The first thing the maids noticed was the quiet.

At Magnolia Reach, quiet was never innocent. Quiet meant a storm had changed its mind and decided to sneak in through a crack in the sky. Quiet meant a horse had gotten loose in the lower pasture. Quiet meant someone important had slammed a door so hard the house held its breath afterward.

This quiet, on that suffocating August morning of 1858, was the kind that sat on your tongue like metal.

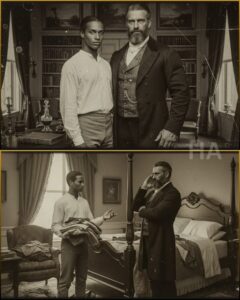

Addie Lou, who had cleaned the upstairs rooms since she was twelve, pushed open the master bedroom door with her elbow, a linen basket balanced on her hip. Behind her, two other women hovered in the hallway, hands damp, eyes fixed on the floorboards as if looking up might become an accusation.

The curtains were half drawn, turning the sun into a pale smear. In that dimness, Colonel Silas Wainwright lay sprawled in his silk sheets, the covers twisted as though he’d wrestled them in his sleep. His face had stopped being a face. It was an expression, carved sharp by whatever last feeling had seized him: pain so fierce it should’ve been a scream, and something else threaded through it like a cruel joke. Rapture. Relief. A terrible, private peace.

But what froze Addie Lou wasn’t the dead white man.

It was the person curled against his chest, breathing softly, one hand splayed across the colonel’s sternum as if keeping time with a heartbeat that had already left.

A slave.

Young, maybe twenty-three. Skin the color of polished pecan. Hair pulled back, neat. Bare feet on Egyptian cotton. And a calmness so complete it looked like defiance.

Addie Lou’s basket slid from her arm and hit the rug with a muffled thump.

The sleeper’s eyes opened.

Not startled. Not guilty. Just awake, like a cat that knows exactly where it belongs even in the wrong room.

“Morning,” the slave said quietly, voice rough with sleep.

The hallway maids made a sound that was half prayer, half choke.

Addie Lou backed out as if the air in the room had turned to boiling water. She didn’t run. Running brought questions. She walked fast, because fast could still be called work.

Downstairs, the house filled with whispers like smoke.

By breakfast, the overseer had already sent a rider into Natchez for the doctor.

By noon, Magnolia Reach had become a rumor with a roof.

And by the next day, the entire county was repeating the same sentence with different flavors of disgust:

They found the colonel dead… and that thing in his arms.

No one said the slave’s name out loud at first, as if naming might summon the truth into their own parlor. But names are stubborn. They float. They stick to people’s lips. They hatch in the heat.

Rowan.

Rowan Wainwright’s “special attendant,” though the law did not recognize specialness in property.

Rowan, whose body defied the tidy compartments white society used to keep its world from spilling.

Rowan, who had lived inside the mansion for eight years like a secret stitched into the lining.

Rowan, who—when the doctor examined them and went pale as milk—was revealed to have anatomy the physicians of Mississippi could not explain in anything but frightened Latin.

Rowan, who, by the time the coroner stopped shaking, was said to be carrying a child that should not have been possible at all.

And then, like a match tossed into dry straw, the question caught fire:

What in God’s name had Silas Wainwright been doing behind those closed doors?

Eight years earlier, Rowan’s story began the way so many stories began in that part of America: with a gavel, a ledger, and the sound of a human being priced like a mule.

New Orleans, September of 1850, was all wet heat and sweet rot. The slave market on Chartres Street worked with the efficiency of any other exchange, except the merchandise breathed and prayed.

Silas Wainwright stood near the back, hat in hand, trying to ignore the sweat that made his collar feel like a rope. He was forty-two then, built like the kind of man who had never needed to ask twice. His plantation outside Natchez spread across three thousand acres, the cotton fields laid out like white scars. He’d inherited land, then doubled it. Married into money, then multiplied it. His name sat cleanly in church records and business contracts, polished by reputation.

His wife, Eleanor Whitcombe Wainwright, was Virginia blood, raised on rules and linen and the quiet cruelty of “proper.” Their marriage had been arranged when she was seventeen. They had two daughters, both pretty, both practiced, both already learning how to smile without showing their teeth.

Silas came to New Orleans for field hands. He had sold a few men the year before to pay a gambling debt he pretended didn’t exist, and the fields did not forgive shortages.

He had no intention of purchasing anything “unusual.”

Then Lot Forty-Seven stepped onto the block.

