St. Jerome Plantation stretched across the Louisiana lowlands like a kingdom that didn’t need a crown to feel sovereign. In late summer the air sat heavy, sweet with crushed cane and damp earth, and the mosquitoes behaved like tiny creditors: relentless, confident they’d be paid in blood. From the levee road, travelers saw only the orderly geometry, the rows of sugarcane laid out in obedient lines, the white fences and the live oaks draped in moss that looked like old lace. But anyone who stayed long enough learned the deeper design. The big house stood on a mild rise, elevated like a judge’s bench, its tall windows always watching down, always reminding the world who issued orders and who absorbed them.

Colonel Rutherford Clay owned that view and everything that fed it: the land, the mill, the cattle, the fields, and the people he spoke of as “hands” as if a whole human life could be reduced to a tool. He was a thick-bodied man with a heavy mustache and a laugh that carried the easy certainty of someone who had never been told no and lived long enough to believe that meant the universe agreed with him. His sons, Hart and Deacon, rode like they were born in the saddle and talked of expansion the way other men talked of weather. They were already promised to daughters of neighboring planters, alliances sealed with smiles and silverware and the quiet arithmetic of inherited acres.

And then there was his daughter.

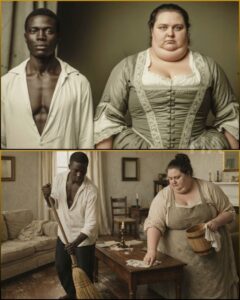

Adeline Clay was twenty-two and, by the unkind measures of her household, a scandal no one wanted to admit existed. She was large, yes, larger than any dressmaker in town wanted to account for, heavier than any parlor visitor expected to see moving through a doorway. But it wasn’t gluttony that built her body; it was loneliness that built her habits. In a house where every glance could turn into a verdict, food had become the one thing allowed to her without immediate argument. A biscuit meant ten minutes in which nobody commented on her shape. A spoonful of preserved peaches meant a brief ceasefire. Her mother, Clarissa Clay, did not offer comfort, exactly. She offered silence, which sometimes felt like mercy when compared to the sharper alternatives.

Adeline lived in the third room off the left corridor, the one with curtains so thick the daylight had to beg to enter. The windows stayed shut, not because she preferred darkness, but because her father had decided long ago that the world did not need to look at her. Visitors didn’t ask, and the household didn’t answer. The absence became a habit, and habit became policy. Adeline learned to read in secret, borrowing books passed hand to hand by a cook who couldn’t risk being caught teaching the planter’s daughter anything that might give her ideas. She stitched and unstitched the same embroidery patterns because no one taught her properly, and because doing something with her hands was better than waiting with them folded.

She waited anyway, though she could not have named what for. Not rescue. Not romance. Those were stories for other girls, the ones whose laughter belonged to the public rooms. Adeline waited for a moment when her life might feel like it was hers.

That moment arrived on an August morning with the sound of boots on stairs.

Colonel Clay’s steps had a vocabulary. There was his casual walk, the one used for leisure. There was his drunk walk, after dinners that lasted too long and left the air smelling of cigar smoke and bourbon. And then there was the walk that meant he had made a decision and intended to announce it like a sentence.

Adeline recognized it the way a sailor recognizes a change in wind.

The door opened without a knock. It never knocked for her.

“Get up,” Colonel Clay said, no greeting, no softening.

Adeline had been sitting in her chair near the shuttered window, a book gone slack in her lap. She rose slowly, as if she could stretch time into mercy. Her knees ached the way they always did, joints tired of carrying a body that was treated like evidence of a moral crime. She wore a gray dress, loose and plain, the kind of garment meant to hide rather than adorn. Her mother often said there was no sense wasting good fabric on someone who wasn’t going to be seen.

Colonel Clay stood in the threshold, arms crossed, looking at her with the same impatience he reserved for livestock that wasn’t doing what it was bred to do.

“I found a solution,” he said.

Adeline didn’t answer. She had learned, over years, that words could become kindling in the wrong hands.

“No decent man will have you,” he continued, voice steady with the comfort of his own cruelty. “That’s a fact. I tried three times to arrange a match. Three. And every one of them backed out the moment they laid eyes on you.”

His words were not new. What was new was the calm satisfaction in his face, as if he’d solved a nuisance with the same ease he might solve a broken hinge.

“So I’ve decided. I’m giving you to Old Ben.”

The room tilted. The air seemed to thicken, as if the humidity had crept indoors to listen.

Adeline gripped the chair back to steady herself. “Old Ben” was what the household called Benjamin Hale, an enslaved man who had lived on St. Jerome longer than some of the oak trees had been tall. He was in his sixties, bent from decades of cane cutting and mill work, hands knotted and scarred. The overseer assigned him lighter tasks now, not out of compassion, but because a body that old was a poor investment for heavy labor. Ben lived in the farther row of cabins, where the elders stayed when their strength began to fail and their value, in the planter’s eyes, declined.

“You can at least be useful,” Colonel Clay said. “He needs a woman. You need… purpose. It’s settled.”

Adeline’s mouth opened and closed once, like a fish brought too suddenly to air. She found her voice only because panic hunted it out of her throat.

“Father… I can’t. I don’t want—”

“I didn’t ask what you want.” His tone snapped like a whip without needing one. “Tomorrow morning you come downstairs, take what belongs to you, and you go live in his cabin. You’ll cook. You’ll clean. You’ll do what a woman does. Maybe you’ll finally earn your keep.”

