The Midwife’s Whisper

The scream came from the upper floor of Whitfield Manor, sharp enough to slice through the heavy August air and make every servant in the hallway flinch as if the sound had hands.

Downstairs, the house tried to pretend it was calm.

Men in linen coats hovered near the study with glasses of whiskey they didn’t need. Women in pale dresses sat stiff-backed in the parlor, fanning themselves like the heat had manners and could be shooed away. Someone murmured a prayer. Someone else whispered about first births and how long they could take, the way people spoke about storms that had a schedule.

But upstairs, in the birthing room where the windows were thrown open and still no breeze came in, calm was a fairy tale.

Catherine Whitfield had been laboring since dawn. Sweat slicked her temples and dampened the collar of her nightgown. The sheets beneath her were wrinkled and stained with the evidence of effort, the kind of effort nobody praised once it was finished. She gripped the side rails of the bed as if she could hold herself to the world by force.

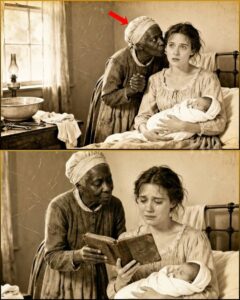

At her side stood Hannah.

Hannah was forty-six years old, though time did not count the same for her as it did for the people who owned clocks. Time, for Hannah, lived in seasons and bodies. In harvests and heartbreaks. In how long it took a wound to scar over, and how quickly a child could be sold away.

She pressed a cool cloth to Catherine’s forehead, turning it gently as a mother might, except Hannah had no legal right to mother anyone in this house. Her hands were capable, practiced, and quiet. Her eyes took in everything.

Two younger enslaved women, Lettie and Pearl, moved like shadows, replacing linens, fetching water, boiling cloths, their faces taut with the same fear that lived in every room that mattered. Not fear of the birth. Hannah feared births the way sailors feared water: it could take you, but it was also where you lived. No, this fear was older, baked into the walls.

Because in this house, a child was not just a child.

A child was an inheritance. A sentence. A promise that the plantation would remain the plantation, that the Whitfield name would keep its grip on 1,100 acres of tobacco land in Albemarle County, fifteen miles from Charlottesville, as if the earth had been deeded to their blood.

Outside, the fields stretched toward the horizon, green leaves heavy on stalks, labor bending human backs into shapes the Bible never described. Thomas Whitfield III owned one hundred and thirty-two enslaved people. On paper, he owned them like he owned horses, carts, and barns.

In the birthing room, it was Hannah who held the only kind of ownership that mattered in that moment: the knowledge of how life arrived.

Catherine’s breath hitched and turned into a cry that became another scream. Hannah braced her hand at Catherine’s lower back, murmuring steady words that sounded like comfort but were also instruction. She watched Catherine’s face, the way a midwife watched weather.

“Again,” Hannah said softly. “When the pain rises, you ride it. Don’t fight the wave.”

Catherine’s eyes flicked toward Hannah’s as if she wanted to hate her for being calm. But then another contraction rolled through her and hate was too heavy to carry.

Downstairs, Thomas Whitfield III paced in his study, because that was what men did. The custom said men didn’t attend births. Custom also said men didn’t do a great many things they still did, once the doors were shut.

Thomas’s mother, Eleanor Whitfield, sat in the parlor with two neighboring plantation mistresses who had come to offer support and, more honestly, to witness. In places like this, support was often just a prettier word for proof.

Hannah remembered Eleanor as a younger woman, years ago, when Thomas Whitfield II still lived, when his voice carried down hallways like a commandment and the household bent around him like grass in wind.

Thomas Whitfield II had been dead since 1843, but death did not erase a man like that. It only moved him into whispers.

Hannah had been purchased by him in 1819, brought from a neighboring plantation because she’d been taught the work by her mother, and her mother had been taught by her grandmother, and somewhere behind that line was West Africa, a place Hannah could not name but could feel in the practices her hands remembered.

