They found them the next morning because the storm finally allowed the living to remember the dead existed.

Ashford County had been buried under white all night. The kind of snow that didn’t drift so much as decide, stacking itself against doors and fences like a verdict. By dawn on December 25th, 1885, the wind surrendered to a thin, brittle quiet. Smoke rose from chimneys again. Horses snorted in frosted barns. Men with shovel-blisters carved trenches between houses and the road, and in the middle of all that ordinary survival, someone noticed one thing that didn’t fit.

No smoke rose from Grayson Manor.

Grayson Manor sat on its hill like an old bruise in the landscape, dark brick and timber staring down at the valley. It was only three miles from town, but the pines and fields between made it feel farther, like the house lived on a different calendar. Most families in Ashford had a story about it. A cousin who’d delivered flour there and never went again. A carpenter who swore the dining room was colder than the cellar. A preacher who insisted the Graysons gave generous donations because even the wealthy feared judgment.

Sheriff Elias Whitcomb rode up with two deputies and four volunteers, more for the comfort of numbers than for any lawful necessity. The path up the hill had been churned into ice, the wagon wheels cracking it like thin glass. The house stood unmoving in the morning glare, every window blind with frost.

They knocked until their knuckles went numb.

No answer.

“Maybe they went to the mill,” a volunteer muttered, but his voice held no belief. Christmas morning at the mill was unthinkable. The Graysons were proud in the way granite is proud.

Sheriff Whitcomb tried the front door. It didn’t budge. He leaned his shoulder into it anyway, then stepped back, frowning at the iron lock.

“Locked from the inside,” Deputy Crane said, as if stating it might keep it from being true.

They moved along the porch, peering into windows, wiping circles clear with glove palms. Candle stubs. Curtains drawn. A tree in the corner of the parlor, dulled by frost on the glass. Nothing stirred.

Then the sheriff’s gaze caught on the dining room window. The long one, the one that looked like a mouth.

He scraped away the frost.

And there they were.

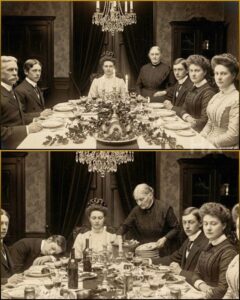

Six Graysons and the old housekeeper, seated around a table set for Christmas. Their heads bowed as if in prayer, hands folded or gently touching the place settings. The goose sat in the center, browned and carved but untouched, the gravy boat full, the bread still whole. The candles had burned down to shallow puddles of wax, but the wicks were black.

Every face was pale in that peculiar way that made the living want to apologize for breathing.

No blood. No knife. No sign of struggle. Just a terrible stillness, arranged so neatly it felt deliberate.

Whitcomb didn’t speak for a moment. He was a practical man, and practicality hates a mystery it can’t bully into submission.

“Break it,” he said finally.

A volunteer lifted an axe. The first strike splintered the doorframe like dry bone. The second strike forced the bolt.

Cold air rolled out of the manor, not the normal winter cold, but a colder cold, a kind that seemed to carry memory.

They entered single file with lanterns held high. Their boots left wet prints on the entry rug. The house smelled faintly of pine, spiced wine, and something like extinguished smoke.

The dining room door stood open.

They stepped into a scene that looked, at first glance, like a painting someone had forgotten to finish.

Thomas Grayson sat at the head of the table, posture straight, hands resting near his plate as though he’d been interrupted mid-sentence. Eleanor sat at the opposite end, her fingers still curled around the edge of a napkin. Samuel’s eyes were closed, his jaw set like a man determined to keep a promise. Margaret’s hand lay on a small stack of pages beside her plate, ink smeared as if she’d been writing until her pen slipped from her grip. Catherine sat stiffly, chin raised, almost defiant even in death. William leaned slightly toward his sister, as if seeking warmth that no longer existed. Mrs. Brennan, the housekeeper, sat between Eleanor and William, a rosary looped around her fingers.

On Thomas’s plate lay a single piece of bread, uneaten. Beside it, a glass of mulled wine.

Whitcomb leaned closer, then froze.

In the center of the table, between the goose and the candles, lay a leather-bound journal opened to a page with one line written in a steady hand.

If you are reading this, then we have done what we should have done long ago.

The sheriff swallowed.

The windows rattled softly, even though the wind had died hours ago.

And the grandfather clock in the hall, which should not have been running at all in that cold house, ticked once. Then again.

