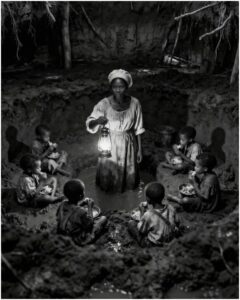

THE MOTHER WHO HID EIGHT CHILDREN UNDER THE EARTH

At the beginning, the story sounds like a rumor that refuses to die, the kind people repeat with lowered voices as if the walls might report them. They say a woman once built a world beneath the soil, not for treasure, not for escape, but for children. They say those children learned the shape of life by touch and breath, learned time by footsteps above them, learned love by the quiet scrape of their mother crawling down a narrow tunnel night after night. If you are hearing this now, imagine where you are, and what hour your clock insists it is, because stories like this travel farther than the people who tried to bury them.

It was 1820 in Michoacán, when the valleys looked generous from a distance and brutal up close. The volcanoes stood like old judges around the horizon, and the lakes reflected the sky with such calm that a stranger might believe peace lived here. Yet the haciendas were kingdoms sealed off from mercy, and inside those fenced worlds the laws were written by men with keys. La Purísima was one of the largest, sprawling across thousands of hectares of maize and wheat, with cattle pens that smelled of warm breath and sour straw, and barracks where human beings slept packed together like tools put away after use.

The owner, Don Hernando Villareal Yuña, had reached the age where most men soften, but he had spent his life sharpening himself instead. He was rich in the way that made him feel righteous, as if the size of his land proved the size of his soul. He spoke of slaves the way merchants spoke of mules, as units that could be traded, sold, exchanged, corrected with pain if they misbehaved. He believed families made people weak, and weakness made people disobedient, and disobedience cost money. So he maintained a rule with the cold devotion other men reserved for prayer: no child born to an enslaved woman would remain at La Purísima. Babies were sold before they could learn their mother’s face, before their mothers could stop hearing the small sounds of them breathing. If a woman cried too loudly, she learned how a whip could turn grief into silence. If she tried to hide her child, she learned what “example” meant, because the hacienda was always ready to teach the others.

In twenty years, more than forty infants disappeared from La Purísima as if the earth itself had swallowed them, and the world above continued eating, laughing, bargaining over corn. The mothers did not forget, but forgetting was not required for the machine to run. It only required that their bodies keep moving, hands keep picking, backs keep bending, mouths keep obeying. The system was built on a simple trick: it convinced people they had no choices, and then punished them for imagining one.

Petra was nineteen in 1820, small enough that overseers called her “bird” when they wanted to be amusing, thin enough that she could slip between workers without being noticed, and quiet enough that even cruelty sometimes passed her by because it could not find her. She had been born at La Purísima, the daughter of a woman who died when Petra was six, leaving behind not a family, not a name anyone cared to preserve, only a gap that never stopped aching. Petra did not remember her father. She did not remember siblings. She remembered loneliness like a taste that never left her mouth, and she remembered watching other women have their babies taken away, the way their faces changed afterward into something hollow and obedient that scared Petra more than the whips did.

From childhood, Petra learned the skill that kept her alive: she observed. She listened longer than she spoke. She noticed which guards drank too much and stumbled at night, which overseers were lazy and liked shortcuts, which routes were least traveled, which corners of the property were ignored because they produced no profit. Patience became her secret weapon, and inside that patience grew a vow she never said aloud, because speaking vows in places like La Purísima was dangerous. She promised herself that if she ever had a child, she would not hand that child to the darkness of the market.

When Petra realized she was pregnant, she did not collapse into pleading. She did not cry in public, because public tears were invitations. She went still inside, like water turning to ice, and then she found Simón.

Simón worked at the stables, a man with broad shoulders and gentle hands who spoke to horses the way he wished people spoke to each other. He had been kind to Petra in the small ways that meant everything, saving her a piece of bread when he could, standing between her and an angry overseer once, pretending he had a question just to pull attention away from her. Their love was not the kind that belonged to songs. It belonged to stolen minutes, quick glances, hands brushing in the dark, hope folded into secrecy. When Petra told him she was with child, Simón’s first instinct was the most human one: he wanted to ask for mercy.

“I can work more,” he whispered. “I can take night shifts. I can promise the child will be obedient. Maybe…”

Petra shook her head. Her eyes, usually lowered, locked onto his like a warning. “If they know,” she said, “they will watch me. They will wait for the birth. They will take the baby and call it order.”