She had delivered more than two hundred babies. Enslaved babies in cabins with dirt floors and prayers that sounded like swallowed sobs. White babies in clean rooms where men waited below as if the child belonged to them more than it belonged to the woman who bore it.

Birth made people honest in ways that surprised even Hannah. Labor loosened tongues. Pain pulled secrets out like splinters. Hannah had heard confessions from white women who would rather die than speak those words in daylight. She had seen bruises in places women swore were accidents. She had watched men look at newborn faces with relief that was too sharp, too hungry, as if they were checking for evidence.

And because she was enslaved, people assumed she was simple. They assumed she did not understand what she saw.

That assumption was a kind of blindness Hannah learned to use.

At 4:17 p.m., after nearly ten hours, Catherine’s body made its final, furious argument with the world.

Hannah caught the infant as he slipped into her hands, slick and warm and startlingly alive. She cleared his airway with practiced care. The baby’s cry filled the room, a fierce sound that made Lettie cover her mouth in relief.

“Healthy,” Hannah said. She swaddled the baby in prepared linens, tight enough to comfort, loose enough to breathe.

Catherine sagged back against the pillows, her hair plastered to her cheeks, her eyes dazed and shining. Relief washed over her face the way rain washed dust from a road.

Hannah brought the child closer, and as she cleaned him, her hand stilled.

On the baby’s left shoulder blade, three dark spots arranged in a neat triangle, each about the size of a corn kernel.

For a heartbeat, the room tilted.

The heat in Hannah’s chest turned to ice.

She had seen that mark before.

She had seen it on Thomas Whitfield II, once, when sickness took him and he’d been stripped for bathing, his big body reduced to something human and breakable. The mark had been there, a signature the Lord had written without asking anyone’s permission.

She had seen it again, years earlier, in 1824, on a boy she delivered in the slave quarters, a baby born to an enslaved woman named Ruth. Ruth’s face had been blank with exhaustion and fear, because she didn’t need to ask who the father was. Everyone knew.

And she had seen it that same year, three months later, on a white baby girl delivered at the Blackburn plantation in Buckingham County, thirty miles south. Hannah had been loaned out because the birth was difficult. The mistress, Martha Blackburn, had clutched Hannah’s hand so hard her nails left crescent wounds.

The baby girl had arrived with a head full of dark hair and a mark on her shoulder blade.

Three spots. A triangle.

They called her Sarah Blackburn.

That baby girl was now Catherine Whitfield.

Hannah’s mouth went dry. She adjusted the linens, forcing her hands to behave like nothing had happened. But inside her, years stacked like cordwood and threatened to catch fire.

Thomas Whitfield II had visited the Blackburn plantation in the summer of 1823. Everybody knew because wealthy men traveled with noise, with trunks, with servants. They said it was business. Joint tobacco ventures. Numbers. Deals.

But women noticed different things.

Women noticed when a husband suddenly bragged too much about his guest. When a mistress stopped attending social calls and claimed illness for months. When a child arrived nine months later with a mark that didn’t belong to the household’s history.

Hannah had carried the truth for twenty-three years, not because she enjoyed holding it, but because truth was dangerous in her hands. An enslaved woman’s truth could get her sold. Could get her whipped. Could get someone she loved punished just for existing near her.

So she stayed quiet.

She watched Sarah grow up from a distance during the times she was loaned out, watched the girl learn to smile with teeth that had never tasted the inside of a cabin, watched her become a young woman who believed her own story because believing was safer than doubting.

Then Sarah Blackburn married Thomas Whitfield III in June 1844, and Hannah stood at the edge of the wedding reception in the main house, serving food and watching the bride dance with her new husband while white men toasted family unions and legacy.

Hannah watched the bride laugh and thought, They are clapping for a wound.

Nobody questioned the match. Why would they? Two prominent Virginia families joining through marriage was what the county expected. The kind of marriage that kept land and power braided together.

Only Hannah knew the braid was made of blood that shouldn’t have touched.

Now Hannah held that marriage’s child, and the mark on his shoulder was a cruel little witness.

Catherine reached out with trembling arms. “Let me see him.”

