The little frontier town of Redwillow, tucked into the wide belly of the Montana Territory, looked almost pretty from a distance. Lanterns bobbed on posts like captured fireflies, and the first honest breath of spring carried thawed earth, fresh hay, and the sharp sweetness of roasting meat. But the closer you stepped to the square, the more you heard the truth underneath the fiddle music: coins clicking, boots grinding in mud, and men practicing the kind of laughter that wasn’t joy so much as permission. Wagons circled the stalls where saddles hung like trophies and cattle brands were stamped into leather, yet the loudest calls weren’t for goods. They were for bargains. For bodies. For anything a desperate man could turn into a receipt.

Hannah Mayfield stood at the edge of that sound as if the noise might decide to spare her if she didn’t move. She was twenty-three, slender in a way that came from too many winters of working and too little meat on the table, with chestnut hair pinned under a faded bonnet that had seen better hands. Her boots were caked with fresh mud, and the cold dusk made her breath visible, each exhale a small confession she couldn’t stop making. Shame sat on her brow like a thumbprint left by someone who’d handled her life without asking, and it burned worse because she couldn’t name the single moment it started. Maybe it began the day she learned her first husband wanted an heir the way a man wanted rain, like the world owed it to him. Maybe it began the day a midwife’s mouth tightened and her eyes slid away, as if honesty was a cruel tool best used quickly.

Behind Hannah, Silas Mayfield cleared his throat and straightened his shoulders, trying to stand like a man who still belonged to himself. Once, he’d been a horse trader with pride and a good name. Debt had chewed those things into scraps. Now he held Hannah’s future like a promissory note, and he raised his voice so the whole square could hear. “Folks,” he called, forcing cheer into the word. “Here’s a young woman steady with a broom, clever with a needle, and she can keep a house running when the wind’s trying to blow it clean off the earth.” He swallowed, and the next sentence came out like a stone. “She can’t bear children.”

The square shifted. You could feel the attention turn as surely as sunflowers follow light. Men in dust-streaked hats glanced over like they were assessing a mare’s teeth. Women pulled their children closer, as if barrenness were contagious, as if the absence of a baby could jump from one womb to another on a gust of air. Hannah’s cheeks flared hot, not from embarrassment alone, but from the familiar sting of being reduced to one failed function. She’d tried the bitter drafts. She’d knelt for prayers until her knees bruised. She’d stared at the ceiling on nights when her husband lay beside her stiff with disappointment, and she’d begged her own body like it was a stubborn gate refusing to swing open. None of it mattered now. In this square, she was being introduced like a broken tool with a polished handle.

Silas continued, desperate as a man tossing his last coin into a river. “Half the price of a steer,” he said, and Hannah felt that sentence hit her ribs. “No grand promises, but you’ll get a woman who knows work. Anyone willing to take her tonight?” The word take landed wrong. It made Hannah’s stomach fold in on itself, and she stared at the ground because looking up would mean meeting eyes that had already decided she was less than a whole person. The murmur grew sharper, like a blade being tested on a thumb. Someone coughed. Someone laughed. Someone said, “Ain’t that convenient,” as if her life were a trick designed to cheat an honest man.

Then a hand thumped something heavy onto the rough plank table, and the crowd startled as if a bell had rung. A canvas sack of coins sat there, worn and dusted, like it had traveled a long way in a coat pocket. The man who placed it didn’t posture, didn’t grin, didn’t bargain for sport. He simply stood, broad-shouldered and steady as a barn beam, with grief carved into his weather-browned face so deeply it looked permanent. Caleb Rourke, they called him. Thirty-five, widowed. A rancher from the outskirts who’d lost his wife and small son to fever years ago and had built his solitude like a fence no one climbed unless invited.

Caleb’s gaze moved from Silas to Hannah, not lingering on her body like the others did, but settling on her eyes as if he expected to find a person there. He stepped closer, and the clink of his coins felt louder than the town’s gossip. Leaning slightly, he spoke only to her, low enough that she could have pretended she hadn’t heard if she wanted to keep the old habit of disappearing. “I don’t need children,” he said. “I need someone who knows how to stay.”

