In the last week of October 1991, the hills of Blackthorn County, Kentucky, wore their autumn like old bruises, purples and rusts darkening under thin fog. The hardwoods along Copperhead Creek had begun to shed, and the water carried leaves the way a mouth carries bitter words it never spits out. People still fished the bends where the current slowed, still washed muddy boots on flat stones, still warned their children not to wander too far past the sycamores. They did all of it the way folks do in places where the past is not a chapter but a neighbor, present even when you don’t answer the door.

Lucian Kincaid was one hundred and one years old when he finally decided to talk.

He lay in the front room of his granddaughter’s house, a small frame home perched above the same creek that had raised him and nearly ruined him. His skin had thinned to paper, and his hands looked like they’d been carved from the root of a tree. Outside, someone had stacked firewood and covered it with a tarp, preparing for winter like it was an ordinary year. But inside, the air carried the quiet urgency of people bracing for a sentence they couldn’t unhear.

His grandchildren sat close, not because the room was cold, but because it felt wrong to let a dying man speak into empty space. The youngest, a college boy with kind eyes, kept holding Lucian’s water cup like it was fragile. The oldest, a nurse in Lexington, watched the pulse in his neck, measuring how much time a truth might have left. Their mother, Lucian’s daughter, stood by the window with her arms crossed, as if she could keep the past from entering by blocking the glass.

Lucian had been a hard man in his prime, quiet the way a locked gate is quiet. He did not weep at funerals. He did not speak much of his childhood. He had never once, in all their lives, told them why he insisted on driving them down to Copperhead Creek every summer, parking by the same bend, and making a crude joke about “waterin’ the ground where a devil ought to be.” They laughed because children laugh when adults give them permission to be vulgar. They laughed because they didn’t know.

That day, his voice came out like gravel, each word scraped loose. “I don’t want to go,” he said, and then he smiled, almost boyish, almost apologetic. “But I reckon I’m done carryin’ it.”

His daughter turned around. “Daddy—”

He lifted one trembling finger, the gesture of a judge and a child at once. “Let me.”

The room stilled. Even the clock seemed to soften its ticking.

“I was fourteen,” Lucian began, staring past the ceiling as if the memory lived up there, nailed to the beams. “And the night Copperhead Creek ran red… it didn’t end the way folks told it. Not the way the papers said. Not the way the old-timers bragged it up to scare strangers.”

His grandchildren leaned in, their faces tightening as if they were listening to thunder roll closer.

“I’m the one who finished it,” Lucian whispered. “I’m the reason they never found Silas Rourke.”

The name landed heavy. In Blackthorn County, some names were spoken like prayers and others like curses. Silas Rourke belonged to the second kind.

Lucian closed his eyes, and when he opened them again, the room around him seemed to drift away, replaced by a different front room, a different October, a different boy holding his breath in fear that had no end.

Back then, Blackthorn County was a world unto itself. The creek cut the land like a boundary drawn by God’s own finger, winding through oak and hickory hills and disappearing into hollers where sunlight arrived late and left early. Roads were narrow ribbons of dirt. People measured distance by ridges instead of miles. Outsiders called the place wild. Folks who lived there called it home, and meant something sharper than comfort when they said it.

On the west side of Copperhead Creek lived the Rourkes.

They owned nearly two thousand acres, the kind of land passed down with pride and gun oil, claimed originally through a war grant that a great-grandfather had earned with a musket and stubbornness. The Rourkes didn’t just have property; they had influence. Silas Rourke ran the only general store for a day’s ride in any direction. The store was where you bought flour, salt, nails, and coffee. It was also where you traded rumors, settled debts, and learned which way the wind was turning in county politics.

But the real currency in Blackthorn County wasn’t money. It was loyalty.

The Rourkes understood that better than any banker. They ran moonshine the way other men ran livestock. Their stills hid deep in laurel thickets, and their whiskey moved along mule trails at night, carried by boys who learned early that silence was a kind of survival. Revenue agents who came nosing around either left discouraged or didn’t leave at all, and nobody asked too many questions about that second category. In the hills, forgetting could be an act of wisdom.

On the east side of the creek lived the Kincaids.

