THE OAK THAT KEPT FOUR NAMES

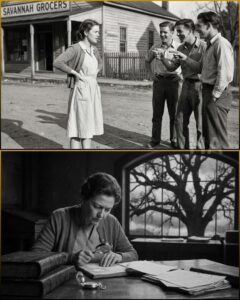

In the summer of 1963, when Savannah’s heat sat on the streets like a hand that refused to lift, Margaret Wilson learned a local rule that no archive ever writes down: the older the wound, the more politely people will smile while they hide it.

She came from Athens with a scholarship, a stack of sharpened pencils, and a dissertation proposal that sounded harmless in a committee meeting. Unexplained disappearances of enslaved women in antebellum Savannah. It was the sort of title that made professors nod thoughtfully and donors feel sophisticated. But the moment she said the name “Foresight” to a librarian with silver hair and a careful mouth, the woman’s eyes shifted toward a window as if the glass might supply an alternative answer.

“There was an estate,” the librarian said, rearranging a pile that did not need rearranging. “Cotton. The Harringtons. It’s… not there now.”

Margaret already knew that part. She had taken a bus out past the historic district, past the squares tourists photographed as proof that history could be pretty, and she had stood at the edge of a shopping center parking lot while cars rolled over land that once held a manor house, gardens, quarters, a kitchen yard, and thirty human lives counted as property. Someone had planted two ornamental shrubs near a concrete curb, and a bronze marker declared, in words as clean as a freshly laundered lie: Site of Forsythe Estate, circa 1830 to 1870. Cotton plantation owned by the Harrington family.

The marker did not mention a woman. It did not mention four children. It did not mention an oak tree that had once held the eastern garden in its shadow, or the way that shadow had lengthened, year by year, with each small burial. It certainly did not mention the silence of the mother who had watched the digging, watched the covering, and stayed alive anyway, long enough to vanish.

Margaret had expected resistance from time itself: missing pages, faded ink, fire and humidity, the usual thief’s toolkit. She did not expect resistance from the living, from families who still attended the right churches and still owned the right names. That first week, she chased references like a hound, inhaling dust at the courthouse and the historical society, copying ledger entries that reduced an entire body to a line of cursive and a sum.

January 1835: Female, 22, domestic skills, acquired.

Winter 1835: Bowmont, Elellanena.

Master: Thomas Harrington, forty-six, recently widowed.

The ink did not say why he chose her, but the margins of the world whispered what the page refused.

On a humid afternoon, Margaret found the caretaker’s journal from Foresight Estate, preserved because it had been forgotten in an attic and therefore spared the mercy of deliberate cleaning. The handwriting was neat, brisk, as if the writer believed order could be made out of everything, even people.

January 12th, 1835. New arrival today. Master seems unusually attentive to her quarters. Requested the room adjacent to the kitchen be prepared with particular care. Unusual for January.

Margaret traced the sentence with her finger and felt the small chill that sometimes rose behind her ribs when a record contained just enough humanity to make its cruelty sharper. A room by the kitchen, warmed, watched, and chosen not for comfort but for convenience.

She copied the entry, then closed her notebook and sat in the quiet of the reading room long enough to hear what the building’s air-conditioning was trying to drown out: the steady insistence of the past, tapping from inside the walls like someone trapped.

That night, in her rented room above a bakery, Margaret began to write the story she could not prove yet but could not avoid either. She wrote it the way a person sets a table for a guest who has been starved for centuries: carefully, respectfully, refusing to rush.

She began, not with the master, but with the woman.

Elellanena Bowmont arrived at the Savannah market in winter light that made everything look bleached, as if the sun itself wanted to forget what it had seen. She had been brought from inland, or perhaps from the coast, depending on which rumor one believed. Parish records later described her as “mixed,” a word that made officials comfortable because it reduced ancestry to a convenient blur, and described her “exceptional domestic skills,” which was also convenient because it avoided describing her face.

The truth of her beauty was the kind that made men in power feel entitled and women feel wary, the kind that pulled attention the way a bright ribbon pulls a child’s hand. She kept her eyes down, not from submission, but from calculation. Her grandmother had taught her that a gaze can be a doorway, and doorways in captivity were dangerous things.

