The Story

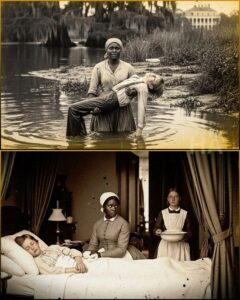

No one at Riverside Plantation could have imagined that the day young Master Thomas nearly drowned would become the first loose thread in a tapestry of lies, stitched so tightly it had passed for “respectability” in Charleston drawing rooms.

I want to be transparent before we begin: Esther is a fictional name, and so is Riverside, and the Whitmores as I’ll describe them. But the shape of this story, the machinery behind it, is not a fantasy. The patterns are carved into plantation ledgers, court records, private letters, and the testimonies of people who survived bondage and still found the strength to speak.

Sometimes history doesn’t arrive as a parade. Sometimes it arrives as a splash.

April 17th, 1841

The low country morning tasted like iron and wet earth. Spring rains had fattened the Ashley River until it moved with a hurry that felt almost angry, sliding past the docks as if it had somewhere urgent to be. Mist hovered above the rice fields in soft sheets, hiding the mud scars where bare feet and wagon wheels had been grinding the land into submission for generations.

Esther had been awake since before the stars let go.

Her day began the way most days did: hauling water from the well, building kitchen fires from half-damp kindling, scrubbing last night’s pots until the metal showed through soot like bone. She moved quickly, not because she wanted to impress anyone, but because the plantation ran on a cruel arithmetic. Work was never done. Rest was always suspicious.

At thirty-two, Esther had the look of someone older, not from weakness but from years of being forced to spend her body like currency. Her hands were calloused in a way that made thread catch on her skin. Her shoulders had learned to round slightly forward, a posture that said I am not a threat, even though something in her eyes refused to flatten all the way. That spark was her private possession. She hid it like a match in a storm.

Riverside belonged to Baron Edward Whitmore, a man whose title was more social than legal, spoken with a genteel smile by men who liked pretending America wasn’t built from borrowed crowns. Whitmore owned thousands of acres of rice and almost three hundred enslaved people, as if the law itself had signed a deed to human breath.

In Charleston, he was known as a patron of “family values,” a man who donated to churches and spoke eloquently about honor. On Riverside, his honor took the shape of overseers, whips, and ledgers that listed people like livestock.

His wife, Catherine Whitmore, wore her gentility the way fine women wore pearls: polished, visible, and tight enough to restrict movement. She filled the big house with French silks and fresh flowers, and she filled her own face with the practiced calm of a woman expected to represent purity while standing atop a system that required constant violence to remain standing.

Their only legitimate child, Thomas, was twelve that spring. He was thin in the shoulders, pale in the cheeks, and prone to coughing fits that sent the household into a panic. The baron’s love for him was not subtle. It lived in the way Edward’s voice softened when he spoke the boy’s name, and in the way he spoke about inheritance as if money and land were forms of immortality.

“Everything I do,” the baron liked to say, “I do for Thomas.”

That morning, Thomas slipped his tutor the way some boys slipped chores. He wandered down toward the river dock where barrels were loaded onto skiffs, where ropes creaked and water slapped wood in a steady rhythm. The river was high from rain. The current ran fast enough to tug at the pilings.

Esther was walking toward the washing stones with a heavy basket of laundry when she heard it.

A splash. Then thrashing that didn’t sound like play.

The basket slid off her hip and thudded into the mud. Esther ran without thinking, her skirts dragging, her breath burning. She rounded the last cluster of reeds and saw a pale arm flailing, fingers grabbing at nothing.

Thomas’s head went under, popped up, went under again.

Time did something strange. It narrowed. It turned into a tunnel with only one way forward.

Esther knew the rule. Every enslaved person on Riverside knew it: don’t touch the master’s child unless ordered. Don’t lift your eyes. Don’t make yourself equal in a moment that might be remembered later.