Simón’s mouth tightened. “Then what do we do?”

Petra looked past him, toward the fields, toward the fences, toward the soil that held roots and bones and secrets. “We hide the child,” she said.

“Where?” Simón asked, and the question carried the weight of despair, because the hacienda seemed to own every inch of air.

Petra’s lips did something rare. They curved, not into joy, but into the shape of determination. “They know what is above ground,” she said. “They do not know what is under it.”

What Petra proposed was madness, and yet madness was sometimes the only doorway out of a nightmare designed by sane men. Behind the slave barracks, beyond a patch of scrub and thorn that no one bothered to clear because it produced nothing, the ground softened. The earth there was fertile and easy to move, the kind of soil farmers praised, not realizing it could also hide a revolution.

Night after night, when the hacienda finally slept, Petra and Simón stole tools and crawled into the brush. They dug with the frantic devotion of people building an ark before a flood, pausing whenever an owl called too close, freezing whenever a guard coughed in the distance. At first, the hole was shallow, and their hands blistered while their hearts hammered, but gradually the tunnel began to take shape. It descended at a gentle angle so a body could crawl through without breaking bones, and at the end they carved out a chamber, small at first, barely large enough for two adults to sit. Simón stole planks from the stables and, piece by piece, they reinforced the walls so the earth would not collapse. Petra found bamboo and hollow reeds and used them like lungs, running them up through the soil so the chamber could breathe. They covered the entrance with a plank, then with dirt, then with the careful messiness of nature, arranging leaves and stones until it looked like nothing had ever been disturbed.

Four months passed, and Petra’s belly grew beneath loose cloth while the tunnel grew beneath the world. When they finally finished the first chamber, Petra stood over the hidden entrance and felt something she had not allowed herself in years. Hope rose inside her like a dangerous flame.

In November of 1820, Petra gave birth.

She performed illness for the overseers, clutching her stomach in the daylight, groaning softly, claiming cramps, asking permission to lie down. When the night came and the barracks filled with sleep and exhaustion, she slipped out with Simón and crawled into the brush. The tunnel swallowed them, and the air changed. It became cooler, damp, smelling of soil and old roots. At the chamber’s end, by candlelight that trembled like a scared heart, Petra labored in silence.

The child arrived with one small cry, and then, as if the baby understood the rules of survival better than most adults, he quieted. He was a boy, small, healthy, slick with birth, blinking into a darkness he would come to know as home. Petra pressed him to her chest, and tears came, not as noise, but as a hot ache that soaked into her own skin. She named him Luz, Light, a name that sounded like a promise and an insult at the same time.

Before dawn, Petra returned to the barracks, washed herself quickly, arranged her face into emptiness, and went back to work. The overseer noticed her belly was gone.

“What happened?” he asked, annoyed, not concerned. He stared at her like a ledger missing a number.

Petra looked at the ground, then raised eyes that seemed already dead. “The baby was born dead,” she said. “I buried him in the brush.”

The overseer grunted and walked away, because a dead slave infant did not require investigation. There was no profit in grief, and so grief was not worth management. That was how the lie began, a lie fed by cruelty and indifference, a lie Petra would carry for twenty-five years.

Every night after that, Petra crawled down the tunnel to nurse Luz in the darkness. She fed him with her own body, with stolen water, with bits of food Simón managed to bring. She sang in whispers, her voice pressed down small so it could not climb up through the soil. She told him stories about the world above, careful stories that did not make him too hungry for what he could not have, and yet she could not help describing the sun, that enormous warm eye in the sky, because even speaking of it made her feel for a moment that freedom existed somewhere.

Luz grew. He learned to crawl in a space that demanded he keep his body low. He learned to walk with short steps, hands skimming the walls for balance. He learned words not from the chatter of markets or the laughter of schoolyards, but from the voices of two people who loved him enough to build a universe for him out of dirt.

In 1822, Petra became pregnant again.

The process repeated with frightening efficiency: the hidden belly under loose cloth, the secret labor underground, the return to daylight with a dead expression and a dead-baby lie. A daughter was born, and Petra named her Esperanza, Hope, because Petra was building her children a future out of the one thing the hacienda could not count: stubborn love.