The night before, Thomas Grayson had felt the storm in his bones long before the first snowflake touched the hill.

At fifty-two, he’d learned the language of machines and ledgers, of mill schedules and cotton shipments. He could tell by the smell of river water whether the wheelhouse would freeze by morning. He could hear a loom’s complaint and know which gear needed oil.

But this was different.

This was the sensation of being watched by something patient enough to wait out generations.

He stood in his study on the second floor, fingers tight on the windowsill, staring into the gray afternoon as it gathered itself into a blizzard. The valley below was already softening into white, fields losing their edges, the road from town becoming a pale thread.

Behind him, the house made its usual noises: the settling of timber, the sigh of a draft, the distant clatter of pans from the kitchen. Familiar sounds. Comfort sounds.

And yet his stomach stayed knotted, as if familiarity itself had become suspicious.

“Thomas.” Eleanor’s voice found him gently, the way it always did when she was trying not to startle him.

He turned.

She stood in the doorway in a green dress that made her eyes look brighter than they had any right to be in December. Her dark hair was pinned neatly, her hands dusted with flour from the pastry dough she’d been rolling downstairs. She was forty-eight, and she moved through the world with a practiced grace that had once made Thomas feel like he’d married light itself.

Tonight, the light looked worried.

“The children are asking for you,” she said. “Samuel wants to know if he should bring in more firewood.”

“Yes.” Thomas forced a smile that came out like a bad imitation of himself. “Tell him yes. Bring in enough for the night.”

Eleanor hesitated, then stepped in and closed the door behind her. “You haven’t slept,” she said quietly. “Not really.”

Thomas tried to shrug, but it felt like his shoulders were full of stones. “The mill. Father’s estate. Everything piles up.”

“That’s not it.” She didn’t accuse him. She simply named the truth as if it deserved the courtesy of being spoken aloud. “You’ve been… listening. To the house.”

His throat tightened.

In the past month, he’d woken with the impression of footsteps above him when no one was moving. He’d caught the faintest smell of damp rope in hallways that had never known rope. He’d walked into the dining room and felt a cold spot so sharp it made his teeth ache, like the air itself had been bruised.

Worst of all were the dreams. His grandfather Nathaniel, pale and furious, standing in candlelight, pointing at him with a hand that looked both accusing and pleading. A woman in a noose, her face hollowed by time, watching from behind his reflection.

Thomas had told himself it was grief. He’d buried his father in the summer, watched the earth cover a man who had never once admitted fear aloud. Afterward, Thomas had found the journals.

He hadn’t gone looking. That was the part that haunted him. The loose panel in the study wall had practically offered itself up, as if the house wanted him to find what was hidden.

Dozens of leather-bound books. Neat handwriting. Dates. Names. Confessions that read like a family’s bloodline had learned to write only in guilt.

He had read them by lamplight until his eyes burned and his hands shook.

And now it was Christmas Eve.

Fifty years since Nathaniel’s death.

Thomas took Eleanor’s flour-dusted hand and held it a moment too long. “We’ll have dinner,” he said, more to convince himself than to answer her. “We’ll sing. We’ll be a family. For one night.”

Eleanor searched his face. “And after?”

Thomas didn’t answer.

Downstairs, Grayson Manor performed Christmas with the stubbornness of tradition. The parlor smelled of pine and wax. Evergreen boughs were pinned along banisters. A small tree glittered with candles and paper stars Catherine had cut with careful precision.

Samuel, twenty-four and already wearing responsibility like a tailored coat, carried wood from the shed in thick armloads. He looked like Thomas had looked at that age, tall and solid, but his eyes were sharper, more modern, as if Harvard had taught him to question what the Grayson name demanded.

Margaret, twenty-two and sunlight on legs, arranged holly over the doorway and hummed a carol under her breath. She was engaged to a Boston merchant’s son and had begun to talk about spring weddings as if the world could be planned into obedience.

Catherine, sixteen, quiet and capable, hung decorations with the seriousness of a person who believed the smallest details held the largest consequences. William, fourteen, bounced from room to room like he had springs for bones, bursting with questions and hope.

In the kitchen, Eleanor and Mrs. Bridget Brennan worked in practiced harmony.

Mrs. Brennan had served the Graysons for thirty years. Her hands were gnarled, her knuckles swollen with arthritis, but she could still chop vegetables with the speed of someone who had spent a lifetime feeding other people’s celebrations.