But rules were for people who had choices.

Esther plunged into the river.

Cold seized her like teeth. The current yanked at her skirts, trying to pull her under as if the water itself resented her interference. She fought, kicking hard, arms slicing through brown waves toward the boy’s frantic splashes.

Her fingers caught cloth. She grabbed Thomas’s shirt and hauled him close, looping one arm under his chest while the other clawed them toward shore.

The river tried to keep them.

Esther tried harder.

When her knees finally hit mud, she dragged Thomas onto the bank. His face looked wrong, too still, lips tinged blue. Esther rolled him onto his side and pressed hard between his shoulder blades. Water spilled from his mouth. She pressed again. Again.

“Breathe,” she whispered, voice shaking. “Please. Child, breathe.”

She didn’t know if she was talking to Thomas or to God.

Thomas coughed. Once, then again, and air rushed back into him like a door being forced open. His eyes fluttered, wide and terrified, and for a moment he clung to Esther’s sleeve like she was the only solid thing left in a world made of water.

Then Esther heard screaming from the big house.

Mistress Catherine had seen everything from an upstairs window. Her cry wasn’t gratitude. It was pure fear dressed in velvet.

Within minutes the riverbank filled: the baron running hard enough to loosen his cravat, Catherine following with her skirts gathered, the overseer trailing like a shadow, servants spilling out behind them.

Catherine dropped to her knees beside Thomas and pulled him away from Esther as if Esther’s hands carried plague instead of life.

“My baby,” Catherine sobbed, patting his wet hair, searching his face. “Thomas, what happened?”

“A… a woman…” Thomas wheezed, pointing weakly, eyes still unfocused.

One of the field hands, trembling with boldness he’d regret later, spoke up. “He was drowning, ma’am. Esther pulled him out.”

The baron stood frozen, staring at the boy gasping in his wife’s arms, then at Esther kneeling in mud, soaked through, shaking with cold.

For a long moment, no one spoke. The river kept running as if it was bored with human drama.

Then Baron Edward Whitmore did something unexpected.

He reached down and helped Esther to her feet.

“You saved my son,” he said, voice thick, almost sincere. “What is your name?”

Esther kept her eyes lowered. “Esther, sir.”

“Esther,” he repeated, like he was tasting the word. “You will be rewarded.”

Rewarded. It was a strange thing to promise someone who wasn’t allowed to own her own time.

Esther nodded, because nodding was safer than anything else.

But as Catherine gathered Thomas and hurried him back toward the house, Esther felt something colder than river water settle in her stomach.

Saving the master’s son meant she had been seen.

And being seen at Riverside was never simple.

The Fever Room

Thomas’s fever arrived that night like a second drowning.

By dawn his skin was slick with sweat and his eyes rolled strangely, as if he was watching something invisible hover above the bed. Catherine refused breakfast, refused sleep, refused to leave his side. The baron sent a rider to Charleston for a physician, the best money could buy, because money was the Whitmores’ favorite kind of prayer.

The doctor arrived in a cloud of horse sweat and authority, carrying bottles of laudanum and bitterness. He bled Thomas with practiced hands. He frowned at the boy’s lungs. He murmured about “constitution” and “delicate humors” and left behind instructions that sounded like guesses dressed as science.

Thomas thrashed and moaned.

He called for water. Then screamed at the word water.

Esther was sent upstairs with fresh linens on the second day, her reward already taking shape in unexpected ways. In most houses, an enslaved woman wouldn’t be allowed near the master’s sickbed unless she was there to clean what was left behind.

But Catherine was desperate, and desperation has always been more powerful than pride.

Esther stepped into the sickroom and felt heat hit her face, thick as soup. The air smelled of sweat, vinegar, and fear. Curtains were drawn to dim the light. A Bible sat open on a table like a witness who refused to speak.

Thomas lay twisted in sheets, cheeks flushed, lips cracked.

Esther moved quickly, placing the linens, keeping her gaze down.