Then another child, and another, and another, the years folding into each other like worn cloth. In 1824, a boy named Simón, after his father, arrived into the underground world. In 1826, Consuelo, Consolation. In 1828, Francisco. In 1831, Mercedes. In 1834, Salvador. In 1838, the last, Milagros, Miracles, because by then the miracle was not that Petra kept giving birth, but that she kept everything else from noticing.

With each new child, Petra and Simón expanded the refuge, digging outward, carving a second chamber, then a third, connecting them with narrow passages. What began as one small room became a system, nearly thirty square meters spread into spaces with purpose: one for sleeping, one for eating, one for necessities. Simón deepened the ventilation, adding more bamboo tubes, hiding their ends among the shrubs. He scratched a narrow shaft down toward an underground trickle of water, and over time they turned it into a small well. Petra lined parts of the walls with woven mats to hold warmth, because underground damp could invade bones like a slow punishment.

It was not comfortable. It was not fair. It was not the childhood anyone would choose if they had choices. Yet it was also something the world above would never have allowed them: a family that stayed together.

The older children became caretakers because caretaking was the only way the group could survive. Luz, the firstborn, became a second father long before he became a man, learning how to hush a crying baby, how to share food, how to listen for footsteps above ground. Esperanza became a second mother, her arms always occupied, her voice always soothing, her face always watching the ceiling as if she could will it to stay solid. They invented games that required no open space, games of whispers and memory, games where fingers became actors and shadows became landscapes. They learned to read from a stolen prayer book, tracing letters by candlelight until letters stopped being scratches and became doors. They wrote on the earth walls with sharpened sticks, practiced sums by counting kernels of corn, built maps of places they could not see.

Petra visited every night. That was her rule, her vow made flesh. After midnight, when the hacienda fell quiet, she would slip away, crawl through brush, peel back the hidden entrance, and descend into her second life. She brought food and water, yes, but she also brought stories, because stories were oxygen. She described clouds as floating cotton, trees as green pillars reaching upward, birds as creatures that owned the sky. The children listened with eyes that widened in the dark, eyes that had learned to make the most of limited light. Sometimes they laughed softly, and Petra would press a finger to her lips, and the laughter would shrink back into silence.

Once, when Luz was seven, he asked the question Petra had dreaded.

“Why can’t we go up?” he whispered.

Petra wrapped her arms around him in the darkness and felt how thin he was, how quickly children grew even without sunlight. “Because there are men up there who would take you from me,” she said. “They would sell you. They would make you work until your bones hurt, and they would call it your duty.”

“Why?” Luz asked, because children always ask why, even when the answer is poison.

Petra’s throat tightened. “Because our skin is dark,” she said, “and this world decided that means we are not free.”

“When will we be free?” Luz asked.

Petra did not know. Independence came and went above them like weather, flags changed hands, speeches were made, promises shouted into plazas, but the haciendas remained stubborn, and cruelty found ways to wear new clothes. Petra could only hold her son and say, “Someday,” because someday was the only safe word she had.

Then in 1835, the underground world lost one of its two architects.

Simón died under a horse in the stable, a fast accident with a slow aftermath. One moment he was guiding the animal, the next he was crushed, his ribs folding, his breath fleeing. There was no doctor called for a slave, only a quick removal so work could continue. Petra was told after it happened, as if the news were a minor inconvenience, and something inside her cracked open.

For days she moved like a ghost, cooking, carrying, obeying, while grief thundered inside her chest. At night, she crawled down the tunnel and pressed her forehead to the earth wall and shook silently, because even mourning had to be quiet. The children clung to her in the dark, eight bodies huddling around her like they could protect her from the world above. Luz tried to be strong, but he was still young, and the absence of his father felt like the sudden disappearance of a pillar holding up their ceiling.

Petra did not have the luxury of collapsing. Now she alone carried the secret. She alone stole food, hauled water, hid signs, soothed nightmares, and kept the underground world functioning. Her knees began to fail from the nightly crawling, joints grinding down into pain that never fully left. Her lungs suffered from damp air and candle smoke, and coughing became a dangerous habit she had to swallow back in the hours before dawn.