Silas blinked, a flicker of relief and greed fighting in his face, and he nodded too quickly, as if afraid the offer might vanish. There was no ring. No preacher. No booming announcement. Just a transaction done in plain daylight, which somehow made it uglier and cleaner at the same time. Hannah’s heart pounded so hard she felt it in her throat. She didn’t know if she’d just been rescued or re-packaged. But Caleb didn’t touch her. He didn’t claim her with a hand on the arm, the way men did when they wanted witnesses to see ownership. He simply tipped his chin toward the wagons and said, almost gently, “If you’re willing.”

Hannah took one step. Then another. Not because the choice felt good, but because standing still in that square felt like slowly drowning. She climbed into the wagon beside Caleb, her hands folded tight in her lap, as Redwillow’s lanterns shrank behind them. The road out of town was rutted, and the wagon rocked, but Caleb drove as if he understood that every jolt could shake loose something fragile inside her. Hannah watched his profile in the dim light, trying to read him the way she’d learned to read weather. He looked like a man who’d been rained on enough times to stop cursing clouds. Not a savior. Not a villain. Just someone offering a roof without the usual bargain of pretending she was more convenient than she was.

Juniper Creek Ranch didn’t greet them with warmth. It greeted them with wind. The land spread wide and honest, grass still waking from winter, and the house stood tall but tired, timber weathered the color of old bones. The windows were dark, not from neglect, but from a kind of quiet that lived there by habit. When Caleb stopped the wagon, he climbed down first and offered Hannah a hand, his grip firm but not demanding. She hesitated long enough to remember every time a hand had been offered as a trap, then took his anyway. Stepping onto the porch, she noticed a rocking chair swaying in the breeze like it couldn’t forget the motion of a body that used to sit there.

The door opened before Caleb could knock. A gray-haired woman appeared, shawl wrapped tight, eyes sharp with suspicion that had been sharpened by too many losses. Agnes Rourke, Caleb’s mother. She looked Hannah up and down the way a person examined a new fence post, deciding how long before it rotted. “This her?” Agnes asked, voice like dry kindling. Caleb didn’t flinch. “This is Hannah,” he said. “She’ll be living here.” Agnes’s mouth tightened. “Living,” she repeated, as if the word itself was an insult to the dead. “For what purpose?” Caleb’s answer was simple. “To help. That’s all.” Agnes turned away without offering welcome, her silence louder than refusal.

Inside, the house was clean but joyless, as if someone had scrubbed everything that dared to feel. No portraits lined the walls. No toys lay in corners. The air smelled of soap, wood, and something missing. Caleb led Hannah to a small room at the end of the hall. “This used to be for guests,” he said, setting down her bundle. “Sheets are clean. You’ll find what you need.” He paused at the doorway, as if he was weighing whether kindness would make things worse. Then he left and returned with a folded wool coat, soft and heavy, stitched with fading flowers. “My wife wore this,” he said quietly, placing it on the bed like an offering he wasn’t sure she deserved to make. “Figured it might help when the cold comes back.” Hannah’s fingers traced the seams, and something in her chest pinched, not jealousy but the strange ache of being given proof that she wasn’t expected to erase a ghost.

Before he left, Caleb said the words she hadn’t known she needed. “You’re not here to replace anyone. And I won’t ask you to.” That night, Hannah sat on the edge of the bed and listened to the house settle, floorboards creaking like old knees. She didn’t unpack. She didn’t cry. She didn’t know which would be worse: weeping in a room that didn’t belong to her, or keeping her tears locked up until they turned into stones. When she finally lay down, she found a hot brick wrapped in cloth tucked under the bedcovers near her feet, still warm. No one mentioned it. No one claimed it. But the heat seeped into her bones like a small, anonymous promise: someone noticed you might be cold.

Days turned into weeks the way they did on the frontier, not with ceremonies, but with repetition. Hannah swept, mended, fed chickens, scrubbed the stove until the iron shone. She moved quietly at first, as if making noise would remind the house it had been invaded. Caleb spoke little at breakfast, not because he was rude, but because silence had become his native language. Agnes watched Hannah the way a fox watched a gate: always looking for the weak spot. One morning, after Hannah set down biscuits and poured coffee, Agnes finally cut into the quiet. “You don’t smile much,” she said, not as comfort, but as accusation. Hannah looked up slowly. “I wasn’t brought here to smile,” she answered, and her voice surprised her with its steadiness.