Then Thomas’s hand shot out and grabbed her wrist.

His grip was weak but frantic.

“Don’t leave,” he whispered. “The water… don’t let the water take me.”

Catherine started to pull Esther away, offended by contact, but Thomas’s grip tightened, and his breathing hitched as if Esther was the only thing holding him to the world.

Esther did something she didn’t have permission to do.

She sat.

She let Thomas keep hold of her hand, and she leaned close enough for him to hear her voice without straining.

“You safe,” she murmured, slow and soft. “You on land. You breathing. I got you.”

The boy’s chest eased. His eyes fluttered closed.

Catherine stared at Esther as if Esther had performed witchcraft.

The baron stared too, but in his expression Esther saw something else: calculation. The kind of look men like him used when weighing profit.

“If she calms him,” Catherine said, voice tight, “then she stays.”

It wasn’t a question.

And so Esther became a fixture in the sickroom, day and night, her body positioned near the heir like an amulet.

It was an impossible intimacy. She heard Catherine pray and then curse in the next breath. She watched the baron pace, fingers stained with ink from his ledgers, his love for his son mixed with something harder: panic over what would happen to his empire if Thomas didn’t survive.

And at night, when Thomas finally slept in a quieter, less haunted way, Esther found herself noticing the rest of the room.

On the third night, a young enslaved girl came in to refill lamps and carry out soiled cloths. She moved quickly, eyes down, shoulders tense. She couldn’t have been more than sixteen.

Her name, Esther learned, was Clara.

In the lamplight, Clara’s face turned slightly as she reached for the oil. Her hairline formed a sharp widow’s peak that looked painfully familiar.

Esther’s breath caught.

Because Thomas had the same hairline.

Clara lifted her head for half a second, and Esther saw her eyes.

Green.

Not hazel. Not muddy brown. Green like river glass.

The same green as Baron Whitmore’s.

Esther felt as if the sickroom had tilted. As if the floor had become water again.

She forced her face blank, the way survival demanded, but inside her mind a door creaked open.

Clara moved out of the room, silent as smoke.

Esther couldn’t stop staring at the place she’d been.

Over the next days, Thomas’s fever rose and fell like a tide. Esther stayed by the bed, soothing him through nightmares, coaxing broth past his lips, wiping sweat from his brow. In the spaces between crisis, she watched the house.

And she began to see it.

Once you notice a pattern, it starts shouting.

Jacob, a stable hand with the baron’s jawline and broad shoulders.

Ruth, a kitchen child no more than eight, who laughed with the baron’s exact rhythm, like a familiar tune played on a cheaper instrument.

Samuel, a field man in his twenties, whose gait carried the same confident swing as Edward Whitmore walking down the porch steps in polished boots.

It wasn’t one coincidence.

It was a family tree planted in poisoned soil.

Esther’s stomach turned each time she looked at them, because the truth arranged itself with awful simplicity.

The baron had fathered children with enslaved women.

And those children were enslaved on his own land.

His blood working his fields. His blood scrubbing his floors. His blood being punished, sold, separated, and priced.

What shook Esther most wasn’t that he’d done it. In the quarters, women whispered truths the big house pretended didn’t exist. Men like the baron took what they wanted. Consent was a word that couldn’t survive inside a system built on ownership.

What shook Esther was the way the plantation demanded everyone pretend it was normal.

What shook Esther was the question that followed her like a shadow:

Did Catherine know?

The mistress’s face stayed smooth, composed, even as she watched Clara move through the hallways. If Catherine saw the resemblance, she didn’t let it crack her porcelain mask.

Or maybe she had learned to live without looking directly at the truth.

That was one of slavery’s quietest weapons: it forced people to accept contradictions until their minds broke into compartments just to keep functioning.

Thomas’s fever broke on the eighth day. He woke thin and exhausted, but alive. Catherine cried with relief. The baron poured brandy into a glass with shaking hands and drank like he was trying to wash fear from his throat.

