They called her the silent ghost of Bitter Creek County, the girl who never spoke and never cried, even when the world tried its hardest to grind her down into dust. In Copper Ridge, Wyoming Territory, silence wasn’t a virtue, it was a vacancy, a blank space people felt entitled to fill with their own worst ideas. And Lila Crowley had learned, year by year, bruise by bruise, that silence could be armor if you wore it like iron. The trick was to let them believe you were broken in a way that made them look away, because the kind of men who loved power always preferred a victim who couldn’t testify.

On a freezing night in 1874, winter clawed at the town like a hungry animal, and the Spur & Lantern Saloon crouched against the wind with its crooked timbers and yellow lamplight leaking into the street. Inside, heat and stink fought for dominance: smoke from cheap cigars, sweat ground into wool coats, and sour whiskey spilled so often the floorboards had permanently surrendered. Men crowded around card tables and a chipped piano, laughing loud enough to drown their own consciences. Lila stood near the central oak table, wrapped in a ragged shawl that did nothing against the cold that lived in her bones, her hands clenched tight under the cloth as if she could hold herself together by force.

Her father, Amos Crowley, was on top of that table, swaying with a bottle in one hand and mud still caked on his boots. He had the flushed, watery face of a man who drank to forget that he was the author of his own misery. When he kicked a glass off the edge and it shattered near Lila’s bare feet, she didn’t flinch. She stared down at the sawdust, expressionless, as if nothing in the world could touch her anymore. The room quieted in a slow ripple, not out of respect, but out of curiosity, the way predators pause when something wounded stumbles into open ground.

“I said… who wants her?” Amos shouted, voice slurred, cracking on the words like old wood. “She’s strong. She cooks, cleans. Don’t talk back. Not a word.” He spread his arms as if presenting a prize he’d won, not a daughter he’d raised. “Best part? She’s deaf. Deaf as a post. Can’t hear you. Can’t tell nobody what you do.”

A chuckle rolled across the saloon, low and ugly, and Lila felt it in the muscles of her back like a hand pressing her down. She didn’t look up. That was the rule. Eyes invited attention, and attention invited pain. She had learned that long before she learned how to bake bread. Before she learned how to lift a bucket without spilling. Before she learned how to swallow her own voice so completely that even she sometimes forgot it existed.

From behind the bar, the bartender, a heavy man everyone called Doc Rudd, scowled and slammed a rag onto the counter. “Sit down, Amos. You’re making a fool of yourself.”

“I need money,” Amos snapped. It wasn’t a confession, it was a complaint, as if the world owed him the coins he’d squandered. He reached down and grabbed Lila by the hair, yanking her head back so hard her neck strained. A few men leaned forward, amused. Lila made no sound. Her eyes stayed flat and empty, fixed on the ceiling beams like they were something to count, something safe.

“Look at her,” Amos crowed. “Pretty enough if you scrub her clean. And she don’t scream. Don’t beg. Ain’t that right, girl?”

He shook her again, testing whether she would break. Lila let her body go still and heavy, the way she had learned to do on nights when his anger came home before he did. She wasn’t deaf. She wasn’t broken in that way. But pretending to be deaf had made her invisible to the kind of cruelty that hunted words. Silence had become a locked door, and behind it she had kept the memory of her mother’s last breath, the sound of a chair overturning, and her father’s voice roaring like a storm inside their one-room shack.

A voice from the corner cut through the room, sharp with entitlement. “Ten dollars.”

The man who stepped forward was Bart Vane, foreman for the Kessler Cattle Company, a scar-faced brute with hands like shovels and eyes that never softened. The scent of tobacco and gun oil clung to him, and Lila’s stomach tightened because her body remembered what her mind tried to bury: stories whispered too late, women who vanished, bruises explained away as clumsiness. Bart moved closer, and Lila—careful, disciplined—did nothing but breathe.

“Fifteen,” Bart said, stopping close enough that his shadow fell over her. He reached out as if she were a tool to inspect, fingertips angling toward her chin.

“Sold!” Amos barked, triumphant, like he’d closed a good deal. “Take her. She’s deaf.”

Bart’s hand closed around Lila’s arm.

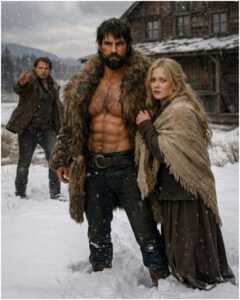

The saloon doors slammed open, and winter crashed inside as if it had been waiting for permission. Snow spiraled across the floorboards, snuffing lamps near the entrance, and men cursed as the cold slapped their faces. In the doorway stood a figure so large and fur-wrapped he seemed carved from the mountain itself. Buckskin and furs layered his body, snow clung to a dark beard, and a rifle rode his shoulder like it belonged there. A long knife sat strapped to his thigh, the kind that didn’t exist for show.

