The men at the courthouse steps called him Hank the Ox the way boys call a storm “nothing” to convince themselves it can’t hurt them.

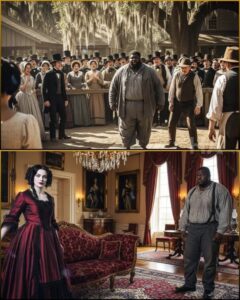

He stood in the August heat like a fallen column somebody had forgotten to haul away, thick-shouldered and wide through the middle, his shirt strained tight over a belly that rose and fell like a slow bellows. One eye wandered a little, giving his face a permanent question-mark look. His front teeth were uneven, one chipped so badly it seemed sharpened on purpose. When he breathed through his mouth, a thin shine gathered at the corner of his lip, and the crowd used that small humiliation like proof that God had stamped him with worthlessness.

“Hank can’t count past his own fingers,” a man in a straw hat said loudly, as if Hank were a fence post. “That’s why he’s still alive.”

The auctioneer, Tobias Rusk, wiped sweat from his neck and tried to sound businesslike. “Forty-two years old. Field hand. Strong as a mule when he’s pushed. Eats like two. Talks slow. You won’t get poetry out of him, but he’ll move your stones.”

Silence answered. The Morrison estate had been bled dry by debt, and now its human inventory stood lined on a platform, each person reduced to a list of useful features. Strong backs were already taken. The ones with pretty faces had buyers. The ones whose eyes held too much fire, too much refusal, had been inspected and passed over by men who didn’t want trouble with their morning coffee.

Hank was trouble of a different kind. Trouble to look at. Trouble to imagine in a fine house. Trouble to explain to your wife.

That’s when the woman arrived.

She came late on purpose, not hurrying, not apologizing, letting her carriage wheels speak for her before her voice ever did. In coastal Georgia society, a late entrance wasn’t a mistake. It was a reminder. People turned like sunflowers toward her, squinting against her brightness.

Her name was Lydia Wainwright, and even those who hated her said it like it tasted expensive.

At twenty-five, she wore widowhood the way other women wore pearls: as proof she had been chosen, and as warning she no longer needed anyone’s permission. The pale dress clung neatly at her waist, clean as a sheet in a room where no one else could afford soap. Dark hair, pinned back. Gloves. A parasol with lace so delicate it looked like it would wilt if anyone breathed too hard.

Rumors came attached to Lydia like burrs. Her husband, an old planter with sugar on his tongue and cruelty in his hands, had died “peacefully” in his sleep. Some said he had simply been ready. Others said a woman as lovely as Lydia didn’t become a widow that conveniently unless she knew how to open and close doors the right way, including the final door.

She stepped from her carriage and walked toward the platform. The men made room, automatically. Women’s eyes followed her, measuring, comparing, tightening.

Lydia looked up at the line of enslaved people like she was choosing a ribbon. Her gaze skated past the young and strong. She didn’t pause for the proud. She didn’t even notice the pretty.

She stopped at Hank.

The crowd leaned in, hungry for a story. Lydia’s mouth lifted, not a smile exactly, but the beginning of one. The kind that promised entertainment at someone else’s expense.

“That one,” she said, pointing with the tip of her parasol as if she might get dirt on herself by using a finger. “The grotesque one.”

A ripple of laughter rolled through the men. Even Tobias Rusk blinked, confused, then grateful. A bid was a bid.

“Ma’am,” he said, “are you certain? I have house servants. Educated ones.”

Lydia’s eyes went cold enough to crack glass. “Did I stutter?”

“No, ma’am,” he rushed. “Starting bid, twenty dollars.”

No one answered. No one wanted him. No one wanted to pay to be reminded that bodies could be ridiculous, that the world could produce a man like Hank and simply keep going.

Lydia lifted her chin. “Thirty-five.”

Tobias slapped his gavel down like it was a joke landing clean. “Sold, to Mrs. Lydia Wainwright, for thirty-five dollars.”