At twenty-two she already carried a history that no ledger could hold: the smell of salt marshes, the taste of bitter greens when meat was scarce, a lullaby in a language her mother had tried to keep alive between labor and punishment. She also carried knowledge that did not look like knowledge to the people who bought bodies. She could read herbs the way some people read scripture, could tell which leaves soothed fevers and which ones, handled wrongly, could make a heart stumble. Her grandmother called such knowledge a small knife, not for harming others, but for carving out a sliver of choice where choice was forbidden.

Thomas Harrington watched her from the shadowed side of the market like a man choosing furniture, yet his grief made his gaze hungry in a way grief often does. His wife had died of consumption, and the house that had once held her quiet authority now held only his loneliness and the echo of his name. He had no daughter to soften him, no son to distract him, and no appetite for the sermons that told him suffering purified. He wanted a remedy. He wanted the world to offer him something that looked like comfort.

He had been inspecting new arrivals for weeks, as if shopping could replace mourning, as if a purchase could plug the hole death had punched in his life. When he chose Elellanena, the transaction was recorded with a line of cursive and a sum, and she became, in official terms, his.

In practical terms, she became the room by the kitchen, made “with particular care,” which meant she became close enough to serve and close enough to be summoned without witnesses needing to be called.

At first, outsiders saw nothing unusual. Foresight Estate stood three miles east of Savannah’s historic district, white columns bright against Georgian sky, gardens pruned into obedient shapes, cotton fields spreading like a promise made with someone else’s blood. The enslaved worked in a system of sunrise and overseer whistles, their bodies measured in output, their names spoken mostly when someone needed something done.

Elellanena worked among them, carrying trays, scrubbing floors, learning the household’s rhythm the way a drummer learns a song. Yet within months, her assignments shifted like a door sliding on oiled hinges. She was taken from the field hands’ orbit and placed in direct service to Thomas Harrington. She poured his coffee. She laid out his shirts. She stood close enough to hear his breath change when he looked at her.

Mrs. Potter, the housekeeper, did not say much. A woman like Mrs. Potter could survive decades by turning her face into a mask. She ran the house with lists and keys, and she knew which truths were safe to speak only in her own mind. When Elellanena was given the kitchen-adjacent room, Mrs. Potter ordered linens brought, and her hands were steady, but her mouth stayed pressed tight, as if holding back words would keep the house from cracking.

The other enslaved saw the change and knew what it meant. Favor was just another name for exposure, and elevation in such a place could be a trap built from lace. Maria Wilson from the neighboring Wilks plantation later told her grandson that everyone knew what was happening at Foresight. “The master had taken a fancy,” she said, and her voice, even in the oral history recording, carried an old disgust, the kind that comes from watching someone be hurt in a way no one is allowed to name.

Elellanena wore finer fabric by autumn of 1836. Not a dress fit for a ball, but cloth that softened the eye’s suspicion. A pair of leather shoes appeared in the expense ledger. Then, most strangely, a small silver locket, purchased in town and tucked into Thomas Harrington’s personal Bible as if the object needed the blessing of scripture to cleanse what it represented.

He gave the locket to her one evening after supper, when the house had settled into its night hush and the servants moved like shadows. He did not call it a gift; he called it “a token.” He held it between thumb and forefinger, the silver catching firelight, and spoke as if he were generous.

Elellanena took it because refusing would have been a kind of war she could not win. The locket was cool, and its clasp bit her skin. She wore it beneath her collar, where no one could easily see it, and she learned to hate the way a small beautiful thing could feel like a chain.

The first time she became visibly with child, in the spring of 1837, no announcement was made. The plantation did not celebrate the way families celebrate. Dr. Samuel Thorne began to visit more often, his carriage wheels carving lines in the yard that the rain could not erase. His logbook later referred to “the delicate condition at Foresight,” and his prescriptions for tonics used language that pretended the body was a polite machine, not a woman’s life bent around another life forced into existence.

On November 18th, 1837, Elellanena gave birth to a girl.

Thomas Harrington named the child Caroline after his mother, and in his personal journal he wrote, Providence has blessed the house with new life today. She has her eyes. He did not write Elellanena’s name beside the baby’s. The property ledger did not list Caroline at all, as if omission could shape reality, as if an unrecorded child could be both possession and secret.