He turned and left the door open behind him, as if even the act of closing it was beneath him. Adeline remained standing, staring at the strip of hallway visible through the gap, listening to his boots retreat. When the house returned to its usual quiet, it did not feel like peace. It felt like a predator settling after the pounce.

That night, Adeline didn’t sleep. She sat in her dark room and listened to the plantation breathing: distant voices from the quarters, dogs barking at shadows, the mill’s low groan as it cooled, the wind worrying the trees. Underneath all of it lay the heavy silence of a life she had never been allowed to steer.

Down at the cabins, Ben learned of Colonel Clay’s decision the way enslaved people learned most things: through an announcement performed like entertainment. The overseer, Mr. Pruitt, walked the row at dusk and called it out loud enough for everyone to hear.

“Old Ben’s getting himself a bride,” Pruitt said, grinning. “The colonel’s own daughter. Ain’t that a prize?”

Laughter broke out, quick and sharp, because laughter was sometimes the only safe way to swallow bitterness. People laughed because they knew what this was: humiliation set on a platter for two.

Ben did not laugh.

He stared at the dirt floor near his boots, at the calluses and scars and the crookedness time had carved into his hands. He felt rage, not at the girl he’d barely seen, but at the man who believed he could move lives around like pieces on a board. Ben had been brought to Louisiana as a boy, sold from a trader’s wagon, his earliest memories a blur of heat and chains and someone’s voice singing in a language he no longer understood. Fifty years on this land had taught him the rules of survival, but they had not taught him to accept being used as a weapon to punish someone else.

When Adeline walked down the big house stairs the next morning, she did it as if each step might be her last chance to turn back. She carried a small bundle: three dresses, a hairbrush, and the book she’d been reading when her father came into her room. No one came to say goodbye. Her mother stayed upstairs. Her brothers were already out riding. The house seemed relieved to be rid of her, like a room exhaling after holding smoke too long.

In the kitchen, an older woman named Celeste pressed a wrapped parcel into Adeline’s hands. Celeste’s eyes were careful, her movements practiced in quiet generosity.

“It’s bread and cane jam,” she whispered. “It ain’t much, but it’s what I can give.”

Adeline swallowed around the ache in her throat and nodded. “Thank you,” she managed, the words small but real.

The walk to Ben’s cabin took ten minutes. Ten minutes across a yard that felt suddenly enormous, as if distance itself were conspiring to make her shame public. She passed workers hauling water, women carrying laundry, men moving tools, all of them pausing to look. Some faces held curiosity. Some held judgment. A few held something softer, like pity that didn’t know where to rest.

The sun pressed on her shoulders. Her boots pinched. Sweat gathered at her collar. But what weighed most was the knowledge that her father had turned her into a transaction, and that she was being delivered like an object.

Ben was sitting on the cabin’s worn threshold when she arrived. He rose slowly, joints complaining, and looked at her without lust, without ridicule, without the quick appraisal she was used to. His gaze was steady, measuring in a different way, as if he was trying to see the person inside the story that had been told about her.

“You can come in,” he said.

His voice was rough with age and labor, but there was no cruelty in it. Just fact.

Adeline stepped inside. The cabin was a single room, tight and plain: dirt floor, walls of rough boards, a small table with two stools, a pot hung on a hook, a thin pallet of straw in the corner. A narrow window let in a strip of light. The place smelled of smoke, sweat, and time. It was not home. But it was not the big house either, and that difference landed in her like a strange kind of possibility.

Ben closed the door behind her. The sound made Adeline’s heart jump, reflexive fear rising like a wave. She held her breath.

Ben did not move toward her. Instead he walked to the table and sat heavily, elbows on his knees.

“Sit,” he said, nodding at the other stool.

Adeline sat with her hands clenched in her lap, unsure what to do with her body, with her face, with the fact of her own existence in a place she’d never been allowed to imagine herself.

For a long moment, neither of them spoke. The silence stretched, not sharp but careful, as if both were listening for the safest way to be human.

Finally Ben said, “I didn’t ask for this.”

Adeline’s eyes lifted to him.

“I didn’t want you brought here like a sack of feed,” he went on. “I don’t want you thinking I had a hand in it. That man… he uses folks. He used you, and he meant to use me too.”

Adeline’s throat tightened. She managed, “I didn’t want it either.”

Ben’s mouth twitched into something like a humorless smile. “Seems we got that in common.”

She looked at him properly then, really looked. The deep lines in his face were like old riverbeds carved by hardship. His eyes were tired but alert, as if they had witnessed horrors and still refused to close. The dignity in him wasn’t loud. It was stubborn.

“I’m scared,” Adeline admitted, the honesty surprising her.

Ben nodded once, slow. “You ought to be. This place gives folks reasons.” He held her gaze. “But here’s what I can tell you. I won’t lay a hand on you. Not like that. Not ever, unless you wanted it, and I don’t reckon you do.”

Adeline blinked hard. Tears threatened, not from sadness alone, but from the shock of being offered a choice, even a small one.

Ben added, softer, “We’ll make this… something we can live through.”

Those words did not solve anything. But they built a plank across a chasm.

The first days were awkward in a way that made Adeline feel like she was walking in a room full of glass. Ben rose before dawn and did the work he was given: mending fence, tending chickens, carrying water, tasks meant to squeeze usefulness out of an aging body. Adeline stayed near the cabin, learning how to cook with rationed supplies, how to wash clothes in cold water, how to patch holes in fabric with thread that snapped too easily.

At night they shared the same pallet because there was only one, but Ben arranged a folded blanket between them like a boundary drawn in kindness. Adeline lay awake listening to the sounds of the quarters, listening to Ben’s breathing, astonished by the fact that she could exist beside a man and not feel hunted.