Hannah placed the baby into Catherine’s hands. Catherine’s face softened as she counted fingers and toes, examined the child’s nose, his lips, his full cheeks. She smiled, exhausted and proud, the way a person smiled when she believed life was finally giving her what she’d earned.

Thomas Whitfield III entered the room without waiting for permission.

He moved quickly, his boots loud on the wooden floor, his face bright with triumph. He ignored custom because custom did not matter when a man wanted to claim what he believed belonged to him.

“My son,” he breathed, as if saying it would make it truer.

Catherine tried to sit up. “Thomas, you’re not supposed to…”

He laughed, and it was an easy laugh, the kind that came from never needing to fear consequences. He took the baby from Catherine’s arms, held him up toward the lamplight, and said, “Perfect. Look at him. The Whitfield line continues.”

Hannah watched his fingers support the infant’s back. She watched his face, searching for any flicker of recognition.

Nothing.

Of course nothing.

A man like Thomas did not look at a birthmark and see a warning. He saw only proof of survival, proof of ownership.

Downstairs, celebration swelled. Whiskey poured. Plates clinked. Neighbors congratulated Eleanor Whitfield in the parlor as if she had personally delivered the child through sheer will.

Upstairs, Hannah and the girls cleaned the room. Blood and sweat disappeared beneath fresh linens as if pain could be scrubbed away with soap.

Catherine ate broth. Thomas kissed her cheek and told her she had done well, like she was a horse that had carried him home.

The baby slept, tiny fists curled.

By the time the sun fell and the last of the initial chaos settled, Thomas returned downstairs to entertain. Eleanor’s voice drifted upward as she hosted.

And for a brief moment at 7:30 p.m., Catherine was alone.

The room was quieter now, the heat still thick but no longer frantic. Candlelight flickered against the walls. Catherine cradled her son, her eyes heavy, her face pale in the dim glow.

Hannah entered carrying a fresh cloth and a cup of water.

She paused at the doorway.

She had choices.

Silence was safer. Silence was what she had practiced like prayer for twenty-three years. Silence meant she might live out her days in the same quarters, close to the grandchildren she had managed to keep near her, close to the women who trusted her hands to bring life into a world determined to crush it.

But silence also meant watching this child grow into a man who would inherit land and bodies, who would never know the poison in his bloodline, who would be taught that the world was arranged correctly because God and law said so.

Silence meant swallowing the truth until it rotted inside her.

Hannah stepped closer. Catherine didn’t look up at first. She rocked the infant gently, humming a tune Hannah recognized as a hymn, though the melody was so soft it could have been a lullaby.

Hannah set the cup down.

Catherine finally lifted her gaze. Her eyes were red-rimmed but calm. “He’s beautiful,” she whispered.

“Yes,” Hannah said.

The baby stirred, and the blanket shifted, exposing the left shoulder blade.

Three spots. Triangle.

Hannah felt the truth rise in her throat like bile.

She leaned close, not close enough to be obvious if someone glanced in, but close enough that her voice could fit inside Catherine’s ear.

The words came out in a breath, quick and quiet, like a prayer spoken over a grave.

“Your husband’s father… is your brother.”

Catherine went still.

For a second, Hannah thought Catherine hadn’t heard her. Then Catherine’s fingers tightened around the baby, not hard enough to hurt him, but hard enough to show that her body had understood the shock before her mind could.

Catherine turned her face toward Hannah. “What did you say?”

Hannah’s heart hammered. She had crossed a line she could never uncross.

But she didn’t repeat it. Repeating would make it bigger, louder, easier to catch. Hannah simply met Catherine’s eyes, and in that gaze was the weight of everything Hannah had learned about white women: how they could be cruel, how they could be kind, and how often they were trapped inside cages built from lace and law.

Catherine’s lips parted. Then she shook her head once, sharply, as if shaking could dislodge the words.

“That’s… that’s nonsense,” she whispered. “You’re tired. You’ve been working all day.”

Hannah nodded as if she agreed. “Drink your water, ma’am.”

