No one who crossed the threshold of Oak Hollow on the night of December 14, 1873, believed they were walking into their last supper.

The mansion sat on a bend of the Mississippi in St. Marais Parish, fifteen miles upriver from New Orleans, where the river moved like dark silk and carried every secret downstream with the same patience it carried driftwood. Gas lamps flickered behind tall windows. Carriages rolled over crushed shell in the drive. The air smelled of cane sweetness and wet earth, the perfume of a place that had learned to make money from anything that could be pressed, boiled, and sold. Inside, imported crystal caught the candlelight and scattered it in splinters across polished mahogany, as if the room itself had been cut from a diamond and was trying to pretend it wasn’t.

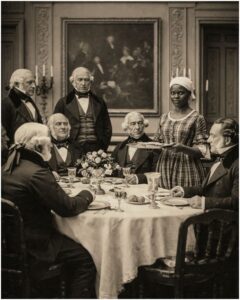

Eleven men, all between forty and sixty, arrived dressed as if the war had never ended, as if the world hadn’t changed its laws while they weren’t looking. They called one another “Colonel” out of habit and politics, and because titles, like land, were hard to surrender once your hands had closed around them. They owned plantations that reached past the tree line and into the horizon’s haze. In the old days, they had owned people outright. Now, in Reconstruction’s thin daylight, they owned them through contracts, debts, and courts that leaned in their favor. They laughed too loudly, slapped one another’s backs too hard, and congratulated themselves on the season’s sugar harvest as though the cane had grown from their virtue.

In the back of the house, beyond a corridor that smelled faintly of beeswax and cigar smoke, the kitchen glowed with heat and motion. Iron pots steamed. Knives struck cutting boards in steady rhythm. Twenty hands moved, but only one pair belonged to the woman who truly commanded the room. Celestine Avery stood at the center of it all, shoulders squared, sleeves rolled, her face calm in that practiced way a storm can look calm from the sky. She was forty-ish, though hardship had made time hard to measure. Her hair was pinned tight. Her eyes were dark and watchful, as if they had learned to read the future by studying the smallest tremor in a candle flame.

“Miss Celestine,” whispered a young helper named Ruth, glancing toward the dining room door as though it might grow ears. “They say Mr. Hargrove’s friends are thirsty tonight.”

Celestine slid a tray toward her without looking up. “Then they’ll drink,” she said softly. “Men like that always do.”

Ruth hesitated. “You’re not… nervous?”

Celestine finally lifted her gaze. In it was something that didn’t belong to the kitchen: a depth that came from years of swallowing words whole. “I’ve been nervous for fifteen years,” she replied, and her voice was so even it could have been mistaken for peace. “Tonight I’m simply… finished waiting.”

Ruth didn’t understand. Not fully. She only felt the temperature of the room shift, as if the fire had inhaled.

The feast that promised to be memorable had been planned for weeks. The menu was extravagant by river-country standards: oysters on ice shipped from the Gulf, turtle soup rich with sherry, redfish baked with a thick shrimp sauce, roast pork with cornbread stuffing, chicken in a dark gravy that smelled like Sunday and sin, and desserts that would make even a disciplined man forget restraint. Celestine’s hands moved with a master’s certainty, each motion clean, each addition measured. People said she cooked like she was conducting music, and when they said it, they meant it as praise.

They didn’t know that she had learned to conduct other things too.

Fifteen years earlier, she had arrived at Oak Hollow as property.

Back then it was 1858, and the house didn’t shine with imported glass so much as it glared with certainty. Celestine had been twenty-three, purchased in New Orleans’ slave market by Silas Hargrove, a planter whose ambition was only matched by his impatience. He had wanted an exceptional cook. He had wanted a woman who could make guests forget they were eating in a humid corner of the world where mosquitoes wrote their names on skin. He saw Celestine’s straight posture, the steady way she met a buyer’s eyes without challenging him, and the neatness of her hands. He paid more than he intended and congratulated himself for it afterward like a man admiring his own reflection.

