The Ironwood Fire

On the night of September 3rd, 1860, the air over Ironwood Plantation felt thick enough to chew. Summer had refused to leave Middle Tennessee. Heat still clung to the fields long after sunset, holding the smell of cotton leaf and sweat and livestock in the dark like a hand over a mouth.

If you had stood at the edge of the workyard that night, you would have heard music first. A fiddle, bright and quick, threading through men’s laughter. You would have heard boots stamping, someone shouting for another pour, and the low, satisfied talk that only comes after a harvest so profitable it makes cruelty feel, to the cruel, like a kind of blessing.

Fifteen overseers had gathered behind the gin house to celebrate the biggest cotton yield in Ironwood’s history. They had a hog on a spit. They had bourbon in barrels. They had the careless swagger of men who believed the world was arranged for their comfort, and that everyone else was simply part of the arrangement.

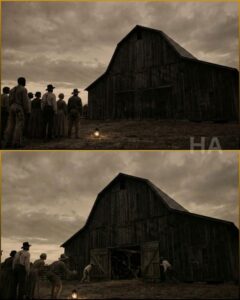

By dawn, the barn behind their celebration ground would be a black rib cage against the gray sky, its beams scorched and its doors warped. In the ash, there would be shapes that looked too human to be called debris, and a smell that wouldn’t leave the place for weeks no matter how hard people pretended it could.

And yet, if you asked anyone in authority what happened, they would call it a tragedy. A terrible accident. A consequence of drinking and lanterns and chance.

But the story of Ironwood does not begin with fire.

It begins with a boy who wanted to read.

1

Rufus Hammond was forty-one in the spring of 1860, and by then the forge had made its own map on him.

His hands were scarred, not the clean scars of a single injury but the layered proof of a lifetime: quick burns from stray sparks, deeper marks where hot metal kissed skin when the bellows surged, and calluses thick enough to make his palms look like they’d been carved from weathered leather. He stood tall, broad through the shoulders, the kind of man who did not move with wasted motion because every wasted motion costs strength you’ll need later.

The white men on Ironwood tolerated Rufus for one reason: he was valuable.

A plantation that size ran on metal the way a body runs on blood. Horseshoes. Hinges. Plow blades. Chain links. Nails. Tools that broke, tools that dulled, tools that had to be sharpened and repaired and replaced. Rufus kept the whole machine running, which meant even men who enjoyed whipping others knew better than to ruin the hands that kept their own work possible.

He lived, like everyone enslaved at Ironwood, under a system that demanded constant submission. But the forge gave Rufus something rare: a room where his expertise mattered more than anyone’s mood. A room where he could close his fingers around a hammer and feel, for a few hours, like the world answered to him instead of the other way around.

It was the only kingdom he was allowed.

What most people did not know, and what Rufus did not advertise because knowledge was its own kind of danger, was that his skill had been inherited like a secret.

His father, Wame, had been a blacksmith long before he became property. Rufus remembered his father’s voice more than his face now: a low tone speaking an African language only whispered when no white ears were near. Wame spoke about fire the way some men speak about weather, as if it had moods and habits you could learn if you paid attention. He taught Rufus that wood mattered. That wind mattered. That heat could be coaxed or cornered. That metal could be shaped into tools, but tools had edges, and edges had purposes beyond work.

Most of all, Wame taught him a sentence Rufus carried like a stone in his pocket:

Fire does not respect rank.

Rufus had been born into slavery. He knew nothing of Africa except what his father smuggled across generations in fragments of language and memory. He grew up learning how to make himself invisible in the ways that kept boys alive: eyes down, voice quiet, obedience ready.

And still, inside him, something stayed awake.

He watched what the overseers did. He watched women double over in fields and still get struck for moving too slowly. He watched mothers panic when traders visited, because a man on a horse meant a child might vanish by dusk. He watched the way cruelty became casual, the way some men joked while doing things that should have taken their sleep away forever.

Rufus did not talk about his anger. Anger in chains is a private thing. It has nowhere safe to go.

So he stored it.

He filed it in the back of his mind the way he organized tools along the forge wall, each memory hung in its place, waiting for a day he didn’t expect to arrive.

Then Abel Hammond found a Bible.

2

Abel was sixteen and still soft around the edges in a way that terrified Rufus.