More laughter, brighter now, because the punchline had become real.

One of Lydia’s friends, a tall woman with a tight mouth, leaned close to her. “Lydia, darling,” she whispered, “what on earth do you want with that… thing?”

Lydia’s eyes glittered, enjoying the word. “Pretty toys break too easily,” she murmured. “And people expect you to treat them gently. But something ugly, something nobody will miss… I can do whatever I please. And no one will care.”

Hank stood with his head bowed, swaying as if standing were a new skill he hadn’t mastered. He didn’t look up. He didn’t flinch. He merely breathed.

If anyone had been close enough to watch his hands, they might have noticed his fingers twitching once, twice, as though tapping on an invisible tabletop.

Counting.

Not to five.

To something far more dangerous.

The plantation was called Marrowfield, a name that sounded elegant until you understood what it meant. It sat miles from town, draped in live oaks that held Spanish moss like funeral lace. The big house rose at the end of a long drive, white columns shining like bone. In the distance, fields stretched flat and wide, stitched with rows where human backs bent toward the dirt.

Lydia waited on the steps when the wagon arrived, as if she couldn’t bear to be indoors while her new purchase came onto her property. The overseer beside her stood stiff, hat in hand, pretending not to exist unless she spoke to him.

They led Hank down from the wagon. He moved slowly, heavy feet dragging in the dust, shoulders hunched like he expected the sky itself to strike him.

“Bring him inside,” Lydia said.

The man holding Hank’s chain hesitated. “Ma’am, he’ll dirty the—”

“Inside,” she repeated, and the word made the air snap.

They brought Hank into the parlor.

The room smelled of polished wood and old perfume. Velvet chairs sat like bored royalty. A piano gleamed in the corner. Oil portraits stared down with painted dignity, faces that had never been told no.

Hank stood near the doorway, too large for the delicate space, breathing with his mouth open like a tired animal. Lydia moved toward him with slow, deliberate steps, circling as if he were a new breed of dog.

“Hank,” she said, drawing the name out, softening it like she was speaking to a child. “Do you understand me?”

He nodded too eagerly. His chin bobbed. Drool glimmered, just a little.

Lydia’s smile sharpened. “Here are the rules. You belong to me now. You will live in the small room off the kitchen. You will do what I tell you when I tell you. If you amuse me, you’ll be fed. If you disappoint me… you’ll learn what disappointment feels like.”

Hank’s eyes stayed unfocused, as if her words floated past him like dust motes in sunlight.

“Do you understand?” she asked again.

He nodded again, exaggerated, obedient.

“Good,” Lydia said. “Tomorrow we begin.”

She turned to the older enslaved woman standing quietly by the doorway, her posture straight with the practiced invisibility of someone who had survived too long to waste energy on hope. Her name was Ruth, and her eyes held the kind of attention that didn’t look like staring but missed nothing.

“Ruth,” Lydia said, “see to him. Wash him. If you can call it that. And if he soils my rugs, I’ll take it out of you.”

Ruth lowered her gaze. “Yes, ma’am.”

Hank shuffled after Ruth, leaving the parlor like a stain Lydia had chosen to place on her own furniture.

Upstairs, alone in her bedroom later, Lydia stood before a mirror and loosened her gloves with careful fingers. She watched her own face as if checking it for cracks.

“Ugly things are honest,” she told her reflection softly. “Pretty things lie.”

She did not notice the servant boy in the hallway pausing, listening, then hurrying away with his head down as if words could bruise him.

And she did not notice that the new “toy” she’d bought for laughs was, in fact, a man who had spent the last two years building a mask so convincing that even cruelty would never think to question it.

His true name was Dr. Nathaniel Hart.

He had been born free in New York, raised by parents who had run north long before their bodies could be tagged and sold. His mother taught him letters the way people teach prayers, believing knowledge was the only roof no one could burn down. His father worked docks and saved pennies like they were seeds.