People did mock them at first. Men snickered when Adeline passed. Women whispered behind hands. The overseer made crude jokes within earshot, pleased with his own cruelty. Adeline expected those voices to bury her.

But Ben carried an authority that decades hadn’t stripped away. He didn’t threaten violence; he didn’t need to. His gaze alone could quiet a room. He had a way of speaking that made even the younger men pause, not out of fear of punishment, but out of respect that had been earned in a world where respect was rare.

One evening, after a day when the heat felt like a wet blanket thrown over the land, Adeline surprised herself by laughing.

It was small, just a breath of sound at something Ben said about the plantation’s endless obsession with appearances. “They paint the big house white,” Ben murmured as they ate beans and cornmeal, “like paint can hide what’s underneath.”

Adeline covered her mouth, but the laugh escaped anyway. Ben watched her with something like wonder.

“Haven’t heard that sound from you before,” he said.

“I haven’t made it in a long time,” Adeline admitted.

Their conversations started with practical things, then slowly deepened. Ben told stories, careful ones, about people he’d known, about families torn apart and small rebellions that had lived only in whispered plans. He didn’t tell those stories to frighten her. He told them because truth mattered, and because Adeline, unlike most people in the big house, listened as if his words were worth keeping.

Adeline spoke about books, about places she’d read of but never seen. She described cities with gas lamps and libraries, oceans that smelled like salt and possibility. Ben asked questions, curious in a way that surprised her. He could not read, but his mind was sharp, and his hunger for knowledge made her feel less alone in her own quiet longing.

One night, when rain hammered the roof hard enough to make the cabin leak, Adeline realized something that startled her more than any cruelty had.

She felt… safe.

Not safe in the grand sense. The plantation was still what it was: a machine built to grind people down. But inside this small cabin, in the company of a man who refused to treat her like an object, she found a pocket of peace that made her chest ache with gratitude.

And because the plantation could not bear the existence of peace it hadn’t granted, Colonel Clay noticed.

He saw Adeline crossing the yard without the hunched posture of defeat he’d expected. He saw Ben working with something like steadiness in his shoulders. The colonel had given away what he considered a disgrace and expected it to disappear. Instead it had become visible again, not as spectacle, but as life.

That offended him.

One afternoon he came down to the quarters with the overseer and his two sons in tow. They approached like a storm line, deliberate and loud. Adeline was outside washing clothes in a tin basin. Ben was on the roof patching a leak.

Adeline’s hands froze in the suds when she saw them.

Ben climbed down slowly, placing himself between Adeline and the men without bravado, simply as if his body understood its duty before his mind could argue.

“Well, I’ll be damned,” Colonel Clay said, voice pitched for an audience. “So it’s true. You two settled in real comfortable. Almost like real folks, living a real little life.”

Ben kept his gaze level. “We’re doing what you told us to do, Colonel.”

Clay’s laugh was sour. “Doing what I told you, yes. But I didn’t tell you to be content.” His eyes slid to Adeline like she was something unpleasant stuck to a boot. “Contentment ain’t for people who don’t earn it.”

Adeline felt the old fear rise, the familiar nausea of being near her father’s anger. Her instinct screamed at her to shrink, to apologize, to make herself smaller than she already felt.

Then Ben’s hand found hers, rough palm briefly squeezing her fingers. Not romance. Not claim. Just a message: You are not alone.

“What do you want?” Ben asked, voice calm but edged with something hard.

“I want to remind you of your place,” Colonel Clay said. “Ben, you go back to the fields. Full work. None of this light duty. And you,” he nodded at Adeline, “you come back to the big house. I’ll find a convent willing to take you. Better you rot praying than keep… infecting my property with this farce.”

The words hit Adeline like cold water. She imagined herself returned to her dark room, the curtains drawn, the world once again reduced to a narrow slice of light she wasn’t allowed to touch.

Something inside her, something that had been starved so long it barely knew it was alive, rose up like a sudden flame.

“No.”

The word fell clear in the humid air.

Silence snapped tight. Even the birds seemed to pause.

Colonel Clay stared at her as if he’d never seen her speak before. “What did you say?”

Adeline’s heart pounded so hard she could feel it in her throat, but she did not back away. “I said no. You gave me to him by your own rules. You treated me like property and handed me over like property. If you want to keep pretending this world is built on ownership, then understand what that means. You can’t take it back just because you’re angry.”

It was an argument born of desperation and clarity. Colonel Clay worshiped property. He had used that logic to justify his power. Adeline was throwing it back at him like a mirror.

Clay’s face flushed red. He stepped forward.

Ben moved fully in front of Adeline, steady as a door closing. “You can work me to death if you want,” he said. “You can put me in the cane till my back breaks for good. But if you drag her back after what you done, everyone here will know your word ain’t worth spit.”

The insult wasn’t the language. It was the idea.

Colonel Clay lived on reputation as much as he lived on land. His authority depended on fear, yes, but also on the belief that his decisions were final. If he reversed himself publicly, he would show weakness. Weakness invited questions, and questions were the first crack in any tyranny.

For a long moment, he stood caught between pride and rage, trapped by his own need to appear unbreakable. Finally he spat into the dirt, turned, and walked away without another word. His sons followed, their faces hard with confusion, the overseer trailing like a dog unsure whether it had been called off or merely delayed.

Adeline and Ben remained where they were, their hands still linked, both shaking with adrenaline. When the group vanished beyond the trees, Ben exhaled a long, trembling breath.