Not soft in strength. The boy worked. He had the shoulders of someone who’d spent years hauling feed and brushing down horses, his arms already thickening with use. But Abel’s eyes were open in a way Rufus wished he could close. They held curiosity like a candle holds flame, and Rufus had lived long enough to know that on a plantation, a candle left unattended can burn a whole house down.

Abel worked in the stables. It was considered a “better” position, if anything in slavery can be called better. The horses mattered to Whitfield’s pride, so the stable hands were kept close, watched hard, and fed just enough to keep them upright. Abel was good with animals. He spoke to them softly. He understood temperaments. He could calm a nervous mare with a steady palm and a hum under his breath.

The problem was that Abel wanted to understand everything else, too.

He asked questions Rufus tried not to answer. Why did thunder sound like that? Why did some plants heal and others poison? Why did white children in the big house get to sit with books while enslaved children were told that learning was “not for them”?

Rufus warned him, gently at first, then harder.

“Curiosity gets you hurt,” he said one night, voice low in their cabin. “You want to live, you don’t go reaching for what they say ain’t yours.”

Abel nodded like he agreed. Then he kept reaching anyway, just more carefully.

In the winter of 1859, one of the overseers left a Bible on a bench in the stable. It was the kind of careless act white men could afford. A thing set down and forgotten, because the person who might want it was not considered fully human.

Abel picked it up like it might bite him.

He hid it in the loft, under hay. He opened it in stolen minutes when the stable was quiet. He stared at the symbols until his eyes watered. At first they meant nothing, just marks. But he’d heard scripture spoken at church. He’d heard hymns. He’d listened to the preacher talk about obedience and reward and suffering as if suffering were holy when it belonged to someone else.

Abel began matching sounds to shapes.

It was slow, stubborn work. The kind of work that makes you feel, for the first time, that your mind is your own.

Rufus found out when Abel, half asleep one night, whispered a word to himself like a victory.

Rufus’s stomach dropped.

He should have taken the Bible. Burned it. Buried it. Anything.

But Abel looked up, eyes shining in the low light, and said, “Papa… I can see it. I can see what they been keeping.”

Rufus wanted to slap him and hug him at the same time.

Instead, he said the only thing that mattered.

“You never do it where anybody can catch you.”

Abel promised.

Promises on a plantation are fragile as glass.

In March of 1860, Overseer Silas Burke climbed the stable ladder and found Abel in the loft, the Bible open, the boy’s lips moving as he tried to sound out a line.

Burke did not shout at first. He smiled.

That smile was what Abel remembered most later, in the seconds where remembering was still possible. A smile like a dog’s bared teeth.

“Well,” Burke said, voice syrupy with malice. “Look what we got here.”

Abel tried to close the book. Tried to hide it. Tried to explain, because children still believe words can fix what fear has already decided.

Burke grabbed him by the collar and dragged him down, Abel’s feet hitting rungs, then air, then ground.

Across the yard, the big house sat white and quiet, the porch wide, the windows dark like watching eyes.

Rufus saw Abel being hauled past the forge. He saw the book under Burke’s arm. He felt his body go cold and hot at once.

He took one step forward, then stopped, because stopping is what survival teaches you.

He followed at a distance, not running, not shouting, moving like a man walking into his own funeral.

3

Cornelius Whitfield kept his study neat. He liked things orderly: account books stacked, pen laid straight, maps pinned clean to the wall. He wore expensive clothes even in heat. He spoke in an educated drawl, soft enough to sound reasonable even when he was saying something monstrous.

When Burke shoved Abel into the study and held up the Bible like evidence, Whitfield didn’t explode.

He became still.

“You know the law,” Whitfield said.

Abel’s voice trembled. “I didn’t mean no harm. I just… I just wanted to know.”

Whitfield looked at him as if Abel had confessed to stealing silver.

“What you want,” Whitfield said, calm as a man discussing weather, “is not your concern. Your concern is obedience.”

He turned his gaze toward the yard, as if imagining it already filled.

“Summon the overseers,” he said. “Bring everybody.”

The words traveled faster than feet. Enslaved people were pulled from cabins, fields, kitchens, stables. Children were dragged along, their eyes wide because even they knew what an assembly meant. The whipping post in the yard was old oak, smooth from years of bodies pressed against it. Iron rings were bolted into it at different heights, because the plantation had learned to punish people of every size.

Abel was stripped to the waist and tied up.