On the carriage ride upriver, Celestine stared at the river and did not cry. Tears, she had learned, were a kind of currency too, and she refused to spend them in front of anyone who wouldn’t pay the price they were worth. Her mother had once told her that the world was full of plants that healed and plants that harmed, and the difference between the two was often only the intention of the hands that harvested them. Her mother had been born in coastal marshland, where roots tangled like old stories, and she had taught Celestine remedies for fevers, poultices for wounds, teas for coughing babies. She had also taught her which leaves to keep away from mouths and which berries to never crush between fingers.

“Knowledge,” her mother had whispered one night while the wind rattled a cabin wall, “is a knife they can’t see until it’s already cut the rope.”

At Oak Hollow, Celestine worked like a woman walking a tightrope over fire. She learned the household’s rhythms, the way Silas Hargrove preferred his coffee, the way his wife, Marianne, flinched when his voice rose, the way the overseer’s boots sounded different when he was hunting someone. She became indispensable in the way a lock becomes dependent on its key. Because she was valuable, she was granted small mercies: a narrow room of her own behind the pantry, a better dress than field workers received, a handful of coins occasionally tossed her way when guests were pleased. Silas Hargrove liked to brag about her.

“That cook of mine,” he would say at parties, cigar between his teeth, “she’s worth ten hands in the cane.”

Celestine would keep her eyes down and let him believe that his approval was a sun she needed.

Then she had her son.

His name was Eli, and for seven years he was the closest thing Celestine had ever known to a life that felt like hers. He was bright-eyed and quick, his laughter sharp as cracked sugar. He slept curled against her side on nights when she could steal him into her narrow bed, and he followed her around the kitchen when she could smuggle him in, asking questions in a whisper so no one would hear his voice too boldly.

“Why do you put that in there?”

he asked once, watching her sprinkle herbs into a simmering pot.

“So it tastes like home,” she told him.

“But this isn’t home.”

Celestine paused, spoon hovering. She looked at him and tried to smile. “Home is a thing we carry,” she said. “Sometimes it’s a pot. Sometimes it’s a person.”

Eli grinned as if he understood. Children are generous that way, believing adults even when the world has given them every reason not to.

In the summer of 1858, a blight hit part of Hargrove’s cane. Rumors traveled faster than riverboats: that the price of sugar might dip, that a bank in New Orleans was tightening loans, that planters who’d borrowed too freely would have to make sacrifices. Silas Hargrove grew sharp-edged. He paced. He cursed at ledgers as though numbers were enemies he could threaten into obedience. One afternoon, traders arrived at Oak Hollow, men with paper smiles and eyes that assessed human bodies the way a butcher assessed meat. They spoke with Silas in the study while Celestine was kneading dough in the kitchen.

Then she heard her son scream.

It wasn’t a child’s normal cry. It was the sound of something being torn loose.

Celestine ran out, flour on her hands, heart battering her ribs. She saw Eli on the steps, wrists seized by a stranger, his face twisted with terror. Two other children stood nearby, trembling. A rope hung like a question in the air.

Celestine didn’t remember crossing the yard. One moment she was in the doorway, the next she was on her knees in front of Silas Hargrove, the dirt biting into her skin through her skirt.

“Colonel Hargrove,” she pleaded, because titles mattered to men like him more than lives ever did. “Please. Don’t do this. Don’t take my baby. I’ll work double. I’ll work till my bones turn to dust. Please.”

Silas looked down at her with the mild annoyance of a man interrupted mid-meal. “Get up, Celestine,” he said. “Business is business.”

“He’s seven,” she choked out. “He’s my son.”

Silas’s mouth tightened. “You’re young. You’ll have more.”

A hot dizziness swam through Celestine’s head. She reached for Eli, but the overseer shoved her back, and her shoulder struck the steps hard enough to spark pain down her arm. Eli cried out again, “Mama!” like the word might pull her to him the way gravity pulled river water.

Celestine grabbed at his shirt. For a breath, her fingers caught fabric, and she felt his small body tug toward her.

Then the trader yanked him away.

