Autumn arrived in 1845 the way it always did in the northeastern countryside, with a polite chill that crept under doorframes and made people pull quilts higher without thinking about why. The map called the place Dutchess County, New York, but the locals didn’t speak in maps. They spoke in roads and creeks, in “past the old mill” and “before the bridge,” in landmarks that felt older than paper.

That year, the leaves turned early. A dry summer had bruised the cornfields into a tired yellow, and the wells sank lower each week as if the earth were swallowing its own thirst. Men talked about rain the way they talked about salvation. Women watched the sky like it owed them money.

And on the far side of a ridge, where a narrow road ran like a seam between farms, there sat a property people mentioned with a kind of grateful exhale.

Crowley Hollow Homestead.

If you were desperate, if you were new, if you had crossed an ocean with a prayer folded into your pocket and your last coins stitched into your hem, someone would eventually tell you the same thing.

“Go to Silas Crowley. He’ll help.”

They said it with the certainty of those who wanted the world to contain at least one reliable kindness.

Silas Crowley’s land stretched for hundreds of acres along Wappinger Creek, just enough distance from the nearest town to feel private, not enough to feel suspicious. The farmhouse was stone, squat and practical, built in the old German style that had migrated here long before Silas did. The barn was the kind that dominated a horizon, painted red as if daring the countryside to look away.

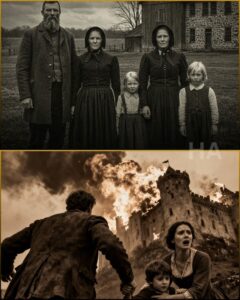

To a traveler passing by, it all looked like a portrait of American steadiness: wheat fields like combed hair, fences repaired, tools stacked neatly, smoke from the chimney as orderly as a hymn.

And Silas Crowley himself looked the part of the hymn-leader.

He was fifty-two, tall, broad-shouldered, with hands like weathered oak and a face worn into seriousness by sun and wind. He dressed like a working man who respected cleanliness: wool trousers, cotton shirt, boots scrubbed even after mud. He attended church often enough to be seen, paid his debts promptly enough to be trusted, and spoke just enough German and a smattering of Irish Gaelic to make immigrants feel less alone.

People said, “He understands,” and meant it.

For a long time, it had been true in small, ordinary ways. In the early 1830s, Silas had helped a few German families find land, offered temporary shelter, loaned tools and seed. It was charity braided with practicality. Families that survived became neighbors who bought grain and livestock. Kindness, like good fencing, could also be good business.

But by 1834 the winter came in with teeth, and the homestead suffered. Cattle died. Crops failed. Debts built their own little fortress around Silas’s pride. And somewhere inside that fortress, something in him shifted. Not with a dramatic snap, but with a slow, almost lazy turn, the way a compass needle moves when you bring iron too close.

He began to notice what desperation looked like.

Immigrant families arrived with nothing but what they could carry. They had no connections, no paperwork worth trusting, often no English. They were invisible in a way that made the world careless with them. Most importantly, they carried what little money they had left. The sum might not have been impressive to a banker in Manhattan, but on a farm scraping survival, it looked like a ladder out of a well.

Silas told himself a story that made it easier to breathe.

They won’t make it anyway.

This country eats people.

I’m only taking what the world would take.

At first, theft. Then, when theft became dangerous, silence.

The first family that vanished from Crowley Hollow was remembered only in the way a missing stitch is remembered: not with clarity, but with the nagging sense of something not finished.

The O’Rourkes. Seven of them. Irish. They arrived in spring, asking for directions west toward a steel town where a brother supposedly had work. Silas fed them, let them sleep, and in the morning he told neighbors they’d left before dawn, eager to make miles.

When the brother’s letter arrived months later, asking after them, it wandered through hands and offices like a lost dog.

“No one knows,” was the conclusion.

The road was dangerous. Families changed plans. People vanished in America all the time, if you were poor enough.

And once the world accepted that first disappearance, the rest came easier. Like a door that sticks until you learn the trick of it.

Immigrant families would arrive at night, tired and grateful. Silas would offer soup and bread and a place to sleep. They’d speak of Bavaria or Cork, of famine or soldiers, of the ocean that had tried to swallow them. In gratitude they’d share plans, destinations, and the careful secrets of their savings.