Rufus stood in the crowd, his hands clenched so tight his nails cut into his palms. He did not step forward. He did not beg. He did not make a sound. He had seen what happened to men who tried to stop a punishment. He knew the system enjoyed punishing the protest almost as much as the “crime.”

Whitfield spoke from the porch like a judge delivering a sermon.

“This boy has violated the laws of Tennessee,” he announced. “He has attempted to rise above his station. The state’s penalty is severe. I choose mercy. He will receive one hundred and forty-seven lashes.”

A murmur moved through the crowd like wind through dry grass.

Rufus did not breathe.

Whitfield continued, voice smooth. “One for each year since Ironwood was founded. A reminder of order. A reminder that God placed each soul in its proper place.”

Then the overseers stepped forward, fifteen men in a line, each holding a whip as if it were simply another tool of work.

Rufus watched the first strike land.

He watched Abel’s body jerk.

He watched Abel fight for dignity and fail, because no one can stay dignified when their body is being made into a lesson.

The sound was what Rufus remembered most afterward: leather cracking, a sharp intake of breath, the hush of a crowd forced to witness its own terror.

At some point Abel stopped screaming. Not because the pain stopped, but because his voice ran out.

Salt water was thrown. Commands were barked. The ritual continued, because cruelty is always patient.

Rufus stood still, because movement would have been a death sentence, and because he believed, in the deepest part of him, that if he endured this moment without breaking, maybe Abel would live.

When the punishment finally ended, Abel sagged against the ropes like a puppet with its strings cut.

Whitfield nodded once. “Untie him. Put him in the infirmary. He’ll heal.”

As if healing were a switch you could flip.

As if a boy could be reduced to a warning and still return to work like nothing had happened.

When the ropes were cut, Abel fell.

Rufus caught him.

For a second Rufus felt Abel’s weight, warm and living. He felt his son’s breath against his shirt. He leaned close, desperate for any word.

Abel’s eyes found his.

His lips moved.

Rufus did not hear the sound, but he saw the shape of it.

A word Abel had been practicing. A word Abel wanted to claim before the world took everything else.

Then Abel went still.

Rufus held him in the yard, with the whole plantation watching, and something inside Rufus did not shatter like glass.

It split like wood under pressure, clean and irreversible.

He lifted his head and looked at the overseers.

He did not glare the way a man in anger might. He did not spit. He did not threaten, because threats require power.

He simply saw them.

He saw Burke’s grin. He saw the others’ casual relief, the way they shifted like men who believed their day’s work was done. He watched Whitfield turn and walk back into his house as if he’d just signed a check.

And Rufus stored every face the way he stored firewood, stacked neat for the winter.

That night Rufus buried Abel in the woods behind the quarters, where unmarked graves made the ground uneven with history.

No service was allowed. No prayers spoken aloud.

So Rufus prayed in silence, because silence was the only thing the plantation couldn’t whip out of him.

And in that silence, a plan began to form. Not in rage. Rage burns fast. This was something colder, something built from the same discipline that shaped iron into blades.

Rufus returned to the forge the next morning and worked.

He repaired tools for men who had killed his child.

He fixed hinges on doors that locked other people in.

He did it with a face so neutral it fooled Whitfield into writing, later, that “order has been restored.”

Order, Rufus thought, is just cruelty wearing clean clothes.

4

Time on a plantation has a strange way of moving. Days are long when you are exhausted. Months disappear when nothing changes.

Spring turned into summer. Cotton grew high. The Tennessee heat settled in like a punishment of its own. The overseers acted more emboldened, not less, as if Abel’s death proved the system could do anything it wanted and still sleep at night.

Rufus watched them.

He watched their routines. He watched where they gathered when they drank. He watched which doors they closed and which they left open. He listened to their jokes, because jokes reveal what men think is normal.

Saturday nights were always the worst. The work done, the profits counted, the overseers treated the plantation like a tavern and the enslaved people like furniture.

After Ironwood’s record harvest, Whitfield announced a celebration for the overseers. A bonus. A barrel of bourbon. A night of music.

For Whitfield, it was a reward system: keep the men who enforced his “order” happy so they stayed loyal.

For the overseers, it was an excuse to become careless.

And for Rufus, it became a date on an invisible calendar.

He did not speak it aloud. He did not share it with anyone, not because he didn’t trust the enslaved people around him, but because he understood fear. He understood what a human mouth can do under threat.

So he carried the plan alone.

He moved like a man doing nothing.