The children also began to show the marks of their impossible upbringing, not as melodrama, but as quiet distortions. Esperanza dreamed of collapse and woke screaming into the dark, and her siblings learned to cover her mouth gently, urgently, to keep that sound from leaking upward. Simón, the third child, grew quiet, then quieter, until words seemed to abandon him altogether, leaving him staring into darkness as if searching for a door no one else could see. Consuelo tore strands of hair from her head until Petra rubbed stolen ointment into the bald patches and whispered prayers she did not fully believe, because faith was easier when it did not have to do manual labor.

And yet, humanity persisted like a stubborn weed. Francisco sang, his voice a warm thing that filled the chambers with something close to joy. Mercedes became a storyteller, inventing rivers and horses and cities out of syllables, building landscapes no one could visit but everyone could inhabit for a while. Salvador carved figures into the clay walls, animals and trees, faces with eyes wide open, turning their underground home into a museum of longing. Milagros, the youngest, carried a strange brightness, not because she knew more, but because she had known nothing else, and so she trusted Petra’s promise of “someday” as if it were already scheduled.

By 1843, Petra was forty-two, and she had lived nearly half her life in a double existence: slave by day, underground mother by night. Her body was worn down to the truth of it, knees ruined, hands scarred, lungs thin, but her eyes still held a force that frightened even the people who did not understand its origin. That year, Don Hernando Villareal Yuña died of fever at eighty-one, and the hacienda passed to his son, a man who inherited cruelty without inheriting caution.

The new Don Hernando wanted to modernize. He hired an administrator from Mexico City, a man named Ortega who prided himself on numbers, order, and knowing every inch of the properties under his control. Ortega arrived with ledgers and maps and the kind of arrogance that came from believing the world could be understood if it were properly measured. He began inspections, inventories, walks along the edges of fields, notes on repairs, questions about missing tools, and those questions made Petra’s skin feel too tight around her bones.

One afternoon, Ortega wandered behind the barracks into the scrub. Perhaps he was bored. Perhaps he liked proving his thoroughness. Perhaps fate simply decided the secret had lasted as long as secrets were allowed. He noticed the bamboo tubes protruding from the soil like strange plants, too deliberate to be natural, too placed to be random. He crouched, touched one, and felt cool air. Then he paused, because beneath the wind and distant cattle sounds, he thought he heard something else.

Voices.

Not loud, not clear, but human enough to make his spine stiffen.

That night, Ortega returned with the overseer and two foremen. They carried shovels, lamps, and the confidence of men who believed discovery belonged to them. Petra, hearing the commotion, left the kitchen with her heart turning to ice and ran toward the brush, but she was already too late. She saw them dig, saw the plank revealed, saw Ortega’s face as he stared into the dark opening like a man looking into the mouth of a myth.

Ortega crawled in first, lamp held out, his city clothes immediately ruined by earth. The tunnel swallowed him, and for a moment the night held its breath. When he emerged again, his skin looked drained, his eyes wide with a shock that did not fit his careful personality.

“There are people down there,” he said, voice cracked. “Eight. Alive.”

The overseer blinked as if he had misheard a language. “That’s impossible.”

But impossible had been living under their feet for decades.

Men crawled into the tunnel and began pulling Petra’s children out one by one. First came Luz, twenty-three years old, a grown man who had never seen the sun. The lamp light struck his face and he screamed, hands flying to his eyes, body recoiling as if the world itself had punched him. Esperanza followed, shaking violently, hugging herself like she could stitch her skin back together. One after another, they emerged, blinking, crying, gagging on the sudden flood of air and smell and space.

When Milagros came, only five, she did not scream. She stared upward, eyes huge, mouth slightly open, as if wonder had replaced fear in her small body. She saw Petra, collapsed to her knees in the dirt, and she whispered, almost reverently, “Mamá… this is above.”

Petra could not answer with words. Her grief came out as soundless sobs, because the secret was over and the consequences were arriving like a storm.

News traveled faster than mercy. Within days, people came from other haciendas, from towns, from Morelia, from wherever curiosity was fed. Priests arrived to see if the story was a moral lesson. Merchants arrived because suffering always drew a crowd. Journalists arrived because the new Mexico was learning the power of a public scandal. They called Petra’s children “the ghosts of the earth,” and they treated them like miracles and monsters at the same time.

Don Hernando’s son was furious, not because of the pain inflicted on human beings, but because of what the discovery meant in his ledger. Eight slaves unaccounted for, eight bodies that had not produced profit in the way he believed they should have, eight items that had escaped his ownership without his permission. He wanted Petra whipped, wanted the children sold immediately and separately, scattered across Mexico so they would never form a family again. That was his instinct: to destroy the thing that had defied him.