Eli was dragged to a wagon, his heels scraping grooves into the dirt. His eyes met Celestine’s one last time, and in them she saw something worse than fear: the moment a child realizes the world can decide you don’t belong to your own mother.

The wagon rolled off. Dust rose. The river’s humid air swallowed the sound of his voice as the distance grew.

That night, Celestine stood over a pot of stew and stirred with the same steady hand she had always used. No one in the big house noticed anything different. Silas even commented, satisfied, “You still cook fine.”

He didn’t understand what had broken in her.

It wasn’t her ability to work. It wasn’t her skill. It was the last soft thread of resignation, the last part of her that believed endurance was the same as survival. Something inside her turned hard and quiet. Hate entered her heart not like fire, but like iron cooling. And Celestine, who had lived her whole life learning when to stay still, decided she would not die without being heard.

But she was not foolish. Open rebellion meant a short rope and a shallow grave. The world around her was designed to crush visible defiance. So she hid her intention under obedience the way a blade hides under cloth.

And she began to study.

She had always known plants. Now she learned them as weapons without ever naming them out loud. She cultivated small things behind the kitchen where no one cared to look, mixing useful herbs with the harmless ones so the garden appeared ordinary. She listened to old women in the quarters, to whispers passed like contraband, to stories of what roots could do and what seeds could steal from a body. She watched how sickness moved through chickens, how a dog staggered after chewing the wrong leaf, how quickly a strong creature could become weak if the wrong thing entered its blood.

She never wrote anything down. Paper could be found. A mind, she trusted, could burn its secrets clean if needed.

Then the war came.

When cannons began to speak in the distance and men in gray marched past the river, Oak Hollow’s certainty wobbled. By 1862, Union troops held New Orleans, and the plantation world panicked like an animal sensing winter. Silas Hargrove swore the North would choke on its own righteousness. He hid silver. He hid documents. He hid his fear under anger, because that was the only disguise he knew.

Freedom arrived not as a clean door opening, but as a complicated storm.

By 1865, the law said Celestine was free. Her body belonged to herself, at least on paper. But paper did not stop hunger. Paper did not stop a planter’s friends from controlling a parish court. Paper did not return a stolen son.

Celestine stayed at Oak Hollow because staying gave her proximity. Staying gave her a chance to listen for news, to catch rumors from traveling hands, to follow any thread that might lead to Eli. She became a paid cook, technically, but wages in a place like St. Marais Parish were often another kind of leash. Silas Hargrove hated paying her. He hated that the world had shifted without asking his permission. He compensated by tightening his fists around what power he still had: contracts designed to trap freedpeople in debt, sheriffs who looked away when violence happened, laws that turned poverty into a crime.

Celestine watched all of it and waited.

Fifteen years is a long time to carry a scream in your chest. It changes the shape of you. It teaches patience that feels like cruelty.

So when Silas announced in November 1873 that he would host a grand banquet to celebrate the best sugar harvest in a decade, Celestine felt something inside her align, like a lock finally meeting the right key.

He made the announcement at breakfast with the smugness of a man trying to prove he was still king. “I’m inviting the best of them,” he said, buttering his biscuit hard enough to tear it. “Vandermere, Caldwell, Albright, Reardon, Tatum, all of them. They’ll remember who stands on this river.”

Marianne Hargrove’s hand trembled slightly around her cup. “It’s… a lot of expense.”

Silas shot her a look that could have curdled milk. “Expense is what men like us turn into profit,” he snapped, then softened his tone just enough to sound charming. “Celestine will make it worth every penny.”

Celestine kept her face neutral. “Yes, sir,” she said, and lowered her eyes like a woman who had never once imagined a different outcome.

Inside, she began to plan with the calm devotion of someone preparing a ritual.

The menu she designed was a masterpiece, and that was the point. A feast this fine would make men greedy. Greed made them careless. Carelessness created openings.