Agnes’s eyes narrowed. “No,” she muttered. “You were brought here because no one else would have you. A woman returned once is a woman marked.” The words slipped under Hannah’s skin like splinters. She felt her hands still over the skillet, and she forced herself not to react, because reacting would be admitting Agnes had the right to define her. Hannah finished cooking, set the plate down, and left the room without a word. She walked out behind the house where the fence line met a cottonwood tree, and there, as if the land itself carried memories, a child’s swing still hung from a branch. Weathered rope. A plank seat. Hannah sat, gripping the wood, staring at the empty yard, and wondered what it felt like to be so wanted that your absence became a hole in a whole place.

Caleb found her there later with a pail of feed, the kind of excuse men used when they wanted to offer closeness without asking for it. “Chickens need you tomorrow,” he said simply. “I’ve got to ride out to the north pasture.” Hannah nodded, her throat tight. He hesitated, then added in a quieter voice, “My mother thinks in bloodlines. She thinks I’m living as a placeholder for what I lost.” Hannah stared ahead. “And you?” she asked, barely louder than the wind. Caleb’s answer was like the weight of a hand on a shaking shoulder, firm without being possessive. “I don’t,” he said. Then he walked away, leaving her with a strange new kind of ache: the ache of being trusted when you no longer trust yourself.

By midsummer, the fields had dried to gold, and the days grew long enough to hold a little hope if you let them. Hannah’s hands remembered how to work without trembling, and her shoulders stopped hunched. It happened slowly, the way healing often does, so gradual you don’t notice until you look back and realize you’re standing differently. One morning, two children from a neighboring homestead wandered up the path, dirt on their cheeks and curiosity in their eyes. They’d heard Hannah read aloud to herself while hanging laundry, her voice carrying words like small lanterns. Hannah didn’t have much, but she had letters. She had stories. She had a patience that came from surviving disappointment.

She cleared a corner of the barn loft where dust caught sunlight and made it look holy. There were no desks, just crates and burlap cushions, but the children came anyway, as if learning their names on paper might make them safer in a world that often forgot them. Hannah taught them to trace letters in ash, to count kernels of corn, to read simple lines from a tattered book that smelled of smoke and years. Word spread the way it always did, first quietly, then with a kind of hunger. Soon, more children arrived, some barefoot, some shy, some so hungry their focus trembled. Caleb never commented. But Hannah began noticing wagon tracks in the dirt that weren’t hers, looping wider than necessary, touching the edge of farms where kids had been kept home like livestock. Someone, quietly, was sending them.

The first time Hannah burned the biscuits, she thought the spell would break. She’d gotten caught up in teaching and forgotten the oven. Smoke poured out, flames licking the edge of the pan like punishment. She rushed to douse it, eyes stinging, heart pounding, already building a list of apologies she expected to deliver. That evening, she set the blackened tray outside like evidence of her failure, braced for the scolding she’d known all her life. Caleb passed by on his way from the stables, stopped, looked at the char, then at her face. For a moment Hannah saw his grief flicker, not aimed at her, but at the idea of anyone being judged by a ruined pan. “Any biscuit left standing still,” he said softly, “is better than a person who got burned trying.” He walked on as if the words were nothing. But Hannah stood there with smoke curling around her and felt, for the first time, that being imperfect didn’t mean being disposable.

Agnes didn’t soften quickly. Grief rarely does. One night she found Hannah scrubbing the stone sink, sleeves wet, hair loose from the heat. “This house used to have a child’s voice in every room,” Agnes said, leaning on her cane. “Now it’s full of silence and strangers.” Hannah’s hands stilled, and she couldn’t tell if Agnes was accusing her or mourning out loud. Instead of arguing, Hannah dried her hands and walked out into the night. She climbed the slope behind the house where the wind cut clean and the stars felt close enough to touch. She stood there until the moon rose, her heart aching not from Agnes’s cruelty, but from the truth inside it. This place had lost something irreplaceable. No wonder it resisted replacement.