The auctioneer’s voice sharpened. “Lot Forty-Seven. Called Rowan. Approximately fifteen. Origin Louisiana. Unique physical characteristics noted. Full disclosure documentation available to serious buyers.”

The crowd shifted the way a flock of birds shifts, all instinct and unease. Several men who had been leaning forward moments before suddenly leaned away, as if the air around the lot carried illness.

Silas noticed.

Curiosity is a dangerous hunger in a man who’s never been told no.

“What’s the starting bid?” someone asked, sounding like they already regretted speaking.

“Two hundred dollars,” the auctioneer said too quickly. “Buyer assumes all associated complications.”

Silas lifted his hand. “Two hundred.”

The room went oddly silent. No one countered. The auctioneer slammed the gavel down like he was eager to get rid of a cursed object.

“Sold. Colonel Wainwright of Mississippi.”

In the office, the clerk handed Silas the bill of sale and a sealed envelope. His eyes flicked away as if the paper could burn.

“You’ll want to read that, Colonel. Company policy.”

Silas broke the seal. The words were clinical, careful, pretending the page itself could be neutral.

Rowan possessed sex characteristics of both male and female development, described as formed and, according to the examining physician, “apparently functional.”

Silas read it twice. His hands trembled, and he did not know if it was shock or recognition or something uglier wearing one of those masks.

He glanced through the office window.

Rowan stood in the holding area, eyes down, posture trained into submission. But there was something in the stillness of their shoulders that wasn’t meekness. It was endurance. The kind that learns to be quiet so the world doesn’t hear you bleeding.

Silas signed the papers anyway.

And as he did, a woman in the corner of the market watched him the way a hawk watches a rabbit.

Her name was Mei-Lin Carter.

She belonged, on paper, to a Charleston dealer who specialized in “exotics,” half spectacle, half servant. Her mother had been Chinese; her father, Black. Mei-Lin’s value in white eyes was her rarity. Her true value was her mind.

She watched Silas Wainwright read the disclosure.

She watched his face change.

And she knew, the way some people know rain before the sky admits it, that this sale would not end with cotton.

The journey to Natchez took three days by carriage and riverboat. Silas insisted Rowan ride inside with him “to prevent escape,” but the truth sat sharper: he could not stop looking at them without feeling the floor under his life tilt.

On the second evening, with swamp dusk turning the world into a bruise, Silas asked the question he’d been chewing until his teeth hurt.

“How do you think of yourself?” he said. “As male or female.”

Rowan looked up. Met his gaze.

A slave meeting a white man’s eyes was a spark near gunpowder. Silas should have slapped them for it, if he wanted to keep the laws of his world intact.

Instead, he found himself holding the gaze like he was thirsty.

“I think of myself as Rowan, sir,” they said softly. “The world demands I be one or the other. But God made me… more complicated.”

Silas’s breath caught.

Rowan continued, voice steady. “People get angry when they can’t sort something. It makes them feel… powerless.”

Silas stared, stunned by the precision. He’d expected fear. He’d expected pleading. He hadn’t expected insight.

“Can you read?” he asked abruptly.

“Yes, sir,” Rowan said. “My first owner’s wife taught me before she understood what I was. After that, they forbade it. I practiced anyway.”

Silas didn’t know why the next sentence came out of him, only that it did.

“When we reach Magnolia Reach, you’ll be in the house, not the fields. You’ll assist me. There are books in my study. When your duties are done… you may read them. But you will tell no one.”

Rowan’s eyes widened, and for a moment the practiced mask cracked, revealing something raw and bright underneath.

“Why?” Rowan whispered.

Silas tested his own honesty like it was a blade. “Because you see the world in ways I don’t. And I find that I want to understand.”

He told himself it was curiosity.

He told himself a lot of lies that year.

Magnolia Reach rose out of the Mississippi landscape like a white tooth. Greek columns, clean lines, paint so bright it looked freshly bleached by the sun. Oaks older than the nation draped Spanish moss that swayed like mourning hair.

Eleanor waited on the front portico, posture perfect, smile absent.

“You left without notice,” she said when Silas stepped down. Her voice was calm in the way a pond can be calm right before it swallows you. “I had to explain to the Allisons why you missed their supper.”

“Business,” Silas answered, as if that word could cover any sin.

Eleanor’s gaze slid past him to Rowan.

“And this is?”

“A new house servant,” Silas said. “A personal attendant. My correspondence has been… mismanaged.”