“That’ll have consequences,” he said quietly.

“I know,” Adeline whispered.

But she was smiling, not because she believed the danger was gone, but because for the first time in her life she had chosen something. She had stood in front of the man who had spent decades shrinking her and refused to fold.

The consequences came, but not in the shape of immediate separation. Colonel Clay didn’t dare undo the arrangement publicly. Instead he punished them in ways he could pretend were ordinary. Their rations were cut. Ben was assigned harder labor. The overseer lingered near their cabin, looking for reasons to strike.

Hunger entered their days like an unwelcome guest who refused to leave.

Yet something else entered too: attention.

People watched Ben and Adeline differently now. Not with pity. Not with mockery. With a cautious kind of respect, like they had witnessed a candle survive a gust and were unsure whether to believe it. In a world built on the lie that no one had choices, seeing someone say no made the lie wobble.

Adeline’s body changed under the new life. Not because she was punished into transformation, but because she was moving, working, living. Her hands toughened. Her shoulders strengthened. She learned to plant small kitchen plots near the cabin, learned which weeds could be boiled into something that tasted almost like nourishment. Ben taught her how to read the sky for rain, how to listen to the frogs and know when the river would rise, how to find herbs that eased pain and lowered fever.

In return, Adeline taught Ben letters.

At first she used a stick in the dirt, drawing shapes that meant nothing to him. He stared as if she was performing magic.

“That one,” she said, tracing carefully, “is A.”

Ben tried to copy it. His hand shook. The line came out crooked.

“Still an A,” Adeline said. “It counts.”

He gave her a look that held both gratitude and grief. “Ain’t nobody ever thought I was worth counting.”

“You are,” Adeline said simply, and the simplicity made it true.

Time moved, as time always does, indifferent to fairness. Seasons turned. The cane grew, was cut, grew again. Ben’s body deteriorated, the hard labor claiming what decades had already borrowed. Some nights he coughed until Adeline feared his lungs would give out. She sat with him, holding water to his lips, pressing warm cloths to his forehead, using every scrap of knowledge he’d taught her to keep him breathing.

The plantation remained brutal. People were still bought and sold. Families were still threatened. Violence still waited like a tool hung on a wall. Adeline never forgot that her own suffering existed inside a larger machine that crushed so many others more completely. She did not romanticize her cabin. She did not pretend kindness erased chains.

But inside that narrow room, she and Ben kept building something stubborn: a life measured not by ownership, but by seeing and being seen.

Years later, when war finally tore the country open, the plantation trembled with rumors and fear. Men spoke in whispers of Lincoln and soldiers and freedom. Some of the younger enslaved men slipped away at night, following the North Star with hope sharpened into desperation. Others stayed, trapped by families, by age, by the sheer risk of being caught.

Ben lived long enough to hear the word “emancipation” spoken aloud like a prayer.

He died not in the fields, but in the cabin, on a winter morning when frost painted the yard white and the air tasted clean for the first time in months. Adeline sat beside him, holding his hand, feeling the pulse slow like a fading drum.

“You did good,” Ben whispered, voice thin.

“No,” Adeline said, tears sliding down her face without drama, without shame. “We did.”

Ben’s mouth curved slightly. “That’s right.”

When he was gone, Adeline stayed with his body for hours, not because she didn’t know what to do, but because she needed the world to understand what it had taken from her and what it had given back. She did not wail. She did not perform grief for anyone else’s comfort. She simply held his hand and thanked him in silence for treating her as human when her own household had refused.

Colonel Clay did not live to see the war’s end. His heart gave out in a year of shortages and fear, and his sons inherited a land whose old certainty was cracking. Hart became the new master, and though he was less theatrical than his father, he was still shaped by the same worldview, still struggling to accept a country that no longer validated him so easily.

When freedom became law, it did not arrive like a clean sunrise. It arrived like a door unlocked in a house still full of people who didn’t want you walking out. The structures remained. The land remained in the same hands. Poverty waited like a trap outside the gate.

Adeline, now older, now changed by work and loss and stubborn survival, did not leave St. Jerome.

Not because she didn’t want to. Not because she believed the plantation deserved her loyalty. But because freedom, for her, had become less about location and more about what she chose to do with her days.

She stayed in the cabin. She planted herbs Ben had shown her. She taught children to read, sitting them on overturned crates, tracing letters in the dirt the same way she had traced them for Ben. She taught them their names mattered. Their words mattered. Their lives could not be reduced to “hands.”

One afternoon, long after the war, a young girl asked her a question that held the blunt curiosity of the unbroken.

“Miss Adeline,” the girl said, brow furrowed, “why didn’t you go somewhere else when you could?”

Adeline looked toward the fields, the rows still stretching like old habits, and felt the complicated weight of memory settle in her chest. She thought of the big house on the hill, the curtains drawn, the way her father had tried to erase her. She thought of Ben’s hand squeezing hers, steady and real. She thought of the first time she had said no and felt the world pause, shocked that she existed loudly.

“Because I learned something here,” Adeline said.

The girl waited.

Adeline continued, voice quiet but firm. “I learned you don’t have to run to be free inside yourself. Sometimes freedom is looking somebody in the eye and saying no when they expect you to crumble. Sometimes it’s planting something where nobody thinks anything good can grow. Sometimes it’s refusing to break on the inside even when everything outside is designed to crack you.”

The girl frowned, not fully understanding, but storing the words the way children store seeds.

Adeline reached up and touched the cabin’s doorframe, where two names were scratched into the wood, old and careful: BEN and ADELINE. Not as property marks. A witness.