And then Hannah left, carrying her own heartbeat like contraband.

That night, in the quarters, the air was thick with gossip and caution. The news of the heir’s birth traveled fast. Women who had served in the main house heard laughter, smelled whiskey, counted how many plates went back upstairs.

Lettie told Pearl that Hannah had looked strange when she cleaned the baby.

Pearl told Lettie to keep her mouth shut.

Hannah sat on the edge of her bed, hands resting on her knees, and listened to the night sounds: insects, distant frogs, a muffled shout from the overseer’s cabin, the faint clink of glass from the big house.

Truth, Hannah knew, did not move in straight lines. Truth moved like smoke. It found cracks. It slipped under doors.

In the days that followed, Catherine acted like a woman trying to hold onto her life by pretending nothing had changed.

She smiled when Eleanor visited. She allowed the nurses to take the baby when she slept. She accepted congratulations from neighbors as if their words didn’t scrape her skin.

But when Catherine was alone, she looked at the birthmark.

At first, she did it like curiosity. Like a mother admiring a feature.

Then she did it like someone checking a wound.

Then she did it like someone reading a verdict.

On the tenth day after the birth, a letter arrived from Buckingham County. Catherine’s mother, Martha Blackburn, had written back in response to Catherine’s careful question about childhood features. Catherine’s hands trembled as she unfolded the paper.

Martha’s handwriting was neat, familiar, motherly.

Yes, the letter said. Sarah had a mark as an infant. Three spots in a triangle, left shoulder blade. It faded some with age, but it never vanished.

Catherine read the sentence three times. Then she sat very still, the way people sat when their world broke but no sound came with it.

After that, Catherine’s questions sharpened.

She asked Eleanor at tea, casually, whether the Whitfields had any distinctive family marks.

Eleanor frowned. “Marks? What sort of marks?”

“Birthmarks,” Catherine said, forcing a lightness she did not feel. “My son has a little mark. I wondered if it came from the Whitfield side.”

Eleanor waved her hand. “All babies have something. A dimple, a freckle, some little blemish that disappears. It means nothing.”

Catherine’s smile stayed in place, but her stomach turned.

She began slipping into Thomas’s study when he was occupied in the fields. She looked through papers she once considered boring, the kind of documents that made plantations run: ledgers, travel logs, correspondence.

The plantation’s visiting record from 1823 listed Thomas Whitfield II’s trip to Buckingham County. Three months at the Blackburn plantation. Late spring into summer.

Catherine’s mother had claimed illness that same year, a long absence from social events that Catherine barely remembered but now replayed in her mind with new shape.

Catherine found a letter from her mother to a friend written in late 1823. The phrasing was careful, but fear leaked through the lines. A pregnancy that had caused “considerable anxiety.” A sense that Martha was watching her own life balance on a knife’s edge.

Catherine’s hands shook as she put the paper back. She felt as if the house was narrowing around her, walls leaning in, the air thickening.

Thomas, meanwhile, believed his wife was simply overwhelmed. He told neighbors she was delicate. He told Eleanor that Catherine needed time. He summoned a physician when Catherine’s appetite vanished and her sleep became fractured and thin.

Dr. Morton from Charlottesville examined Catherine and spoke about nerves, about post-childbed melancholy, about women’s minds being fragile after birth. He prescribed rest and laudanum, as if drugging a truth could make it untrue.

Hannah watched Catherine unravel from a distance.

From the outside, it looked like sadness. A new mother who couldn’t find joy.

From the inside, Hannah suspected it felt like drowning.

One afternoon in late September, Catherine came to the kitchen house. Her face was pale beneath her bonnet, her eyes too bright. She dismissed the other servants with a gesture that made them scatter. When she and Hannah were alone, Catherine’s voice dropped.

“You said something to me,” Catherine whispered. “In the birthing room.”

Hannah kept her face neutral. Neutral faces were armor. “You were exhausted, ma’am.”

Catherine stepped closer. “Don’t lie to me.” Her breath trembled. “How do you know?”

