes like insult carved into stone.

Charles Bowmont stood perfectly still as he read. His face revealed nothing, because he had built a career on controlled expressions. Inside him, something cold began to unfold, a rage that was less emotion than doctrine.

He searched the desk and found eight letters in total, hidden in compartments Eleanor had believed safe. He read every word, every confession, every line that suggested a world where a Black man could be worthy of his wife’s regard.

When he finished, he folded the letters, put them in his coat pocket, and walked out onto the veranda, looking over fields that had always obeyed.

Some men would have stormed into Eleanor’s chamber and struck her. Charles did not. He was not interested in loud fury. He was interested in control, in consequence, in restoring the order that the letters dared to insult.

That evening, Eleanor returned home to a silence that felt charged, the way air feels before lightning. Servants moved quickly, eyes down, faces blank in the particular way that meant they knew something terrible.

Dinah found her in the upstairs hall, trembling. “Ma’am. The governor been in your chambers.”

Eleanor’s blood turned to ice. She ran to her desk and found drawers open, empty. The letters were gone.

Her first thought was not for herself. Elijah.

She grabbed Dinah’s shoulders. “You have to warn him. Now.”

Dinah’s tears spilled. “Too late. Cole and three men already went to get him. Governor sent them.”

Eleanor ran outside, propriety shredding behind her like torn fabric. She reached the quarters to see torchlight flickering against faces. Thaddeus Cole stood in the center. Elijah was beside him, hands tied behind his back, face bloodied.

“Stop!” Eleanor screamed. “Stop this now.”

Men turned, startled and embarrassed by the sight of a white woman in the quarters with her hair coming loose, dress rumpled, voice raw. Cole’s mouth curved with satisfaction.

“Mrs. Bowmont,” he said, “you should return to the house. This ain’t for a lady.”

Eleanor pushed closer until her eyes met Elijah’s. His expression broke her heart, not with anger, but with a quiet inevitability.

“Eleanor,” he said softly, “go back. Don’t make this worse.”

“How could this be worse?” she choked out.

A voice cut through the night, calm as a blade. “That’s enough.”

Charles Bowmont approached from the direction of the mansion, walking as if time belonged to him. His face was composed, his fury contained like acid in glass.

“Eleanor,” he said, “return to the house.”

“No.”

The word cracked the air. Wives did not refuse. Women did not defy men in public, not in that world, not in front of people the system insisted were less than human.

Charles stepped closer, voice dropping. “You will return, or I will have you carried.”

“Then have me carried,” Eleanor said. “Because I’m not leaving him.”

Shock flickered across Charles’s face, then disappeared behind contempt.

“Do you understand what you’ve done?” he asked. “Do you comprehend the humiliation? The destruction?”

“I understand,” Eleanor said, voice shaking but steady, “that I have been your decoration for fifteen years. And for the first time, I felt like a human being.”

Charles’s hand moved fast. The slap sent her head snapping sideways. Stars burst behind her eyes. She tasted blood.

Elijah made a sound like an animal hurt into rage and lunged, but men grabbed him, holding him back.

“Don’t you touch her!” Elijah shouted, the mask of submission falling away, revealing the man underneath: fierce, intelligent, alive.

Charles turned slightly toward the men as if giving a lesson. “You see,” he said, voice filled with terrible satisfaction. “You see the presumption. This animal believes he has the right to defend a white woman.”

“He is not an animal,” Eleanor said, spitting blood. “He is more decent than you will ever be.”

Charles’s smile did not reach his eyes. He pulled the letters from his pocket and waved them like proof of rot. “Love letters,” he said. “Between my wife and my property.”

He looked at Elijah. “You taught yourself to read and write. Another crime.”

“If you hurt him,” Eleanor whispered, “I will never forgive you.”

Charles laughed, genuinely amused. “With what power will you punish me? You are my wife. Legally, you are nearly my property too.”

Truth struck like a second slap. Eleanor had always known the limitations of her world in theory, but the clarity of them in this moment was sickening.