Nathaniel’s mind had arrived hungry.

By fifteen, he solved proofs that left grown men blinking at paper. By twenty-five, he taught mathematics in Philadelphia at a small school for free Black students, his chalk moving across the board like a violin bow. He spoke about numbers the way some people speak about God, not as a weapon but as a language that revealed truth whether the powerful liked it or not.

And truth, in America, was never safe.

A slave catcher named Silas Drummond found a thread to pull. Nathaniel’s parents, he claimed, had belonged to a Georgia plantation decades earlier. Drummond forged papers. He found a judge who valued whiteness more than evidence. Under the new Fugitive Slave Act, a free man could be swallowed by ink.

Nathaniel ran.

But running wasn’t enough. Drummond had money in his eyes and law behind his grin. Nathaniel needed more than distance. He needed invisibility.

So he built Hank the Ox.

He gained weight deliberately, turning his body into a disguise nobody would admire. He studied the dismissed: men with stutters, men with vacant stares, men whose clumsy movements made others look away. He practiced slack-jawed silence. He learned to drool on command. He broke one tooth himself, a sharp moment of pain traded for a lifetime of being underestimated. He trained one eye to drift, not enough to be dramatic, just enough to make people assume his mind drifted too.

Then he walked into Georgia like a man wandering into his own grave.

He let himself be caught. Let himself be beaten. Let himself be bought cheap and laughed at, because laughter was a veil. Men did not look closely at what disgusted them. They did not imagine strategy in something they had already labeled worthless.

All the while, Nathaniel listened.

Because he had a different kind of mathematics to solve. Not equations on a chalkboard, but the arithmetic of slavery’s money: who financed it, who insured it, who pretended to be righteous while quietly counting profit.

And Lydia Wainwright’s late husband had been more than a planter. He had been a node in a network that reached north, into banks and shipping companies and polite drawing rooms where people said “civilization” while sipping tea sweetened by blood.

When the old man died, Lydia inherited not just Marrowfield, but his ledgers, his letters, his hidden partnerships.

To expose the system, Nathaniel needed access to the heart.

As a field hand, he would never enter the house except to be punished. As Lydia’s “toy,” he would be dragged into the parlor, placed in corners, made to serve as furniture for her cruelty.

It was a vile opportunity.

It was still an opportunity.

Lydia’s “training” began with humiliation dressed up as entertainment.

She made Hank crawl across polished floors while her friends laughed over lemonade. She balanced trays on his head and slapped his hands if they trembled. She ordered him to eat scraps from a dog bowl “because it suits him,” and when he hesitated for half a breath, she snapped, “Don’t make me regret buying you.”

He obeyed.

He performed stupidity like a hymn. He sang children’s songs in a thick, slurred voice when commanded. He danced clumsily, letting his big body shake, letting the ladies shriek with delight at his ugliness.

But while Lydia thought she was breaking him, he was collecting facts the way his mind had always collected patterns.

He learned the house’s rhythms. He learned which steps creaked near the east hallway. He learned Ruth’s schedule, the cook’s schedule, the times Lydia drank too much wine and grew careless with her tongue.

Most of all, he learned Lydia’s favorite mistake: talking as if enslaved people were air.

Her attorney visited. Business partners came, men with rings that flashed like knives. They spoke of shipments and “stock,” of bribes and customs papers, of northern loans laundered through respectable institutions. Lydia listened like a queen, bored but pleased, and Hank stood in the corner with his mouth slightly open, eyes unfocused, drooling faintly, a human decoration with no supposed capacity to understand numbers.

Nathaniel understood every number.

He built a mental map: names, dates, amounts. Routes from Savannah to smaller coastal landings. Codes in letters. Accounts hidden behind other accounts. The quiet hypocrisy of men in Boston who donated to churches while investing in chains.

And then he learned where Lydia kept the proof.

It came by accident, the way secrets often do.