He requested supplies for the forge that made sense. He ran errands that gave him access to places other enslaved people were not allowed. He used his value like a key, turning it quietly in locks that no one realized were being tested.

He watched the weather. He watched the wind.

And all summer, he kept seeing Abel’s mouth forming that last word, a word Rufus could not stop hearing in his head.

A word that felt like both a blessing and a theft.

In late August, Whitfield’s happiness sharpened into arrogance. He talked in church about prosperity. He bragged at the market about his yield. He laughed with other planters who congratulated him as if the cotton had grown itself.

He didn’t see the way the enslaved people moved differently now. Quieter. More watchful. Not hopeful, exactly. Hope was dangerous. But something had shifted. Abel’s death had not crushed everyone the way Whitfield wanted.

It had taught them that the system’s cruelty had no bottom.

And when cruelty has no bottom, people stop expecting it to be fair.

They start expecting it to end.

5

September 3rd arrived clear and brutal. The heat returned hard, the sky pale and cloudless as if it couldn’t be bothered to offer shade. The day’s work dragged. Tempers were short. Sweat stung eyes. The overseers barked orders and took out their discomfort on any enslaved person who moved too slowly.

Rufus worked at the forge, hammering in a steady rhythm that masked the shape of his thoughts.

When dusk came, the plantation changed its face.

The overseers began their celebration behind the gin house. Meat roasted. Bourbon poured. A fiddle player from town scratched out dance tunes that sounded cheerful until you remembered who was dancing.

Whitfield, not interested in what he considered low company, retreated into the big house and told them, with a thin smile, not to burn anything important.

It was said like a joke.

The night deepened. Laughter carried. The overseers moved their party toward the cotton barn, a huge wooden structure where bales were stored before shipping. The barn was cooler inside, the thick walls holding back some of the heat. They dragged chairs in. They played cards on a barrel lid. They drank until the world softened around the edges.

And then they shut the big sliding doors partway, to keep insects out, to keep the music contained, to keep themselves comfortable.

They locked themselves into the very place that held the plantation’s wealth, surrounded by cotton that had been picked by hands that bled.

Rufus did not go near the party. He did not look like a man with purpose. He walked, as he always did on Saturday nights, toward the quarters where people gathered to sing. Spirituals floated into the night, quiet but stubborn. Old Esther led the song, her voice worn and steady, as if it had survived every kind of storm.

Rufus sat near the edge of the group, his back against a cabin wall. He listened to the voices around him. He watched faces in the dim light: mothers, fathers, children, people who had learned to live with grief as a roommate.

He waited.

He did not smile. He did not tremble. His calm wasn’t peace. It was focus.

At some point, far across the yard, a sound changed. A sudden shout. A scramble. Then a deep, wrong roar, the kind of sound that makes human beings instinctively look up because the body knows what fire means even before the mind catches up.

The sky beyond the trees pulsed orange.

People stood.

Someone whispered, “Lord.”

The overseers’ laughter turned to chaos.

The cotton barn, once a shadow against the night, began to glow from within like a lantern turned monstrous. Flames pushed through gaps in wood. Smoke rolled out, thick and black, crawling low before it rose. Wind carried sparks like angry insects into the dark.

From the quarters, the enslaved people watched, frozen between fear and something that felt too complicated to name.

Whitfield’s house lit up with movement. A door slammed. Horses whinnied. A man’s voice shouted orders.

And then, from the direction of the barn, came a sound Rufus had not expected to hear so clearly: men pounding on wood, shouting, voices cracking with terror as they realized comfort had become confinement.

Someone screamed for a key.

Someone screamed for water.

Someone screamed as if screaming could turn back time.

Rufus did not move.

His hands rested on his knees, palms up, as if he were waiting for rain.

Old Esther kept singing, voice shaking but stubborn, because what else could she do? The song wavered and then steadied again, a thin rope thrown across a dark river.

Rufus stared at the orange light and thought of Abel in the yard, Abel’s eyes finding his, Abel’s mouth shaping that last stolen word.

And in that moment Rufus understood something that did not feel like victory, only inevitability: the plantation had taught him every day that human life could be treated like fuel, so tonight fuel had finally found its flame.

“In a world that forbids a boy’s letters,” Rufus thought, “fire becomes the only language they can’t pretend not to understand.”

He bowed his head, not in celebration, but in mourning for what had been done, for what had been taken, and for what would now never be undone.