“So here is what will happen,” Charles said, voice taking on the calm of a sentence delivered. “You will go to your sister in Charleston for six months. You will return repentant, silent, grateful.”

He turned to Elijah. “As for you… the punishment for this presumption is death. But I have something more fitting.”

Eleanor’s stomach dropped.

“I am selling you,” Charles said. “Tomorrow morning. Mississippi. Harkins operation.”

Elijah’s face went pale even in torchlight. Everyone had heard of Harkins. A death sentence disguised as a sale.

“You cannot,” Eleanor whispered. “Please.”

“I can,” Charles said. “He will be worked to death slowly. And you will live the rest of your life knowing your selfishness led to it.”

Cole dragged Elijah away. Eleanor tried to follow, but hands caught her arms. In the last moment their eyes met, Elijah’s gaze steady even in ruin.

There was nothing to apologize for in his expression. Only the fierce truth that being seen had been worth the price.

That night, locked in her chamber, Eleanor wept until her body felt emptied. Around midnight, shouting rose outside. She stumbled to the window and saw flames licking at the darkness.

The quarters were burning. Storage sheds. The holding cell.

In the chaos, Elijah disappeared.

Rain began to fall just after midnight, washing away scent and footprints. Dogs were useless. Patrols returned empty-handed. By morning, Charles’s fury had nowhere to land except into tighter control, tighter lies.

Eleanor was sent to Charleston as planned. Society swallowed the story Charles fed it: a nervous breakdown, a misguided slave, a merciful husband handling scandal privately. People wanted to believe the version that kept their world intact.

Eleanor sat in her sister’s drawing room like a ghost with a living heart, listening to pity disguised as conversation, staring at windows that framed freedom she could not touch. She survived six months, then a year, then more. When she returned in the spring of 1848, she was thinner, quieter, her beauty dimmed by something that moved like grief and burned like rage.

She resumed her role with mechanical precision, the obedient wife, the recovered invalid. Divorce would have been more scandalous than reconciliation, so Charles accepted her back as if taking possession of damaged property.

There was no word of Elijah. He had not been caught, which meant either he had found the North or died without leaving a body anyone would claim.

Eleanor chose to believe the first, because the alternative would have killed what was left of her.

She began committing small rebellions. She arranged extra food to be sent to the quarters. Medicine when illness spread. She taught house servants to read behind locked doors, hiding books in her chamber. These acts did not dismantle slavery. They did not wash blood from the plantation’s foundations. They were drops thrown at a fire. Still, drops mattered to those burning.

Dinah grew from frightened courier into a sharp-eyed young woman who carried herself as if the world’s cruelty had forged her into steel.

“You think he made it North?” Dinah asked one day in 1849 while sorting dresses that felt like costumes.

“I have to believe he did,” Eleanor said.

Dinah nodded once. “Maybe just the trying was the something.”

Years passed. The country strained at its seams. Slavery became a louder argument and a deeper wound. Charles grew increasingly paranoid, granting Thaddeus Cole more authority, more freedom to terrorize. Punishments worsened. Fear became the estate’s heartbeat.

Eleanor watched, helpless and complicit, and hated herself for every breath drawn in comfort. The question that haunted her was not what do I feel, but what do I do with it.

In 1852, she began documenting everything. Names. Families. Sales. Whippings. Cole’s atrocities. Charles’s corruption. She hid pages in places no one would search, behind false panels, inside trunks. She did not yet know what she would do with the record. She only knew someone needed to bear witness.

Mama Seraphine found her in the kitchen garden one day and studied her with eyes that had survived too much to waste words.

“You think paper going to save anybody?” Seraphine asked.

“I think someone needs to write it down,” Eleanor replied. “So it can’t be erased.”

Seraphine’s mouth tightened. “My grandbaby,” she said softly. “Sold last year. Her name Ruth. Twelve years old. Could sing like heaven. You write that down.”

Eleanor nodded, throat tight. “I will.”

Word spread quietly. Enslaved people began slipping their stories to Eleanor as if placing fragile objects in her hands. They wanted names remembered. They wanted losses witnessed. The association was dangerous, but so was being forgotten.