Hannah’s chest tightened. She had known this moment would come, or she had at least feared it. Fear and expectation were siblings.

Hannah glanced toward the door, listening for footsteps.

Then she told the truth the way enslaved people told truth: carefully, with the awareness that every sentence could be a rope.

“The mark,” Hannah said softly. “Three spots.”

Catherine’s eyes flicked down as if she could see the baby’s shoulder through walls.

“I saw it before,” Hannah continued. “On your husband’s daddy. On a boy in the quarters. On you, when you was born over at Blackburn’s.”

Catherine’s lips parted, but no sound came.

“I delivered you,” Hannah said. “They loaned me out. Hard birth, your mama needed help. You came with that mark.”

Catherine took a step back, as if distance could protect her.

“And the boy?” Catherine asked, voice barely audible.

Hannah hesitated. Saying names was dangerous. Names made people real, and real people could be punished.

“Ruth’s boy,” Hannah said at last. “Jacob. He’s out in the fields now.”

Catherine blinked, confusion crossing her face. “Jacob is… what does he have to do with this?”

Hannah swallowed. “Same mark. Same daddy.” She looked Catherine in the eye. “Your husband and you, you got the same father.”

Catherine’s hand flew to her mouth. Her eyes filled, but she didn’t cry. Her face went tight with the effort of holding herself together.

“Who else knows?” Catherine whispered.

“Enslaved folks talk,” Hannah said. “But talk don’t mean nothing to white ears. And it ain’t safe to talk loud.”

Catherine’s gaze sharpened. “My mother would know.”

Hannah didn’t answer. She didn’t need to.

Catherine stood there for a long moment, staring at Hannah like Hannah was both a weapon and a mirror. Then Catherine turned and left without another word.

For weeks, Catherine moved like a woman haunted. She did not attend social gatherings. She avoided Thomas’s touch. She held her baby and looked at him as if she were afraid of what she might see in his future.

Thomas grew frustrated. He complained that Catherine was distant. Eleanor suggested Catherine was unwell in spirit. Nobody guessed the truth, because the truth was unthinkable to people who benefited from pretending the world made sense.

Catherine’s investigation continued. It stopped being a question and became a hunt.

Then, in early November, Catherine wrote a letter to her mother.

Not the careful, light letter of a dutiful daughter. This letter was a blade wrapped in paper.

Was Thomas Whitfield II the biological father of Sarah Blackburn?

Catherine did not send it through regular post. She entrusted it to an enslaved messenger who knew the road between plantations and knew what it meant to keep his mouth shut.

Three days later, the response arrived.

Catherine locked herself in her room to read it. Hannah did not see the letter, but she saw the result: Catherine’s face, drained of color, her hands shaking like she had fever.

The confession in Martha Blackburn’s handwriting confirmed what Hannah had known in her bones.

An affair in the summer of 1823. A pregnancy. A desperate attempt to make Henry Blackburn believe the child was his.

A marriage in 1844 that should never have happened.

A mother who had known and stayed silent.

When Catherine emerged from her room, she moved differently. The fog of despair had burned away. What remained was rage so clean it looked almost like calm.

The Whitfields planned the baby’s baptism for November 14th. A gathering. A celebration. A public blessing that would seal the child into society like wax pressed into a letter.

Catherine waited.

Hannah understood what waiting meant.

On the morning of the baptism, the manor swelled with guests. Carriages rolled up the drive. Ladies stepped down in gloves and silk. Men greeted Thomas with firm handshakes and easy laughter, as if the world was stable and good.

In the parlor, the Episcopal minister spoke warmly about family and God’s favor. Eleanor Whitfield stood proud, holding the baby in lace as if she were presenting a trophy.

Catherine sat very still.

Her son’s shoulder blade was hidden beneath fabric. Her face was composed.

But Hannah, serving at the edge of the room, could feel the air changing the way she could feel a thunderstorm before it arrived.

When the minister lifted his hands to begin, Catherine stood.

A hush fell, because plantation society did not like surprises from women.

“Before you bless my son,” Catherine said, her voice quiet but clear, “you must know what you are blessing.”