Steam rose from the iron stove. Goose fat sizzled. Bread browned. Spices warmed the air until it almost felt like safety.

Almost.

Eleanor glanced up from the pastry and noticed Mrs. Brennan had stopped chopping.

The old woman stared toward the kitchen doorway as if the shadows beyond had begun to move in a language only she understood.

“You’re quiet today,” Eleanor said, keeping her voice gentle. “Is something troubling you?”

Mrs. Brennan blinked, as if returning from far away. “Old superstitions,” she said, but her tone held no humor. “My mother used to say when the snow falls silent and the birds go quiet, it means something is waiting.”

“Waiting for what?”

Mrs. Brennan swallowed. “She never said. She just made us hang iron horseshoes over the doors on such nights.”

Eleanor tried to laugh it away, but the sound didn’t land. “It’s just the storm. It makes everything feel… close.”

Mrs. Brennan’s eyes did not soften. “This house feels heavier today,” she whispered. “Like it’s remembering.”

By late afternoon, the storm arrived properly. Snow stopped drifting and began attacking. Wind threw itself against shutters until the whole manor seemed to shudder in protest. Samuel secured windows. Thomas checked locks. Margaret lit candles early, as if light could bargain with darkness.

At six, the family gathered in the parlor. The fire roared. Thomas poured mulled wine for the adults, cider for the younger ones. For a small stretch of time, the storm became background music.

Margaret played the piano, her fingers bright and sure. William conducted an invisible orchestra, earning a rare laugh from Catherine. Eleanor leaned her head on Thomas’s shoulder, and Thomas let himself pretend his fear was an overgrown shadow that would shrink if ignored.

Then the hall clock chimed seven.

The temperature dropped so suddenly Thomas’s breath turned white.

The fire flickered, dimming as if something had passed between flame and air.

Margaret struck a wrong note, and the discord hung in the room like a warning bell.

Samuel rose. “Draft?” he asked, but his voice lacked confidence.

Thomas’s gaze fixed on the mirror above the mantel.

In the glass, behind his own reflection, a pale face appeared for a heartbeat. Gaunt. Hollow-eyed. Familiar in the way nightmares become familiar.

Thomas blinked hard. The reflection vanished.

Eleanor’s hand tightened on his. “Thomas,” she whispered. “What is it?”

He lied automatically, because lies were what Graysons had always used to hold their world together.

“Nothing,” he said. “Just tired.”

When Mrs. Brennan appeared in the doorway to announce dinner, her face looked as if she’d seen the same mirror.

The dining room was set with the family’s finest china and silver, candles glowing in ornate holders. The goose waited like a centerpiece meant to prove wealth could taste like warmth.

But the room felt wrong, not because of any visible detail, but because the air itself seemed to hesitate, as if deciding what to do with them.

They took their seats.

Thomas at the head.

Eleanor at the foot.

Children between them, as always.

Mrs. Brennan moved like a shadow, ladling soup into porcelain bowls.

Thomas bowed his head to pray, but he felt like he was speaking into a room that already contained too many listeners.

They ate in near silence. Snow pressed against the windows like pale hands seeking entry. The storm’s howl seeped into every pause between words.

Thomas pushed soup around his bowl without tasting it. He watched his children instead, memorizing them.

Samuel’s serious focus.

Margaret’s brave little smiles.

Catherine’s careful stillness.

William’s restless hope.

He realized with a strange clarity that fear did not come from thinking you might die. Fear came from looking at people you loved and imagining the world without them.

“Father,” Samuel began, trying to tug conversation toward something solid. “I’ve been meaning to discuss the mill. Professor Hutchins says—”

Thomas heard himself interrupt. “There’s something I need to tell you all.”

The sentence landed heavy. Eleanor’s fork stopped halfway to her mouth.

Samuel’s brows knit. “Tell us what?”

Thomas took a breath. It felt like breathing against ice.

“It’s about my grandfather,” he said. “Nathaniel. And his father. And his father’s father.”

Margaret’s face tightened with concern. Catherine’s lips parted slightly, as if she’d sensed this story waiting.

Thomas’s voice dropped. “Nathaniel died in this room on Christmas Eve, 1835. Exactly fifty years ago tonight.”

William gave a nervous laugh. “Well that’s… dramatic, isn’t it?”

Thomas didn’t smile.

“He didn’t die of fever,” Thomas said. “He died of poison. His wife, Abigail, put it in his wine.”