Then, in spring of 1853, a letter arrived through channels that did not exist on any official map. A traveling peddler slipped it to Dinah. Dinah brought it to Eleanor with shaking hands.

Eleanor recognized the handwriting before she finished the first line.

Eleanor, I’m alive. I made it North… I’m in Canada now. I’m free.

The room blurred. Eleanor read it again. Then again. Relief hit like a wave, joy laced with grief for years stolen. Elijah wrote of learning to read openly, of carpentry work, of waking each morning and remembering no one owned him. He wrote of thinking of her every day, not asking her to come, only wanting her to know the risk had not ended in nothing.

Eleanor pressed the letter to her chest as if it could keep her heart from breaking out of her ribs.

She found Dinah. “I need your help,” she said, voice shaking. “I need to go North.”

Dinah did not look shocked. She looked almost relieved. “Been wondering when you was going to decide,” she said. “Choose between dying here or living somewhere else.”

“I have no money,” Eleanor whispered.

Dinah’s eyes flicked toward Eleanor’s jewelry box. “You got jewels. You got things you can sell. And you got me. I know people who know people.”

“The Underground Railroad?” Eleanor asked, the words tasting dangerous.

Dinah nodded slightly. “Not official, but close enough. And if you serious, I can get you connected.”

“What about you?” Eleanor asked. “If Charles learns you helped…”

Dinah’s expression went flat. “He’ll try to kill me whether I help you or not. I’m Black in Louisiana. That’s already a death sentence with flexible timing.”

Eleanor felt hope stir, the small brave animal inside her waking.

They planned in secret. Eleanor sold jewelry piece by piece. She gathered plain clothes. She prepared to take her documentation, the evidence she had risked years compiling. She wrote back to Elijah through the same network, a letter that finally used the word she had avoided.

Wait for me.

The letter left in August 1853.

In September, Charles discovered her records.

He did not confront her immediately. He planned, as he always planned. On October 15th, 1853, his plan caught fire.

The flames began after midnight in a storage room in the east wing, where draperies and old furniture waited like tinder. By the time servants realized, fire was already running through corridors as if the house itself had become a torch.

Eleanor woke to smoke and shouting. She ran to her door and found it locked from the outside. Panic flooded her, thick as the smoke seeping under the threshold.

Charles had locked her in to burn.

She pounded the door until her fists hurt, screamed until her throat burned, then forced herself to think. The window. She ripped back curtains and found it fastened shut. She grabbed a heavy candlestick and began smashing glass. Shards fell two stories to the ground in glittering rain.

She was clearing the frame when the door crashed open.

Dinah stood there, face streaked with soot, eyes wild. Mama Seraphine and two other women crowded behind her.

“Move!” Dinah shouted. “No time!”

They ran through hallways filling with smoke. Heat pressed down like punishment. Somewhere above them, timber groaned. They reached the main staircase just as the chandelier crashed down, crystal exploding across marble like deadly hail.

They burst out onto the lawn into chaos, servants shouting, water buckets passing, enslaved people fighting fire for a house that had never protected them. Eleanor scanned the crowd and realized something unsettling.

Charles was nowhere.

“Where’s the governor?” she shouted over the roar.

Dinah spat on the ground. “Ain’t seen him.”

Eleanor felt certainty snap into place. “He’s inside,” she said. “Something went wrong. He’s trapped.”

Dinah’s face held no mercy. “Good. Let him burn.”

Eleanor understood Dinah’s coldness. Everyone there had earned the right to feel nothing. Still, Eleanor found she could not stand and watch a human being burn alive, even a human being who had tried to murder her. Hatred did not erase her own need to remain someone who could look herself in the mirror.

“I have to try,” Eleanor said, already moving.

Dinah grabbed her arm. “You crazy.”

“Maybe,” Eleanor said, and ran back into the house.

Inside was hell made visible. Smoke erased distance. Flames climbed walls like hungry things. Eleanor covered her mouth with her robe and pushed forward, calling his name.