Rowan Cade had arrived.

The room shifted, the way it does when an old story walks back into town. Some men remembered him as a trapper who could vanish for months and return with pelts and gold dust. Others remembered harsher rumors: that he’d been a ranger once, that the war had taken something from him that never grew back, that he lived alone above the tree line where only wolves argued with the wind. Whatever they believed, they moved out of his path without thinking too hard about why.

Rowan walked to the bar, set a heavy leather pouch down with a dull thud, and said in a voice that didn’t waste breath, “Whiskey.”

“We’re busy,” Bart snapped, tightening his grip on Lila as if she might evaporate.

Rowan turned slowly. His gaze went to Bart’s hand, then to Amos on the table, then to Lila’s face. He didn’t look at her like a commodity. He looked at her like a person standing in the middle of a fire.

“Let her go,” Rowan said.

It wasn’t loud. It didn’t need to be. Something in the calm of it made the air feel thinner.

Bart’s grin twitched. “I bought her. Her father sold her.”

“She ain’t cattle,” Rowan replied, stepping forward. “And you ain’t buying a soul tonight.”

Amos, sensing an argument he might profit from, puffed up. “I’m her father. I can do what I please.”

Rowan reached into his coat, pulled out a raw gold nugget the size of a small fist, and tossed it. It hit Amos in the chest and dropped into his lap with a weight that made the table creak. The room gasped, not in awe of beauty, but in recognition of value. Gold didn’t just shine, it changed rules.

“That’s worth five hundred dollars in Cheyenne,” Rowan said, eyes never leaving Bart. “I’m paying whatever debt you think you’re settling. She’s free.”

Lila’s head lifted for the first time that night, not because she wanted to, but because the word free landed in her like a stone in a pond. Her eyes met Rowan’s, and what she saw there wasn’t softness. It was tiredness. Haunted, yes, but not cruel. The kind of gaze that had seen what men became when no one stopped them.

Rowan shifted toward her, just enough to make a path. “Come with me,” he said, quieter now. “Or stay here. Your choice.”

Choice. It was a strange word, unfamiliar as a song she’d never heard.

Lila did not hesitate. She tore her arm from Bart’s grasp and stepped toward Rowan before fear could argue. Behind her, Amos laughed, the sound wet and bitter. “She can’t hear you! She’s broken!”

Rowan didn’t answer him. He didn’t explain. He simply guided Lila out into the blizzard, lifted her onto a mule waiting near the hitching post, and wrapped her in a heavy buffalo robe that smelled faintly of smoke and pine. His hands worked quickly, tying straps, checking knots, moving with the practical competence of a man who expected the world to try to kill him.

As the wind screamed around them, Rowan leaned close, mouth barely moving.

“I know you can hear.”

Lila froze so hard she felt her own heartbeat stumble. For three years she had not spoken, not since the night she watched her father beat her mother to death and realized that sound could betray you. Her silence had been her shield, her lie her lock. No one had ever seen through it. Not Amos. Not the men who mocked her. Not the women who pitied her from a distance. But this stranger, this mountain man, had noticed something as small as an ear twitch.

Rowan straightened and began leading the mule up into the dark without waiting for her answer, as if he’d said something as ordinary as the weather.

The climb lasted two brutal days. The trail narrowed into a ribbon carved into sheer rock, and the world below became a blur of white and black. Lila rode in silence, her body aching, her mind racing to keep pace with her fear. Why had he saved her? Why had he paid gold for a girl he didn’t know? And why, if he knew her secret, had he chosen to protect it instead of exposing her in front of the saloon like a magician revealing a trick?

They camped the second night in a shallow cave that smelled of old animals and wet stone. Rowan built a fire with hands that didn’t fumble, roasted rabbit over the flame, and handed her a piece without ceremony. “Eat,” he said, as if hunger were not a question but a fact.

Lila ate fast, starved in more ways than one. The fire warmed her cheeks, but it didn’t thaw the knot in her chest. Rowan watched the cave mouth more than he watched her, listening to the wind like it carried messages only he could read.

“You’re wondering how I know,” he said at last, voice steady. “When Bart Vane cocked his pistol, your ear twitched. Fear makes people listen, even when they’re pretending not to.”

Lila’s fingers tightened around the meat. Even in the firelight, she kept her face blank. Habit was a chain, and hers had been forged carefully.

“I don’t care why you pretend,” Rowan continued, not unkind, just blunt. “But on this mountain, if you don’t listen, you die.” He turned his back to her and lay down as if trust were something you could choose by necessity.

