Extra Chapter: The Day Philadelphia Wore Black

My mother used to say our family did not arrive in Philadelphia on a road. We arrived on a sentence. A sentence written in ink my grandfather feared, signed with the kind of hand that had always been used to command. In our house, the past never stayed politely in the past. It drifted through the rooms like coal dust, settling on bookshelves, on the edge of my father’s anvil, on the white gloves my mother wore when she wanted to feel like a lady and not a lesson.

I was seven when the whole city went quiet in the strangest way. April of 1865. The war was coughing out its last smoke, and hope had begun to walk around like it belonged to everyone, until the news came that President Lincoln had been killed. I remember the morning, because even our street sounded different. Doors closed softly. Horses stepped like they were ashamed of their own hooves. Men who usually argued about prices at the market spoke in lowered voices, as if grief could be startled.

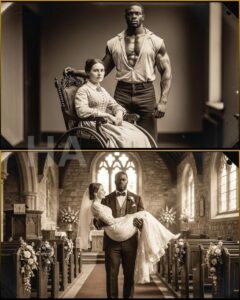

My father stood at the window of Freeman’s Forge, his apron still on, his hands blackened from work. He did not say much, only turned the newspaper so my mother could read the headline herself. My mother’s face tightened the way it did when she was trying not to let the world steal her composure. Then she looked at him, and he looked back, and a decision passed between them without a single word. By midday, we were on the move toward Independence Hall, my mother’s chair rolling over cobblestones, my father pushing with careful strength, my brothers holding my hand like they could keep me from falling into history.

Philadelphia had dressed itself in mourning. Black cloth hung from shopfronts. Dark ribbons trembled from lampposts. Even the vendors at the corners seemed subdued, though a man still sold pretzels because hunger does not pause for tragedy. We passed a Quaker woman in plain gray, face calm as winter light, and a pair of Irish laborers who stared too long at my father’s skin and my mother’s white gloved hands. Their eyes carried an old, ugly question: what are you doing together? My father did not flinch. He simply tightened his grip on the handles of the chair, as if every mile north we’d traveled had trained him in a new kind of steadiness.

The line to enter Independence Hall stretched like a river of people, slow and solemn. Union soldiers stood along the edges, their blue coats turning the crowd into something organized, something that could be contained. I saw Black men in their Sunday hats, women in shawls, children with red noses from the cold. I saw white clerks with stiff collars, German butchers, seamstresses, dockworkers. Grief had made neighbors out of strangers, at least for that hour. A woman behind us offered my mother a warm brick wrapped in cloth for her lap, an old trick for keeping heat when April still pretended to be winter. My mother thanked her with the kind of grace that did not ask permission to exist.

Inside, the air smelled of wax and damp wool and human breath held too long. We moved inch by inch past the walls where freedom’s words were displayed like sacred artifacts. I remember being confused by that, even then, because the building felt like a shrine to a promise that had not been kept. My father lifted me so I could see over shoulders, but his hand trembled, not from weakness, from emotion he had never been allowed to practice openly.

When we reached the casket, my mother’s face changed. Not to softness, not to theatrics, but to something fierce and private. She took my father’s hand, and she held it in front of everyone, right there in that hall, as if she were daring the world to deny what it could plainly see: a scarred Black hand and a pale hand clasped together, equal in grief, equal in dignity. My father bowed his head. My mother whispered something I could not hear. Years later she told me it was a prayer, not for the president alone, but for the kind of country he had tried to drag into daylight.

On the way home, the city’s sadness began to thin into anger. People argued in corners about what would happen next, about whether the new freedom would be real or only a different kind of cage. My father bought a small bundle of flowers from a girl whose fingers were stained with dye, and he laid them at the edge of a church fence because he could not lay them at the nation’s feet. “For the idea,” he said quietly when I asked why. “Not just the man.”

That night, our house smelled of stew and smoke and something else, a kind of stubborn tenderness. My mother sat at the table with her ledger open, not because money mattered more than mourning, but because order was how she fought despair. My father went back to the forge. Grief, for him, always moved through work. The anvil rang, a sound that did not fit the city’s silence, but belonged to our home the way breathing belongs to a body.

Later, when the lamps were low, I crept to the doorway and watched him shape a piece of iron no bigger than my palm. He hammered slowly, thoughtfully, as if each strike were a sentence he was careful not to waste. When he noticed me, he did not scold. He knelt so his huge frame lowered to my height and held up what he was making: a small hinge, delicate as a leaf’s vein. “For your mother’s braces,” he said. “To help the joint move without biting.” I did not fully understand then, but I felt the tenderness inside the engineering. Love, in our family, often arrived disguised as a tool.

The next Sunday, we went to Mother Bethel, the African Methodist Episcopal church where hymns rose like smoke and refused to be ashamed. My mother listened, eyes shining, while my father sang softly, the words fitting him like a coat he had finally been allowed to wear. After service, an older man who had once been enslaved shook my father’s hand and said, “We heard you took your freedom and made a life with it.” My father answered, “Freedom took me too. It took me and didn’t drop me.” Then he looked at my mother, and my mother looked back, and I saw what their love really was: not romance floating above the world, but a daily, determined act of building.

That is the part people miss when they talk about our story as if it were a miracle that happened once and then sat still. The miracle was not a single decision, not a single escape, not even a single kiss in a library. The miracle was that, in a country learning how to mourn and how to change at the same time, two people kept choosing gentleness over fear, dignity over shame, and imagination over the old, rotten rules.

When I became a woman, I learned that history is often a loud thing, full of speeches and battles and official ink. But the truest revolutions I have known happened in quieter places: a hand held in a hall where it was dangerous to hold it, a warm brick offered to a stranger, a hinge forged late at night so a woman could stand again. If you want to know what love can do, do not only look for it in grand declarations. Look for it where it sweats, where it learns, where it lifts. Look for it where iron becomes something kinder than its own nature.

News

Dad Daddy, I’m So tired … Can I Sit With You?”— The Poor Girl’s Question Made The Billionaire Cry

For a moment, she just breathed, lungs working hard under her ribs. Her eyes, dark and too old for her…

They Laughed when Newly Divorced Man Inherited His Grandpa’s Old Cabin, Then Everything Changed.

He found his cofounders in the glass conference room. They were sitting close together, like a family in a photograph….

“Your Blind Date Didn’t Show Up Either?”—A Single Mom Whispered To A Sad Millionaire CEO

Michael surprised himself by letting out a breath. “I’m Michael.” She hesitated, then offered her name like it wasn’t a…

They Called Her the Poor Little Rich Girl, Until She Sewed Her Name Into the World

Her mother, Lillian Hartley Vance, wore grief like a dress she eventually outgrew. Lillian was beautiful in the way people…

After The Billionaire Father Died, The Stepmother Cast Her Out — Unaware She Was The Rightful Heir

Thunder cracked like a gavel somewhere far off. The guard’s hand closed around Brielle’s elbow, not rough, not tender, simply…

The CEO went to his adopted daughter’s school during lunchtime — what he witnessed shocked him.

Nia stared out the window, shoulders drawn inward. When the school came into view, red brick and a fluttering flag,…

End of content

No more pages to load