She found Charles in his study, pinned under a fallen beam, face gray with pain. The room was filling with smoke, and fire licked at shelves of papers that had built his empire.

When he saw Eleanor, surprise crossed his face like a shadow.

“You,” he rasped. “You came back.”

“I’m an idiot,” Eleanor said, grabbing the beam, testing it. It did not move.

Charles coughed, blood appearing at the corner of his mouth. “Your records,” he gasped. “If you take them North… everything I built…”

“So you decided to murder me,” Eleanor said, straining against the beam again. “You could’ve let me go. You would’ve been rid of me.”

“You forced my hand,” Charles whispered. “Since the day you looked at that slave like he was human.”

Eleanor’s laugh came out sharp and broken. “He was human. That was never the question. The question was whether you could survive acknowledging it.”

The floor trembled. The house groaned.

“Go,” Charles said, voice suddenly urgent, frightened. “You can’t save me.”

“I know,” Eleanor said, hands still on the beam. “But I have to try. Not for you. For me.”

Charles’s breath rattled. His eyes flicked toward the spreading flames. “Idealistic,” he muttered, then softer, “that was always your problem.”

“No,” Eleanor replied. “My problem was marrying you at seventeen.”

Another cough, more blood. He stared at her as if seeing her for the first time as a person rather than a possession.

“I don’t want you to die,” he said, words dragging themselves out. “Not really. I was angry.” His voice thinned. “I’m sorry. For what I did to you… to him… to all of it. Live.”

It was the first apology of their fifteen-year marriage, and it was useless, and yet it landed in Eleanor like a stone dropped into water, rippling through her in ways she did not have time to understand.

“I know,” she said, and meant only that she heard him.

Then Dinah and Seraphine appeared through the smoke, grabbing Eleanor’s arms.

“No!” Eleanor fought. “We have to get him out!”

Seraphine’s voice was blunt as truth. “That beam crushed something inside him. He dead anyway. We ain’t dying with him.”

They dragged Eleanor out. She resisted until they threw her onto the lawn. The moment she hit the ground, the center of the house collapsed inward with a sound like the world ending.

Charles Bowmont died inside the ruin he had built on human misery. By dawn, there was nothing left but smoking beams and ash.

Eleanor sat on the grass beside Dinah, both of them silent, watching people move through shock, trying to count losses and possibilities.

“My records,” Eleanor whispered finally. “They’re gone.”

Dinah looked at her. “People still here,” she said. “Stories still here.”

Eleanor swallowed the grief and felt something harden into resolve.

“I’m still going North,” she said. “And I’m taking anyone who wants to come.”

Dinah’s eyebrows lifted. “You serious?”

“Completely,” Eleanor said. “Charles’s brother will take weeks to arrive. This place will be chaos until then. That’s our window.”

Over the next three weeks, Eleanor used what remained of her jewelry and the confusion of transition to orchestrate the largest escape St. Helena Parish had ever seen. Seventeen people left in wagons with false floors, on foot through swamps, by night along routes whispered like prayers. Some would make it to Canada. Some would find freedom in Northern states. Some would be caught. Every one of them would have chosen risk over certainty.

On a cold morning in November, Eleanor and Dinah left as well, slipping out as Charles’s brother arrived to claim the damaged inheritance of the Bowmont name.

Their journey north was not romantic. It was mud, hunger, fear, and endless movement. Safe houses that felt like miracles. Kind strangers who risked their own lives. Nights spent listening for dogs. Days spent hiding beneath boards, breath held, muscles cramping, hope held like a fragile thing against the chest.

Four months later, they reached Canada.

Eleanor found Elijah in a small town outside Toronto, building a fence with hands that belonged to him now. His face was fuller than she remembered. His eyes carried less grief, more steadiness, as if peace was finally something he could touch.

When she appeared at his door in March of 1854, he stared at her as if she were a ghost.

“I told you I was coming,” Eleanor said, and then she was in his arms, both of them crying with the fierce relief of people who had crossed fire to reach each other.