Eleanor’s hand flew to her throat.

Samuel leaned forward, lawyer’s mind already sorting facts. “Why?”

Thomas looked at the candles. Their flames wavered, though no draft touched them.

“Because fifty years before that, in 1785, Nathaniel’s father Josiah killed his own brother at this very table over a business dispute. Stabbed him. Buried him in the woods behind the property.”

Silence thickened.

“Abigail discovered proof,” Thomas continued. “Letters. Papers. She begged Nathaniel to report it. He refused. He said the family name mattered more than justice for a man dead fifty years.”

Margaret’s eyes filled. Catherine went pale.

Samuel’s jaw tightened. “And you’re telling us this now because…”

Thomas met his son’s gaze. “Because my father told me on his deathbed there’s a pattern.”

His voice shook at last, betraying what pride had tried to hide.

“Every fifty years,” Thomas said. “Violence. On Christmas Eve. Inside these walls.”

He looked around the table at the faces he loved.

“And now it’s 1885.”

The hall clock ticked, and the sound felt like a finger tapping on a coffin lid.

William’s bravado collapsed. “That’s superstition,” he said too quickly. “We’re not living in Salem anymore.”

Thomas swallowed. “Nathaniel kept journals,” he said. “He traced it back farther. To 1742. A Thomas Grayson who went mad and murdered his wife and children. And further still, to 1692.”

Margaret whispered, “The witch trial years.”

Thomas nodded. “Edmund Grayson, our ancestor, served as a judge. He sentenced twelve people to death. One of them, a woman named Mercy Blackwood, cursed him before she was hanged.”

The candles flickered again.

Mrs. Brennan’s ladle clanged against a bowl. Her knuckles whitened.

“She said Grayson blood would be poisoned,” Thomas continued, “and the curse would manifest in full force, returning in cycles, demanding payment for the innocent destroyed.”

Samuel pushed back slightly, refusing to let fear take the chair at the table. “Curses aren’t contracts,” he said. “They’re stories people tell when they don’t want to admit human cruelty.”

Thomas stared at him with exhausted honesty. “Then explain why every firstborn male in this family has died violently.”

Eleanor’s voice trembled. “Thomas. Stop. You’re frightening them.”

Thomas’s eyes burned. “No more secrets,” he said, and it was less a decision than a surrender. “Not tonight.”

A tremendous crash erupted from the front of the house.

The entire manor shuddered.

William yelped. Margaret stood so fast her chair nearly fell.

Samuel bolted from the dining room. The others followed into the entry hall, where the front door lay torn from its hinges, shattered by wind. Snow poured in like an invading army, filling the hallway with a blinding swirl.

Thomas and Samuel shoved a heavy bench into place, then hauled furniture and drapes to barricade the opening. Their breath came out in frantic white bursts. Eleanor tried to help, her dress dragging in snow.

When they finally sealed the gap enough to slow the storm’s entry, they stood panting in a hallway that looked suddenly smaller, as if the house had drawn in around them.

They tried the other doors.

Back entrance: frozen shut, lock seized with ice.

Kitchen door: immovable.

Even the cellar bulkhead resisted, as though something on the other side held it.

They were sealed inside.

At eight, the grandfather clock chimed with ruthless calm.

Thomas looked at his family and felt something cold settle into his chest: not fear anymore, but certainty.

The house had them now.

They retreated to the parlor, huddling close to the fire that no longer felt quite warm. Mrs. Brennan rocked in her chair, lips moving in prayer.

It was Catherine who spoke first, her voice small but steady. “I felt it earlier,” she admitted. “Like someone was standing behind me while I decorated. I turned and nothing was there.”

Margaret’s voice cracked. “The portraits. I swear their eyes followed me all day.”

Samuel tried to hold the line of reason. “We’re frightened and trapped,” he said. “That’s enough to make any shadow look like a ghost.”

Then Catherine’s gaze snapped to the corner of the room.

Her face drained of color.

Everyone turned.

In the far corner, where the firelight barely reached, stood a woman.

Not fully solid, not fully air.

Translucent like mist.

Dressed in an older style, hair pinned back, neck bruised by the clear shape of a rope.

Her eyes were hollow pits that still managed to burn with hatred.

Eleanor screamed.

William buried his face in Margaret’s shoulder.

Samuel grabbed the fireplace poker, holding it like a weapon even though it felt foolish.