Eleanor studied Rowan the way she studied china for cracks. Something about Rowan’s face made her pause. It wasn’t beauty, not in the narrow way Eleanor used the word. It was a kind of balance. Masculine strength under feminine softness, or perhaps the other way around. The light couldn’t decide where to land.

“This one seems delicate,” Eleanor said, disgust tucked inside politeness. “Better suited for the fields where I wouldn’t have to look at it.”

Silas’s voice hardened. “I’ve assigned the duties.”

Eleanor’s jaw tightened by a fraction. That fraction would, in time, become a blade.

Rowan’s room was a narrow space off Silas’s study: bed, washstand, one small window. It was not kindness. It was strategy. Separate Rowan from the slave quarters, and you separate them from witness and gossip.

Silas laid out the rules like they were a contract.

“Your work is simple. Keep my files. Manage my letters. Clean the study. In the evenings, after the house settles… you’ll come here. We’ll talk about what you’ve read.”

Rowan blinked. “Discuss books, sir?”

“Yes.” Silas hesitated, then added, too quickly, “An educational experiment.”

Rowan’s eyes held him. “And what are you learning, sir?”

Silas didn’t answer, because the answer was already dangerous.

A routine formed, stitched together by secrecy.

At night, oil lamps turned the study gold. Rowan arrived with a book in hand and dust on their fingertips. Sometimes it was Plato. Sometimes Milton. Sometimes a medical text Silas had brought back from town, hidden inside a shipment of account ledgers.

Silas found himself hungry for Rowan’s mind. Rowan’s mind had edges. It asked questions that cut.

One evening, Rowan read from a poem and then looked up. “Do you believe love can exist outside what the world allows?”

Silas laughed softly, but it sounded wrong in his own mouth. “Love exists where it pleases. The world merely punishes it.”

Rowan’s gaze didn’t waver. “And what do you believe you deserve, sir?”

The question struck Silas like a thrown stone. All his life, he’d been told he deserved everything. Land, obedience, heirs, respect. But no one had asked what he deserved in his own skin.

He should have sent Rowan away that night. He should have locked the study and prayed until morning.

Instead, he moved closer, as if drawn by a tide he’d pretended not to hear.

That was the beginning. Not the first touch, not the first sin, but the first surrender.

In the months that followed, what grew between them was not simple. It could not be simple, not with chains in the house and laws in the air.

Silas held power like a weapon even when he didn’t mean to. Rowan knew it. Silas knew it. Every moment of tenderness carried the shadow of ownership.

Sometimes Rowan would go stiff when Silas reached for them, and Silas would pull back as if burned.

“Tell me no,” Silas said once, voice raw. “If you need to.”

Rowan swallowed. “No does not exist for people like me here.”

Silas felt sickness rise in his throat.

Rowan’s eyes sharpened. “But I can tell you this: I am still a person. If you forget that, you become exactly what this place has always made you.”

Silas sat back as though struck.

In the silence, the plantation’s cruelty pressed against the walls like heat.

That night, Silas did not touch Rowan. He handed them a pen instead. “Write,” he said. “Anything. Your thoughts. Your name. Proof you exist on paper like I do.”

Rowan’s fingers trembled as they took it.

Somewhere in the hallway, unseen, Mei-Lin Carter was polishing silver for Eleanor. She listened without being noticed, and she stored the moment away like a coin.

Information was currency.

And Mei-Lin was getting rich.

Years passed with the careful rhythm of a lie maintained.

Eleanor played hostess. Silas played gentleman. Their daughters grew into young women with embroidered futures.

In the shadows, Rowan learned. Medicine, law, philosophy. Silas brought books and pretended they were ledgers. Rowan absorbed them as if learning could grow bones strong enough to carry freedom.

Sometimes Silas would sit with Rowan and speak about the North, about Boston, about people who believed in abolition the way others believed in God.

“I could send you,” Silas said more than once. “Papers. Money. A new name.”

Rowan would look at him and ask quietly, “And what would you do after?”

Silas had no answer that didn’t sound like a tomb.

In the seventh year, the balance shifted. Rowan began to tire easily. Their face grew paler beneath the brown. Their appetite changed. They pressed a hand to their stomach sometimes without meaning to.

Rowan tried to hide it. Secrets were survival.

But secrets, in a household like Magnolia Reach, always leaked through the cracks.

Dr. Jonathan Reeve, the family physician, came one humid morning after Rowan collapsed in the study. Silas carried Rowan to the small room, hands shaking, and shut the door like he could lock the world outside.