They did not pretend the past had been clean. They did not pretend their love had been uncomplicated. They spoke of guilt and harm and the long shadow of what had been done to Elijah long before Eleanor ever saw him. They spoke of the people left behind, of the ones who had not made it. They allowed love to be not a rescue story, but a choice made in full awareness of the world’s ugliness.

Three weeks later, they married quietly. The small free Black community that had taken Elijah in did not all approve, but they watched Eleanor work, watched her insist on humility rather than entitlement, watched her spend her resources helping newly arrived escapees find rooms, work, food. Trust came slowly, as it should.

Dinah found work as a seamstress, then married a formerly enslaved man from Kentucky, and spent the rest of her life helping new arrivals learn how to live without chains even after chains had shaped their minds. She laughed more in Canada than she ever had in Louisiana, though some nights she still woke from dreams of dogs and torches.

Eleanor never returned South. She lived in Canada with Elijah for decades, raising children who grew up free and educated, who never learned to flinch at the sound of boots. Under a pseudonym, she wrote accounts of slavery from the perspective of someone who had benefited from it and then refused to keep benefiting. Her words traveled into abolitionist circles like sparks.

Elijah built houses and tables and cradles, objects meant to last, objects that proved his hands were made for creation, not only survival. He spoke sometimes of Grace, the daughter he had lost, and Eleanor listened, not trying to fix grief, only honoring it.

Together, they planted a memorial garden. A magnolia tree for every person they had known who had died enslaved, for every name Eleanor had once written down and lost to fire, for every story that deserved to exist outside whispers. The trees grew tall, roots threading into Canadian earth, blossoms opening each summer as if insisting that beauty could be an act of defiance.

In Louisiana, people told a different legend. They called the ruins of the Bowmont mansion a warning about pride and scandal and knowing one’s place. They spoke of fire as punishment, of the governor as tragic, of the wife as unstable.

Those who knew the truth carried a different meaning. They understood that the ruins were not simply the end of a dynasty, but the collapse of a lie. A lie that said some people were born to own and others were born to be owned. A lie that said love could be legislated into obedience, that dignity could be whipped out of a body, that humanity could be divided by skin.

Eleanor lived long enough to become an old woman with silver hair who still walked the garden each morning, touching leaves as if counting names. Elijah outlived her by four years, tending magnolias like he was tending memory itself. When he died, their children and grandchildren kept planting.

Some victories are loud, recorded in speeches and battles. Others are quieter, built from stubborn decisions made in the dark: to see someone the world insists is invisible, to tell the truth even when truth is dangerous, to choose a life that does not require another person’s suffering as payment.

The Bowmont mansion burned. The system that fed it fought to survive. Yet two people, trapped on opposite sides of a cruelty dressed as law, reached across and refused to pretend the other was less than human.

And that refusal, carried forward like a lantern through generations, was its own kind of freedom.

News

The MILLIONAIRE’S BABY KICKED and PUNCHED every nanny… but KISSED the BLACK CLEANER

Evan’s gaze flicked to me, a small, tired question. I swallowed once, then spoke. “Give me sixty minutes,” I said….

Can I hug you… said the homeless boy to the crying millionaire what happened next shocking

At 2:00 p.m., his board voted him out, not with anger, but with the clean efficiency of people who had…

The first thing you learn in a family that has always been “fine” is how to speak without saying anything at all.

When my grandmother’s nights got worse, when she woke confused and frightened and needed someone to help her to the…

I inherited ten million in silence. He abandoned me during childbirth and laughed at my failure. The very next day, his new wife bowed her head when she learned I owned the company.

Claire didn’t need to hear a name to understand the shape of betrayal. She had seen it in Daniel’s phone…

The billionaire dismissed the nanny without explanation—until his daughter spoke up and revealed a truth that left him stunned…..

Laura’s throat tightened, but she kept her voice level. “May I ask why?” she said, because even dignity deserved an…

The Nightlight in the Tunnel – Patrick O’Brien

Patrick walked with his friend Marek, a Polish immigrant who spoke English in chunks but laughed like a full sentence….

End of content

No more pages to load