In the weeks before the banquet, Celestine worked harder than anyone expected, sending Ruth to fetch the freshest oysters, directing the boys to haul ice, ordering spices from a merchant in New Orleans. She smiled when Silas praised her. She accepted Marianne’s nervous gratitude. She played her role so well that even the servants whispered, “Miss Celestine’s proud of this one.”

Only at night, in the thin hours when the river fog crept close to the window like a curious ghost, did Celestine allow her true thoughts to breathe.

Eli would have been twenty-two now.

She didn’t know if he was alive. She didn’t know if he remembered her voice. She had followed rumors for years: a boy sold downriver, a boy sent to labor camps in the hills, a boy working in mines where the earth swallowed men without apology. Each rumor had turned to nothing in her hands. Justice was always a door that closed before she reached it.

So she built her own door.

On the night of December 14, the dining room filled with laughter and the clink of glass. The eleven planters gathered around Silas’s table like vultures dressed as gentlemen. Candles made their faces look softer than their lives deserved. They toasted the harvest, toasted the “return of order,” toasted the end of “Northern meddling.” Their wives smiled in practiced ways. Their sons watched and learned.

Celestine stayed mostly in the kitchen, but sound traveled. It slipped under doors. It rode on trays. It clung to the air like smoke.

“Reconstruction’s dying,” Colonel Vandermere boomed after his third drink. “You hear me? The politicians can pretend all they want, but the river don’t belong to Washington. It belongs to us.”

Colonel Albright chuckled. “And the labor belongs to us too, one way or another. Contracts. Debts. Vagrancy charges. A man’s got to keep the fields moving.”

Silas raised his glass. “To keeping the fields moving,” he said, and the men laughed like it was a clever joke.

Celestine carried a platter into the room and set it down with hands that did not shake. She felt their eyes slide over her as though she were part of the furniture, something useful and forgettable. She had spent a lifetime being underestimated. Tonight, she used their blindness like a cloak.

As course followed course, the men ate with appetite and arrogance. They praised the shrimp sauce. They praised the dark gravy. They praised the sweetness of the desserts as if Celestine’s hands existed only to serve their pleasure. She stood in the doorway once and listened as Silas told a story about “breaking” a man who tried to leave his contract early, and the table erupted in laughter.

Ruth, passing beside Celestine with a pitcher of wine, whispered, “They’re cruel.”

Celestine kept her eyes on the floor. “Cruelty,” she murmured back, “is what they call their normal.”

At 10:30, the party began to loosen into farewell. Men patted their bellies. Women dabbed at their lips with embroidered napkins. Some guests left by carriage, others by horse, traveling to plantations scattered across the parish and beyond, each one a small kingdom built on other people’s exhaustion.

One guest, Colonel Joseph Tatum, left earlier than the rest, claiming the road to his place was long and the night was thick with fog. He squeezed Silas’s shoulder and said, “Best meal you’ve ever put on, Hargrove. Your cook’s a miracle.”

Silas smirked. “Told you.”

Celestine watched them go and felt something settle in her chest, heavy and final.

After the last carriage wheels faded into the distance and the house began to quiet, she moved through the kitchen like someone erasing footprints. Pots were scrubbed. Counters wiped. Fires tended until they burned low. The usual mess of a banquet vanished under her careful hands, leaving behind only the faint scent of spice and smoke.

Near midnight, Celestine sat on the edge of her narrow bed and listened to the river.

She imagined roads stretching out from Oak Hollow like veins, carrying the guests back to their houses. She imagined them climbing into their beds, drunk and pleased, thinking of profits and politics, unaware that time had already begun to turn against them.

She didn’t sleep. She didn’t pray. She simply waited.

The first death came shortly after midnight.

At Colonel Vandermere’s plantation, his wife woke to the sound of him groaning as if he were wrestling something invisible. He clutched his belly and curled like a man trying to fold himself away from pain. Servants ran. Someone shouted for a doctor. By the time the lantern-lit wagon reached the nearest physician, Vandermere’s body had already gone strange and still, his face slack with shock.

Then Colonel Albright. Then Reardon. Then Caldwell.