Then, sometime before morning, they would be gone.

Silas always had an answer ready, delivered with the calm honesty of a man who served on committees and prayed in public.

“They left early.”

“They got word of work elsewhere.”

“They found relatives.”

And because he was Silas Crowley, because he gave money to churches and attended meetings of the local Immigrant Aid Society, people believed him.

The organizations meant to protect newcomers became his most efficient invitation list.

He shook hands with pastors. He volunteered. He donated. He listened closely, asking careful questions with concern painted over greed.

“Family from Hamburg, you say? How many children?”

“An Irish widow? Alone? Any savings?”

“How soon do they arrive?”

He became the friendly gatekeeper at the edge of a new life, and families walked through his smile the way birds fly into glass.

Years passed. The disappearances became a shadow that moved with the sun. By 1845, some people had begun to feel that shadow at the edges of their sight, not as a clear shape, but as a collection of odd moments that didn’t quite fit together.

It started with a shopkeeper.

Martha Klein ran a general store in a small village five miles from Crowley Hollow. She had the kind of memory that made gossip unnecessary because she remembered everything anyway. Farmers were creatures of habit, she’d learned, and their purchases followed patterns as dependable as the seasons.

Silas Crowley’s pattern changed.

He began buying children’s clothing, women’s shoes, ribbons, combs, mirrors, small personal luxuries that didn’t belong to a bachelor farmer. When Martha raised an eyebrow, Silas smiled like a man who expected to be admired for decency.

“Donations,” he said. “The families come with nothing. You know how it is.”

It sounded reasonable. It matched his reputation. Still, the quantities were… generous. Month after month, enough to outfit entire households.

Then came the chemicals. Lime, and more lime. Laudanum, purchased with casual familiarity. Martha watched his hands as he counted coins, steady as a metronome.

“Animals sick?” she asked.

“Improving the soil,” he replied, and his eyes didn’t blink like most people’s did when they lied.

A traveling physician noticed something too, in a different way.

Dr. Elias Hart was called out to Crowley Hollow several times over the years, supposedly to treat ill immigrant workers. Each time, Silas met him at the edge of the property, never inside, never close enough for the doctor to see anything but fields and sky.

He described symptoms with unsettling precision. Always requested specific remedies. Always had an explanation ready for why the patient couldn’t be seen.

“Frightened of strangers,” Silas would say. “You know how they are.”

At first, Dr. Hart believed it. Many immigrants feared American medicine. But the pattern repeated too perfectly. When Hart insisted, Silas’s politeness hardened like cooled wax.

“You’ll do more harm than good, Doctor,” he’d say, and the sentence sounded like concern, but the tone sounded like control.

A priest began keeping records.

Father Johannes Brenner served a German-speaking congregation in the county. Letters came from Europe asking after families who had promised to write, promised to send money, promised to help others make the crossing.

“I thought it was just time,” Father Brenner confessed later, voice cracking with the effort of honesty. “People settle. They become busy. But the letters kept coming, and the silence kept answering.”

When he inquired, he was told the same thing again and again.

“Crowley helped them, but they moved on.”

It was always plausible. It was never provable.

An Irish blacksmith, Thomas McBride, noticed graves.

McBride had been helped by Silas once, years ago, enough kindness to create a debt of gratitude that made suspicion feel like betrayal. He visited occasionally to discuss immigrant aid work. Each visit, he saw fresh mounds of disturbed earth.

“Lost a cow,” Silas would explain.

“A horse broke a leg.”

But McBride had grown up on a farm. You didn’t bury livestock near the yard in scattered places like that. You chose a remote corner, made it practical, made it one thing.

This was many things. Too many.

The most troubling observation came from McBride’s son, Patrick, a boy young enough to say what adults were trained to edit.

On a visit in early summer, Patrick tugged his father’s sleeve and whispered, “Da… I heard crying.”

“Animals,” McBride told himself.

But the boy shook his head hard enough to make his curls bounce.

“Not animals. People. Like… like they’re scared.”

When McBride asked Silas, the farmer laughed softly, a warm sound that made the question feel silly.