The woman raised one skeletal hand and pointed directly at Thomas.

The room’s temperature plunged. Frost crept along the window edges.

Her lips moved, soundless.

And yet they all heard her voice anyway, not in the air, but in their minds.

You carry the blood.

The woman vanished as quickly as she’d appeared, leaving only the sense of being watched by something that did not blink.

Mrs. Brennan made a sound like a sob. “It’s her,” she whispered. “Mercy Blackwood.”

Thomas’s hands shook. “The journals described her exactly,” he said.

Samuel’s voice went thin. “Then it’s not imagination.”

The hall clock ticked.

Tick.

Tick.

Like a patient executioner.

They spent the next hour clinging together, listening to the house rearrange itself with sounds that should not have existed. Doors slamming in empty rooms. A distant crash of breaking china. Faint whispers in the walls, just below understanding.

Thomas fetched Nathaniel’s journals from his study and spread them on the parlor table as if paper could shield them from the unseen.

He read by candlelight, voice hoarse. “Nathaniel tried to break the curse. He tried rituals. Prayers. He believed the house itself held the guilt.”

Samuel paced. “We don’t have time for theories,” he snapped, then softened when Eleanor flinched. “Sorry. Mother. We need something we can do.”

Thomas turned a page and froze.

“There,” he said. “He wrote about one thing that might matter.”

He traced the passage with his finger.

“Not containment,” Thomas read aloud, “but confession. Full disclosure of every crime. Bring it into light. Accept responsibility. Offer atonement.”

Margaret’s voice came out raw. “Confess for sins we didn’t commit?”

Catherine spoke quietly, surprising them. “We live off the wealth those sins built. We live in the house their cruelty paid for. Maybe pretending that means nothing is its own kind of crime.”

Samuel’s mouth opened, then closed. His certainty wavered.

Eleanor stood, straightening her shoulders like she was deciding what kind of woman she would be in the last hours of her life. “Tell us what to do,” she said to Thomas. “No more hiding.”

Thomas swallowed. “Nathaniel said the family must gather where the first sin in this cycle was committed,” he said. “The dining room. We must speak the truth aloud and offer… a price equal to the harm inflicted.”

William began to cry quietly, furious at his own fear. “I don’t want to die,” he whispered.

Margaret pulled him close. “You’re not going to,” she lied, because sometimes love lies when it has no other tool.

The temperature plunged again.

The fire went out.

Not slowly. Not naturally.

One moment there was flame, the next there was only blackness and a thin ribbon of smoke rising like a mockery.

In the darkness, laughter slid through the room, cold and delighted.

Mrs. Brennan whispered, “She’s playing with us.”

Samuel struck a match with shaking hands and relit candles, their small flames making the room look even more helpless.

“We’re doing the confession,” he said. “Now. Together.”

The walk to the dining room felt longer than it should have. Hallways seemed to stretch, shadows thickening in corners as if gathering to watch. The house shifted around them in subtle ways, like a living thing adjusting its grip.

When they entered the dining room, the table had changed.

The food was rotting.

The goose was coated in green mold. Vegetables had shriveled. The smell of decay pressed against their throats.

And where there had been seven place settings, there were now thirteen.

Extra chairs. Extra plates. Extra silverware.

As if the dead had been invited.

“Stand around the table,” Thomas said, voice barely steady. “Join hands.”

They formed a circle.

Thomas at the head where he’d sat at dinner.

Eleanor opposite.

Children and Mrs. Brennan filling the spaces between.

When their hands linked, something surged through the room, not warmth, but connection. A strange pulling sensation, like the blood in their veins remembered every Grayson who had ever lived and decided to speak for them.

Thomas began.

“I am Thomas Jonathan Grayson,” he said. “And I acknowledge the sins of my ancestors. I acknowledge that my comfort was built on violence and injustice.”

As he spoke, the air shimmered.

Figures appeared around the table, translucent and wavering. Men and women in clothing from different eras, all bearing that unmistakable family resemblance: the same cheekbones, the same sharp brows, the same stubborn mouths.

Ghosts of Graysons past.

Eleanor squeezed Thomas’s hand and continued, voice trembling but clear. “I am Eleanor Catherine Grayson. I married into this family ignorant of its history, but I benefited anyway. I lived in this house. I raised my children on the fruits of evil. I acknowledge it.”

Samuel spoke next, jaw clenched. “I am Samuel Grayson. I believed I could inherit without paying. I believed education could make blood irrelevant. I was wrong.”