“He taught me that,” Adeline said softly. “Not with pretty speeches. With every day he woke up and chose to stay human in a place that tried to make him into a thing. And when he did that for himself, he did it for me too.”

The girl stared at Adeline as if she’d been handed a riddle instead of an answer. Her eyes flicked from Adeline’s weathered face to the cane rows in the distance, then back to the cabin again, as though she expected freedom to be hiding somewhere visible, perched on the fence rail like a bird. Behind them, late afternoon light fell honey-thick across the yard, catching on dust motes and the soft green of young weeds pushing up where the ground had been trampled for decades. The plantation, even in its “after,” still moved like an animal that didn’t realize it had been wounded: the mill creaked, men hauled sacks, women carried water, and the old habits of power tried to pretend they were just the natural order of things.

“You mean…” the girl began, then stopped, embarrassed by her own uncertainty. “You mean you can be free even if you still… stay?”

Adeline studied her a moment, weighing how much truth a child could carry without it turning to stone in her hands. She had learned, over the years, that the world loved simple stories. The world loved a clean ending: chains broken, villains punished, sunrise applause. But St. Jerome had never been a place that respected clean lines. It was a place that fed on mess, on compromise, on people learning to swallow grief like medicine because it was the only way to keep going.

“I mean,” Adeline said gently, “that freedom starts where nobody else can reach to steal it. And then, if you can, you build the rest from there. One board. One lesson. One day.”

The girl chewed her lip, then nodded as if saving the sentence in a pocket she didn’t fully understand yet. She glanced again at the doorframe and the scratched names, and her voice dropped, reverent without knowing why. “Did he write them?”

Adeline’s fingers lifted to the wood, stopping just shy of touching it as if her skin could still feel Ben’s steady presence in the grain. “He did,” she said. “Not at first. At first he didn’t even believe a letter could belong to him. But once he learned… once he understood that marks could become meaning… he wanted proof that he’d been here as himself. Not as somebody’s property. Not as a joke for men to repeat. Himself.”

The girl’s face tightened with a child’s instinctive anger at injustice. “My daddy says the old master men want us to forget.”

Adeline’s mouth curved, not in amusement, but in recognition. “They do. Forgetting is cheaper than paying what’s owed. But you listen to me.” Her voice firmed, the way it did when she taught. “Words are how you refuse. Words are how you remember. And if you can read them, nobody can put lies in your mouth and call them truth.”

The next morning, she gathered the children again, not just the girl who had asked, but the others too, barefoot and watchful, their bodies still learning what it meant to stand without flinching. She found a broken plank and set it over two stumps like a table, then took the stick she’d once used with Ben and drew letters in the dirt. The air smelled of damp soil and cane sweetness and something faintly metallic from the old iron tools nearby. She wrote slow, patient strokes as if she were laying down a road.

“This,” she said, tracing the first shape, “is A.”

A little boy squinted and whispered, “Like your name.”

“Yes,” Adeline replied, and felt the quiet thrill of that connection. “Like my name. Like a beginning.”

They repeated the letter until it stopped looking like a strange symbol and started looking like a key. They said it out loud until their tongues stopped stumbling over it. It wasn’t magic, exactly. It was steadier than magic. It was work.

And work, Adeline had learned, could be used to crush you, or it could be used to build.

News of her lessons drifted the way smoke did, curling into places it wasn’t invited. Within a week, Hart Clay heard about it, not from kindness but from irritation. His father’s death had left him an inheritance that felt less like a throne and more like a burden balanced on a cracked beam. He could still call himself “master” if he wanted, and plenty of men nearby still did, but the law had changed, and the world had developed teeth where it used to have none. Union patrols had ridden through once and twice. A Freedmen’s Bureau agent had stopped at the big house and spoken with the kind of cool authority that made Hart’s jaw tighten. Hart didn’t like being told what he could not do. He liked it even less when the person doing the telling wore the same skin tone as he did.

So when his overseer, Pruitt, came up the steps one evening with a sour look and said, “That woman down in the old cabin is gathering folks. Teaching them. Like it’s a schoolhouse,” Hart’s first reaction wasn’t fear.

It was offense.

“A schoolhouse,” Hart repeated, rolling the word around as if it tasted wrong. “Down there.”

“Yes, sir. Kids. Some grown ones too. They’re coming after dark.”

Hart’s gaze moved toward the window, down the long slope of the yard, past the cane, toward the quarters that no longer belonged to him in the same unquestioned way. He could still punish, in a hundred small, legal-looking ways. He could still starve someone out with wages withheld. He could still “evict” a family that had nowhere else to go and call it business. The system had changed costumes, but the bones were familiar.

And that was what made the idea of Adeline teaching intolerable. Not because learning itself threatened him. Hart had learned plenty. It was because her learning had never been meant to exist at all. She was supposed to remain a hidden embarrassment, a closed-curtain secret. Instead she had become something visible, something with gravity, something that made people gather around her without permission.

He felt the old plantation instinct rise: correct the disorder. Reassert the story.

“Bring her up here,” Hart said.

Pruitt hesitated. “Sir… folks talk.”

Hart’s eyes snapped. “I said bring her.”

When Adeline stepped into the big house again for the first time in years, she felt the old chill sweep through her like a draft under a door. The hallway was the same, polished and bright, smelling faintly of beeswax and old money. The portraits still watched from the walls, stern faces painted into permanence, all of them men who believed they had been chosen by God to own. The windows were still tall, and the height still felt like a message.