“They’re emotional. They’ve lost everything,” Silas said. “You know that.”

McBride wanted to believe him. Belief was easier on the stomach.

Even the animals seemed to notice something.

Jacob Lapp, an Amish farmer who lived along the property line, spoke little English, but his animals spoke in their own language. When the wind came from Crowley Hollow, his horses grew skittish, his dogs paced and whined, and his cattle refused to graze near the fence.

“They smell death,” he told his wife in Pennsylvania Dutch.

He didn’t know what to do with that sentence. He only knew it kept returning.

And then there was the mail.

Postmaster William Harlan had delivered letters for fifteen years and liked to think of himself as a man who understood the small mathematics of human life: how much news came in, how much went out, how often a name disappeared from envelopes.

He began to notice a strange current flowing toward Crowley Hollow. Letters arrived from Germany and Ireland addressed to families “staying temporarily” at Silas Crowley’s farm.

But hardly any letters ever left.

One day, while handing Silas a stack thick enough to bend, Harlan tried to keep his voice casual.

“Busy house you’ve got,” he said. “Not much writing back, though.”

Silas smiled and tapped the letters as if they were a nuisance.

“They’re not all literate,” he said. “And I’m not a man who can spend hours with pen and ink when there’s work to do.”

It sounded plausible. It sounded generous.

It didn’t sound true.

By late summer of 1845, the county held these anomalies like stones in a pocket. Individually, they were explainable. Together, they began to weigh.

But the thing about a respected man’s reputation is that it acts like fog. It softens the edges of doubt. It makes hard shapes look harmless.

The fog might have lasted longer.

It might have lasted forever.

Except the drought grew worse, and thirst has a way of dragging truth out of hiding.

On August 23rd, a German immigrant named Johann Weber arrived in the county with his pregnant wife, Elsa, and two small children. They had landed in New York City three weeks earlier and were traveling west toward Ohio, where Johann’s brother had written of land and work.

Johann was different from many who had come before him.

He could read and write, and he kept a journal as if words could anchor a family against the chaos of a new world. He had also served briefly in the Prussian army and carried the soldier’s habit of observing details that others dismissed.

And he was cautious in the particular way only hardship teaches.

When someone in a roadside tavern suggested Crowley Hollow as a safe place to rest, Johann nodded politely and felt his stomach tighten.

By dusk, they arrived. Silas Crowley greeted them in German with the fluency of practiced charm.

“Welcome,” he said warmly. “You must be exhausted. Come, come. Food first.”

Inside the farmhouse, the air was thick with the smell of stew and woodsmoke. Elsa relaxed a little, hand resting over her belly as if it were a second heart. The children stared at Silas’s clean boots with the awe children reserve for authority.

Johann forced himself to smile.

“Thank you,” he said. “We don’t wish to trouble you.”

“Nonsense,” Silas replied. “America is built on helping each other.”

The sentence sounded rehearsed, but Johann had no proof it was anything but kind.

Then he noticed the smell beneath the stew and smoke. Not strong. Not obvious. But familiar in a way he did not want it to be.

A faint sweetness. Dry. Wrong.

He’d smelled it once after a skirmish when bodies lay too long in summer air.

He kept eating as if he hadn’t noticed. He watched the room.

On a peg near the kitchen door hung children’s clothing in European styles, too fine to be farm rags. On a small table, half hidden under a cloth, glinted a woman’s brooch. In a corner, a carved wooden cross, the kind a family might carry across an ocean like a promise.

Johann’s spoon paused.

Silas noticed everything, Johann realized. Even a pause.

“Something wrong?” Silas asked lightly.

“Long travel,” Johann said. “The body takes time to believe it is safe.”

Silas chuckled. “Yes. Safe here.”

When Silas offered to let them sleep in the barn, Johann heard himself refuse before he had time to consider politeness.

“My wife,” he said, gesturing to Elsa’s stomach, “she needs a bed indoors.”

For a moment, Silas’s smile faltered. Just a hairline crack. Then it returned, stronger, as if patched quickly.

“Of course. Family comes first,” Silas said. “I will make room.”

That night, Johann did not sleep.