Caleb’s footsteps came steady behind her, crunching on dry earth. He didn’t call her name, didn’t try to fix her sadness with speech. He simply stood beside her under the wide sky and reached into his coat. “Found this,” he said, holding out an ivory-handled comb worn smooth. “My wife used to sit right here, brushing her hair before bed.” Hannah took it carefully, as if it might shatter. Caleb’s voice stayed low. “No one’s asking you to be her,” he said. “Not me. Not even my mother, no matter how sharp her mouth gets. Just be Hannah.” The words slid into a place inside her that had been empty a long time, and she nodded once, comb pressed to her chest like a quiet vow: I will try to exist as myself.

When autumn came, so did the town’s hunger for explanations. Folks could tolerate kindness only if it fit a familiar shape, and Hannah didn’t. In Redwillow’s store, between sacks of flour and barrels of nails, whispers gathered like dust. “Rourke took in a barren woman,” they said, as if her womb were the only room in her body. “Returned to her father once,” someone snorted. “Probably takes up in his barn like a stray.” Hannah tried not to listen, but gossip has a way of sliding under doors. At first she told herself it didn’t matter. She had work. She had the children. Then the children started to disappear.

It wasn’t sudden. It was worse: it was polite. A mother would wave less. A father would mutter excuses about chores. A week later, no boots clattered up the path. The barn loft sat empty, dust settling in the places laughter used to live. Hannah stood on the porch each morning with chalk in her apron pocket, waiting for small faces that never arrived, then turned back inside with her spine stiff as pride. Caleb noticed. He didn’t ask questions that would make her relive the humiliation. He simply started fixing up an old shed behind the barn, patching holes, laying down boards, making a warmer place for learning as if faith itself could be built with nails.

One cold afternoon, Hannah took a narrow trail by the mill to save time on the way back from town. Her arms were full, salt and fabric pressed against her ribs, and the sky looked bruised with coming weather. Near the bridge, a man waited with a bottle in hand, coat stained, beard untrimmed, eyes bright with the mean courage whiskey lends. “Well, look at that,” he slurred. “The one they tossed out.” Hannah’s steps slowed, then stopped. The man swayed closer. “Rourke pick you up like a mutt,” he sneered. “You warming his bed or just his barns?” Hannah’s throat tightened, but she forced her voice steady. “Move,” she said. The man laughed and took another step, and the sound of his boots on the boards felt like a threat with hands.

Hoofbeats thundered on the trail, sudden and hard. Caleb appeared like a shadow made solid, swinging down from his horse. He didn’t shout. He didn’t posture. He simply stepped between Hannah and the drunk and looked at the man with an expression so calm it was terrifying. Caleb’s silence was a blade. The drunk’s grin faltered. Caleb didn’t even address him at first. He checked Hannah’s hands, her face, as if verifying she was still herself. Then he held out the reins. “Come on,” he said to Hannah. She climbed up without speaking, and Caleb mounted behind her, his presence a wall at her back. They rode home with the wind cold and sharp, and Caleb finally said, not as consolation but as truth, “People talk about what they don’t understand. Fear makes a sport out of other folks’ pain.” Hannah stared ahead. Caleb’s voice softened. “But you,” he added, “you understand what I need. And that’s more than any of them ever bothered to learn.”

Rain came after that, relentless and heavy, turning the earth into a soft, sucking mess that swallowed footprints and made every trip feel like resistance. Hannah worked in the storage shed, clearing warped crates and forgotten barrels, imagining benches and shelves and a stove that could keep children warm through winter. One afternoon, beneath an old tarp, she found a wooden chest dark with age, its brass latch rusted shut. The hinges groaned when she pried it open, releasing the scent of cedar and dried thyme like a memory exhaling. Inside lay brittle papers, yellowed linens, and a thick leatherbound book stamped with one word: ROURKE.