The barn burned until it could not hold itself upright.

Men who had never begged in their lives begged.

The night carried their voices for miles.

On Ironwood, enslaved people were ordered to form bucket lines, to “help,” to perform obedience even as the heat made it obvious nothing could be saved. Rufus stood when told. He carried water when commanded. He moved with the same steady pace he always used, because anything else would have made him stand out.

But inside him, something remained still.

Not empty. Not relieved.

Just still, the way a hammer rests after it has struck.

6

By morning the barn was a charred shell. Cotton, wealth, and certainty were gone, replaced by ash that drifted over the fields like dirty snow.

Whitfield stood near the ruins, his face pale, his eyes too bright. He spoke loudly about accidents, about whiskey, about lanterns and carelessness. He needed the story to be simple because simple stories keep systems alive.

But the pattern of destruction did not feel simple to anyone who lived under his rules.

Fifteen overseers were dead.

The men who had carried whips and pistols like extensions of their hands were now gone from the world, removed in a single night. Some people whispered about judgment. Some whispered about rebellion. Some whispered about a curse.

No one said Rufus’s name aloud.

Not because no one suspected. Because suspicion was a kind of respect, and respect was dangerous.

Whitfield questioned people for days. He threatened. He promised rewards. He demanded answers.

Enslaved people looked at him with blank faces and said nothing useful, because silence can be a form of resistance when words are too expensive.

Whitfield hired new overseers, but the new men arrived nervous. They looked at every barn like it might swallow them. They kept pistols close. They slept lightly. They treated their whips less like toys and more like protection.

Fear changed the plantation’s rhythm.

Work slowed. Accidents increased. Tools broke. Horses went lame. The cotton gin jammed.

Whitfield saw sabotage in every inconvenience, but he could not prove it. He had built a world on control, and now control felt flimsy.

In November, Abraham Lincoln was elected president, and the South began to rumble with talk of secession. Ironwood existed in a tension that had nothing to do with weather now. Planters met in town and spoke with anger and panic. Poor whites argued in taverns. Everyone sensed the ground shifting.

Whitfield tried to hold his plantation steady with tighter rules, harsher punishments, more surveillance.

But fear does not create loyalty. It creates cracks.

Rufus continued to work at the forge.

He woke before dawn. He lit the fire. He shaped metal into whatever Whitfield demanded. He spoke only when necessary. His face remained unreadable.

Inside him, Abel remained alive in the only way he could: in memory.

On December 3rd, 1860, Whitfield was found dead in his study.

The doctor said heart failure. Stress. A man worn down by loss and worry.

Enslaved people whispered different explanations, because when you live under oppression you learn that truth is sometimes safer dressed in superstition. They said Whitfield had been visited by the dead at night. They said he saw faces in the smoke. They said the barn fire had entered his lungs and never left.

Whatever the cause, the result was the same.

Ironwood’s power fractured.

Whitfield’s widow, overwhelmed and terrified of the land itself, sold the plantation within months.

People were sold with it.

Rufus was sold south in the summer of 1861, chained and transported like a tool changing hands. The forge he had ruled was left behind. Abel’s grave in the woods was left behind.

Rufus did not cry on the road. He had cried all his tears the day Abel died. What he carried now was heavier than water.

He carried a story.

7

The Civil War came like a storm that had been building for years. Enslaved people listened for news the way thirsty people listen for rain. Names traveled mouth to mouth: battles, presidents, proclamations, rumors of freedom.

Rufus ended up on a plantation in Alabama, his skills used again, his value protecting him again in the narrow way value can protect a person who is still property.

He worked through the war years. He watched men in gray march past, then not march back. He watched hunger and fear gnaw at white households that had once acted invincible. He watched the system wobble under the weight of its own violence.

In 1865, when the war ended and slavery was legally abolished, freedom did not arrive like a clean sunrise. It came uneven, messy, delayed by politics and threats and old habits that refused to die.

But it came.

Rufus, older now, with more gray in his hair and more smoke in his lungs, walked away from the Alabama plantation with nothing but his hands and his name.

For a while he drifted. He took work where he could: shoeing horses, repairing tools, doing what he knew. He slept in corners and under roofs offered by people who had once been enslaved and now tried, with trembling hands, to build lives that belonged to them.

He did not speak much about Ironwood. Not because he forgot. Because memory can be dangerous even after chains are cut. The South was still full of men who missed the old world and wanted to punish anyone who looked like proof it had ended.