Dr. Reeve examined Rowan and turned the color of paper.

“Colonel,” he whispered, “this is… beyond my practice. Rowan appears to be with child.”

Silas’s chest tightened. “How far?”

“Four months,” Reeve said, voice thin. “But… it shouldn’t be possible, given what you described when you purchased them.”

Silas’s mouth went dry.

“It’s possible,” he said, and the confession tasted like blood, “because I made it possible.”

Dr. Reeve’s eyes filled with something like horror and pity braided together.

“This cannot come to term,” he said quickly. “The scandal alone would destroy you. And medically, I cannot predict what childbirth would do to Rowan’s body.”

“No,” Rowan rasped from the bed, eyes wide with fear. “Please. Don’t kill my baby.”

Silas looked between them, torn open. In that moment, he understood what love could be when surrounded by brutality: not a romance, but a wound you refused to let rot.

“Doctor,” Silas said, voice steel-thin, “you will speak of this to no one.”

Outside the door, Eleanor’s shadow paused. She had come for water. She had come because insomnia had been chewing her bones for months.

She heard everything.

And something in her snapped so cleanly it was almost quiet.

That evening, Eleanor entered the study without knocking. The door swung shut behind her with a soft click that sounded like a coffin lid.

She stood before Silas’s desk as the lamplight flickered. Her beauty was sharp, all angles and ice.

“Fourteen years,” she said. “Fourteen years I have been your wife. I bore your daughters. I held this household together while you built your kingdom. And you were in love… with a slave.”

Silas said nothing.

“Not even a slave that fits,” Eleanor continued, voice lowering into something more dangerous than shouting. “A creature that confuses nature the way you confuse decency. And now it carries your child.”

Silas’s hand clenched on the desk. “Do not speak of Rowan like that.”

Eleanor laughed once, short and joyless. “Listen to you. You defend it like a saint defends scripture.”

Silas’s voice cracked. “What do you want?”

“I want the stain removed,” Eleanor said. “Quietly. For our daughters’ sake. For my sake. For the family’s name.”

Silas’s stomach sank.

“I will sell Rowan tomorrow,” Eleanor said. “South. Sugar country. Where bodies break fast and no one asks questions. The child will die before it draws breath. And you… you will live with it.”

Silas stood so abruptly his chair fell backward. “If you do this, I will burn this house to the ground myself.”

Eleanor’s eyes glittered. “Then burn. But you will burn alone. And you’ll take our daughters with you into disgrace. The world will call you pervert, monster, devil. They will call me victim. I will survive it. Will you?”

Silas stared at his wife and understood, with sick clarity, that the only power women like Eleanor held in that world was the power to destroy.

When she left, the air in the room remained poisoned.

Silas sat for hours, hands shaking, mind racing through impossible doors.

Run with Rowan? Where? A white man and a pregnant intersex fugitive slave, crossing a country that hunted such things like sport?

Kill Eleanor? Death, trial, ruin.

Free Rowan publicly? The law would still hunt them. The mob would still come.

In the end, Silas made the only choice that felt like something other than cowardice.

He chose sacrifice.

Near dawn, he woke Rowan gently.

Rowan’s eyes opened, tired and shining.

Silas set a leather pouch on the bed. Gold coins. Heavy. Real.

“I have papers,” Silas whispered, and held out folded documents. “Manumission. Backdated. Enough to confuse anyone long enough for you to vanish north.”

Rowan’s breath hitched. “You can’t.”

“I can,” Silas said, voice breaking. “I should have done it years ago.”

“And you?” Rowan asked. Their hand moved to their stomach, protective. “What happens to you?”

Silas swallowed. “I will tell her you escaped. She will rage, but she will be relieved you’re gone. She will protect her name by burying the rest.”

Rowan’s eyes filled. “I don’t want to leave you.”

Silas leaned in, forehead to Rowan’s. “I know. But this child deserves a chance at life. A chance I can’t give you here.”

Rowan’s tears slid silently.

Silas pressed the papers into their hand like he was handing over his own heart. “Go to New Orleans. Find a Quaker woman at a boardinghouse on Dauphine Street. Say my name. She’ll understand.”

Rowan’s voice turned fierce. “This isn’t love, Silas. This is grief wearing love’s clothing.”

Silas exhaled shakily. “Then let it be grief that saves you.”

They held each other as the house began to stir. Not long, just enough to memorize the warmth.

Then Rowan dressed in plain men’s clothing taken from the quarters. A cap pulled low. A bundle under one arm. Gold hidden in the lining.