They hadn’t been in Kentucky quite as long, but they carried their own legacy like a sharpened blade. Scotch-Irish stock, folks said, quick to laugh and quicker to fight. They had arrived with copper kettles and a distrust of taxes so deep it might as well have been scripture. Their white whiskey was infamous, the kind that could strip paint and courage in the same swallow. Where the Rourkes held commerce, the Kincaids held the law. A couple of deputies wore the family name, and one cousin, Amos Kincaid, wore a judge’s coat with the same ease he wore a pistol on his belt.

That arrangement had kept them from destroying each other outright.

For years they coexisted in a tense rhythm: occasional scuffles when someone crossed the creek to sell in the wrong territory, a stabbing behind the church, a shooting in a cornfield, then a season of forced quiet while men nursed wounds and women whispered for mercy. Both families attended the same small Baptist church on the ridge during warmer months. They sat on opposite sides like two countries sharing one sanctuary, their hymns rising together but never truly blending.

The church belonged to Reverend Eli Hart.

He was a lean man with a voice that could fill a valley, and he believed, fiercely, that forgiveness wasn’t weakness but work. He preached it like a man swinging an axe, chopping at the roots of hatred one sermon at a time. He’d spent two decades watching boys grow into men who thought pride was worth blood. He’d buried children who died because adults refused to let an insult fade. Each grave hardened him into resolve.

That spring of 1902, Reverend Hart made forgiveness his campaign.

He thundered through verses about loving your enemy, feeding him, giving him drink. He spoke of Christ forgiving nails and spears and betrayal, and he asked his congregation what excuse they thought they had. His wife, Clara, watched the pews while he preached. She saw the way men’s hands hovered near their belts, even in the Lord’s house. She saw the way women’s eyes darted, always counting who sat where. She saw how the hatred sat among them like another parishioner, patient and well-fed.

What neither Reverend Hart nor Clara realized, at first, was that the sudden surge in attendance wasn’t only spiritual.

It had a face.

Her name was Lillian Hart, called Lily by everyone who believed they had the right to soften her. She was sixteen, with a willowy grace that made boys go quiet and girls suddenly remember chores they needed to do elsewhere. She had eyes that seemed to carry a question even when she was smiling. She played the organ well enough to make old ladies dab at their eyes, and she had a habit of listening so closely that people told her things they didn’t mean to admit.

In those hills, beauty wasn’t just admired. It was claimed.

Lily learned that early, the way she learned most things: by watching what happened to girls who didn’t pay attention.

Cole Rourke had been courting her first.

He was eighteen and carried himself like a young man already measuring his future in acres. His hair was dark, his shoulders broad, and his smile had the ease of someone used to getting what he wanted without asking twice. He’d meet her after church, walking her along the ridge where the wildflowers grew, his hand lingering near hers, close enough to promise without touching. He spoke of building a house, of buying her a proper ring, of keeping her safe. Safety sounded like love when you’d grown up hearing gunshots on warm nights.

Wade Kincaid came later.

He was seventeen, all restless energy and quick laughter, a boy who could turn a spiteful remark into a joke and a dull afternoon into an adventure. He didn’t promise her land or protection. He promised her feeling. He’d sneak her notes tucked inside hymnal pages. He’d catch her gaze across the church and grin like they shared a secret against the whole world. When he spoke, he made the future sound like something you could choose instead of endure.

Lily didn’t plan to juggle them. She didn’t think of it as cruelty. In her mind, she was holding two versions of herself, testing which one would survive adulthood. With Cole, she could be Clara Hart’s daughter, respectable, sheltered, married into power. With Wade, she could be her own girl, laughing at the edge of rules and daring the hills to let her go.

But secrets in Blackthorn County didn’t stay buried. They lived on borrowed time, and interest came due fast.

By August, Reverend Hart believed his sermons had softened hearts.

He saw Rourke men nodding when he spoke of mercy. He saw Kincaid women smiling at Clara on the porch. He chose to believe the Holy Spirit was doing what rifles couldn’t: changing minds. And so he proposed something bold, nearly foolish. A potluck. A bean-stringing. A supper at the Hart cabin where both families could sit under one roof, break bread, and see each other as human.

Clara hesitated. She had lived beside hatred long enough to recognize how easily it disguised itself as politeness. But she also trusted Eli’s faith the way she trusted the seasons. If he believed it could work, she wanted to believe too.

Lily, meanwhile, felt the plan like a tightening rope.

Because she knew what nobody else did: that Cole and Wade were not simply rivals in business or blood. They were rivals for her.

The day before the gathering, Lily stood behind the cabin, shelling beans into a basket while the sun bled gold through the trees. Wade approached from the woods, quiet for once, his face serious.