The next day, they reached his cabin, built into a cliff like an eagle’s nest, half-hidden by pines and rock. It was not the lair of a savage. Inside were shelves of books, weapons cleaned and ordered, herbs hung to dry, and a table scrubbed smooth. The place held the disciplined quiet of someone who had once believed in rules, even if the world had stopped believing in him.

Rowan set down his pack and nodded toward a broom. “This is it,” he said. “I hunt. You cook. We both work.”

Lila swallowed, her throat raw with unsaid words. The arrangement sounded simple, but nothing in her life had ever been simple. Still, the cabin felt safer than the town. Safer than Amos. Safer than Bart Vane’s hands.

She took a risk so small it felt enormous. “Why?” she whispered, voice thin from disuse.

Rowan froze. Slowly, he turned, and for the first time his expression shifted, something like pain flickering behind his eyes. “Because I know who your father is,” he said. “And I know who Bart Vane works for.”

Lila’s knees threatened to fold. “Kessler,” she breathed, the name tasting like dust.

Rowan nodded once. “Gideon Kessler’s been looking for something that went missing the night your mother died. He thinks you have it.”

The truth hit her like a door slamming. The ledger. The black book her mother had hidden under a loose floorboard, the one Amos had never found because he was always too drunk to look carefully. Lila had kept it not because she understood it, but because her mother’s hands had been shaking when she pushed it into Lila’s arms and mouthed one word with terrified urgency: proof.

Lila nodded, because denial would have been pointless in a cabin this small, with a man this perceptive.

Rowan closed his eyes as if hearing a verdict. “Then the war isn’t over,” he murmured. “It’s just coming up the mountain.”

Outside, the storm sealed the pass like a prison door. And somewhere below, men were already being paid to climb.

Weeks passed, snow piling higher than the cabin windows until the world became nothing but white glare and howling wind. The mountain turned into its own silent kingdom, and inside that kingdom something else began to shift. Lila’s silence, which had once been a wall, started to crack under the steady pressure of survival. Rowan did not treat her like a rescued woman, nor did he treat her like a fragile thing to be handled with careful sympathy. He treated her like someone who had to live, and living required effort.

At dawn each morning, he woke her, pressed tools into her hands, and put her body to work until her mind stopped wandering into old nightmares. She learned to split wood until her palms bled, to haul water from a spring even when ice formed in her hair, to skin animals without wasting meat because waste was a luxury the mountain didn’t allow. Rowan spoke plainly, never gently, never cruelly, just honest in the way of men who had run out of patience for lies.

“Fear freezes people,” he told her one night when she stared too long into the fire. “Work keeps them alive.”

At night they sat by the flames, the cabin creaking as the wind battered it, but the warmth held. It was during one of those nights, when the air felt almost peaceful, that Lila finally pried up the loose floorboard near the hearth and pulled out the black ledger. The leather cover was cracked and dark, stained with something that looked too much like old blood. Her hands shook as she set it on the table, because touching it felt like touching the night her mother died.

Rowan stopped sharpening his knife when he saw it.

“Read,” he said, and his voice was different, tightened by something personal.

Lila’s throat felt too small for words, but she forced them through. Her voice wavered at first, rusty and thin, but as she read names and dates and payments, it steadied. Sheriff Harland Pike. Bart Vane. Gideon Kessler. Bribes, stolen land claims, disappearances written like arithmetic. Each line proved what the town pretended not to know: Copper Ridge wasn’t rough by accident, it was engineered by men who profited from lawlessness.

When Lila reached an entry marked with a single fifty-dollar payment and a name beneath it, Rowan’s hands stilled completely.

“Read that again,” he said.

Lila’s eyes blurred, but she read it, slower this time, as if the words might change if spoken carefully. The name was Rowan’s brother, Thomas Cade, and beside it a note that made Lila’s stomach twist: Paid for silence. Problem removed.

Rowan stared at the fire like it had turned into a grave. “That was my brother,” he said, each word carved out of something deep. “They said he ran off. They said he took money and vanished. I knew better. I just never had proof.”

The fire popped loudly, breaking the moment, and Lila realized with a sudden heaviness that this was no longer only about her survival. Rowan had dragged her up this mountain not just to save her from Bart Vane’s hands, but because the truth she carried was the knife he had been missing. And now the truth had teeth.

From that night on, the training changed.

Rowan taught her to shoot. The rifle bruised her shoulder at first, and her shots went wide. When tears filled her eyes, Rowan’s voice snapped, not in anger, but in urgency. “Tears blur sight. Blurred sight gets you killed.”

Lila grit her teeth and tried again. Every missed shot became a lesson, every bruise a reminder that pain was temporary but death was permanent. By January, she could hit a playing card nailed to a stump from fifty yards. By February, she could load, clean, and fire in the dark with hands that no longer trembled. But it wasn’t only weapons. Rowan taught her how to listen, how to hear when the forest went quiet, how to smell smoke before seeing it, how to feel danger before it arrived.