Thomas frowned. “Catherine, what are you doing?”

Catherine stepped forward, and she reached for her baby.

Eleanor pulled back instinctively. “She’s unwell,” Eleanor said too quickly. “She needs rest.”

Catherine’s smile was thin. “No,” she said. “I need truth.”

She turned the baby slightly, exposing the left shoulder blade.

Three dark spots. Triangle.

A few women leaned in, curious. One man chuckled politely, as if this were a harmless maternal display.

Then Catherine reached into a folder she had tucked beneath her shawl and withdrew papers.

Travel records. Letters. Her mother’s confession, the ink still dark enough to look fresh.

Thomas stepped toward her. “Put that away.”

Catherine did not flinch.

She held the papers up like scripture and said, “Thomas Whitfield the Second was my father.”

The room froze. A fan stilled mid-sweep. The minister’s hands lowered as if prayer itself had been interrupted.

Catherine’s eyes swept the faces around her, and her voice rose just enough to carry. “That makes Thomas Whitfield the Third not just my husband.” She swallowed once, hard. “It makes him my brother.”

Then she spoke the line that landed like a hammer on marble: “Blood doesn’t obey your laws.”

Chaos arrived instantly.

Thomas shouted. Eleanor cried out that Catherine was mad. The minister stammered about needing time, needing guidance, as if God had misplaced his words.

Some guests backed away as if scandal were contagious. Others demanded proof. A few looked at the birthmark again, and their faces shifted in a way that suggested they knew more than they ever admitted.

And then, because Catherine understood how power worked in that room, she did something even more dangerous than speaking.

She pointed toward Hannah.

“This woman delivered me,” Catherine said. “She delivered my husband’s half-siblings in the quarters. She has seen what you pretend doesn’t exist.”

Eleanor’s face hardened. “Remove her.”

But Catherine’s voice cut through the motion. “No. You will listen.”

Hannah’s legs felt heavy. She could taste fear, metallic on her tongue. She knew what this meant for her. She also knew what silence had meant for twenty-three years.

So when Catherine called her forward, Hannah stepped into the center of the parlor.

Every eye landed on her like weight.

Hannah spoke carefully, not because she was unsure, but because she understood the cost of each syllable.

She described the birthmark. She described the two babies born in 1824, one in the slave quarters, one at Blackburn’s. She described Thomas Whitfield II’s mark. She said just enough to make the truth unavoidable.

The gathering dissolved like sugar in water.

The minister refused to baptize the child. Eleanor ordered servants to escort guests out. Thomas locked himself in his study with whiskey and rage.

That night, Whitfield Manor felt less like a home and more like a courtroom without a judge.

The next weeks moved fast and slow at once.

Fast, because gossip traveled quicker than horses. Enslaved people carried the story between plantations the way they carried songs, encoded and persistent. White servants passed it along at market. Planter families wrote letters that hinted and circled and still landed sharp.

Slow, because scandal did not resolve itself neatly. It lingered, fermented, became something people whispered about in church pews and behind curtains.

Henry Blackburn, Catherine’s legal father, suffered what neighbors called an apoplexy and died on December 3rd, 1847. The official cause was natural. Everyone understood the unofficial one.

Catherine was blamed for his death, as if truth were a weapon she had chosen for sport instead of survival.

Eleanor demanded Catherine leave the plantation. Thomas refused to speak to his wife except through clenched teeth. He began quietly seeking legal ways to erase her influence, to paint her as unstable.

Catherine refused to leave without her son.

And Hannah, who had started this by whispering seven words in a birthing room, knew what the Whitfields would do to remove the source of inconvenient knowledge.

In January 1848, Thomas arranged Hannah’s sale.

They said it was for “discipline.” They said it was necessary.

Hannah stood in the yard with a small bundle of cloth that contained everything she was allowed to keep. The slave trader’s wagon waited like an open mouth.

Women in the quarters wept silently. Men stared at the ground. Hannah’s grandchildren clung to her skirt until an overseer pried them away.

Hannah did not scream. She would not give them that.