A pattern spread through the parish like a whispered curse. Men who had eaten at Oak Hollow collapsed in their own bedrooms, their own studies, their own grand halls. Some lasted minutes, some longer. None of them made it to morning.

At Oak Hollow, Silas Hargrove woke around 1:00 a.m. with a sharp gasp, as though he had been punched in the gut by a ghost. Marianne bolted upright beside him.

“Silas?” she cried, reaching for him. “What is it?”

He tried to speak. His mouth opened, but the sound that came out was a broken animal noise, raw and terrified. He staggered toward the chamber pot, knocking over a chair. His skin went slick with sweat. His eyes bulged, not with rage now, but with something he had never allowed himself to show.

Fear.

Marianne screamed for help. Feet pounded in the hallway. A servant ran for Celestine, because Celestine was the one who always knew what to do. Celestine appeared in the doorway in her night dress, hair pinned, face composed as if she had been expecting this call for years.

“Get the doctor,” Marianne sobbed, gripping Celestine’s arm hard enough to hurt. “Please, Celestine, he’s… he’s—”

Celestine nodded once. “Yes, ma’am,” she said, and turned toward the door.

She walked to the stable at a pace that looked urgent to anyone watching, but the moment she was out of sight, her steps slowed. The night air was thick and warm, the kind that clung to lungs. Somewhere in the distance, frogs sang without caring about human tragedy. Celestine mounted a mule and rode toward the doctor’s house two miles away, not hurrying, not dawdling, letting time do what she had set it in motion to do.

When she returned with Dr. Henry Walsh, Silas Hargrove was already dead.

The doctor examined the body by candlelight, his brow furrowed, his fingers trembling slightly as he pressed and listened and searched for an explanation the world would accept. “It resembles… poisoning,” he murmured at last, voice low.

Marianne sobbed. “From what? We all ate the same meal!”

In the hours that followed, messengers arrived like birds carrying bad omens. One by one, they delivered news from other plantations: eleven of the guests, all of them men, all of them powerful, all of them present at Silas’s table, were dead. Only Colonel Joseph Tatum, who had left early and eaten less, survived, and even he lay sick for weeks, hovering in that feverish borderland where a man can see the shape of his own end.

By sunrise, St. Marais Parish felt as if it had been struck by lightning.

Authorities came from New Orleans, men in coats that looked too clean for river mud, asking questions with stiff voices and suspicious eyes. They searched the kitchen, the pantry, the cellar. They questioned servants, neighbors, anyone who had so much as walked past Oak Hollow that week. The doctor from the city spoke of “unknown toxins,” of “rare compounds,” of “possibilities,” but his words were fog. Toxicology was a young science, and in a parish where power often replaced proof, ignorance made a fine hiding place.

Celestine was questioned for hours.

A deputy leaned close to her, breath smelling of coffee and contempt. “You cooked the whole meal,” he said. “You handled every dish.”

“Yes, sir,” Celestine answered.

“And you tasted the food?”

“Yes, sir.”

“You didn’t see anything unusual?”

Celestine looked at him with tired eyes and let her voice stay plain. “I saw men eat,” she said. “I saw men drink. I saw men laugh.”

The deputy’s gaze sharpened. “Don’t get clever.”

Celestine lowered her eyes. “I don’t know how,” she said softly, and the lie sat in her mouth like a stone she had learned to carry.

Others were questioned too. Some were beaten. Some were threatened. But no confession came, because there was no group conspiracy to unravel. If there had been a dozen hands involved, a thread might have been pulled loose. Instead, there was only one mind, one quiet will, and fifteen years of patience.

After weeks, the investigation collapsed under its own frustration. Officials whispered about political sabotage, about rival planters, about “outside agitators.” They needed an explanation that didn’t require them to look too closely at the people they had spent their lives overlooking. In the end, the case was shelved under “unknown causes,” and St. Marais Parish returned to its anxious routines with a new ingredient: fear.

The men who remained powerful began to eat differently. They hired cooks from distant counties. They demanded tasting, demanded proof, demanded control. In their caution was an unspoken admission that the world under them could bite back.