One evening, Lydia sat in her bedroom with a glass of sherry while her maid helped her unpin her hair. Lydia complained about her late husband, the way widows sometimes do when they believe death has absolved them of politeness.

“He even locked his blasted records behind a painting,” Lydia muttered, rubbing her temples. “As if his own wife couldn’t be trusted.”

“What painting, ma’am?” the maid asked softly.

“The wedding portrait,” Lydia said. “And the code is the date, because he was sentimental in his rottenness.”

Nathaniel stood nearby holding a laundry basket, swaying, eyes dull.

But inside his skull, the information clicked into place like a key turning.

The first time he dropped the mask was not dramatic.

It was practical.

Rain fell hard one October night, drumming the roof like impatient fingers. Lydia hosted a small dinner, showed off “the Ox,” and made him kneel while guests tossed crumbs at him as if feeding a pig. They laughed until their cheeks shone with it. Afterward, drunk on cruelty and wine, they left.

The house quieted. Lamps dimmed. Doors shut.

Nathaniel cleaned slowly, deliberately, giving the household time to sink into deep sleep. Then, when the clock in the hallway sighed past two, he stood in the kitchen’s shadow and let Hank the Ox slide off him like a heavy coat.

His posture straightened. His eyes focused. His breathing steadied.

Ruth, coming down for water, froze when she saw him.

For a heartbeat, they stared at each other in the dark, two people meeting without permission.

Nathaniel lifted a finger to his lips. Not because he feared Ruth, but because sound could be fatal.

Ruth’s gaze sharpened, and something like understanding moved across her face. She didn’t speak. She simply stepped back into the shadows and let him pass, her silence a door opened.

Upstairs, Nathaniel approached Lydia’s balcony window. He had noticed the latch weeks ago, loose from years of neglect. He worked it carefully, hands steady. The window eased open.

Lydia slept, sprawled in white sheets, her face relaxed into softness that almost looked innocent if you didn’t know what she did with her waking hours.

Nathaniel ignored her and went straight to the portrait. Lydia and her old husband stared down in painted bliss, frozen in a lie.

Behind the frame, the safe waited.

He dialed the code: the wedding date, as Lydia had complained.

The lock clicked.

Inside, ledgers lay stacked like the spine of a beast. Letters. Contracts. Bank documents. Lists of names that had never been intended for daylight.

Nathaniel did not take them. Taking them would be noticed.

Instead, he read.

His mind became a camera, a vault. He swallowed pages. He memorized columns. He turned the pages with fingers that did not tremble, and every number he stored was a nail in Lydia’s future coffin.

Then Lydia shifted in bed.

Nathaniel froze, heart thundering against his ribs. For a sharp moment, he imagined her eyes snapping open and seeing him, not Hank, not the drooling fool, but a man with intelligence in his face.

Lydia mumbled something, rolled over, and fell back into heavy sleep.

Nathaniel waited until his pulse stopped shouting. He closed the safe, reset the portrait, slipped back through the window, and returned to the small room off the kitchen.

By sunrise, Hank the Ox was back: hunched, slow, vacant.

But now the evidence lived behind his eyes.

Now he had what he’d come for.

The problem was escape.

If he ran, Lydia would punish the innocent. She had already proven she enjoyed hurting people who hadn’t even disappointed her, simply because she could.

Nathaniel needed a path that didn’t leave a trail of bodies behind him.

So he devised a quieter kind of trick.

He began to “forget” food.

Not in a way that looked like rebellion. In a way that looked like stupidity.

When given cornbread, he stared at it as if unsure what it was. He took a bite, chewed slowly, then wandered away distracted. Over days, his cheeks hollowed a little. His shoulders slumped more. He moved as if his body were turning to mud.

Lydia noticed, not with concern, but with annoyance.

“My toy is breaking,” she snapped one afternoon. “Ruth, do something. I paid for him.”

Ruth kept her face smooth. “He need medicine, ma’am. From town.”

“I’m not paying a doctor for that thing.”