He lay beside Elsa in a small upstairs room, listening to the house settle. A floorboard creaked. A door sighed. Somewhere below, a murmur that sounded too much like speech to be mice.

Elsa shifted, half waking.

“Johann?” she whispered.

“Go back to sleep,” he murmured. “Just… rest.”

But he kept listening. Around midnight, he heard muffled voices, not inside the room, not outside the window. From below, deep in the belly of the house.

German. Then something that sounded like Irish Gaelic. Pleading. Crying.

Then silence.

Johann’s fingers tightened around his journal until the leather creaked.

He thought of his children sleeping on the floor beside the bed, their faces soft in the dark. He thought of Elsa’s heartbeat and the heartbeat inside her.

He thought: This is not a place you survive by being polite.

He touched Elsa’s shoulder gently.

“Elsa,” he whispered. “We are leaving. Now.”

Her eyes opened, frightened but trusting. She did not ask why. She had married a cautious man and learned that caution saved lives.

Within minutes, they gathered their things with the quiet efficiency of people who had learned to pack fast. Johann lifted his son, carried him like a bundle of breath. Elsa took their daughter’s hand.

They slipped downstairs. The house felt like it was holding its own breath. Johann expected Silas to appear in the doorway, smiling, as if he’d been waiting.

But the hallway stayed empty.

They stepped outside. The night air tasted like dry leaves and distance. Johann guided them down the road until the farmhouse became a darker blot against the hills.

Only then did he stop in a grove of trees and kneel to meet Elsa’s eyes.

“You will stay here,” he told her. “With the children. Do not move.”

Her lips trembled. “Johann, no.”

“I must see,” he said, and hated himself for the sentence. “If I’m wrong, I will be ashamed. If I’m right… we need proof.”

He returned alone, moving like a shadow taught by fear.

From the trees, he watched the barn, its red walls dull under starlight. He watched the farmhouse.

At first, nothing.

Then the door opened. Silas Crowley stepped out, carrying a bundle wrapped in canvas. He looked around carefully, not like a man checking the weather, but like a man checking for witnesses.

He crossed to the barn and disappeared inside.

Minutes later, he emerged empty-handed.

He repeated the journey again and again, bundles moving from house to barn with the rhythm of routine.

Johann felt cold spread through his ribs.

Near mid-morning, Silas hitched a horse to a cart and rolled it out from behind the barn. Johann’s vision narrowed. The cart held shapes wrapped in canvas, arranged with a care that felt obscene.

Bodies.

Adults and children, stacked as if they were lumber.

Silas drove toward a distant part of the property where earth looked freshly disturbed. He began digging.

Johann watched until his stomach threatened mutiny. Then he ran back to his family, hands shaking, and ushered them toward town with a speed that turned walking into flight.

By the time they reached the sheriff’s office in the county seat, Johann’s German accent was thick with terror, but his eyes were steady with something stronger than terror.

Determination.

Sheriff Elias Crawford had served the county long enough to recognize exaggeration, drunkenness, and the common habit of turning rumor into drama.

Johann Weber did not smell like drama.

He smelled like a man who had seen something that rearranged his bones.

Crawford listened. Asked questions. Watched Johann’s hands, the way they held the journal like it was a weapon.

“Names,” Crawford said. “Dates. Everything.”

Johann opened the journal and began.

Ink and facts. Places. Descriptions. The smell. The bundles. The cart. The graves.

Crawford’s face grew heavier with each detail. At the end, he sat back and rubbed his forehead.

“Silas Crowley,” he said quietly, as if saying the name too loudly might summon it.

Johann swallowed. “He is not what you think.”

Crawford stared at the wall for a long moment, then stood.

“I pray you’re wrong,” he said.

And then, after another pause, he added, “But I don’t think you are.”

The sheriff did what careful men do when they’re afraid of being wrong: he gathered more proof.

He reviewed old inquiries about missing immigrants. He found too many that ended with the same vague last known location: near Crowley Hollow.

He visited Martha Klein, who produced records of purchases that made sense only if a hidden population was being fed, clothed, drugged, and erased.

He spoke to Dr. Hart, who admitted, voice tight, that he had never seen the patients he was asked to medicate.