He kept his promise to Esther.

She was given a small cabin of her own on the edge of the quarters, something almost unheard of at Riverside. She was removed from fieldwork and assigned permanently to the big house.

To anyone watching, it looked like mercy.

To Esther, it felt like being moved closer to a fire.

Because now she was inside, every day, watching the Whitmore family eat from silver while their hidden family slept in rough cabins and woke before dawn to be owned.

The Ledger of Blood

Privilege on a plantation is still a cage, just with cleaner bars.

Esther’s new duties kept her near Catherine: dressing the mistress’s hair, fetching water for baths, polishing candlesticks until her arms burned. She learned the rhythms of the big house the way a sailor learns tides.

She also learned which doors stayed locked.

The baron had an office off the main hall, a room that smelled of ink, tobacco, and paper. The door was usually closed. Inside, Edward Whitmore kept his ledgers, his correspondence, and the legal language that made bondage look respectable on a page.

Esther was not supposed to enter.

But one afternoon in late summer, Catherine sent Esther to retrieve a shawl from the baron’s office, thinking he was out inspecting the fields.

Esther hesitated at the door. Her heart beat against her ribs like it wanted to warn her away.

Then she stepped inside.

The room was cooler than the rest of the house, shutters angled to keep sunlight from fading documents. On the desk sat an open ledger, its pages filled with tight handwriting.

Esther didn’t intend to read it.

But her eyes snagged on a list of names.

Clara.

Jacob.

Ruth.

Samuel.

Beside each name, a number.

Not ages.

Prices.

Below, a note in the baron’s hand: Do not sell until the Charleston matter is resolved.

Esther’s fingers went cold. She turned a page, breath shallow. Another list, more names, some crossed out.

And then she saw a line that made her stomach lurch.

Samuel transferred to Mr. Grayson, December payment toward debts.

Transferred. Like a chair. Like a horse.

Esther remembered Samuel being marched away three weeks earlier, his wife screaming until an overseer threatened her with the whip. Esther remembered the way the baron hadn’t even looked up from his porch.

In the ledger, Samuel was a number. A solution to a debt.

Esther stared at the paper until her eyes stung.

This wasn’t just hypocrisy.

It was arithmetic with human lives.

She took the shawl, hands shaking, and left the office, closing the door softly behind her.

That night in her cabin, Esther sat in the dark and listened to crickets sing like they didn’t know the world was wrong.

She thought of Clara’s green eyes.

She thought of the baron raising a glass to “blood” while his blood was priced and traded.

And she realized something else, sharp as a blade:

If the baron was willing to sell his own children to cover debts, then none of them were safe. Not Clara. Not Jacob. Not Ruth. Not anyone who carried his face.

Esther had survived by keeping her head down, by making herself invisible, by swallowing anger until it turned into something quiet and heavy.

But now that anger had a shape.

Now it had names.

The Dinner Party

November arrived with cooler air and sharper edges. The rice harvest filled the plantation with a bustle that felt almost celebratory if you ignored the exhaustion, the swollen feet, the way bodies moved as if they were borrowed and already overdue.

The baron hosted a grand dinner party, inviting politicians from Charleston and planters from neighboring estates. The big house glittered with candles and polished silver. Music floated from the parlor. Laughter rolled down the halls.

Esther moved through the dining room carrying plates and pouring wine, trained to be invisible.

Catherine wore a gown the color of deep burgundy, her hair pinned in careful curls. Thomas sat at the table, still a little thin from his illness, but well enough to smile politely when spoken to. The baron drank heavily, his cheeks flushed with pride and liquor.

He stood near the end of the meal, glass raised.

“To family,” he declared. “To blood. To legacy. Everything I do, I do for my son. Nothing matters more.”

The guests cheered and raised their glasses, the room sparkling with agreement.

Esther stood against the wall holding a silver tray, her fingers gripping the edge so hard her knuckles ached.