Elellanena held her daughter and felt the world split into two unbearable truths. One truth was simple and fierce: Caroline’s small weight against her chest created a tenderness that no whip could reach. The other truth was colder, with edges like broken glass: Caroline was born into slavery, into a life where her mother could be sold, where her body would be claimed by someone else’s law.

The room by the kitchen expanded. A rocking chair was purchased, a copper bathing tub, a small wooden cradle with linens. Mrs. Potter supervised the additions, her lips thin, and the other enslaved looked at the items with a mix of envy and dread, because special treatment was never free. It was payment taken in advance for a debt that would be collected later.

For several months, life held a fragile semblance of normal. Elellanena worked less, watched more. Thomas Harrington visited often, standing in the doorway of her room like a man unsure whether he was a father or an owner, and perhaps unsure which role embarrassed him more. He spoke softly to Caroline, and Caroline smiled, because infants have no concept of social hypocrisy. She recognized voice and warmth, not the rot under the floorboards.

In July of 1838, the fever came.

It began as a heat in Caroline’s skin, a restlessness in her small limbs, then a crying that turned hoarse. Dr. Thorne was summoned, and he brought powders and confidence. He spoke of humors and constitution, and he did what the era allowed, which was not enough. Elellanena sat with the child through the night, cooling her forehead with damp cloth, singing the lullaby her grandmother had carried across water and loss. By morning, Caroline’s breath had grown thin as thread.

On July 23rd, Caroline died at eight months old.

No death certificate was filed. The world did not require documentation when the dead were enslaved. Yet Thomas Harrington did something uncommon: he ordered a grave dug beneath an oak tree at the eastern edge of the garden. The oak’s branches spread wide, and in summer its leaves made a shade that looked almost gentle. The master stood nearby when the small body was lowered. He watched the earth cover what he had named, and his face tightened as if grief could be controlled through jaw muscles.

Elellanena’s grief was quieter than anyone expected, which made it more frightening. Mary Stillwell, a merchant’s wife visiting the estate, wrote to her sister in Charleston that she saw the young woman kneeling at the fresh grave, “completely still, making no sound.” She wrote that Mr. Harrington watched from the veranda without interrupting, and that when the mother finally rose, her face held no expression at all. Mary Stillwell said it chilled her to her core, because a woman without visible sorrow looked to her like a woman past fear.

Elellanena did not stop feeling. She simply stopped offering her feelings to a world that treated them as entertainment.

By winter of 1838, she carried another child.

This pregnancy came with fewer surprises. Her body had learned the brutal mathematics of survival: eat when food appears, sleep when sleep is permitted, hide what must be hidden. On May 3rd, 1839, she delivered a son, and Thomas Harrington named him James after his father. Again, the name entered private writing, not public record. Again, the room by the kitchen gained new purchases: a larger bed, extra linens, and, most ominously, a lock installed on the door.

Thomas Harrington called it protection. Elellanena recognized it as ownership made explicit.

James thrived at first. His lungs were strong. He ate greedily, as if he intended to consume the world before it could consume him. For nearly ten months, there was laughter in the room by the kitchen, small and rare, and Elellanena sometimes allowed herself to pretend that love might be an anchor.

In March of 1840, James developed a cough that deepened into an affliction that rattled his chest like a loose coin in a tin. Dr. Thorne came, then came again, bringing syrup and assurances. He listened with his stethoscope and spoke in words that made disease sound like fate, as if naming the illness could absolve the system that helped create it. The dampness of the room, the exhaustion in Elellanena’s body, the work she had done with an infant tied to her back because labor did not pause for motherhood, all of it pressed its thumb on the scale.

James died on March 15th, 1840.

Thomas Harrington ordered another burial beneath the oak, beside Caroline. No marker was placed, but the gardener noted white roses planted at the site afterward. The roses were Elellanena’s act, small and stubborn. White, because in her grandmother’s stories white meant passage, and also meant insistence, the refusal to let a grave be swallowed by ordinary ground.

Three days after the burial, Thomas Harrington left for Atlanta on business. Two weeks passed. In that absence, something in the house shifted, a hinge loosening, a crack forming. The estate ledgers did not record it, because ledgers do not record the sound a woman makes when she realizes the world has no intention of sparing her.

When Thomas returned, he wrote, Returned to find matters at home in disarray. E confined to her quarters. Mrs. Potter reports extreme melancholy and refusal of food. Dr. Thorne consulted. Situation requires careful management.