Father Brenner brought his list of letters and names, a paper graveyard.

Postmaster Harlan brought records of mail delivered, and the terrible absence of replies.

And Thomas McBride, the blacksmith, stood in Crawford’s office with shame pooling in his eyes.

“My boy heard crying,” he said. “I told him he was imagining.”

Crawford looked at each man and woman in turn and said something that sounded like a verdict on them all.

“Sometimes evil survives because decent people don’t want to be rude.”

On September 15th, 1845, Sheriff Crawford assembled a team of deputies and volunteers. He chose men who could keep their stomachs steady and their mouths shut. He also chose, quietly, a few who had once praised Silas too loudly, because he wanted them to see what praise could blind.

They rode at dawn.

When they reached Crowley Hollow, Silas met them in the yard as if he’d been expecting a church committee.

“Sheriff,” he said warmly. “What brings you out so early?”

Crawford held up the warrant.

The warmth did not leave Silas’s face, but something inside his eyes sharpened.

“This is unnecessary,” Silas said. “I’ve done nothing but help.”

“We’ll decide that,” Crawford replied.

The search began.

They found the hidden room in the basement first, concealed behind a false wall. Inside were stacks of possessions, sorted with the tidy precision of a storehouse: jewelry, children’s toys, letters in German and Gaelic, family photographs, documents of passage, little treasures that families guarded like identity.

One deputy picked up a tiny shoe, held it like it might burn him.

Crawford’s jaw clenched. “Keep going,” he ordered, voice hoarse.

Then they forced their way into the barn despite Silas’s protests about “dangerous chemicals” and “unsafe beams.”

The barn doors groaned open.

Dust hung in shafts of light like suspended breath. The smell hit them, dry and old, and underneath it the faint sting of lime.

And there, arranged in a grotesque stillness that felt like a staged sermon, were the remains of twenty-two families seated at long wooden tables as if caught mid-meal.

Not bones scattered. Not a chaotic scene of struggle.

A tableau.

Adults slumped forward, children curled against shoulders, small hands still near cups and bowls. The air in the barn was so dry, so chemically treated, that the bodies had not fully decayed. They had become something else: preserved enough to make the horror feel present, as if the dead were only pretending not to notice the living.

One volunteer staggered back and retched.

Another began sobbing, words spilling out like prayer. “Dear God… dear God…”

Sheriff Crawford stood frozen until Johann Weber, who had insisted on coming, placed a hand on his arm.

“I told you,” Johann whispered, voice breaking. “I told you.”

Crawford forced himself to move. He stepped carefully, eyes scanning the barn with the grim focus of a man choosing sanity on purpose.

Under the floor, they found the pipes and vents, a system built to channel gas into the dining area. There were seals on the doors. There were mechanisms designed with the patience of obsession.

Silas Crowley had built a murder machine inside a building everyone drove past.

When Crawford turned, Silas was standing at the threshold, hands folded as if he were waiting to be thanked.

“I gave them peace,” Silas said, voice steady. “They would have suffered more out there.”

Crawford’s voice came out like scraped stone. “You stole their lives.”

Silas tilted his head. “I used what the world offered.”

That was the moment, later, that Crawford would remember as the true chill of the case.

Not the barn. Not the bodies.

The sentence spoken with calm conviction, as if morality were a tool and not a boundary.

Silas was arrested without a struggle. In the wagon, he looked out over his fields as if he were leaving behind a successful harvest.

The investigation unfolded like a nightmare forced into paperwork.

They excavated graves across the property, scattered so widely that it became clear Silas had treated concealment as an art. They uncovered ledgers in another hidden compartment, records of names, ages, places of origin, money taken, belongings cataloged. The words read like inventory.

The county brought in specialists from the city to help process what they found. Some men quit. Some drank. Some stared at their hands as if they couldn’t remember what hands were for anymore.

At the trial that winter, the courthouse filled every day with townspeople and strangers hungry for horror at a safe distance. The prosecutor laid the evidence out in careful steps, as if guiding the jury across a bridge over a pit.

Johann Weber testified, voice shaking only once, when he described the cart.

Father Brenner testified with tears on his cheeks, saying, “I sent them there.”