Family. Blood. Legacy.

She thought of Clara upstairs, emptying chamber pots. She thought of Jacob branded with the Riverside mark like cattle. She thought of Ruth learning to keep her laughter small so no one would accuse her of joy. She thought of Samuel, sold away like furniture.

And something inside Esther snapped, not loudly, not in a way anyone could see, but in a way that changed the shape of her breathing.

She looked at the baron’s smiling mouth and thought, You can say blood in a room full of people who benefit from your lie. But you cannot say it to the children you chained.

That night, after the guests had gone and the house exhaled into silence, Esther walked toward the kitchen house where Clara was scrubbing pots by lamplight.

Clara’s hands were raw. Her shoulders slumped with fatigue. She looked up as Esther entered, wary.

Esther lowered her voice. “You know, don’t you.”

Clara froze. “Know what?”

Esther swallowed. “About him. About why you look the way you do.”

Clara’s eyes flicked toward the door as if fear might walk in. Then she nodded, slow, resigned.

“My mama told me before she died,” Clara whispered. “She said he came to her cabin for years. She said… I got a brother in the big house.”

Thomas.

Clara said his name like it tasted bitter.

Esther felt grief move through her like a wave. “It shouldn’t be like this,” she said, the words small and fierce.

Clara let out a humorless laugh. “It is like this. It changes nothing. He’ll never claim us. We still property.”

Esther leaned closer. “What if everybody knew?”

Clara’s eyes went wide. “You can’t.”

“They already know,” Esther murmured. “They just don’t say it out loud.”

Clara shook her head, voice trembling. “They’ll kill you.”

Esther stared at Clara’s hands, at the blood in the cracks. “They already killing us,” she said, soft. “Every day. Just slower.”

The silence between them felt heavy as stone.

Then Esther made her choice.

Not because she believed it would fix everything.

But because she could no longer live inside a lie that was crushing children.

The Whisper Network

White society in Charleston ran on gossip the way a mill ran on water. A rumor, once set loose, could grind reputations into dust.

Esther didn’t have access to parlors or printing presses. But she had something slavery could never fully control: human connection.

On Sundays, when the Whitmores attended church in town, the plantation briefly rearranged itself. Enslaved people were watched, but the tight grip loosened just enough for messages to move.

There was a free Black seamstress in town named Miss Lila Freeman, a woman who did mending work for plantations because it kept her alive and kept her near information. Esther had seen her before, had traded quiet words while pinning fabric.

Esther approached her outside the church yard, heart pounding hard enough to make her dizzy. She kept her voice low, her face neutral.

“I need a message carried,” Esther said.

Miss Freeman’s eyes sharpened, alert. “A message to who?”

“The mistress’s cousin,” Esther replied. “The one visiting from Virginia. The one who loves… conversation.”

Miss Freeman studied Esther’s face, reading the danger there. “You sure you want that kind of conversation?”

Esther’s throat tightened. “I want the kind that can’t be unsaid.”

Miss Freeman took a small scrap of paper Esther had hidden in her sleeve. She didn’t open it. She didn’t need to. The weight of it was enough.

“All right,” she said quietly. “But you understand what you doing.”

Esther nodded. “I do.”

The message was simple.

Ask Baron Whitmore about the green-eyed children in his quarters. Ask which of his property shares his blood.

Gossip loves certainty. It loves something specific enough to point at.

Within two weeks, Charleston was humming.

At first, people laughed behind gloved hands. Men made jokes in clubs. Women leaned close over tea cups. But then someone remembered Jacob’s jawline. Someone remembered the baron’s late-night visits. Someone remembered a green-eyed girl carrying trays at a dinner party and thought, Wait.

Once a rumor attached itself to images, it stopped being rumor.

It became scandal.

By early December, Catherine Whitmore’s smile had started cracking at the edges. She caught herself staring too long at Clara. She began snapping at servants for reasons that made no sense. Thomas, sensing something wrong, grew quiet.