“You been writin’ him, too?” he asked, voice low.

Lily’s fingers froze.

“I seen him lookin’ at you,” Wade continued. “Like you belong to him.”

“He don’t,” Lily said, too quick, too sharp.

Wade’s jaw tightened. “Then tell him.”

Before she could answer, footsteps crunched in the leaves on the other side of the yard. Cole appeared, carrying a sack of flour his mother had sent over, his gaze locking on Wade like a match struck in darkness.

For a moment, time held its breath.

Lily stood between them with beans on her hands and fear in her throat, realizing, too late, that she wasn’t holding two versions of herself. She was holding two fuse ends, and the cabin was about to become the powder keg.

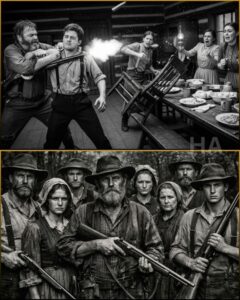

August 16th, 1902, arrived hot and bright, the kind of day that made people believe in good outcomes. Wagons rolled up the ridge road, creaking under families dressed in their best, men in clean shirts, women in aprons, children scrubbed until their ears shone pink. The Harts’ yard filled with voices and cautious laughter. Eli welcomed everyone with open hands and a smile that hid how hard his heart was pounding.

At first, the tension sat on the edges like a stray dog waiting to be kicked.

But then a fiddle started up, and a banjo joined, and the music slipped into the spaces between suspicion. Someone called for a square dance. Dust rose from the yard as boots stomped in rhythm. Older men who’d once threatened each other over whiskey routes found themselves laughing at missed steps. Women sat on the porch stringing beans, swapping stories about births and bad weather, as if gossip could build a bridge where law never had.

Even the moonshine made its rounds.

“Just for scientific purposes,” one man joked, and another answered with a grin, and for a few hours, it looked like Reverend Hart’s dream might become real.

Out back, the teenagers played an old mountain game with a name that made Clara frown and the boys howl with laughter: Shake the Cat. Four boys held a blanket taut while someone tossed a half-startled barn cat onto it, shaking until the animal launched off toward whichever side fate chose. The rules were simple and brutal in the way old games often were: whichever boy the cat ran toward won a kiss from any girl he wanted.

When Lily’s turn came, the air seemed to sharpen.

Cole shouldered into position on one corner of the blanket. Wade shoved in on another. Their hands gripped cloth the way men grip grudges. Lily stood with the cat cradled against her chest, its heart hammering.

“Don’t throw it toward him,” Cole muttered under his breath.

“Don’t you tell her nothin’,” Wade snapped back.

Lily’s throat tightened. She tossed the cat onto the blanket and stepped back as the boys shook. The cat flew up, startled and furious, then leapt off, sprinting in a panic.

It ran straight toward Cole.

The boys erupted. Cole looked at Lily like triumph. He reached for her without asking, and Lily, caught between expectation and fear, let him kiss her cheek. It was quick, possessive, public.

Wade’s face darkened.

The game continued, and the cat, as if tired of being used as an omen, ran toward Wade the next round. Wade didn’t hesitate. He grabbed Lily’s hand and kissed her mouth, not her cheek, not politely, but like a claim.

A hush rippled through the watching teens.

Lily felt the world tilt. She saw, in that instant, what she had been refusing to accept: her secret was no longer a secret. It was a spark thrown into dry brush.

Before either boy could speak, Clara rang the supper bell.

The sound cut through the yard like a blade. Adults began herding kids inside, laughing uneasily, grateful for the distraction of food. Lily followed with her hands trembling, carrying a dish of butter beans into the cabin, trying to breathe as if she hadn’t just lit a match in a room full of gunpowder.

Inside, the table sagged under the weight of a feast: fried chicken, pork chops in gravy, cabbage, sweet potatoes, biscuits steaming in the oven. The smell alone could have softened a lesser hatred. People squeezed shoulder-to-shoulder, Rourkes on one side, Kincaids on the other, the Harts at the ends like anchors trying to hold both shores.

Reverend Hart stood, clearing his throat.

He looked down the table, seeing faces he had prayed over, seeing hands that had held rifles, seeing wives who had buried sons, seeing Lily’s pale expression and not understanding why it frightened him.

“Lord,” he began, voice steady, “we thank You for—”

The punch landed before the blessing could finish.