Celestine remained at Oak Hollow for three more years.

Marianne Hargrove, now a widow, moved through the mansion like a ghost wearing pearls. Without Silas, the plantation’s finances unraveled. Debts that had been hidden surfaced like drowned bodies. The bank called in loans. The fields still produced, but the machinery of power had lost its operator, and even cruelty required management.

One afternoon in 1876, Marianne called Celestine into the parlor. The curtains were drawn against the sun, and the room smelled faintly of lavender and grief.

“I’m selling Oak Hollow,” Marianne said, voice thin. “I’m moving to the city.”

Celestine stood quietly, hands clasped.

Marianne swallowed. “You could leave,” she added, as if offering a gift. “You’re… you’re free, aren’t you? Legally.”

Celestine met her eyes. “Yes, ma’am.”

Marianne’s fingers twisted in her lap. “I have papers for you,” she said, and pushed an envelope forward. “A reference. Some money. It’s not much. But… you fed this house for years. You kept my children alive through the war. You—” Her voice cracked. “I don’t know what I’m supposed to say now that everything’s gone.”

Celestine took the envelope. It was heavier than it looked. “Thank you, ma’am,” she said, because thank you was a language she had been forced to learn even when gratitude was not what she felt.

Marianne’s eyes filled with tears. “Do you ever…” She hesitated, staring at Celestine as if seeing her for the first time. “Do you ever hate me?”

Celestine thought of Eli’s last terrified look. She thought of Silas’s laughter. She thought of fifteen years of swallowing rage until it became part of her blood.

Then she said, very quietly, “I think hate is a thing that eats the person holding it.”

Marianne flinched as if struck, and Celestine turned and left, her footsteps steady.

With the money Marianne gave her and what she had saved, Celestine went to New Orleans and opened a small food stall near the docks. Her cooking drew customers like a hymn draws believers. Workers came for bowls of gumbo thick with comfort. Children came for sweet bread. Women came and sat beside her, trading stories like coins.

But Celestine’s true purpose remained the same.

Eli.

She traveled when she could, following rumors upriver, then east, then north. She visited labor camps where men’s lungs were blackened by dust. She questioned old workers and freedpeople who had seen children taken, sold, leased, vanished. Some shook their heads. Some pointed her toward another road.

Years passed like that: cooking, saving, searching.

In 1881, she met an elderly man outside a church in a Tennessee mining town, a man whose back was bent but whose memory was sharp. He listened to her description of Eli, the year he was taken, the shape of his face, the scar on his chin from falling off a kitchen stool.

The old man’s eyes softened. “I remember a boy,” he said slowly. “Worked down in the earth. Called himself Eli. Said his mama could cook miracles.”

Celestine’s breath stopped. “Where is he?” she whispered.

The man looked away, and in that motion Celestine felt the world tilt.

“There was a collapse,” he said, voice rough. “In ’74. Took a few men. Took a couple boys too. They buried them quick. No names. Just dirt and prayer.”

Celestine stood very still, as if moving might shatter what remained of her.

The old man led her to a patch of ground behind the town where the earth lay uneven, as though it had never fully settled. There were no markers, only wild grass and the sound of wind moving through trees that didn’t care who rested beneath them. Celestine dropped to her knees and pressed her palms against the dirt.

For a long time, she didn’t cry. The tears came slowly, like water finally finding a crack in stone.

“My baby,” she whispered into the ground. “I looked for you in every river and road. I carried your name like a lantern. And all this time you were… here.”

She leaned her forehead to the earth. Her voice turned raw. “I did things,” she confessed, the words trembling out of her as if she had been holding them behind her teeth for decades. “I did terrible things. I thought it would make the world balance. I thought it would make the pain obey me.” She swallowed hard. “It didn’t bring you back. But I want you to know… your mama didn’t accept it quiet. Your mama didn’t kneel forever.”

The wind shifted. Grass moved. The world offered no answer, only its steady indifference.