And one evening, after a tense dinner, Catherine told Thomas to go upstairs and then marched into the baron’s office, shutting the door hard enough to rattle frames on the wall.

Esther was in the hallway with a basket of linens, close enough to hear muffled voices.

Catherine’s voice rose first, sharp with disbelief. “Is it true?”

The baron’s reply was lower, controlled. “People talk.”

“Don’t do that,” Catherine snapped. “Don’t turn this into people talk. Look at me and tell me.”

Silence, heavy.

Then Edward Whitmore spoke in a tone that sounded like surrender wearing arrogance. “It is what it is.”

Catherine made a sound Esther had never heard from her before, raw and animal, like something breaking loose. “In my house,” she hissed. “In my bed you speak of honor and family, and in the quarters you—”

The baron’s voice hardened. “Mind your voice.”

“I will not,” Catherine spat. “Those are your children.”

Another silence.

Then the baron, furious now, said the line that made Esther’s skin prickle:

“They are slaves. That’s all they’ve ever been.”

Esther closed her eyes. Somewhere inside her, grief and rage folded together like storm clouds.

Catherine’s voice went quieter, trembling with something like devastation. “Free them,” she whispered.

The baron laughed once, bitter. “Do you have any idea what you’re asking? Their value alone—”

Catherine’s words cut like glass. “Their value? They are people.”

“They are a problem,” the baron snapped. “And you will not ruin everything I built.”

The argument exploded after that, shouting spilling into the hall. Thomas came halfway down the stairs, eyes wide, and Esther saw the moment childhood ended for him, not with a bruise but with a truth.

By morning, Catherine had made her own decision.

She packed trunks. She took Thomas. She left Riverside for Virginia, returning to her family plantation and filing for legal separation, an act so scandalous in 1841 it made Charleston gasp.

The baron’s reputation collapsed like a house with rotten beams.

But in the quarters, nothing changed quickly enough to look like justice.

Clara still scrubbed floors. Jacob still worked the stables. Ruth still woke before dawn.

The scandal had damaged the powerful.

But power had thick skin.

The Price of Speaking

The baron never learned Esther’s name was attached to the whisper that began the ruin. He suspected. He watched the quarters with narrowed eyes. He drank more. He prowled the big house halls like a man haunted by his own reflection.

He stopped selling certain people. Not out of kindness, but out of panic. If his “mixed parentage” children vanished into other plantations, their resemblance might turn into someone else’s scandal. Keeping them close was safer.

It was a small, selfish mercy.

And it still mattered.

Jacob stopped being whipped for minor mistakes. Clara was moved into lighter house work. Ruth was allowed to stay near her mother.

Esther watched these changes with a bitter understanding: slavery could offer crumbs and call it generosity, and the world would applaud.

The baron’s health began to fail in early 1842. Some said his liver was ruined by drink. Others whispered it was God. Esther knew it was simpler and more complex at once.

A man can outrun consequences for years.

But he can’t outrun himself.

Edward Whitmore died in March in his own grand house, surrounded not by friends but by the people he owned. Catherine did not return. Thomas did not return. Charleston society sent polite condolences that smelled like relief.

When the will was read, it shocked everyone who still bothered to listen.

Riverside was left to Thomas.

But there was also a clause, carefully written, legal language trying to hide a confession:

Certain persons of mixed parentage on the estate were to be treated with “special consideration,” not sold, not separated from their families, not subjected to extreme punishment.

The baron could not free them. Could not name them. Could not, even in death, speak the truth plainly.

But he left behind a loophole of conscience.

Thomas, fourteen and shaped by his mother’s fury, ignored it when the time came. He inherited Riverside later and ran it the way he’d been taught: with distance, with entitlement, with a kind of cold that made love into something conditional.

Clara remained enslaved.

Jacob remained enslaved.

Ruth remained enslaved.