But Mexico in the 1840s was not Mexico in 1820, at least not in public. The idea of slavery was becoming harder to defend in print, harder to praise in speeches, and the story of a mother who had chosen darkness rather than separation did something dangerous. It made people imagine themselves in her place. It made women in good dresses feel nausea at the thought of babies sold like sacks of grain. It made politicians smell opportunity, and priests smell sermons, and abolitionists smell a crack in the wall.

Pressure gathered like rainclouds. The governor’s office took notice. Meetings happened in rooms Petra would never have been allowed to enter. Finally, an informal trial was arranged, less law than spectacle, because the powerful still controlled the stage, but they now feared the audience.

Petra was brought in to testify. She walked with a limp, knees damaged by years of crawling, cough shaking her ribs, hair threaded with gray that had arrived early. Yet when she lifted her face, the room quieted, because her eyes held the kind of force that could not be purchased.

“Why did you do it?” the judge asked, attempting neutrality in a room filled with landowners.

Petra looked directly at him. “Because I am their mother.”

“But you raised them under the earth,” someone protested, disgust disguised as concern. “No sun, no space, no freedom.”

Petra’s head tilted slightly, and when she spoke again her voice did not tremble. “No chains,” she corrected meaningfully. “No whips. No auctions. No strangers taking them from my arms. My children were not sold. My children were not beaten by an owner who called it discipline. They grew together. They protected each other. They learned love from each other. Do you call that nothing?”

A murmur spread, the sound of discomfort, because Petra was not begging. She was accusing.

“You call that freedom?” the judge pressed. “A hole?”

Petra’s gaze moved through the room, taking in the well-fed men, the clean hands, the expensive boots, the people who had never had to choose between two kinds of nightmare. “You call this freedom?” she asked, and the question landed like a stone dropped into still water. “A world where a mother cannot keep her baby? A world where a child is ripped from the breast and sold before it knows its own name? A world where family is a privilege reserved for those with lighter skin and more money? I gave my children the only freedom I could make with my hands. I kept them alive. I kept them together. I kept them mine.”

Her cough rose, and she swallowed it down, refusing to let her body interrupt her testimony. “Was it perfect?” she continued. “No. It was terrible. It hurt them. It hurt me. I regret every day I could not give them the sun. But when they slept, they slept beside their siblings, not beside strangers. When they woke, they woke knowing their mother would come. Tell me, señor judge,” she said softly, “how many mothers in your world can promise that and keep it?”

Silence held the room. Even men who hated what Petra represented found themselves trapped in it, because her logic was simple, and simple logic was a blade.

The case divided the region. Some called Petra a criminal, arguing that she had tortured her children, that she had stolen childhood from them. Others called her a hero, arguing that she had done what no law would do for her, that she had built a refuge when the world offered none. The truth sat between these judgments like a bruise: Petra had been forced into an impossible decision by a system designed to make love a punishable offense.

Under political and public pressure, Don Hernando’s son was forced to free Petra and her children. It was not kindness. It was strategy. Keeping them enslaved risked riots. Selling them risked a scandal that could spread beyond Michoacán. Freedom, in this case, became the least troublesome option for the powerful, and so it was granted like a bone thrown to a dog.

On May 3rd, 1845, Petra and her eight children received papers declaring them free.

The first days under the sun were not the triumph people imagined. Freedom did not immediately transform trauma into happiness. The sunlight hurt their eyes like fire, and some of them could not bear it without covering their faces. Open fields terrified Luz, who had spent his entire life inside walls, and the horizon looked to him like a threat, not a gift. The sound of towns, markets, carts, shouting, music, felt like a storm that never stopped. Esperanza’s nightmares did not disappear; they simply changed shape. Simón, who had stopped speaking as a child, struggled to find words again, as if his voice had been buried too deep to dig out quickly.

Yet they were together, and together became their anchor.

A group of abolitionists, eager to prove that compassion could be practical, helped them obtain a small property outside Morelia, a modest house with land enough to cultivate. The siblings worked side by side, hands in soil that now belonged to them in a way that felt almost unreal. They did not separate, not because they were weak, but because separation had been the weapon used against them, and they refused to give that weapon any new shape.