Hannah flipped through the family ledger slowly, fingers careful, as if names were fragile things. Births. Deaths. Marriages. Stillborn infants marked with small crosses. Near the back, she found Caleb’s entry, and beside it his wife’s: Evelyn Rourke, married 1879. One child, Samuel, born and buried in the same winter. Beneath that, a final line waiting like a breath held too long, and the words had been crossed out again and again, as if someone tried to erase even the possibility of hope. Hannah’s eyes burned. She didn’t want to intrude on grief written in ink. Yet she felt the strange pull of that blank space, the temptation to write her own name and prove she belonged. Her hand hovered over the page, then she closed the book gently. Not yet, she told herself. Belonging shouldn’t be stolen. It should be offered.

That night, Caleb came in soaked from the field, rain dripping from his hat brim. By midnight he was shivering, fever taking him like a tide. Agnes muttered prayers through clenched teeth, but her hands shook too much to be useful. Hannah sat beside Caleb, wringing cloths, changing water, keeping her voice low and steady even when fear tried to climb her throat. She didn’t dramatize the care. She simply stayed, because staying was the only promise she knew how to keep. Before dawn, she placed the family ledger on the table near his bed, open to that crossed-out page, and set a pen beside it. She didn’t write her name. She waited, letting Caleb decide what the book could hold now.

When Caleb finally stirred, pale and blinking at the soft gray light, his eyes landed on the ledger. He reached for it slowly, thumb brushing the worn leather as if greeting an old wound. He read the page, his jaw tightening, then easing. He picked up the pen. Hannah held her breath, not from expectation, but from respect. Caleb wrote in firm, careful strokes: HANNAH MAYFIELD, NOT BORN OF BLOOD, BUT CHOSEN STILL. He set the pen down like a completed prayer. When Hannah’s eyes filled, she turned her face away, embarrassed by her own tenderness. Caleb’s voice rasped, half amused, half sincere. “If the world insists on naming you by what you lack,” he murmured, “then I’ll name you by what you do.”

A week later, the mail rider brought an envelope stamped with an official seal, and the paper inside carried the cold language of property records. Verification required. Legal names of proprietors. If married, indicate legal spouse. Hannah read it at the table with hands that suddenly felt too small for the weight of it. She and Caleb had never stood before a preacher. No rings, no vows, no public claiming. Their bond lived in chores shared, in silence that didn’t wound, in the way Caleb’s hand paused near her shoulder without demanding. But the letter reminded her that the world only respected what it could file.

That evening, Caleb placed the paper between them like a quiet challenge. “I don’t need anyone’s name on that land to know it’s ours,” he said. “But if you want yours there, take the pen. No courthouse needed. No preacher.” Hannah stared at the blank line, at the space where she could become official in a world that had tried to sell her cheap. Her hand trembled. Then she didn’t write “spouse.” She wrote CO-OWNER, and under it: HANNAH, BY CHOICE, NOT BY BLOOD. She slid the paper back. Caleb didn’t smile broadly, didn’t make a speech. He simply folded it with care, the way a man handled something precious, and tucked it away like a promise he planned to keep.

The next day, Hannah noticed the document framed on the kitchen wall between the calendar and the window, pressed neat so the ink didn’t smudge again. It wasn’t a marriage certificate. It was something quieter and, to Hannah’s astonishment, stronger: proof that she hadn’t been “taken.” She’d been included. When Caleb caught her looking, he said softly, “Most folks frame wedding pictures.” His eyes held hers. “I’d rather frame the thing that gave us choice.”

Autumn had nearly surrendered to winter when a black carriage rolled up to Juniper Creek’s gate, polished too fine for dirt roads, as if it believed it could stay clean by refusing reality. A man stepped out in a tailored coat that had never known dust, hat brim trimmed, boots shining like vanity. Hannah froze on the porch with a bowl of peas in her lap, her fingers suddenly numb. She knew that posture. That entitlement dressed in regret. Richard Hale, her former husband, stood at the foot of the steps with a face older than it should’ve been, and hope flickering like a match he didn’t deserve to light.

“Hannah,” he said, voice low, trying to make the name sound like a doorway back to the past. He held out a velvet pouch. “A token. For old times.” Hannah didn’t take it. She watched his hand hover there, as if he expected her to be trained by habit. “You’re too late,” she said quietly. Richard’s smile faltered. “I came to say I was wrong,” he rushed. “My wife… she died last spring. And the doctor says I’ll never have children of my own.” He swallowed, searching Hannah’s face for pity, for softness he could use as leverage. “I understand now. Blood isn’t what makes a home. Come back. Be my wife. We can start again.”