Wade Kincaid lunged across the table and struck Cole Rourke square in the jaw. The sound was sickening, a crack that made forks clatter and women gasp. Cole’s chair tipped. He hit the floor hard, eyes flashing with humiliation and rage.

For a heartbeat, everyone froze, waiting to see if the moment could still be pulled back from the cliff.

Then Cole’s hand went to his belt.

He came up with a revolver like it was already part of him. He fired once. Twice. The shots were deafening inside the cabin, echoing off walls and bone. Wade staggered, shock registering before pain. Cole kept firing until the chamber clicked empty, Wade collapsing against the table, blood spilling across plates and biscuits like spilled wine at an unholy communion.

Chaos didn’t arrive gradually. It detonated.

Chairs crashed. Women screamed. Men shoved and reached for pistols. In less than half a minute, the cabin became a storm of smoke and violence. Clara was hit as she yanked biscuits from the oven, the shock in her eyes worse than the wound. Reverend Hart threw himself between men shouting for peace, and a bullet caught him in the side, spinning him to the floor. Someone fired a shotgun, the blast ripping through the room and taking a man’s arm clean off, the severed limb dropping like a grotesque offering.

Lily crawled under the table, her dress tearing, her breath coming in panicked sobs she tried to swallow. She watched boots scramble, watched blood drip onto the floorboards inches from her face, watched her father’s Bible slide off the table and land open, pages fluttering as if even scripture wanted to flee.

When the gunfire ran dry, knives came out.

Men who’d run out of ammunition slashed and stabbed, driven by the animal certainty that if you didn’t strike first, you wouldn’t stand at all. Someone yelled a name. Someone cursed God. Someone begged.

By the time it ended, the Harts’ cabin was no longer a house. It was a wound.

Two men lay dead. Six others bled on the floor. The survivors stumbled out into the yard, smoke rising behind them, and the August sun shone down without mercy, bright as judgment. The two clans retreated to their sides of the creek, dragging wounded kin, leaving behind broken dishes, scattered food, and Lily’s childhood.

Reverend Hart lived through the night, but barely.

Clara held his hand and listened to him whisper, over and over, “It wasn’t supposed to be like this.” Lily sat on the porch steps, knees pulled to her chest, staring at the yard where people had danced hours earlier. She realized, with a numb clarity, that her choices had not been private. They had been seeds dropped into soil already soaked with blood.

The next morning, Silas Rourke refused to let the feud cool.

He’d been shot multiple times in the cabin, and the wounds should have kept him in bed. But Silas moved like pain was just another thing to ignore. He gathered men, loaded rifles, and crossed Copperhead Creek into Kincaid territory with vengeance in his eyes and history in his hands.

They hid in the trees near Judge Amos Kincaid’s cabin.

When Amos tried to flee, thinking he could outrun the fury coming for him, bullets tore through him and his brother both. They fell in the yard where their children played. The Rourkes didn’t linger. They vanished back into the woods, leaving grief to do what grief always does in those hills: harden into hate.

For two weeks, the Kincaids scoured the ridges, hunting Silas.

They tracked hoofprints, listened for whispers, questioned strangers on the road. Every creek crossing felt like a possible ambush. Every night carried the threat of fire. Mothers kept children inside. Men slept with guns close enough to breathe on.

The county law finally caught Silas through sheer exhaustion and luck.

They held him in the Blackthorn County courthouse, a squat stone building in town that suddenly felt too small to contain the storm. The sheriff begged citizens to let justice happen, to let the courts do what rifles had failed to do: end it. He spoke of order. He spoke of law.

The Kincaids answered with torches.

They surrounded the courthouse, a ring of men with rifles and firelight, faces twisted in grief and fury. “Turn him over,” they demanded. “Or we’ll burn it down with him inside.”

The sheriff refused, trembling, knowing he was arguing with a tradition older than his badge. Inside, Silas sat on a bench, blood seeping through his shirt, his eyes sharp as nails.

That night, while the courthouse strained under the weight of threat, a small group of Rourkes slipped around back.

They knew the building. They knew the sheriff’s habits. They knew that in those hills, law was only as strong as the men who believed in it. They pried open a rear door, whispered instructions, and led Silas out into darkness.

By dawn, he was gone.