Hart waited in his father’s study, leaning against the desk as though trying to look effortless. Deacon stood near the fireplace, arms crossed, watching her with a wary curiosity that wasn’t quite contempt. Their mother, Clarissa, sat stiff-backed in a chair by the window, her face pale and controlled, her hands folded as if holding herself in place. She had not spoken to Adeline properly since the day Adeline left. Silence had been her language, and she’d used it like a lock.

Hart’s voice came out flat. “So you’ve decided to play teacher.”

Adeline met his gaze without lowering her head, and felt a small, private astonishment at how natural that defiance had become. Years ago, this room would have swallowed her. Now it simply existed around her like furniture.

“I teach,” she said. “Yes.”

“And who gave you permission?”

Adeline’s eyes flicked, briefly, to Clarissa. Her mother flinched almost imperceptibly, as if struck by the reminder that permission had always been the family’s weapon. Adeline returned her attention to Hart.

“No one,” she answered. “That’s the point.”

Hart’s mouth tightened. “You’re stirring up trouble.”

“I’m stirring up letters,” Adeline replied, calm as river water. “If trouble comes from that, maybe the trouble was always there.”

Deacon snorted, not quite a laugh. Hart shot him a look, then turned back to Adeline, voice sharpening. “This plantation needs order. People need to work. Not gather around some dirt-yard lesson like they’re in a parlor.”

“They work,” Adeline said. “They’ve always worked. They worked before sunrise and after dark while your father called them ‘hands’ as if the rest of them didn’t count. Don’t pretend the work is what you’re protecting.”

Hart took a step closer, the way his father used to. For a moment Adeline felt the old memory try to climb into her throat like bile. Then she remembered Ben’s hand squeezing hers. She remembered the boundary blanket on the pallet. She remembered the first time she said no and the air changed.

She did not move back.

Clarissa finally spoke, her voice brittle. “Adeline… why are you doing this?”

Adeline looked at her mother, really looked, and saw the cost of a lifetime spent cooperating with cruelty to survive it. Clarissa’s eyes were tired in a way powder could not hide. She had been the planter’s wife, the lady of the house, and she had still been trapped in a role that demanded she be small in different ways.

“Because no one did it for me,” Adeline said quietly. “And because Ben deserved to see it.”

Deacon’s brows furrowed. “Ben.”

“Yes,” Adeline replied. “Benjamin Hale. The man you all called Old Ben like he was a broken tool you couldn’t be bothered to name properly. He learned to write his name before he died. He wrote it like a flag.”

Hart’s expression flickered, just for a breath, with something that might have been discomfort. He covered it quickly with anger. “That has nothing to do with my property.”

Adeline’s gaze sharpened. “It has everything to do with it. Your father’s ‘property’ became people the moment they were allowed to be, and the only reason you want them ignorant is because ignorance is easier to exploit.”

Hart slammed a hand on the desk. “Enough.”

The sound cracked through the room. Clarissa jolted. Deacon’s jaw tightened. Adeline didn’t flinch.

Hart leaned forward, eyes hard. “You stop the lessons. If you don’t, I’ll have Pruitt clear that cabin out. Tear it down if I have to.”

Adeline held his gaze. “Then do it in daylight,” she said. “Do it with witnesses. Do it while the Bureau agent is still within riding distance. Do it while people can see you destroying the one thing that’s keeping the children from being trapped in the same mud you were born into with boots already on your feet.”

Hart’s nostrils flared. “You’d call the Bureau on your own family?”

Adeline’s voice stayed even. “You mean, would I ask for help to stop you from hurting people? Yes.”

The room went still, as if even the curtains were listening. Clarissa’s hands tightened in her lap.

Deacon spoke then, low. “Hart… it ain’t worth that. They’ll make noise. Papers will write. Folks already think we’re barely holding on after the war.”

Hart glared at his brother, then back at Adeline, his pride warring with calculation. Adeline could see the same trap his father had once fallen into, the same narrow space between cruelty and reputation. In that crack, there was leverage.

Finally Hart straightened, jaw working. “Fine,” he snapped. “Teach your letters. But if work slows, if people start getting ideas about refusing orders, I’ll shut it down.”

Adeline nodded once. “They already have ideas,” she said. “The only question is whether you want those ideas to be about building a life… or burning one down.”

Hart’s eyes went cold. “Get out.”

Adeline turned and walked away, her steps steady on the polished floor. As she passed Clarissa, her mother’s voice caught, small as a thread.

“Adeline.”

Adeline paused.

Clarissa’s eyes glistened, but her face held the habit of restraint so tightly it looked painful. “I didn’t know how,” she whispered.

Adeline swallowed, the old grief rising like a tide. She could have said a hundred things. She could have asked why her mother had let the curtains close, why she had chosen silence over defense. But Adeline had spent too many years learning that people made their choices inside cages they didn’t always admit existed.

“You can learn,” Adeline said softly. “If you want.”

She left without waiting for an answer.

That night, when she returned to the cabin, she found people waiting, not just children, but men and women too. Their faces were lined with exhaustion and hope, a combination that made Adeline’s chest ache. Someone had lit a lantern and set it on a crate, its glow trembling in the humid air. The girl from earlier, the one who asked why Adeline stayed, sat in front with her knees pulled up, eyes bright.

Adeline drew letters again. A, B, C. She watched mouths shape sounds. She watched hands, calloused from labor, try to hold charcoal gently enough to form a line. She watched pride bloom in places that had been trained only for submission.

At the end of the lesson, the girl lingered after the others drifted away. “Miss Adeline,” she said, voice low, “my daddy says the master men are scared of books.”