Martha Klein testified with fury, slamming her purchase book down like a gavel. “He used my store to stock his cruelty.”

Dr. Hart testified with the hollow tone of a man who would never trust his own judgment again.

And Silas Crowley sat through it all with the stillness of a man watching a play he’d already seen.

When asked why, he spoke in that same practical voice.

“They were vulnerable,” he said. “No one would notice.”

The jury returned its verdict quickly.

Guilty.

The sentence was death.

But even in the county’s relief, there was no true comfort, because the missing did not become unmissing. The dead did not step out of the barn and go home. Justice felt like locking a door after the house had burned down.

On the morning of Silas’s execution in the spring of 1846, the crowd gathered as if witnessing it might stitch the world back together. Sheriff Crawford stood apart from them, jaw tight, eyes fixed on the gallows.

Johann Weber stood beside him, Elsa holding their children’s hands.

“You saved more than your own family,” Crawford murmured.

Johann didn’t look away. “I only listened to fear,” he said softly. “Sometimes fear is wisdom wearing ugly clothes.”

After it was done, the county did what communities do when they’ve stared at a monster and realized it wore their neighbor’s face.

They tried to build meaning out of ruin.

Father Brenner organized a fund for immigrant families, this time with oversight and written records and rules. The post office began tracking mail patterns for newcomers, not as suspicion, but as protection. The Immigrant Aid Society stopped relying on single “good men” and began creating networks of accountability.

Sheriff Crawford pushed for laws that required inspections of private “boarding arrangements” for vulnerable families. He became known as difficult. He accepted the name like penance.

And the barn at Crowley Hollow, the one that had pretended to be a place of food and fellowship, was sealed. Not to hide it, but to prevent it from becoming a spectacle. In the years that followed, people argued about what should be done with it. Burn it, some said. Tear it down. Let the earth forget.

But Johann Weber returned once, years later, when his children were older and his wife’s hair had begun to silver at the temples. He stood at the fence line, staring at the red boards weathering into dullness.

His son, now tall, asked, “Why keep it?”

Johann’s eyes stayed on the barn. “Because forgetting is an invitation,” he said. “And because those families crossed an ocean believing kindness was real. They deserve to be remembered as believers, not as victims.”

In the end, the county placed a modest stone marker near the road, not dramatic, not ornate. Just names when they could find them, and words when they could not.

HERE REST THOSE WHO CAME SEEKING A HOME.

It wasn’t enough. It would never be enough.

But it was a beginning, which is sometimes the only mercy history allows.

And if the story of Crowley Hollow lingered like fog in the minds of those who lived nearby, it did so for a reason: a warning written in the quiet language of ordinary places.

Evil does not always arrive with horns and heat.

Sometimes it arrives with stew on the stove, a clean pair of boots, and a reputation for charity.

Sometimes it smiles, opens a door, and says, “You’re safe here.”

And the only thing that breaks its spell is someone, trembling and stubborn, deciding to look closer.

THE END

News

Billionaire Invited the Black Maid As a Joke, But She Showed Up and Shocked Everyone

The Hawthorne Estate sat above Beverly Hills like it had been built to stare down the city, all glass and…

Wife Fakes Her Own Death To Catch Cheating Husband:The Real Shock Comes When She Returns As His Boss

Chicago could make anything feel normal if you let it. It could make a skyline look like a promise, make…

Black Pregnant Maid Rejects $10,000 from Billionaire Mother ~ Showed up in a Ferrari with Triplets

The Hartwell house in Greenwich, Connecticut did not feel like a home. It felt like a museum that had learned…

Single dad was having tea alone—until triplet girls whispered: “Pretend you’re our father”

Ethan Sullivan didn’t mean to look like a man who’d been left behind. But grief had a way of dressing…

“You Got Fat!” Her Ex Mocked Her, Unaware She Was Pregnant With the Mafia Boss’s Son

The latte in Amanda Wells’s hands had been dead for at least an hour, but she kept her fingers curled…

disabled millionaire was humiliated on a blind date… and the waitress made a gesture that changed

Rain didn’t fall in Boston so much as it insisted, tapping its knuckles against glass and stone like a creditor…

End of content

No more pages to load