And just like that, the feud ended, at least on paper. The newspapers wrote of the shootout, comparing it to the old Hatfield-McCoy bloodletting, marveling that such violence still existed in America. Folks in Blackthorn County read those headlines with a strange pride and a deeper shame, then folded the papers and used them to start stoves.

Silas Rourke became a legend.

Some said he caught a train north and reinvented himself. Others swore he headed west, married, and died old under a different name. Others believed he never left the hills at all, that he was hidden by kin and would return when the time was right.

Only one boy knew the truth, and that boy grew up carrying it like a stone in his chest.

Lucian Kincaid was fourteen that night.

He had watched his father fall in the chaos at the Hart cabin. He had watched his mother scream until her voice broke. In the weeks after, he watched grown men become shadows, speaking only in plans and threats. Revenge became the language of his household, spoken around the table the way other families spoke of weather.

When Silas escaped, something in Lucian snapped into purpose.

He followed.

Not because anyone told him to. Not because he was brave. Because grief in a boy can feel like a commandment. He tracked Silas’s horse through the woods under moonlight, small hands clutching his father’s pistol so hard his knuckles ached. He stumbled, scraped his knees, swallowed sobs. He kept going because stopping felt like betraying the dead.

Hours later, he found Silas at Copperhead Creek, at a deep bend where the water pooled dark and slow.

Silas was watering his horse, murmuring to it like it was the only creature he trusted. The moon lit the creek like a blade laid flat. Silas looked up when he heard a twig snap, and his eyes narrowed.

“Ain’t you a little thing,” Silas said, voice rough. “Go on home.”

Lucian stepped out, trembling so badly the pistol nearly slipped. “You killed my daddy,” he whispered.

Silas stared at him, and for a moment, something like weariness crossed his face. “Boy,” he said, “your daddy would’ve killed me if he got the chance.”

Lucian’s tears burned. “That don’t fix nothin’.”

Silas took a step forward, hand lifting slowly, not quite reaching for his own weapon, maybe thinking he could talk his way out of a child’s rage. “Listen to me,” he said. “This ain’t your fight.”

But in Lucian’s mind, it was the only fight that mattered.

He fired.

The sound cracked across the creek. Silas jerked back, shock exploding into pain. Lucian fired again, not aiming so much as obeying the hot, terrible force inside him. When Silas fell, the water lapped at the bank like it was trying to hush the world.

Lucian stood there panting, staring at what he had done.

He expected relief. He expected lightning. He expected his father’s ghost to appear and nod approval.

Instead he felt hollow.

He dragged Silas’s body with frantic determination, grunting under the weight of a man far larger than himself. He found a boulder near the bank, heavy enough that even Silas’s strength would have struggled with it, and he tied it around the corpse with rope that cut into his hands. His fingers shook. His stomach heaved. He kept working because stopping meant thinking.

Then he pushed.

Silas slid into the black water with a splash that seemed too small for the act. The creek swallowed him. Leaves spun on the surface. The current shifted, then smoothed, as if nothing had happened.

Lucian fell to his knees on the bank, shaking, his hands sticky with rope burn and blood. He stared at the water until dawn began to pale the sky, and he realized, slowly, that he had not ended violence. He had simply joined it.

The years that followed did not bring peace, only exhaustion.

The Rourkes mourned Silas’s disappearance with bitter confusion, half believing he’d abandoned them, half believing he was still out there. The Kincaids lived with the knowledge that revenge had been taken, but without proof, without a body, without anything that could truly close a wound. Blackthorn County settled into a quieter, colder version of itself.

And Lucian grew up.

He married. He worked. He raised children. He laughed sometimes, even. But the creek never left him. Some nights he woke with the sound of a body hitting water in his ears. Some mornings he stared at his hands and wondered how they could look so ordinary.

He never told anyone.

Not his wife. Not his daughter. Not the sheriff. Not the preacher who replaced Eli Hart after the old man died from complications of that gunshot wound years later, still insisting forgiveness was holy work even as his own faith had been shattered in his home.

Lucian carried his secret through Prohibition, through the Depression, through wars and births and funerals. The feud became a story told in fragments, shifting with each telling. Kids dared each other to go near the Hart cabin ruins. Men at the store swapped rumors about where Silas Rourke had gone. Some swore Copperhead Creek was haunted. Others just said it was deep.

And each summer, Lucian took his grandchildren to that bend.