Margaret’s tears ran down her cheeks. “I am Margaret Grayson. I wanted love and spring weddings and songs, and I never asked what paid for the music.”

Catherine’s voice was quiet but sharp as a needle. “I am Catherine Grayson. I felt the wrongness and I still decorated the table.”

William’s voice shook. “I am William Grayson. I wanted gifts.”

Mrs. Brennan’s knees nearly buckled, but she held on. “I am Bridget Brennan,” she sobbed. “And I stayed. I saw the shadows and I stayed.”

The room brightened, though no flame fed it.

Behind Thomas, something colder than winter took shape.

Mercy Blackwood stood at his shoulder, her hands resting lightly as if she were claiming him the way a judge claims a sentence.

Her expression was rage worn thin by centuries.

And when she spoke, it was with a weary clarity that made Eleanor’s heart ache as much as it terrified her.

“For two hundred years,” Mercy said, “I waited for you to name what you are.”

Thomas swallowed, forcing himself to look at her. “We cannot undo what was done,” he said. “We cannot bring back the dead. But we will not hide anymore. We will end this cycle.”

Mercy’s hollow eyes moved around the circle. “The curse was never mine to place,” she said. “It grew from your family’s silence. Guilt festers when it is buried.”

Samuel’s voice broke. “Then tell us how to stop it.”

Mercy’s gaze fixed on him. “You will give away what was built on suffering,” she said. “You will return the mill’s wealth to those who labored for it. You will tell the truth, not as entertainment, but as warning.”

Margaret nodded violently. “I will write it all. Every word.”

Mercy’s expression softened by a fraction, like an old bruise finally pressed and released. “Confession is a beginning,” she said. “But debt requires payment.”

Thomas’s chest tightened. “You want blood.”

Mercy tilted her head. “Not blood spilled by hands,” she said. “Blood ended by choice.”

The room grew colder.

“The Grayson name will not walk out of this house tonight,” Mercy said. “If it does, the cycle returns. The house will remember. The silence will regrow.”

Eleanor gasped. “No.”

Mercy looked at her, and for a moment her hatred looked almost like grief. “Your children will live if you choose differently,” she said, then corrected herself with cruel honesty. “They will live in spirit if you end what your bloodline began.”

Thomas felt something shatter in him, not from fear, but from understanding.

This was what the pattern had always been: not random violence, but payment collected from pride.

Samuel’s hand tightened around Catherine’s.

Margaret’s sob turned into a breathless laugh of disbelief. “You’re saying…” she whispered. “We die so no one else has to.”

Mercy’s voice lowered. “You die so the house can no longer feed,” she said. “You die so the name ends, and the wealth returns to the world it stole from.”

Thomas looked at his family.

He saw Samuel’s anger and courage.

Margaret’s tenderness trembling into resolve.

Catherine’s fierce honesty.

William’s frightened, innocent face, suddenly forced to learn what adulthood really costs.

Eleanor’s eyes, steady on him, as if saying: If we must, we must together.

And Thomas realized the most unbearable truth of all: his father hadn’t begged him to leave the house because leaving would save them. His father had begged him to leave because staying would demand something Thomas never believed he could give.

But now, with his family’s hands in his, Thomas knew he could.

Not because he was brave.

Because he loved them enough to choose a love that outlived them.

Thomas spoke, voice rough. “If we do this… if we accept… will the innocents be free?”

Mercy’s eyes flickered. “My descendants,” she said. “The poor in your valley. The workers whose backs built your comfort. Free them with what you have left.”

Samuel’s voice steadied. “We can do that,” he said. “Tonight.”

Mercy nodded once. “Then do it. And when midnight comes, you will leave this world with the truth in your mouth instead of poison.”

Thomas’s lips trembled. “Abigail poisoned Nathaniel.”

Mercy’s gaze sharpened. “Abigail acted alone, hiding truth behind violence,” she said. “You will act together, giving truth away. That is the difference between vengeance and redemption.”

The ghosts around the table leaned closer, hungry for what came next.

And Thomas realized Mercy had not brought them here to slaughter them like animals.

She had brought them here to see whether Graysons could finally choose something other than pride.

They had less than two hours before midnight.

Samuel moved first, because it was easier to act than to feel. He went to his father’s study and dragged out the iron safe containing deeds, contracts, bank notes, and the careful paperwork that made wealth feel legitimate.