Laundry records showed increased linens from Elellanena’s room. Meals were delivered instead of collected. The house moved around her as if she were a dangerous object that might shatter if touched.

Dr. Thorne prescribed laudanum “for nerves,” and the medication softened the edges of consciousness in a way that made time slippery. Some days Elellanena woke unsure whether she had slept for hours or for years. In those blurred spaces, she heard the oak tree in her mind, heard leaves whisper as if carrying voices. She began to understand why some spirits linger, not because they are supernatural, but because grief is a force that refuses to stay contained.

By summer she recovered enough to resume some duties. The world insisted on motion. The cotton demanded tending. The house demanded polishing. Elellanena moved as required, but inside her, something had changed shape. She no longer expected fairness. She expected only consequence.

In September 1840, she was with child again.

This third pregnancy coincided with a new kind of agitation in Thomas Harrington, noted even by business associates who came to talk contracts and prices. Frederick Montro, a cotton broker, wrote that Harrington interrupted meetings to check on matters in the house and inquired about physicians in Charleston “more skilled than local practitioners.” His concern, Frederick noted, interfered with his judgment in business affairs, which was a polite way of saying the master had become haunted by what he had created.

He converted a small sitting room near his bedroom into a birthing chamber. He hired Mrs. Sarah Blackwood, a midwife from Savannah, to reside at the estate for the final month. He paid her from the estate payroll like a piece of equipment, yet he treated her as if she were a priest capable of bargaining with God.

Mrs. Blackwood later told her daughter only that she had never seen a woman so silent in suffering, nor a man so desperate in hope.

On April 10th, 1841, Elellanena gave birth to a third child, another girl. Thomas named her Elizabeth.

This time, he called for Reverend William Stokes from St. John’s Episcopal Church to perform a private baptism. The church register recorded the event with unsettling precision and an equally unsettling absence: Elizabeth Harrington, daughter of Thomas Harrington, baptized at Foresight Estate, April 11th, 1841. No mother’s name.

Thomas Harrington began to write daily observations of Elizabeth as if recording her could protect her. He noted her first smile, the changing color of her eyes from blue to brown, the way she seemed to recognize his voice. He commissioned a portrait from a Savannah artist, an infant rendered in paint with solemnity that felt almost like an apology. The portrait’s existence would survive longer than the child it tried to honor.

In August 1841, Elizabeth began to fall ill.

Thomas summoned Dr. Thorne immediately, then called for Dr. Marcus Whitfield from Charleston, a man known for childhood diseases, as if expertise could wrestle death to the ground. The doctors bent over the small body, their hands smelling of camphor and authority. They spoke in low voices that tried to soften inevitability, but the truth of the era was that medicine often arrived like a lantern after the bridge has collapsed.

Elizabeth died on August 17th, 1841, at four months old.

Thomas Harrington spent an extraordinary sum on a small marble headstone. It bore only the name Elizabeth and the dates of birth and death. A formal marker, as if stone could compensate for what law had refused: legitimacy, safety, a future.

Elellanena watched the burial beneath the oak, watched the earth fold over the third small body, and she felt something in her chest go quiet, not from numbness but from decision. She had carried three children into the world, and each time the world had taken them back. Somewhere in the taking, she began to ask the question that official history hates because it refuses neat categories: when every option is cruelty, what does mercy look like?

Two days after Elizabeth’s death, she wrote in her hidden journal, in handwriting that did not apologize for existing:

The third has returned to the stars. Master T rages against God and fate. He had such hopes for Elizabeth. I look at the one growing inside me now, my fourth and final burden, and I know what I must do. There are kinder doorways to the next world than the ones this place provides. My grandmother taught me how to find them. May she forgive me. May they all forgive me.

The words did not explain everything. They did not name an act. They did not confess the way white society preferred confessions, with tidy guilt and tidy punishment. They simply revealed a mind pressed against a wall, searching for any crack that could be turned into a door.

On August 20th, Thomas Harrington left for Savannah on business. He returned unexpectedly the same evening, as if the city’s air could not hold him. The next morning, Elellanena was gone.