Adeline smiled, tired and real. “They’re not scared of books,” she corrected. “They’re scared of what happens when you realize you can write your own name and it still belongs to you.”

The girl nodded solemnly. Then, like a confession, she whispered, “I want to write mine.”

“What is it?” Adeline asked.

The girl hesitated, then lifted her chin. “Ruth.”

Adeline felt something warm move through her, like dawn. She handed Ruth the charcoal.

“Then let’s begin,” she said.

Weeks passed. Then months. The lessons became routine, the way prayer used to be routine, except this prayer had teeth. Ruth learned quickly, hungry for every new piece of sense she could pull from the world. She wrote her name so many times her wrist cramped. She wrote it on scraps of paper, on the dirt, on the side of a crate with a piece of chalk stolen from a distant schoolhouse. Each time she wrote it, she looked up afterward as if daring someone to erase her.

Hart watched from the big house, resentment simmering, but he did not intervene. He made life hard in other ways: wages delayed, supplies rationed, rules tightened like a belt. Still the school held. It held because it was more than Adeline. It was a gathering of people who had learned, in small increments, that they could resist without swinging a fist, that they could survive without surrendering their minds.

One evening a storm rolled in off the river, sudden and violent. Rain hammered the roofs, wind snapped branches, and lightning turned the yard white for split seconds, exposing everything like a camera flash. Adeline stood in the cabin doorway, watching water run in sheets down the slope toward the quarters. She tasted fear, old and familiar, because storms had always meant danger here. Storms meant roofs collapsing and sickness spreading, meant people blamed for damage they could not prevent.

Behind her, Ruth sat at the table practicing letters by lanternlight. She looked up. “Miss Adeline?”

“Yes?”

Ruth held up her paper. In careful, uneven strokes, she had written two words.

BENJAMIN HALE.

Adeline’s breath caught. The name looked like a resurrection.

“How did you…” Adeline began.

Ruth’s mouth trembled with pride. “You told me letters are for remembering,” she said. “So I remembered him too.”

The storm raged outside. Inside the cabin, Adeline felt the world rearrange itself again, not in the dramatic way of war or law, but in the stubborn way of roots pushing through stone. Ben had taught Adeline to stay human. Adeline had taught Ruth to read. Ruth had written Ben’s name like a promise that the old erasures would not be allowed to win.

In the days after the storm, the big house roof leaked. One of the front columns cracked. Hart cursed and blamed the weather and the workers and God. But down at the cabin, people repaired what they could with their own hands, and Adeline moved through the quarters with herbs and boiled water and steady instructions, helping mothers keep their children from fever. Hart’s authority, once upheld by fear, now looked increasingly like a man shouting at rain.

That winter, a Bureau agent rode through again, his horse wet with sweat, his uniform dusty. He stopped at the cabin after hearing rumors of a school. He watched Ruth read from a tattered primer. He watched grown men struggle over words and refuse to laugh at themselves, because dignity was the point. When the agent looked at Adeline, his expression held surprise.

“You’re the planter’s daughter,” he said.

“I am,” Adeline replied.

“And you’re teaching freed people.”

“I am.”

He studied her, then nodded once. “Keep doing it,” he said. “They’ll fight you. But keep doing it.”

After he left, Hart sent word that Adeline was no longer welcome in the big house. The message came through Pruitt like poison delivered on a spoon. Adeline only nodded. She had already been exiled once. Being officially barred from a place that had never truly been hers felt like a strange kind of relief.

Years folded into each other. Ruth grew taller. Her reading became fluent, then confident, then powerful. She began helping Adeline teach the younger ones, her voice firm, her posture straight. When local white men muttered about “uppity” children and “dangerous schooling,” Ruth met their eyes and did not look away. Adeline watched her and felt the ache of a life she might have had if someone had taught her to stand sooner, and she also felt the quiet satisfaction of seeing the next generation stand anyway.

On a spring day when the cane shoots were bright and tender, Hart rode down to the quarters again. He was older now, his face drawn, his shoulders carrying the fatigue of a world shifting under him. He stopped by the cabin, not entering, but hovering near the doorway as if afraid the very threshold might accuse him.

Adeline stepped outside, wiping her hands on her apron. Ruth stood behind her, silent as a shadow but steady as stone.

Hart’s gaze flicked to Ruth, then back to Adeline. “They’re talking,” he said.

“Who is ‘they’ today?” Adeline asked.

Hart’s jaw tightened. “Neighbors. Planters. They say you’re poisoning people against their betters.”

Adeline’s eyes narrowed. “Are you their messenger now?”

Hart’s nostrils flared, but his anger didn’t fully ignite. Instead he looked tired, and that tiredness made him seem more human than Adeline had ever allowed herself to see.

“I can’t keep the place running like my father did,” he said, almost like an admission. “I don’t have his… appetite for it. And I don’t have the law behind me anymore.”

Adeline waited, sensing something important in the pause.

Hart swallowed. “If I sign leases,” he said slowly, “small plots. Let families farm for themselves and pay a portion back. If I… formalize wages. Keep records. Do it proper. Will your people stop leaving? Will they stop running off to Baton Rouge and New Orleans and wherever else they think the grass is greener?”

Adeline stared at him. In his voice she heard selfishness, yes, but also something else: fear of being left behind, fear of losing what little control he still had. She also heard the faint echo of Ben’s lesson. Sometimes freedom wasn’t about running. Sometimes it was about planting something where nothing good was supposed to grow.

“You want them to stay,” Adeline said.

“I want them to work,” Hart snapped, reflexive.