Slowly, life began to expand. Francisco sang in daylight, and his voice sounded different with wind carrying it, as if the world itself had joined the song. Salvador carved wood instead of clay, making animals that now matched real animals he could finally see. Mercedes told stories to neighbors, and the neighbors listened with tears and disbelief, because it was easier to imagine monsters than to admit the world could force a mother into such choices. Simón became a carpenter, building furniture that felt safe, chairs with solid backs, tables with thick legs, objects that did not collapse, because he needed the reassurance of sturdy things. Luz, the eldest, eventually married a widow who understood his preference for small rooms and dim light, and when he held his own children, he trembled with a mixture of joy and grief, because he finally understood what Petra had been fighting for all those years.

Esperanza never married. She stayed close to Petra as if proximity could repay a debt she did not know how to name. She became the family’s quiet center, organizing meals, tending wounds, holding hands through panic attacks when the world felt too wide. She was the one who reminded them, again and again, that survival was not the same as being finished, and that healing could be slow without being hopeless.

Petra lived only a few more years. Her body had been sacrificed over decades, and freedom arrived too late to repair what crawling through a tunnel every night had done to her bones. In 1852, at fifty-one, she lay dying in the modest house outside Morelia, the sun warm on the wall, the sound of her children moving around her like a protective tide.

They gathered at her bedside, eight adults shaped by darkness and love, and Petra looked at them with eyes that still held that fierce light no one had been able to extinguish.

“It was worth every night,” she whispered. Her voice rasped, but it held no apology. “Every crawl. Every fear. Every minute of that darkness.”

Luz, whose name had been a joke fate played and a promise Petra insisted on keeping, held her hand carefully. “Do you regret anything?” he asked, and the question was not accusation, only the aching need to understand.

Petra’s mouth curved into something almost like a smile. “I regret that the tunnel was not bigger,” she said, and her children broke into sobs that were finally allowed to be loud. “I regret every day I could not give you the sun. But I do not regret saving you. Never.”

She died that night surrounded by the people she had refused to surrender.

They buried her in soil that belonged to them, and on her grave they carved words that did not pretend the story was simple: Petra, mother of eight, dug a hole to give us life. She hid us to save us. She loved us in the dark and taught us that freedom is not only a place, but the right to stay together.

Years later, people still argued about Petra, because people liked judgments that made them feel clean. Hero or monster. Saint or criminal. But her children did not argue. They had lived the alternative. They had seen what happened to babies sold away, to families shredded for profit, to love treated like a weakness that had to be punished. For them, Petra was not a symbol. She was hands that brought food. A voice that brought stories. A body that broke itself into pieces so theirs could stay alive.

And if you sit with the story long enough, the question it leaves behind is not comfortable, not polite, not something you can answer with a clever sentence. The question is what the world does to a person when it takes away every decent choice, and what kind of love grows in the space where choices used to be.

Because Petra did not build an underground world because she wanted darkness. She built it because the world above insisted darkness was the only safe roof her children could have.

THE END

News

All Doctors Gave Up… Billionaire Declared DEAD—Until Poor Maid’s Toddler Slept On Him Overnight

The private wing of St. Gabriel Medical Center had its own kind of silence, the expensive kind, padded and perfumed…

Mafia Boss Arrived Home Unannounced And Saw The Maid With His Triplets — What He Saw Froze Him

Vincent Moretti didn’t announce his return because men like him never did. In his world, surprises kept you breathing. Schedules…

Poor Waitress Shielded An Old Man From Gunmen – Next Day, Mafia Boss Sends 4 Guards To Her Cafe

The gun hovered so close to her chest that she could see the tiny scratch on the barrel, the place…

Her Therapist Calls The Mafia Boss — She Didn’t Trip Someone Smashed Her Ankle

Clara Wynn pressed her palm to the corridor’s paneled wall, not because she needed the support, but because she needed…

Unaware Her Father Was A Secret Trillionaire Who Bought His Company, Husband Signs Divorce Papers On

The divorce papers landed on the blanket like an insult dressed in linen. Not tossed, not dropped, not even hurried,…

She Got in the Wrong Car on Christmas Eve, Mafia Boss Locked the Doors and said ‘You’re Not Leaving”

Emma Hart got into the wrong car at 11:47 p.m. on Christmas Eve with a dead phone, a discount dress,…

End of content

No more pages to load