Margaret gathered ink, paper, and a sealing wax stamp. Her hands shook, but her mind turned sharp. If the truth had to survive, it needed words that couldn’t be denied.

Eleanor wrote letters to the church, the school, the mill foreman, and Sheriff Whitcomb. She wrote like a woman sewing a lifeline out of sentences.

Thomas dictated and signed. His name looked strange on paper now, like a signature belonging to a man already gone.

They worked at the dining table, the rotten feast sitting untouched as if mocking time itself. Occasionally the air shifted, and Thomas felt unseen faces watching from the shadows.

Catherine stayed close to William, her arm around his shoulders. She whispered to him about sunlight and spring and the idea that a person could do one good thing so big it changed the shape of the world.

William’s tears dried into quiet, exhausted acceptance.

Mrs. Brennan hovered near the doorway, wringing her hands. “There’s a root cellar behind the house,” she whispered. “My mother told me. It’s built into the hill. If someone has to live to carry those papers…”

Eleanor looked up sharply. “Someone does,” she said.

Thomas understood her immediately, and the relief that flickered in him felt shameful. He didn’t want to leave any of them behind. But a humane ending demanded a witness. A living hand to deliver the justice the dead had earned.

Samuel turned to Mrs. Brennan. “You will take them,” he said. “All of them. The deeds, the letters, Margaret’s account. You will go to town when the storm breaks enough for you to move.”

Mrs. Brennan’s face crumpled. “I can’t leave you.”

Eleanor walked to her and took her hands. “You can,” Eleanor said softly. “And you must. We have taken enough from the world. Tonight we give something back, even if it costs us.”

Margaret pressed the first pages of her account into Mrs. Brennan’s palms, ink still wet. “If they call us monsters,” she whispered, “let them at least call us honest ones.”

Mrs. Brennan sobbed, but nodded.

They prepared her like a soldier being sent away from a battlefield she didn’t choose. Wrapped her in a heavy shawl. Gave her a lantern and the iron key.

Thomas pressed a final letter into her pocket, sealed with wax. “For the sheriff,” he said. “Tell him not to force the door. Tell him… tell him we chose this.”

Mrs. Brennan looked at the family seated around the table, their faces lit by candlelight that no longer felt festive. “May God receive you,” she whispered.

“And may He forgive what we didn’t,” Thomas replied.

She left through the kitchen, down the narrow corridor, to the back of the house where the cellar door was hidden beneath snow and ivy.

When it opened, cold air poured in as if the night had been holding its breath.

Mrs. Brennan hesitated on the threshold and looked back once.

In the dining room window, she thought she saw figures standing behind the family, shoulder to shoulder, pale and waiting.

Then the door shut.

The house swallowed the sound.

With Mrs. Brennan gone, the manor grew quieter, as if satisfied.

They returned to the dining table.

They did not eat. Hunger felt like a childish request.

Instead, they spoke.

Not about curses or ghosts.

About things they had never said aloud because life always pretends there will be more time later.

Thomas told Samuel he had been proud of him even when he’d acted stern.

Samuel admitted he’d been angry at his father’s distance because he’d mistaken fear for coldness.

Margaret confessed she’d always been afraid her brightness was foolish, that the world would punish her for believing in joy.

Catherine admitted she sometimes hated being the responsible one, but she loved William fiercely enough to carry that burden anyway.

William whispered that he wished he’d been kinder to the stable boy last week, and Eleanor kissed his forehead and told him kindness is a habit, and habits can be started at any moment.

Outside, the storm softened into flurries.

Inside, the clock kept walking toward midnight with the calm arrogance of time.

At eleven-forty-five, the candles guttered low, though no one touched them.

A pressure filled the room, heavy as deep water.

The air shimmered.

The extra chairs around the table seemed less empty now.

Margaret’s pages lay stacked beside her plate, sealed and ready to be carried into the world by someone with warm blood.

Samuel reached across the table and took his father’s hand.

Thomas looked around at his family.

He expected terror.

Instead, he felt something like peace, sharp-edged and sorrowful.

Because for the first time in his life, he was not hiding.

The house, he realized, had never been hungry for flesh.

It had been hungry for silence.

And tonight, silence had been starved.

The grandfather clock began to chime.

One.

Two.

The sound spread through the manor like ripples.

At the sixth chime, Eleanor began to pray, not for survival, but for the courage to meet what came with dignity.