Silas walked them to the back door.

In the humid Mississippi dark, even the cicadas sounded like warning.

Rowan paused, eyes on Silas. “If I live,” they whispered, “I will not forget that you tried to see me as human.”

Silas’s throat tightened. “If you live,” he whispered back, “live loudly enough for both of us.”

Rowan vanished into the trees.

Silas stood there until the darkness swallowed the last trace.

Something inside him went quiet in the worst way.

When Eleanor came later, eager to savor Rowan’s capture or absence, she found the small room empty.

She found Silas waiting.

And what happened next became a story told in fragments, because everyone who knew the whole truth had reason to hide it.

The official report said Silas was found dead in Rowan’s bed, dressed in Rowan’s clothing, surrounded by journals. The doctor noted the strange expression on his face, agony braided with impossible ecstasy, and blamed “heart failure” with the kind of medical vagueness that is really money in a coat.

The housekeepers whispered about the message found on the wall, written in blood before someone scrubbed it away.

I DIE LOVING ROWAN. MY ONLY SIN WAS HIDING IT.

Eleanor tried to bury the scandal. She burned pages. Locked drawers. Ordered silence.

But silence is fragile. It shatters when handled by hands that tremble.

Eleanor told her closest friend the truth over tea. The friend told her sister. The sister told her husband. The husband told a man at the courthouse who already hated Silas for politics.

Within two weeks, Natchez was a hive of poison gossip. The authorities came, more curious than righteous. They questioned slaves who had learned long ago that truth can be both blade and shield.

And then Magnolia Reach burned.

Some said it was an accident, a lantern tipped by a trembling maid.

Others said an angry crowd came at night, torches in hand, determined to cleanse the stain from their county.

Mei-Lin Carter knew the truth: Eleanor ordered the fire herself, desperate to erase what paper could not.

But fire, like gossip, spreads beyond intention.

Thirteen men died that night.

An overseer. Two deputies. A cousin who came with a shotgun. Neighbors who wanted spectacle. Men who ran into smoke thinking they were heroes and came out as names carved into stone.

By morning, Magnolia Reach was ash and bones.

The judges refused the case, one after another, claiming “conflict of interest” in voices that sounded like fear. The third judge reportedly vomited after reading excerpts from Silas’s journals.

The county wanted the story buried.

But the North had a way of digging up what the South tried to hide.

Three months after the death, when the scandal had been pushed into whispers again, a manila envelope arrived at the Natchez station. Postmarked Boston.

Inside was a sworn statement written in elegant hand.

Rowan’s handwriting.

Rowan’s truth.

Rowan wrote of Eleanor’s attempt to poison their supper, of Mei-Lin switching the plate at the last moment. Of Eleanor attacking in rage. Of Mei-Lin striking Eleanor with a candlestick not to kill her, but to stop her. Of blood. Fear. Flight.

And then the revelation that turned the case inside out:

Silas had not killed himself out of shame.

He had found Eleanor unconscious and bleeding. He had understood, instantly, what accusation would follow if Rowan and Mei-Lin were caught: attempted murder. Assault on a white woman. A hanging. A spectacle.

So Silas had done something monstrous and holy at once.

He dressed himself in Rowan’s clothing.

He lay in Rowan’s bed.

He drank the poison Eleanor had prepared.

He wrote his confession on the wall.

He became the scandal’s sacrificial lamb so Rowan and Mei-Lin could slip into the dark and live.

“He gave his life for mine,” Rowan wrote. “Not only on that night, but every day he tried to treat me as if I were more than property. I will not pretend our love was clean. Slavery stains everything it touches. But I will say this: in a world built to deny my humanity, he tried, too late, to honor it.”

Rowan wrote that they had reached Boston with help from abolitionists. That Mei-Lin had come too. That the baby was born alive and healthy, held in hands that did not ask what category it fit into before offering warmth.

Rowan did not name the child’s sex. They did not name the child’s future. They only wrote:

“My child will grow in a place where no one has the right to own them. That is the only miracle worth writing down.”

The sheriff showed the letter to Eleanor and asked if she wished to press charges.

Eleanor stared at the pages for a long time. In the end, she shook her head once.

“No,” she said, voice hollow. “Let the dead stay dead.”

She chose silence. Not mercy. Not forgiveness. Self-preservation.

The case was officially closed in January of 1859.

Silas Wainwright’s death remained labeled suicide.