When Celestine returned to New Orleans, she was changed, not into peace, but into something quieter: a grim kind of completion. She kept her stall, but she began to cook with a different purpose. She fed children who wandered the docks without parents. She gave meals to men who couldn’t pay. She taught young women how to stretch ingredients into sustenance, how to season poverty into something that didn’t taste like defeat.

One girl asked her once, “Miss Celestine, why you always feeding everybody?”

Celestine looked out at the river. The Mississippi glittered in the sun like a blade laid flat. “Because hunger makes people do desperate things,” she said softly. “And I’ve seen what desperation can grow into if you leave it alone.”

She never spoke of Oak Hollow. Not to the girls she taught, not to the men who praised her cooking, not even to the preacher who once offered her confession. The secret stayed in her body like an old scar, something that could ache in certain weather but would never be visible unless you knew where to look.

She lived until 1903, dying in a small house not far from where her stall had first stood. When she grew weak, neighbors came, people who owed her meals, advice, kindness they hadn’t been able to repay in coin. On her last night, as the room dimmed and the sounds of the city softened, Celestine stared at the ceiling and spoke as if someone waited there.

“I did what I thought I had to do,” she whispered, voice barely more than breath. “I won’t dress it up for heaven. I won’t pretend it was pure.” Her fingers curled weakly, as if grasping an invisible hand. “Let God judge me. Let my ancestors judge me. But let nobody ever say I didn’t love my child.”

She was buried in a crowded cemetery under a modest stone paid for by people who had once been hungry and then, because of her, had not been. At her funeral, women told stories about her generosity. Men spoke of her wisdom. Children, grown now, remembered the warmth of her stall on cold mornings, the way she always made room for one more bowl.

The story that mattered most remained unspoken.

Years later, fragments surfaced, as stories always do. A whispered rumor from an old servant. A parish record noting a string of deaths with no clear cause. A scholar’s curiosity. A pattern traced like constellations: eleven powerful men gone in one night, and a cook whose life afterward became an act of feeding rather than taking.

Celestine Avery was not a saint. She ended lives, and each death left grief behind, even if the grieving belonged to people who had never mourned the lives they crushed. Her hands carried both harm and healing, and that contradiction is what makes her difficult to hold in the mind. But her story forces a hard truth into the light: when a world denies justice to the powerless, the powerless sometimes build a justice of their own, imperfect and frightening and human.

And the river keeps flowing, carrying every secret downstream, pretending it never learned them at all.

THE END

News

THE PLANTER “GAVE” HIS HIDDEN DAUGHTER TO AN ENSLAVED MAN… AND NO ONE IMAGINED WHAT HE WOULD DO WITH HER

St. Jerome Plantation stretched across the Louisiana lowlands like a kingdom that didn’t need a crown to feel sovereign. In…

THE WIDOWED COLONEL WHO PAID THE HIGHEST PRICE AT AUCTION: THE FATE OF AN ENSLAVED WOMAN

No one who stood beneath the tin awning of the New Orleans sale yard on that damp March afternoon in…

ONE BALE OF COTTON, AND THE NAME THEY TRIED TO BURN

March 3rd, 1838, Charleston, South Carolina, arrived with a cold rain that turned the cobblestones into dark mirrors. Elias Hart…

THE “FAT SLAVE” WAS FORCED TO EAT OFF THE DIRT LIKE AN ANIMAL — BUT THE PLANTATION LADY PANICKED WHEN SHE SAW WHO WAS WATCHING

The afternoon heat didn’t just press down on Magnolia Ridge Plantation, it seemed to knead the whole Louisiana sky into…

THE WIDOWER WHO BOUGHT A FAMILY AT AUCTION AND TURNED THE WEST INSIDE OUT

The summer of 1882 came down on the Wyoming Territory like a judgment that refused to blink. Heat sat on…

Single Dad Blocked at His Own Mansion Gate — Minutes Later, He Fires the Entire Security Team

The truck coughed like it had something to confess. Caleb Reed kept both hands on the steering wheel anyway, as…

End of content

No more pages to load