But Rufus spoke about Abel.

He spoke about Abel quietly, to people he trusted, in the tones fathers use when they are telling their children’s names so the names do not vanish.

And when Reconstruction brought, briefly, the possibility of schools for Black children, Rufus did something that would have made Whitfield choke on his own certainty if he had lived to see it.

Rufus helped build one.

Not with speeches. Not with politics. With hammer and nail, with hinges forged straight, with ironwork that held a door in place so children could walk through it.

He stood outside the schoolhouse the first day it opened and listened to the sound of children inside trying to shape letters with their mouths.

It was not a pretty sound. It was awkward, messy, hopeful.

It was Abel’s hunger, multiplied.

Rufus did not go inside at first. He stood in the doorway and watched, hands at his sides, shoulders squared like a man bracing against a blow.

A teacher, a young woman with steady eyes, looked at him and said, gentle, “You got kids?”

Rufus’s throat tightened. He managed, “Had a boy.”

“What was his name?”

Rufus swallowed. “Abel.”

The teacher nodded as if she understood the weight of that. “Then we’ll read for him too.”

Rufus stepped inside.

Years later, when Rufus was an old man with grandchildren climbing into his lap, he told them the story the way his father had told him stories: in fragments at first, then fuller, then with the kind of honesty age allows.

He told them about Wame and the forge. He told them about Ironwood. He told them about Abel and a Bible and laws that feared a child’s mind.

He did not describe the barn fire with pride. He did not ask for forgiveness either. He spoke of it like a scar: proof of injury, proof of survival, proof that healing never erases what happened.

His grandchildren listened, eyes wide, pencils in hand, because they could write now. They could hold language in their fists like a tool.

“Was it wrong?” one of them asked, voice small.

Rufus looked at the child and saw Abel’s face in the curve of the cheek, the brightness in the eyes.

He took a long breath.

“I don’t know,” he said honestly. “I know what was done to your uncle. I know what was done to all of us. I know the law didn’t protect us. I know I loved my boy more than I loved my own safety.”

He pressed his rough thumb against the child’s knuckles, a gentle weight.

“And I know this,” he added. “You learn to read. You learn to write. You make a world where nobody can take your words away. That’s how we don’t end up back in the dark.”

Outside, the South kept arguing with its own history. People built monuments to men who fought to keep slavery alive. People told stories that made the past sound cleaner than it was. People insisted cruelty had been normal, as if normal could ever mean right.

But in Rufus’s house, in the candlelight, children read aloud.

They read scripture without fear of lashes. They read newspapers. They read books that carried whole worlds inside them.

Rufus listened, eyes closed, the sound of their voices steady as a hammer’s rhythm.

In the end, the fire at Ironwood became legend in whispers, the way forbidden truths often do. Some called it justice. Some called it murder. Most called it a warning.

Rufus never named it.

He simply remembered Abel.

And he made sure Abel’s last word was not lost to ash.

THE END

News

He arrived at the trial with his lover… but was stunned when the judge said: “It all belongs to her”.…

The silence in Courtroom 4B was so complete that the fluorescent lights sounded alive, a thin electric buzzing that made…

He ruthlessly kicked her out pregnant, but she returned five years later with something that changed everything.

The first lie Elena Vega ever heard in the Salcedo penthouse sounded like a compliment. “You’re so… lucky,” Carmen Salcedo…

“Papa… my back hurts so much I can’t sleep. Mommy said I’m not allowed to tell you.” — I Had Just Come Home From a Business Trip When My Daughter’s Whisper Exposed the Secret Her Mother Tried to Hide

Aaron Cole had practiced the homecoming in his head the way tired parents practice everything: quickly, with hope, and with…

“He removed his wife from the guest list for being ‘too simple’… He had no idea she was the secret owner of his empire.”

Julian Thorn had always loved lists. Not grocery lists, not to-do lists, not the humble kind written in pencil and…

HE BROUGHT HIS LOVER TO THE GALA… BUT HIS WIFE STOLE ALL THE ATTENTION….

Ricardo Molina adjusted his bow tie for the third time and watched his own reflection try to lie to him….

Maid begs her boss to wear a maid’s uniform and pretend to be a house maid, what she found shocked

Brenda Kline had always believed that betrayal made a sound. A scream. A slammed door. A lipstick stain that practically…

End of content

No more pages to load