He made a joke out of it because jokes were easier than confession. He told them to “water Silas’s grave” because turning it into crude ritual made it feel less like a stain on his soul. The children laughed, splashing, not understanding the darkness beneath their giggles. Lucian watched them and felt something twist inside him every time: love tangled with guilt, hope tangled with fear.

Now, in 1991, his lungs rattled with the effort of speaking.

His grandchildren sat silent as he finished the story, their faces pale, their eyes wet not only with shock but with the dawning realization that family history wasn’t always heroic. Sometimes it was just human, and humans were capable of terrible things.

Lucian’s daughter covered her mouth. “All these years,” she whispered, voice breaking. “Why didn’t you tell me?”

Lucian looked at her, and the hardness that had defined him for decades softened into something fragile. “Because I was a boy,” he said. “And boys think they can live with anything if they don’t name it.”

The youngest grandson swallowed hard. “Do you… do you regret it?”

Lucian stared toward the window where Copperhead Creek glimmered faintly through trees. “I regret that I thought killin’ would fix the hurt,” he said. “I regret that I made that creek my confessional instead of the Lord. I regret I taught y’all to laugh at somethin’ that should’ve been laid to rest proper.”

He paused, coughing, Clara Hart’s biscuits and blood and smoke living again behind his eyelids. “But I also know this,” he whispered. “If I hadn’t done it, some grown man would’ve. And they’d have killed ten more after. The hills would’ve fed on it forever.”

The nurse granddaughter reached for his hand, tears slipping down her face. “So what do you want us to do?”

Lucian’s grip tightened, surprisingly strong for a dying man. “Stop takin’ it to the next generation,” he said. “That’s what I want. Don’t you carry my hate. Don’t you carry theirs. Don’t make your children inherit a war they never started.”

His breathing grew shallow. The room leaned closer.

“Find the Rourkes,” Lucian murmured. “Tell ’em the truth. Let it be done.”

Two days later, Lucian Kincaid died as the first frost silvered Blackthorn County’s fields.

The funeral was small. People came who hadn’t visited in years, drawn by respect and curiosity and the quiet gravity of an old man’s passing. Nobody spoke of the confession in the church. Not yet. Truth had its own timing in the mountains.

But after the burial, Lucian’s grandchildren drove down to Copperhead Creek.

They stood at the bend, the water running clear and cold, leaves spinning like small, restless thoughts. The nurse granddaughter knelt and touched the surface, her fingers stinging from the chill.

“We can’t pull him up,” the youngest grandson said softly, staring into the dark depth where the boulder had sunk ninety years ago. “Not now. Not like this.”

“No,” the oldest agreed. “But we can stop pretending.”

They placed a flat stone on the bank and stacked smaller rocks atop it, building a cairn not for Silas Rourke alone, but for everyone the feud had chewed up: Wade Kincaid and Cole Rourke, Reverend Eli Hart and Clara’s ruined hands, the children who grew up watching adults turn grief into ammunition.

Then they did something that would have seemed impossible in 1902.

They drove across the creek.

The Rourke descendants still lived in Blackthorn County, though their land had shrunk over the decades, sold off piece by piece to pay debts and bury dead. They still ran a small store in town, though it was legal now, fluorescent-lit, selling soda and cigarettes instead of moonshine. The name Rourke still drew looks, still carried weight. History doesn’t disappear just because time moves on.

Lucian’s grandchildren walked into that store with hearts hammering, the bell above the door jingling like a warning.

A middle-aged man behind the counter looked up, his eyes narrowing the way mountain eyes do when strangers bring trouble. “Help you?” he asked.

The nurse granddaughter swallowed. “My name’s Kincaid,” she said.

The man’s posture tightened. He glanced toward a back room as if expecting old ghosts to step out armed.

She held up her palms. “We’re not here for that,” she said quickly. “We’re here because our granddaddy died, and he left us somethin’ we can’t keep.”

The man studied her face, and something in him shifted. Wariness, yes, but also the tiredness of someone who has lived under a story too long.

“Go on,” he said, voice rough.

So she told him.

Not with dramatics. Not with vengeance. With a truth that hurt to speak: Silas Rourke hadn’t vanished into legend. He had died that very night in 1902, shot by a fourteen-year-old boy who thought revenge would heal him. His body lay in Copperhead Creek, anchored by stone. The feud had ended, not because one side won, but because a child had done what men couldn’t: made the violence so final it had nowhere left to go.

When she finished, the man’s face had gone pale. He leaned on the counter as if the room had tilted.