The estate organized a search in the way estates organized things: overseer orders, men with boots moving through woods, neighboring plantations notified. No authorities were contacted, which mattered. If Thomas Harrington believed her disappearance was merely theft of his property, he could have invoked law. Instead he offered a reward to his overseer if she was returned discreetly. Discretion meant fear. Discretion meant the master had something to hide.

After three days, they found her in the abandoned hunting cabin at the far edge of the property, four miles from the main house. She was unharmed, but unwell in mind, the overseer’s report said, using language that sounded concerned while denying her the dignity of being understandable. She was brought back under watch.

What followed was confinement disguised as care. Her former room was emptied. She was moved to a third-floor room in the main house, away from the kitchen, away from the yard, away from any human being who might offer a whispered kindness. A special lock was purchased. The window was boarded from the outside. Dr. Thorne visited twice weekly, his log reducing her to symptoms: sedated, refuses food, speaks of children calling from beneath the oak.

During those weeks, Elellanena’s body grew heavier with the fourth child. Her mind, when not clouded by laudanum, returned to the oak again and again, because grief has its own magnetism. She saw Caroline’s small hands in memory, James’s hungry smile, Elizabeth’s changing eyes. She remembered the lock on her door and the way Thomas Harrington’s hope always arrived hand in hand with his control.

Thomas Harrington’s own journals grew sparse. A man can write many pages about the weather and none about his own monstrous entitlement. Yet in his silences, the estate’s servants felt the atmosphere tightening, as if the house itself had begun to hold its breath.

On the night of October 11th, 1841, without a midwife present, Elellanena delivered a stillborn male infant.

Dr. Thorne was called after the fact. He arrived to find the child already wrapped, prepared for burial, as if the house had rehearsed the procedure. Elellanena lay weak, blood lost, eyes unfocused. Dr. Thorne advised removal to a hospital in Savannah. Thomas refused, insisting on home treatment, insisting, perhaps, that the fewer witnesses outside the estate, the safer his standing would remain.

Dr. Thorne wrote privately, I fear the outcome is predetermined. I record this account to clear my conscience.

In the morning, Elellanena was again sedated, and the fourth small body was placed beneath the oak without ceremony. The oak’s roots, hungry and innocent, grew around bones it did not understand.

October 12th, 1841, Thomas Harrington wrote one line: It is finished. May God have mercy on us all.

The following day, housekeeping records noted the third-floor room was emptied and cleaned.

Elellanena Bowmont disappeared from the written record.

In the years after, Thomas Harrington did not remarry. His business declined. He became erratic, drawn to Savannah and Charleston, leaving the estate under his cousin’s management. Debts mounted. In 1850 he sold nearly half the enslaved individuals. In 1858 he died at sixty-nine, leaving the estate to his cousin’s son with one strange stipulation: the oak tree in the eastern garden was never to be cut down, and the surrounding area was to remain undisturbed.

A man who believed he could own bodies still feared what lay beneath a tree.

Margaret Wilson, writing in 1963, paused when she reached that point in the record. She had already learned that history is rarely a clean narrative and almost never a fair one, but the disappearance sat in her mind like a stone. People vanish for many reasons. People are made to vanish for many more.

Weeks later, she found something that did not belong in ledgers: a letter, copied into an archival file from St. John’s Episcopal Church. It had been discovered behind a vestry wall during renovations, hidden like a shame too heavy to carry openly. The handwriting belonged to an assistant, Reverend James Sullivan, and the date made Margaret’s skin prickle.

October 14th, 1841.

Sullivan wrote of Elellanena being brought to the church “more dead than alive” by Mr. Harrington himself, under the claim she had attempted self-harm. Sullivan admitted the truth was darker: she had been kept under lock and key since the stillbirth, and when sedation was removed she became “unmanageable in her grief.” Harrington feared she might reveal truths about the children that would ruin his standing. Sullivan had been asked to arrange immediate passage on a vessel departing for New Orleans.

Margaret read the line twice, then a third time, because she had learned that the body sometimes recognizes truth before the mind is ready to accept it.

The letter included one sentence from Elellanena herself, recorded by a man who felt his conscience cracking: “All four sleep beneath the oak. I sang to them as they passed. It was the only kindness I could offer.”

And then another sentence that made Margaret close her eyes and feel the room tilt: “The sin was not mine, Father. The sin was bringing them into this world knowing what awaited them. I simply opened the door to a better place.”