At the ninth chime, Thomas heard whispers in the walls, not mocking this time, but listening.

At the eleventh chime, the dining room temperature dropped again, but it didn’t feel like punishment.

It felt like a door opening.

At the twelfth chime, the candle flames lifted as if pulled upward by invisible breath.

Mercy Blackwood appeared at the head of the table beside Thomas, her face no longer twisted with hatred.

Just tired.

So very tired.

She looked at them as if counting, as if making sure every Grayson present had chosen.

And then she spoke, softly enough that even the dead had to lean in.

“You do not get to keep what was built on bones,” Mercy said, her voice like snow falling on graves. “But you do get to decide what you become at the end.”

Thomas squeezed Eleanor’s hand, and for the first time the house felt less like a trap and more like a confession booth.

One unforgettable line settled into the room, heavy and holy: “Let the name die, so the world can live.”

The air warmed for one heartbeat, as if mercy itself had exhaled, and then the light went white.

The volunteers later swore there was no scream in the manor that night.

Only a hush so complete it sounded like forgiveness.

Mrs. Brennan reached town just before dawn, staggering through knee-deep snow, clutching papers to her chest as if they were a child.

Her lantern was nearly dead. Her hands were raw from cold.

But she carried what the Graysons had left behind: truth, and the machinery of justice that truth required.

Sheriff Whitcomb listened with a face that grew older with every word.

He read Thomas’s letter.

He read Eleanor’s.

He read Margaret’s account until his eyes blurred.

When the town finally fought its way up to the manor, they found what Thomas had promised they would find.

A family seated around a table, food untouched, doors locked from within, faces calm as if sleep had simply chosen an unfortunate shape.

People whispered about poison, about spirits, about madness.

The doctor found no clear cause. No bruises. No signs of struggle.

Only that same strange stillness, arranged with intention.

In the weeks that followed, the mill’s ownership transferred to a trust that placed workers on the board. The Grayson accounts were drained into churches, schools, and a hospital fund that would eventually build a small clinic on the edge of town. The land behind the manor was deeded to the Blackwood line, Mercy’s descendants, whose names had been worn down by poverty and time but who still carried the echo of what had been stolen.

And Margaret’s manuscript, published years later under no family name at all, became a story people argued over forever.

Some called it a gothic fabrication.

Others drove past the hill where Grayson Manor still stood, empty now, windows dark, and refused to look too long at the dining room.

Because on certain nights when the snow fell silent and the birds went quiet, travelers swore they saw candlelight flickering behind those frost-blinded panes.

Not a party.

Not a feast.

Just a reminder.

That a family can inherit guilt the way it inherits bone structure.

And that the only true curse is what we refuse to name.

Mrs. Brennan lived out her days on her sister’s farm in Vermont, where she found peace in chores and sunlight and the simple fact of mornings that arrived without secrets.

Every Christmas Eve, she lit a candle and placed it in the window.

Not for the Graysons’ wealth.

Not for their tragedy.

For the choice they made when the clock demanded an answer.

Because sometimes redemption doesn’t look like survival.

Sometimes it looks like a table set for dinner, food untouched, and a family finally brave enough to stop running from the past.

THE END

News

“He removed his wife from the guest list for being ‘too simple’… He had no idea she was the secret owner of his empire.”

Julian Thorn had always loved lists. Not grocery lists, not to-do lists, not the humble kind written in pencil and…

HE BROUGHT HIS LOVER TO THE GALA… BUT HIS WIFE STOLE ALL THE ATTENTION….

Ricardo Molina adjusted his bow tie for the third time and watched his own reflection try to lie to him….

Maid begs her boss to wear a maid’s uniform and pretend to be a house maid, what she found shocked

Brenda Kline had always believed that betrayal made a sound. A scream. A slammed door. A lipstick stain that practically…

Billionaire Accidentally Forgets $1,000 on the Table – What The Poor Food Server Did Next Shocked…

The thousand dollars sat there like a test from God himself. Ten crisp hundred-dollar bills fanned across the white marble…

Baby Screamed Nonstop on a Stagecoach Until a Widow Did the Unthinkable for a Rich Cowboy

The stagecoach hit a rut deep enough to feel like the prairie had opened its fist and punched upward. Wood…

“I Never Had a Wife” – The Lonely Mountain Man Who Protected a Widow and Her Children

The knock came like a question without hope. Soft, unsure, but steady, as if the hand outside had promised itself…

End of content

No more pages to load