“My granddaddy,” he said slowly, “used to swear Silas left us. Said he chose himself over blood.”

The youngest Kincaid shook his head. “He didn’t.”

The Rourke man closed his eyes. For a long moment, he didn’t speak. When he did, his voice cracked. “All them years,” he whispered, “hating a ghost for runnin’… when he was dead the whole time.”

The nurse granddaughter nodded, tears in her own eyes. “We’re sorry,” she said, and the words weren’t an apology for the boy Lucian had been, not exactly. They were sorrow for how human beings can ruin each other and call it honor.

The Rourke man exhaled, a long breath like something leaving his chest. “I don’t know what to do with this,” he admitted.

“Neither do we,” she said honestly. “But we know what we don’t want. We don’t want our kids learnin’ to hate yours over somethin’ that happened before electricity.”

The man stared at them, then looked down at his hands, as if seeing history etched there. Finally, he nodded once, small and decisive.

“Take me to the creek,” he said. “I want to see where he is.”

That afternoon, two families who had spent generations treating Copperhead Creek like a border met on its bank like weary survivors meeting at the end of a war. There were no rifles. No torches. Only a few adults standing awkwardly in the cold, and a cairn of stones catching the pale sun.

The Rourke man knelt, touching the stacked rocks with trembling fingers. He didn’t spit. He didn’t curse. He simply bowed his head, and in that moment, the old legend of Silas Rourke shifted into something smaller and sadder: a man who had bled out under a moonlit sky, unseen, unnamed, swallowed by water.

The nurse granddaughter cleared her throat. “Our granddaddy… he wasn’t proud of it,” she said. “Not at the end.”

The Rourke man nodded slowly, eyes wet. “Maybe that’s the only mercy in it,” he murmured. “That it didn’t feel holy.”

They stood there for a long time, listening to water move over stones, watching leaves drift downstream. The creek didn’t care about their names. It didn’t care about their bloodlines. It carried on, the way time carries on, and that was its quiet lesson: the world keeps moving, but people have to choose whether to drag chains behind them.

When the families finally parted, there was no grand proclamation of peace. No handshake that felt like a movie ending. Just a strange, tender quiet, as if the hills themselves were waiting to see if this truce would hold.

As winter settled into Blackthorn County, the whispers began to change.

Old-timers still talked about the night Copperhead Creek ran red, but now the story wasn’t told with pride. It was told with a kind of grief, a recognition that violence doesn’t make legends so much as it makes orphans. People began visiting the creek bend, not to laugh, not to spit, but to stand for a moment and feel the weight of what happens when pride becomes more valuable than peace.

And somewhere in the hills, Reverend Eli Hart’s sermons finally found their answer, not in a miraculous potluck supper, not in a sudden conversion of hardened men, but in the slow, imperfect choice of descendants who decided that forgiveness could be an ending instead of a weakness.

Because in the end, the feud didn’t die the way feuds like to die, with one side standing over the other.

It died the way a curse dies, when someone finally names it and refuses to pass it down.

THE END

News

All Doctors Gave Up… Billionaire Declared DEAD—Until Poor Maid’s Toddler Slept On Him Overnight

The private wing of St. Gabriel Medical Center had its own kind of silence, the expensive kind, padded and perfumed…

Mafia Boss Arrived Home Unannounced And Saw The Maid With His Triplets — What He Saw Froze Him

Vincent Moretti didn’t announce his return because men like him never did. In his world, surprises kept you breathing. Schedules…

Poor Waitress Shielded An Old Man From Gunmen – Next Day, Mafia Boss Sends 4 Guards To Her Cafe

The gun hovered so close to her chest that she could see the tiny scratch on the barrel, the place…

Her Therapist Calls The Mafia Boss — She Didn’t Trip Someone Smashed Her Ankle

Clara Wynn pressed her palm to the corridor’s paneled wall, not because she needed the support, but because she needed…

Unaware Her Father Was A Secret Trillionaire Who Bought His Company, Husband Signs Divorce Papers On

The divorce papers landed on the blanket like an insult dressed in linen. Not tossed, not dropped, not even hurried,…

She Got in the Wrong Car on Christmas Eve, Mafia Boss Locked the Doors and said ‘You’re Not Leaving”

Emma Hart got into the wrong car at 11:47 p.m. on Christmas Eve with a dead phone, a discount dress,…

End of content

No more pages to load