The letter did not prove what happened. It did not name which deaths were natural, which were hastened, which were forced. It only revealed that the people around Elellanena were terrified of the story she could tell, and that terror had the power to move her like cargo.

Shipping records, if one looked hard enough, contained a line that matched the date. A merchant vessel, the Carolina Star, bound for New Orleans. Among the cargo: female negro infirm. On October 17, the log noted, the unnamed passenger died at sea and was buried in the Atlantic.

Margaret imagined the ocean swallowing a woman who had spent her whole life being swallowed by other people’s appetites. She imagined the waves closing over a body with no grave, no marker, no family allowed to mourn properly. She imagined the Atlantic not as a romantic expanse, but as a final erasure.

In her notebook, Margaret wrote a sentence she did not know she was writing until it was already there: If they could not let her live, they could at least not let her speak.

That was the point where her research began to attract attention.

Doors that had been open became closed. Requests for documents were delayed. A man at the historical society, friendly the first time she met him, began to treat her like a nuisance. Then she received anonymous notes slipped under her boarding-house door, the paper cheap, the message blunt: Focus your scholarly attention elsewhere.

Margaret was not a fragile person, but she was also a young woman in the South with no family name to protect her, and the past had a way of reaching forward through descendants who still believed silence was inheritance. She finished her dissertation in 1967, binding it in plain covers, filing it in university archives, and leaving Savannah with a feeling that she was abandoning someone on the side of the road.

Yet the story had already taken hold inside her. It followed her to New England, where she taught at a small college and pretended to focus on safer topics. Sometimes, in the middle of grading, she would look up and see, in her mind, an oak tree spreading its branches over four small graves. Sometimes she would wake from a dream of white roses.

In 1872, long after Margaret was not yet born and Elellanena was long dead, the estate land was sold to a lumber company. Despite the will’s stipulation, the oak was cut down. Workers clearing the garden area found small remains beneath the roots, not three sets as expected, but four. The additional set was newborn in size, with no coffin. A rumor traveled through Savannah, then faded as rumors do when the powerful prefer forgetfulness.

In 1968, a small silver locket was discovered six feet beneath ground near where the oak had stood, its clasp corroded but still stubborn. Inside was a braid of dark hair and a tiny portrait painted on ivory of a woman with features suggesting mixed ancestry. The initials on the back were barely legible, but they were there: E.B.

The locket ended up in the Savannah Historical Society Museum, small enough to be overlooked by visitors hunting for romance and architecture. Margaret, back in town briefly for a conference, stood before the display case and felt her throat tighten. The locket was not proof of innocence or guilt. It was proof of existence, which in a system designed to erase existence was its own kind of rebellion.

Decades later, in 2003, a historian gained access to Sullivan’s confession and published a paper that stirred the story awake again. The same year, critics began asking why certain artifacts remained in “special collections” requiring permission to view, as if pain must be kept behind velvet ropes.

In 2012, ground-penetrating radar surveyed the shopping center’s eastern section and revealed an underground chamber, fifteen feet below current surface. Archaeologists excavated carefully, and inside they found a wooden chest, deteriorated but intact. The chest held a child’s knitted cap, four small cloth dolls arranged in a row, a hand-copied page from a prayer book, and a journal bound in faded cloth.

Some pages had rotted. Some words survived.

The handwriting matched the ivory portrait. One entry, dated July 25th, 1838, read:

They have put Caroline beneath the oak. Master T says it is a mark of special favor not to be with the others beyond the north field. He does not understand that the ground consumes us all the same, favor or no favor. Is this what mothers become in this place? Women who speak to trees because their children lie beneath them.

Another entry, dated March 18th, 1840, read:

The white doctor says James’s lungs were weak. What he does not say is why. The dampness of our room. The work I did with him strapped to my back. These are the true causes, but they are not written in medical books. I do not weep anymore. Tears are a luxury belonging to those who expect the world to be fair.

And the entry dated August 19th, 1841, the one that scholars argued over, the one that refused to stop burning:

There are kinder doorways to the next world than the ones this place provides.

In 2015, a descendant of the Harrington family, Katherine Harrington Wells, established a memorial foundation. Some called it an attempt at absolution. Others called it overdue honesty. At the dedication of a new marker that finally included Elellanena Bowmont’s name and acknowledged four children buried there, Katherine said they could not change the past, but could change how they remembered it, how they honored those who suffered, and how they understood their humanity and agency even within a system designed to deny both.