“There’s a healer in Savannah,” Ruth said carefully. “The church on West Broad. They tend to the sick, no charge. If you send him for a few days, maybe he’ll come back fit enough to amuse you again.”

Lydia considered, tapping her finger against her teacup. She did not want to lose her entertainment. She did not want to waste money. She did want to feel merciful without spending a dime.

“Fine,” she said. “One week. And if he doesn’t return, I’ll whip every back on this property until someone tells me who helped him.”

Ruth’s breath caught, but she lowered her head. “Yes, ma’am.”

Nathaniel kept his eyes unfocused. But inside, hope flared like a match.

Savannah meant crowds. It meant a free Black community. It meant whispers of the Underground Railroad moving like water through cracks.

It meant possibility.

The next morning, Ruth drove the wagon herself.

They rode past fields and trees and the slow curve of the road toward the city. For miles, Ruth said nothing. Nathaniel kept his posture slumped, his mouth open, his eyes dull.

Only when Marrowfield had shrunk into distance did Ruth speak, her voice low.

“I don’t know who you are,” she said. “But I know you ain’t what you pretend.”

Nathaniel’s heart tightened. There were traps in the world that sounded like kindness.

Ruth glanced at him, her eyes steady. “I seen you watch. I seen you listen. And I seen you move one night like a man who knew where he was going.”

Nathaniel held the mask a moment longer, weighing risk like a mathematician weighing variables.

Then he let Hank fall away.

He straightened. He met her gaze with his real eyes. When he spoke, his voice was educated, clear, a sound that did not belong to a drooling fool.

“My name is Dr. Nathaniel Hart,” he said softly. “I teach mathematics. Or I did. I’m being hunted. And I’ve been gathering evidence against Lydia Wainwright and her partners.”

Ruth’s hands tightened on the reins. “Lord have mercy.”

“I need to get this information north,” Nathaniel said. “But I can’t run without her punishing everyone on that plantation. I won’t trade your lives for mine.”

Ruth was quiet long enough that the wagon wheels filled the silence with their steady thump.

Then she nodded once. “Reverend Daniels,” she said. “African church. He been helping folks disappear since before I was born.”

Nathaniel’s throat tightened with something dangerously close to gratitude.

Savannah rose ahead, humid and busy, streets loud with carts and voices. Ruth drove toward a modest church, its paint worn but its doors open.

Inside, Reverend Moses Daniels greeted them with the calm of a man who had held fear in his hands so often it no longer surprised him.

In a back room that smelled of herbs and old wood, Nathaniel spoke for hours.

He recited names and numbers. He listed shipping routes. He described accounts. He repeated exact language from letters, the way a man recites scripture. Two visitors from the American Anti-Slavery Society, in town by chance and by providence, wrote until their hands cramped.

One of them, a Quaker named Thomas Garrett, stared at Nathaniel like he’d been handed lightning in a jar. “You’re telling me you memorized it,” he whispered.

Nathaniel nodded. “I couldn’t take it. So I became it.”

Garrett’s mouth opened, closed. “This could ruin them,” he said finally. “North and South. Banks. Politicians. Insurance men. It could show the whole country what it’s made of.”

“It must,” Nathaniel said.

“And you want to go back?” Garrett asked, horrified. “That woman will kill you.”

“She won’t,” Nathaniel said, and his voice held a cold certainty that didn’t come from bravery but from understanding Lydia’s greatest weakness. “She can’t imagine intelligence inside a body she despises. Her prejudice is my armor.”

Reverend Daniels leaned forward. “If you go back, you must go back with a promise,” he said. “A promise that when the time comes, you won’t hesitate.”

Nathaniel met the Reverend’s eyes. “When the time comes,” he said, “I’ll step into the light and let her see exactly what she bought for laughs.”

He paused, then added softly, “But no one at Marrowfield will pay for my escape.”

Ruth’s jaw tightened. “We already paying,” she muttered. “Every day.”

Nathaniel swallowed, feeling the weight of the truth in her words.