Ruth’s voice cut in, quiet but sharp. “We work already,” she said. “The question is whether we eat after.”

Hart’s eyes flashed toward her, offended, then hesitated. He looked at Adeline again, as if suddenly aware that the girl’s courage was not a fluke. It was a result.

Adeline spoke carefully. “If you want them to stay,” she said, “you treat them like people with futures. You give them a reason that isn’t fear.”

Hart’s jaw worked. “And if I do?”

Adeline’s gaze held steady. “Then the school stays,” she said. “And maybe, just maybe, this land stops being only a graveyard of other people’s lives.”

Hart stood still for a long moment. Then, almost grudgingly, he nodded.

“Fine,” he muttered. “We’ll try it.”

After he left, Ruth looked at Adeline, eyes wide. “Did we just…” she began.

“Win?” Adeline finished, her mouth curving. “No. Not like a storybook. But we moved the line.”

That summer, paper agreements were drawn up. Not perfect. Not generous. But real enough to hold Hart accountable if he tried to cheat too blatantly. Families planted gardens that belonged to them in a way nothing ever had before. Children came to the cabin with full bellies more often than not. Ruth wrote names into a ledger. She wrote births. She wrote marriages. She wrote deaths too, because history didn’t stop being cruel just because people were allowed to spell it.

One evening, Ruth found Adeline sitting alone by the doorframe, fingers resting on the carved names. The air was warm, filled with cricket song and the distant hush of cane leaves rubbing together.

“You’re getting tired,” Ruth said softly.

Adeline smiled without looking up. “I’ve been tired since I was a girl,” she replied. “I just didn’t always know it.”

Ruth sat beside her, close enough that their shoulders almost touched. “I’m going to keep teaching,” Ruth said, not as a promise to Adeline, but as a vow to the world. “Even if you… even if you’re not here.”

Adeline turned her head then, studying Ruth’s face. The girl was no longer a girl. She was a young woman with steady eyes and a spine that did not bend easily. In her, Adeline saw the continuation of Ben’s stubborn dignity, traveling forward like a torch passed hand to hand.

“You will,” Adeline said. “Because you know the secret now.”

Ruth’s brow furrowed. “What secret?”

Adeline tapped the wood lightly, the names making their quiet claim. “That they can take land,” she said, “and they can take years, and they can take your body if they can trap it. But they can’t take the part of you that refuses to be a thing. Not unless you hand it over.”

Ruth swallowed hard. “And you didn’t.”

Adeline’s eyes softened. “Not after Ben,” she said. “Not after I learned how to say no.”

When Adeline died, it was in early autumn, when the air first began to cool and the cane fields rustled like restless skirts. She passed in the cabin, the same place she had once been delivered as a punishment and had turned, slowly, into a sanctuary. Ruth held her hand, the way Adeline had held Ben’s, and whispered words Adeline had taught her long ago, letters assembled into prayer.

Outside, children waited, quiet and solemn, their faces lit by lantern glow. Some of them could not remember a time when the cabin had not been a school. To them, Adeline was not the planter’s hidden daughter. She was simply Miss Adeline, the woman who made their names feel permanent.

Afterward, Ruth took a knife and carefully refreshed the carved letters on the doorframe, deepening them so time would have to work harder to erase them. Then she added one more mark beneath, smaller than the others, a line of words she wrote with her own hand on a thin strip of wood and nailed in place.

WE WERE HERE. WE WERE HUMAN.

Years later, people would argue about what freedom had meant in Louisiana, about whether anything truly changed or if it only changed clothes. They would point to sharecropping and debt and violence and say, Look. The chains are still there, just quieter. And they would not be wrong.

But in a weathered cabin beyond the hill’s shadow, children learned to read anyway. Names were spoken out loud. Stories were written down. And on days when the world tried to shrink them, they stood in the doorway, touched the carved letters, and remembered that someone before them had looked power in the face and refused to crumble.

Sometimes freedom didn’t arrive like a trumpet.

Sometimes it arrived like a woman tracing an A in the dirt, and a man learning to write his name, and a girl named Ruth holding a piece of charcoal like it was a key.

And sometimes, that was enough to change everything that mattered.

THE END

News

OUTTAKES FROM A WINTER RING

(An extra story that explains the hidden twist behind Tomas Crowe, the “seven cents,” and why Evelyn Harrow watched Benita…

FARMER WHO BOUGHT A GIANT SLAVE FOR SEVEN CENTS… AND TRAINED HER IN SECRET

They laughed before the auctioneer even finished clearing his throat. The February air in Natchez, Mississippi, sat heavy on the…

SHE TRADED ONE NIGHT FOR A LIFE… AND HER CEO’S GUILT OPENED A WAR

Sienna Alvarez had learned that hospitals don’t really sleep. They dim their lights and lower their voices, but the place…

THE PLANTATION OWNER GAVE HIS SILENT, HEAVYSET DAUGHTER TO THE STRONGEST ENSLAVED MAN… AND NO ONE IMAGINED WHAT HE WAS REALLY HOLDING

The heat in the Lowcountry didn’t simply sit on the land, it pressed down like a judgment. On the veranda…

The mistress had three twins and ordered the slave to k!ll the one with the most different skin color – but fate had other plans.

The night Magnolia Ridge Plantation learned it was being tested, March rain fell like a stern sermon over the Mississippi…

THE BANQUET OF ELEVEN PLANTERS: THE MYSTERIOUS NIGHT AT OAK HOLLOW, LOUISIANA

No one who crossed the threshold of Oak Hollow on the night of December 14, 1873, believed they were walking…

End of content

No more pages to load