A small contemplative garden replaced the oak’s absence. Four small stone markers sat in a semicircle. At the center stood a bronze sculpture of a woman, face tilted upward, arms empty but slightly raised, as if releasing something to the sky.

On some mornings, anonymous visitors left white roses at the base.

Margaret Wilson, now old, visited once, quietly, without announcing herself. She walked the semicircle slowly, reading the stones, letting the names that were not recorded in ledgers settle in her chest. She stood before the sculpture and thought of a woman in 1841 who had been forced into impossible choices and then denied even the dignity of a grave.

Margaret did not claim to know the full truth. No one could. The system had been designed to obscure, to scatter evidence, to turn pain into rumor and rumor into silence. What remained were fragments: a lock, a journal line, a baptism record without a mother’s name, a confession letter hidden behind church walls, a shipping log that reduced a dying woman to “cargo,” and a locket that kept initials like a heartbeat.

As the sun sank behind the shopping center and its bright signs flickered on, Margaret watched families push carts, teenagers laugh, workers sweep up trash, ordinary life unfolding on top of extraordinary sorrow. She understood, with a clarity that made her eyes sting, that memorials do not resurrect the dead, but they can interrupt the habit of forgetting.

Before she left, she placed a single white rose on the ground, not as a verdict but as a recognition.

If Elellanena had ended her children’s lives, Margaret thought, then it had been a mercy born from horror, a love twisted by a cage. If Elellanena had only watched them die from illness and neglect, then the cage itself had killed them, slowly, politely, and without leaving fingerprints. Either way, the world that forced her into those boundaries was guilty beyond any individual act, because it made motherhood into an ordeal and love into a liability.

She imagined the Atlantic at night, water dark as ink, and somewhere beneath that restless surface, a woman’s body returning to the elements that could never be owned. She imagined the oak tree that once stood as a witness, cut down despite a will, because even the descendants of power had feared what roots might hold. She imagined the journal hidden underground, protected by earth the way secrets sometimes are protected, waiting for someone to dig not for profit but for truth.

Margaret turned to go. Behind her, the bronze woman held her empty arms to the sky, forever mid-release, forever refusing to be bent into a simple story.

And on the plaque near the garden’s exit, a line from the recovered journal had been carved for anyone willing to read, for anyone willing to let memory do what law once refused:

What they took from us in life, we reclaim in memory. And memory, once awakened, is a force that cannot be enslaved.

The parking lot lights hummed. Cars moved like slow insects. The city’s evening sounds gathered. Yet in that small garden, for the length of a few breaths, a woman who had been meant to leave no mark was spoken aloud, not as property, not as a rumor, but as a human being whose love and suffering were too large to be contained by any ledger.

In the absence of justice, remembrance served.

And the oak, though gone, still held four names in the air, as if the world had finally learned to listen.

News

All Doctors Gave Up… Billionaire Declared DEAD—Until Poor Maid’s Toddler Slept On Him Overnight

The private wing of St. Gabriel Medical Center had its own kind of silence, the expensive kind, padded and perfumed…

Mafia Boss Arrived Home Unannounced And Saw The Maid With His Triplets — What He Saw Froze Him

Vincent Moretti didn’t announce his return because men like him never did. In his world, surprises kept you breathing. Schedules…

Poor Waitress Shielded An Old Man From Gunmen – Next Day, Mafia Boss Sends 4 Guards To Her Cafe

The gun hovered so close to her chest that she could see the tiny scratch on the barrel, the place…

Her Therapist Calls The Mafia Boss — She Didn’t Trip Someone Smashed Her Ankle

Clara Wynn pressed her palm to the corridor’s paneled wall, not because she needed the support, but because she needed…

Unaware Her Father Was A Secret Trillionaire Who Bought His Company, Husband Signs Divorce Papers On

The divorce papers landed on the blanket like an insult dressed in linen. Not tossed, not dropped, not even hurried,…

She Got in the Wrong Car on Christmas Eve, Mafia Boss Locked the Doors and said ‘You’re Not Leaving”

Emma Hart got into the wrong car at 11:47 p.m. on Christmas Eve with a dead phone, a discount dress,…

End of content

No more pages to load