He returned a week later as promised.

He climbed back onto Lydia’s property in his mask of ugliness and emptiness, and Lydia clapped her hands like a child receiving a toy back from repair.

“There you are,” she said. “Did the church fix you?”

Hank nodded too eagerly, drooling faintly.

“Good,” Lydia said. “I was bored.”

Seven weeks passed, each day a tightening string.

Nathaniel continued to endure. Lydia continued to invent ways to humiliate him, and he continued to survive them, because he had learned something essential: cruelty wanted reaction. Deny it reaction, and it grew sloppy. It grew careless. It began to believe its own power was absolute.

And then, on a cold morning in December, the world arrived at Marrowfield with boots and paper.

Federal marshals rode up the drive. Behind them came men from northern banks with sharp faces and sharper intentions. And behind them, like flies that smelled a feast, came journalists with notebooks and eager eyes.

Lydia was in the parlor, sipping tea, Hank standing in the corner balancing a tray on his head because she’d decided the sight pleased her.

The lead marshal stepped inside without waiting to be announced. He unfolded a warrant.

“Mrs. Lydia Wainwright,” he said, voice carrying. “You are under arrest for illegal trafficking, fraud, and conspiracy.”

For a moment, Lydia simply stared as if the words were a language she didn’t recognize.

Then her face flushed red with rage. “This is absurd. Do you know who I am?”

“We do,” the marshal said. “And we know what your late husband was. We have records. Names. Accounts. Letters.”

“That’s impossible,” Lydia hissed. “Those records are locked—”

“Behind your wedding portrait,” a voice finished from the doorway.

Everyone turned.

Hank the Ox stepped forward, and in that single movement, the room changed.

His shoulders rolled back. His gaze sharpened. His mouth closed. The droop vanished, not like an act ending, but like truth rising.

He looked thinner, suddenly, though his body hadn’t changed. It was the posture that transformed him, the dignity that made his bulk irrelevant.

He spoke again, and the educated cadence sliced through the parlor like a clean blade.

“My name is Dr. Nathaniel Hart,” he said. “And Hank the Ox never existed.”

Lydia’s teacup slipped from her fingers and shattered on the floor.

Her eyes widened as recognition collided with disbelief. “You,” she whispered. “You can’t be…”

“I was in your house,” Nathaniel said calmly. “In your meetings. In your bedroom. In your secrets. You spoke in front of me because you believed I was furniture.”

Lydia’s lips trembled, rage and humiliation warring. “You’re property,” she spat, reaching for the old weapon. “Your word means nothing.”

“I was born free,” Nathaniel said. “And your paperwork cannot change that. But even if I had been enslaved, your crimes would still be crimes.”

The marshal nodded to his men. “Search the house.”

They moved upstairs. Lydia lunged forward, wild. “Stop them! Stop them!” she screamed, but the room had shifted. The power she’d worn like perfume was suddenly thin.

Two minutes later, a marshal returned carrying ledgers bound in leather.

Lydia’s face went paper-white.

Nathaniel watched her, not with triumph, not even with hatred, but with the steady gaze of a man who had survived by seeing reality clearly.

“I endured you,” he said softly. “Not because I was weak. Because I was patient. Because I wanted the whole country to see what hides behind beautiful curtains.”

Lydia’s voice cracked. “I can pay you,” she whispered, desperation scraping away her polish. “Whatever you want.”

Nathaniel leaned closer, his voice low enough that only she could hear. “For months you made me eat like an animal,” he said. “You built joy from suffering. And you never once wondered if the ‘ugly’ thing you bought had a mind. That blindness… was your biggest mistake.”

He straightened. “You lose.”

The marshals placed shackles on Lydia’s wrists. The metal looked obscene against her pale gloves. She tried to stand tall, but her knees trembled.

As they led her out, she turned once, eyes burning. “You’ll regret this,” she hissed.

Nathaniel’s expression did not change. “No,” he said. “I’ll remember it.”