Behind the screen door, Caleb stood silent, not looming, not intervening, simply present like truth. Hannah felt the air shift, as if the porch balanced on the line between old humiliation and new peace. She looked at Richard, and her voice didn’t shake. “You know what’s strange?” she said. “I used to wait for someone to say those words.” Richard leaned in, hope brightening. “Then say yes,” he whispered. Hannah exhaled, slow and steady. “But the man who said them,” she continued, “came too late. And the man who never needed them… is the one who gave me a place to belong.”

The velvet pouch slipped from Richard’s fingers to the boards with a dull thud, like a failed offering. The screen door creaked, and Caleb stepped out. He didn’t insult Richard. He didn’t raise his voice. He simply placed a gentle hand on Hannah’s shoulder, and the contact made her spine straighten with certainty. Caleb’s gaze met Richard’s, calm as winter. “She was never something returned,” Caleb said quietly. “So you don’t get to ask for her back.” For a long moment, the only sound was wind through dry grass. Richard’s shoulders sagged. He nodded once, not forgiven, but dismissed by reality. He turned, climbed into his carriage, and rolled away, the polished wheels leaving the same muddy ruts as any other man’s.

Winter came early, piling snow on rooftops and draping the prairie in quiet. And yet, against that cold, something stubborn grew. The shed Caleb had patched became a real schoolroom with benches and shelves, a small stove that glowed like captured sunlight. Children returned, first timidly, then with the certainty of hunger finally offered food. Not every parent approved, but enough did, and enough children arrived that Hannah’s voice filled the room again. Some called her “Miss Hannah.” Some, with the blunt logic only children had, called her “Mama Hannah,” because she fed them stories and safety and never asked what they could give in return.

As the season turned, Hannah began to feel tired in a way she couldn’t explain. Chalk dust made her cough. Her hands trembled sometimes, and she blamed the cold, then the work, then the years of being tense. One spring market day, beneath a pale sky, Hannah’s vision narrowed in the street as if the world were closing its fist. She collapsed among crates and voices. Caleb, unloading supplies at the edge of town, saw the commotion and ran like fear had finally found a crack in his fences. He carried her home in his arms, his jaw clenched so hard it looked like it might break.

The doctor arrived late, breath steaming, fingers cold. Agnes hovered in the doorway, rigid as a sentry, her face pale. Hannah lay on the bed, cheeks hollowed by exhaustion, and when the doctor finished his examination, his expression shifted with surprise that softened into something like wonder. “She’s expecting,” he said. “About eleven weeks.” Silence struck the room. Hannah stared at the ceiling, tears slipping sideways into her hair. “I was told I could never,” she whispered, voice raw. The doctor shrugged gently, as if the body was a landscape full of hidden springs. “Then you were told wrong,” he said. “Or perhaps… you were told by someone who needed certainty more than truth.”

Caleb didn’t explode with joy. He didn’t make the moment about triumph, because he knew this wasn’t a prize to prove the world wrong. His eyes were wet, but his voice stayed steady. “Whatever happens,” he said, taking Hannah’s hand, “you don’t have to earn your place here with a child.” Hannah squeezed his fingers, and in that grip she felt the real miracle: not pregnancy, but safety. Agnes turned away, wiping her face with the edge of her shawl as if she could hide emotion the way she’d hidden grief for years.

The months that followed were fragile and bright. Caleb planted three pear saplings outside the porch, calling them the Hope Orchard with a faint, shy humor that made Hannah smile. Children taped drawings to the schoolroom wall: tiny hearts, babies wrapped in quilts, flowers blooming under snow. Agnes, without announcing it, began leaving extra soup on the stove, began checking Hannah’s blankets at night, began sitting in the schoolroom doorway sometimes, watching children read with an expression that looked almost like peace. One evening she said, quietly, “I hated the idea of anyone living where my Evelyn lived.” Hannah’s throat tightened. Agnes’s eyes shone, hard and honest. “But I hate more the idea of a house dying just to honor the dead.” It wasn’t an apology, not exactly, but it was a bridge, and Hannah stepped onto it.