Esther remained enslaved.

And yet the secret had changed the air, permanently.

Because once you see hypocrisy clearly, it never goes back to blending into wallpaper.

A Different Kind of River

Years moved forward the way rivers do: steady, indifferent, unstoppable.

War eventually tore through the nation like a reckoning. Men marched. Flags changed. Laws shifted. But on plantations, freedom didn’t arrive like a bell. It arrived like a door opening slowly, with people terrified there might be another door behind it.

When the Emancipation Proclamation came in 1863, it was a promise as much as a reality, complicated by geography and guns. But by 1865, when the war ended, Riverside could not hold on to bondage the way it once had.

Esther was fifty-six when she became free.

She stood outside her cabin with paper in her hand, words declaring what her bones already knew: she was not property. She was not a number. She was a person.

Her hands shook as she read.

Clara, older now, stood beside her, eyes bright with something that looked like grief and wonder intertwined.

“What we do now?” Clara whispered.

Esther looked at the big house, its white columns gleaming like it was innocent. She looked at the river in the distance, still moving, still carrying its secrets.

“We live,” Esther said simply. “And we tell the truth.”

They stayed at Riverside for a time because leaving is expensive, and freedom doesn’t come with a wagon of supplies. They worked land as paid labor. They helped build a schoolhouse with other freed families. Clara married a man who treated her name like it mattered. Ruth grew into womanhood without a bill of sale hanging over her future.

Esther didn’t travel far. Riverside was the only map her life had ever been allowed to know. But she changed the way she walked on it.

She walked like she belonged to herself.

Esther died in 1865, months after emancipation, free long enough to taste what had been denied her. Some would call that tragic. It is. But it is also true that not everyone gets even that.

Clara lived until 1891, long enough to see children and grandchildren born into a world where no one could legally own them. She never stood in public and named Baron Whitmore as her father. Some names are not worth inheriting.

But her descendants kept the story alive, passed down like a hard-earned heirloom.

Not because it was scandal.

Because it was proof.

Proof that a woman once jumped into a river and saved a boy who belonged to the people who claimed she didn’t belong to herself.

Proof that she saw a secret stitched into faces and refused to pretend she was blind.

Proof that sometimes the bravest thing a person can do is not survive quietly, but speak, even when the world has built an entire economy on keeping you silent.

Riverside, in one form or another, still stands today. Places like it have been turned into museums with manicured paths and polite tour guides who talk about architecture and “a bygone way of life.”

But history is not wallpaper.

It has fingerprints.

And if you listen carefully enough, you can still hear a river moving through the low country, carrying a truth that refused to drown.

THE END

News

“He removed his wife from the guest list for being ‘too simple’… He had no idea she was the secret owner of his empire.”

Julian Thorn had always loved lists. Not grocery lists, not to-do lists, not the humble kind written in pencil and…

HE BROUGHT HIS LOVER TO THE GALA… BUT HIS WIFE STOLE ALL THE ATTENTION….

Ricardo Molina adjusted his bow tie for the third time and watched his own reflection try to lie to him….

Maid begs her boss to wear a maid’s uniform and pretend to be a house maid, what she found shocked

Brenda Kline had always believed that betrayal made a sound. A scream. A slammed door. A lipstick stain that practically…

Billionaire Accidentally Forgets $1,000 on the Table – What The Poor Food Server Did Next Shocked…

The thousand dollars sat there like a test from God himself. Ten crisp hundred-dollar bills fanned across the white marble…

Baby Screamed Nonstop on a Stagecoach Until a Widow Did the Unthinkable for a Rich Cowboy

The stagecoach hit a rut deep enough to feel like the prairie had opened its fist and punched upward. Wood…

“I Never Had a Wife” – The Lonely Mountain Man Who Protected a Widow and Her Children

The knock came like a question without hope. Soft, unsure, but steady, as if the hand outside had promised itself…

End of content

No more pages to load