She turned her face toward the big house and saw Catherine at an upstairs window, pale and still, holding the baby close. For a moment, their eyes met across the distance.

Hannah lifted her chin once, a gesture small as a breath.

I told the truth, it said. Now carry it.

Then the wagon rolled out.

Hannah’s world became roads and new fields, Mississippi soil, a different plantation with the same cruel math. She kept delivering babies because her hands did not know how to stop. She kept listening, because listening was what kept people alive.

Catherine fought for her son in Albemarle County Court. The judge acknowledged the evidence. He did not deny the truth.

But the court punished Catherine for speaking it. For humiliating the family. For writing letters north, letters that hinted at the system’s rot.

In July 1848, custody was granted to Thomas. Catherine was given limited visiting rights and forbidden from discussing the circumstances of the child’s birth. Her marriage was annulled, declared as if it had never existed, leaving her son technically illegitimate despite being born during a legal union.

Catherine left Virginia in August 1848 for Philadelphia.

She carried no furniture, no comfort, no protection except stubbornness. She began writing under pseudonyms for abolitionist publications, describing the way slavery corrupted everything it touched: marriage, motherhood, faith, even blood.

She became, in the North, a woman who had broken her own life open to show what was inside.

In the South, she became a warning.

Hannah lived long enough to see emancipation. When the war ended and freedom arrived like a fragile bird, she did not celebrate loudly. She had watched too many promises turn into traps.

But she did something she had never been allowed to do.

She spoke without whispering.

She testified to Freedmen’s Bureau representatives about the births she had attended, the marks she had seen, the secrets plantation society built itself on.

Her words were recorded. Not honored. Not widely read. But written down.

Catherine died in Philadelphia in 1862, before she could see the war’s end. She never saw her son again. The letters she wrote to him were intercepted and destroyed, because even ink was dangerous.

The boy, raised under a carefully edited story, grew up in Massachusetts, changed his name, built a life far from Virginia’s smoke and shame. He married. He had children. He tried, in his own way, to outrun the past.

But the past is patient.

Decades later, long after Whitfield Manor’s tobacco fields were quiet, long after the men who had once toasted legacy were dust, the truth remained preserved in the places powerful people forgot to check.

In a court record that didn’t explain enough.

In an abolitionist paper that used a false name.

In a Freedmen’s Bureau testimony signed by a woman whose hands had caught hundreds of lives.

And if you listened closely, beneath all the official histories that tried to smooth the story into something polite, you could still hear the quietest sound that ever toppled an empire.

A midwife leaning close.

A whisper.

A truth that did not ask permission.

THE END

News

“Papa… my back hurts so much I can’t sleep. Mommy said I’m not allowed to tell you.” — I Had Just Come Home From a Business Trip When My Daughter’s Whisper Exposed the Secret Her Mother Tried to Hide

Aaron Cole had practiced the homecoming in his head the way tired parents practice everything: quickly, with hope, and with…

“He removed his wife from the guest list for being ‘too simple’… He had no idea she was the secret owner of his empire.”

Julian Thorn had always loved lists. Not grocery lists, not to-do lists, not the humble kind written in pencil and…

HE BROUGHT HIS LOVER TO THE GALA… BUT HIS WIFE STOLE ALL THE ATTENTION….

Ricardo Molina adjusted his bow tie for the third time and watched his own reflection try to lie to him….

Maid begs her boss to wear a maid’s uniform and pretend to be a house maid, what she found shocked

Brenda Kline had always believed that betrayal made a sound. A scream. A slammed door. A lipstick stain that practically…

Billionaire Accidentally Forgets $1,000 on the Table – What The Poor Food Server Did Next Shocked…

The thousand dollars sat there like a test from God himself. Ten crisp hundred-dollar bills fanned across the white marble…

Baby Screamed Nonstop on a Stagecoach Until a Widow Did the Unthinkable for a Rich Cowboy

The stagecoach hit a rut deep enough to feel like the prairie had opened its fist and punched upward. Wood…

End of content

No more pages to load