Rowan and Mei-Lin were listed as fugitives.

And the county tried to fold the whole thing into the attic of history, where unpleasant objects are stored until they rot into dust.

But stories don’t rot. They ferment. They grow teeth.

Years later, in abolitionist circles, portions of Silas’s journals surfaced like contraband scripture. A famous orator in the North cited them as proof that slavery corrupted not only bodies but every kind of love, turning desire into violence and tenderness into crime.

Rowan lived in Boston under another name, sometimes dressing in ways that made the world comfortable, sometimes refusing. In small rooms lit by honest winter, they learned what it felt like to breathe without permission.

Mei-Lin found work with abolitionists, her sharp mind finally used for something other than survival. She never spoke publicly of the night she raised the candlestick. But she kept it, wrapped in cloth, like a reminder that sometimes saving a life looks like violence, because the world gives you no gentler tools.

As for Eleanor, she returned to Virginia with her daughters and lived inside the respectable grief of a widow. She never remarried. She never defended Silas. She never forgave.

Yet among her possessions, after her death in 1890, her daughters found one object she had kept hidden for more than thirty years: a single journal from 1851, the early pages worn thin, the margins filled with Eleanor’s handwriting.

At first, the notes were furious. Bitter. Blaming.

Later, the ink changed.

Not kind. Not soft. But altered, like a woman staring too long at a truth she hated until it began to resemble inevitability.

One line, written near the end, trembled across the page:

I wanted him to love me the way he loved the impossible. But perhaps the impossible only looked that way because this world is built wrong.

No one knew if Eleanor wrote it with understanding or simply exhaustion.

Either way, it proved what the county had tried to deny: that the story had not ended with fire.

It had followed them.

In 1885, a memoir appeared in Boston under a pseudonym, printed by a small press brave enough to be hated. The book was banned in most Southern states. Smuggled anyway.

Its title was simple and defiant: NEITHER/NOR.

In the final chapter, the author addressed a man long dead.

“You asked me once what I was,” the writer said. “I told you I was whatever you wanted. That was a survival answer, not a truth. The truth is I was always exactly what I appeared to be: a human being. You saw that before I did. You loved me before I learned to love myself. And you died to give me a life beyond categories.”

The author never confirmed their identity publicly.

But people who knew the old scandal read the words and felt the hair rise on their arms, because some sentences carry the weight of lived pain.

Rowan died in 1902, older than anyone expected a fugitive slave to become. They were buried in Boston soil under a stone that did not mark male or female, only a name and a date, as if insisting that the details belonged to the person, not the world.

Their child grew up to be a physician. A quiet rumor, then a respected one. A doctor known for treating people whose bodies made other doctors nervous. A doctor who, in private notes later found and published decades afterward, wrote:

“Some bodies exist between the words. It is not the body’s job to make the world comfortable. It is the world’s job to become more honest.”

Which is, perhaps, the only ending a story like this deserves.

Not neat.

Not clean.

But human.

And if you ever find yourself tempted to file people into boxes because it makes your mind feel safer, remember Magnolia Reach.

Remember the ash.

Remember the letter from Boston.

Remember that the most terrifying thing in that old world wasn’t a body that defied categories.

It was a society that would rather burn down a house than admit love and humanity can exist where the law insists they must not.

THE END

News

Billionaire Invited the Black Maid As a Joke, But She Showed Up and Shocked Everyone

The Hawthorne Estate sat above Beverly Hills like it had been built to stare down the city, all glass and…

Wife Fakes Her Own Death To Catch Cheating Husband:The Real Shock Comes When She Returns As His Boss

Chicago could make anything feel normal if you let it. It could make a skyline look like a promise, make…

Black Pregnant Maid Rejects $10,000 from Billionaire Mother ~ Showed up in a Ferrari with Triplets

The Hartwell house in Greenwich, Connecticut did not feel like a home. It felt like a museum that had learned…

Single dad was having tea alone—until triplet girls whispered: “Pretend you’re our father”

Ethan Sullivan didn’t mean to look like a man who’d been left behind. But grief had a way of dressing…

“You Got Fat!” Her Ex Mocked Her, Unaware She Was Pregnant With the Mafia Boss’s Son

The latte in Amanda Wells’s hands had been dead for at least an hour, but she kept her fingers curled…

disabled millionaire was humiliated on a blind date… and the waitress made a gesture that changed

Rain didn’t fall in Boston so much as it insisted, tapping its knuckles against glass and stone like a creditor…

End of content

No more pages to load