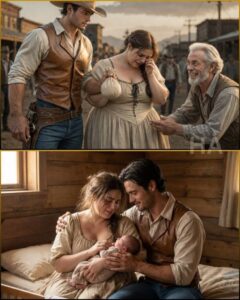

The storm that brought the baby arrived like a furious visitor. Wind slammed the shutters. Rain lashed the windows. Thunder cracked the horizon as if the sky itself were splitting. The doctor was delayed by flooded roads, and panic tried to rise like bile. Hannah clutched Caleb’s hand until her knuckles whitened. Caleb’s voice stayed low and anchored. “You’re not alone,” he told her, as if speaking could build a shelter inside her. Agnes boiled water, hands steady now, not because fear had vanished, but because love had finally outranked it. When the baby’s cry cut through the storm, it sounded like sunlight punching through ice.

A girl. Dark-eyed. Loud-lunged. Alive with the insistence of new beginnings. Hannah sobbed with a joy that felt almost frightening, not because she hadn’t wanted this, but because she’d stopped letting herself believe she could. Caleb held them both with arms that trembled, his face raw with tenderness. “She looks like you,” he whispered, voice thick. “Brave enough to come where we were afraid to stay.” Outside, the rain eased, and the wind softened as if listening.

When the house finally quieted, Caleb brought the family ledger to the bedside, its leather warm from his hands. He opened to the page where he’d written Hannah’s name months ago, and this time he wrote again beneath it, slow and careful: CLARA ROURKE, DAUGHTER OF TWO SOULS WHO BUILT A HOME FROM CHOICE. Hannah watched the ink dry, and she understood something she hadn’t fully understood even in her happiest moments: the real harvest wasn’t the baby. It was the life they’d built when no one was watching, when no one was applauding, when love was just a daily decision.

Spring returned with pear blossoms drifting on the breeze like soft snow, and the schoolhouse kept its name, carved above the door by Caleb’s steady hands: HANNAH’S SCHOOL: FOR HEARTS, NOT HEIRS. Children still ran up the path every morning, boots thudding, laughter rising. Some were orphans. Some were simply lonely. All were welcomed. Clara grew in a house where silence didn’t mean punishment, where grief was allowed to sit at the table without swallowing the meal, and where a woman once labeled “barren” learned that bodies weren’t the only thing that could bear life. A heart could, too. A home could. A name, spoken gently and kept with care, could grow into something that outlasted storms.

And if anyone in Redwillow still whispered, their whispers no longer ruled the air. The ranch stood with windows lit, orchard blooming, and the schoolroom warm even on bitter mornings. Not every love story needed a wedding. Some needed something rarer: a hand that didn’t let go, a choice that didn’t require proof, and a place where “stay” finally meant “belong.”

THE END

News

All Doctors Gave Up… Billionaire Declared DEAD—Until Poor Maid’s Toddler Slept On Him Overnight

The private wing of St. Gabriel Medical Center had its own kind of silence, the expensive kind, padded and perfumed…

Mafia Boss Arrived Home Unannounced And Saw The Maid With His Triplets — What He Saw Froze Him

Vincent Moretti didn’t announce his return because men like him never did. In his world, surprises kept you breathing. Schedules…

Poor Waitress Shielded An Old Man From Gunmen – Next Day, Mafia Boss Sends 4 Guards To Her Cafe

The gun hovered so close to her chest that she could see the tiny scratch on the barrel, the place…

Her Therapist Calls The Mafia Boss — She Didn’t Trip Someone Smashed Her Ankle

Clara Wynn pressed her palm to the corridor’s paneled wall, not because she needed the support, but because she needed…

Unaware Her Father Was A Secret Trillionaire Who Bought His Company, Husband Signs Divorce Papers On

The divorce papers landed on the blanket like an insult dressed in linen. Not tossed, not dropped, not even hurried,…

She Got in the Wrong Car on Christmas Eve, Mafia Boss Locked the Doors and said ‘You’re Not Leaving”

Emma Hart got into the wrong car at 11:47 p.m. on Christmas Eve with a dead phone, a discount dress,…

End of content

No more pages to load