The story traveled faster than winter wind.

Newspapers printed sketches of Hank the Ox beside Dr. Nathaniel Hart, the contrast so dramatic people swore it couldn’t be real. Editors who had never cared about enslaved people cared about scandal, and scandal made the truth slip into rooms it had never been allowed to enter.

Northern banks were named. Southern partners were exposed. Men who had preached morality were revealed counting profit. Licenses were revoked. Politicians resigned. The network Lydia’s husband had helped maintain cracked under daylight.

Lydia was sentenced to prison. Her plantation was seized. The people she had owned were freed, not as a gift but as a correction too late for the years stolen from them.

Ruth stood at the edge of Marrowfield one morning as wagons carried families north, and she watched the big house shrink behind them like a bad dream losing shape.

Nathaniel found her before he left.

“You saved lives,” he told her.

Ruth looked at him with tired eyes. “Don’t make me a saint,” she said. “I did what I could.”

Nathaniel nodded, accepting the truth in that. “Then let me do what I can,” he said. He placed a folded letter in her hand. “If you ever need help in Philadelphia… take this to Reverend Brown on Lombard Street. He’ll know what to do.”

Ruth stared at the letter as if it might bite. “You going back to teaching?” she asked.

Nathaniel looked toward the road, where the future waited uncertain and hard. “Yes,” he said. “Because numbers are honest. And this country has lied to itself too long.”

Ruth’s mouth tightened, fighting emotion. “They laughed at you,” she said. “All them folks.”

Nathaniel’s gaze softened. “Let them laugh,” he said. “It kept me alive.”

Years later, in a classroom in Philadelphia, Nathaniel stood before a chalkboard and told his students about underestimation, about how cruelty blinded itself by believing appearances were destiny.

“They called me worthless,” he said, chalk tapping once against the wood. “And that word became my hiding place. Not because I agreed with it. Because my enemy did.”

A student asked, quiet, “Do you regret what you endured?”

Nathaniel paused, the room holding its breath.

“I regret the world that made it possible,” he said finally. “But I don’t regret the outcome. Because every humiliation proved something important: dignity doesn’t live in a body’s shape or a face’s symmetry. It lives in the will that refuses to be defined by someone else’s cruelty.”

Outside, the city moved on, busy, imperfect, alive. Inside, the lesson took root.

A woman once bought “the Ox” for laughs, believing ugliness meant emptiness and weight meant weakness.

Instead, she bought her own ruin.

And she never saw it coming.

THE END

News

Because she needed heirs, the widow chose a slave to “EXECUTE AN UNEXPECTED PLAN” for her three daughters. And in doing so, the widow herself created a shocking secret…

Winter didn’t arrive in central Virginia with trumpets. It slipped in like a quiet creditor, collecting warmth from the fields…

The Farmer Who Bought the Most Beautiful Slave, But Regretted It the Next Day

the air over Ashlawn Farm tasted like wet earth and old smoke, the kind that clung to a man’s throat…

HE MARRIED HIS OWN ENSLAVED COOK AS A BET… AND THE BAYOU KEPT THE RECEIPTS

The marriage certificate still exists in Baton Rouge, in a quiet room where history is kept like old bone. Paper…

THE PLANTATION LORD HANDED HIS “MUTE” DAUGHTER TO THE STRONGEST ENSLAVED MAN… AND NO ONE GUESSED WHAT HE WAS REALLY CARRYING

The Georgia sun didn’t shine so much as it ruled. It pressed down on Whitaker Plantation with the confidence of…

No Mail-Order Bride Lasted One Week with the Mountain Man… Until the Obese One Refused to Leave

They always told the tale the same way, like it belonged to the fire more than it belonged to any…

He Dumped Her For Being Too Fat… Then She Came Back Looking Like THIS

In Mushin, Lagos, there are two kinds of mornings. There’s the kind that smells like hot akara and bus exhaust,…

End of content

No more pages to load