“You survived by pretending to be deaf,” Rowan told her as winter began to loosen its grip. “Now you survive by hearing everything.”

The mountain seemed to sense the coming storm of men. Birds vanished. The woods grew still. Rowan slept in short shifts, rifle always close, as if rest was a privilege he no longer trusted. Then one morning, the danger arrived with the sharp punctuation of gunfire.

Lila was alone on the porch, turning butter with stiff fingers, when the forest went silent so suddenly it felt like the world had stopped breathing. She remembered Rowan’s lesson: silence meant death. Her hand moved toward the rifle propped by the door just as a bullet shattered the porch post inches from her head. Wood splintered, and instinct shoved her body down and inside.

Glass exploded as another shot tore through the window. Two men advanced from the trees, half-hidden by brush, rifles raised.

“Come out, girl!” one shouted. “Mr. Vane wants a word!”

Her hands shook, but her mind stayed clear, because fear no longer had the whole of her. She fired through the shattered window. One man went down screaming, clutching his leg. The second opened fire, bullets ripping through the cabin walls, punching holes that sprayed splinters like angry insects.

Then the mountain roared.

Rowan’s buffalo gun thundered from above, a sound so deep it felt like the cliff itself had spoken. The second man dropped instantly, collapsing into snow like a puppet whose strings had been cut.

Rowan slammed into the cabin moments later, breath hard, eyes scanning. When he saw Lila alive, something in his face twisted, panic cracking through his usual control. He grabbed her shoulders, held her too tight, then seemed to realize what he was doing and stepped back as if touch were dangerous.

“You did good,” he said, voice rough. “You lived.”

Outside, Rowan ended the wounded man’s suffering swiftly, not out of cruelty, but out of necessity. From the dead man’s coat he pulled a crumpled note, a crude wanted notice: Payment upon delivery of the girl alive.

Rowan’s jaw tightened. “They’ve made you worth a bounty,” he said. “Which means they’re done playing.”

Lila’s chest tightened, not with fear of strangers, but with the sudden memory of Amos’s laughter. “My father,” she whispered, surprising herself with how little tenderness remained in the word.

Rowan’s eyes flicked to her. “He’s part of it,” he said, then softened the edges just enough to be truthful instead of cruel. “But he’s also leverage to them. Men like Kessler don’t keep loose ends. They keep tools.”

That night, as wind clawed at the cabin, Rowan made a decision that changed the shape of their lives. Hiding had kept them alive, but it had also trapped them on the mountain with a target on Lila’s back. If they wanted this to end, they needed law, or at least the closest thing the territory had to it.

“We go down,” Rowan said, tapping the ledger. “We take this to a U.S. Marshal. But first, we draw them out where we can see them.”

Lila’s mouth went dry. “Copper Ridge.”

Rowan nodded once. “You’ll be bait.”

A month ago, Lila would have broken at the idea. Now she felt fear wrap around her ribs, but beneath it something steadier stood up. She was done being a ghost. She was done being sold. If the world wanted her silent, she would make it listen.

“I’ll do it,” she said, and the words tasted like steel.

Copper Ridge looked worse than she remembered, as if the months had rotted it further. Mud and smoke filled the streets. Men leaned in doorways like vultures waiting for something to die. Lila rode in alone at midnight, shoulders hunched, eyes down, playing the silent ghost again, because sometimes armor was still useful. Rowan stayed out of sight, high on a rooftop with his rifle, moving like a shadow the town couldn’t buy.

Bart Vane saw her immediately, because men like him always noticed what they believed they owned. He stepped out of the saloon with a grin like a knife. “Well, look what crawled back,” he sneered, grabbing her chin. “You bring the book?”

Lila widened her eyes and pretended confusion, pointing clumsily at her saddlebags as if she didn’t understand words. Bart laughed, pleased by what he thought was proof of her helplessness. He yanked her toward the livery stable, barking orders to his men, and that was when the night exploded.

Dynamite tore through the stable wall, fire lighting the sky with a sudden violence that made horses scream. Men scattered, shouting, some firing blindly into smoke. The shock ripped Bart’s attention away for one heartbeat, and in that heartbeat Lila cut the saddle strap with the knife Rowan had given her. The bags hit the ground hard, spilling nothing important, because the ledger was hidden under her coat, pressed against her ribs like a second heart.

Rowan fired from the roof, shots clean and deliberate, taking down the men who aimed for Lila first. Then he dropped from the rooftop like a falling bear, hitting the mud with a force that knocked breath from the nearest man. He moved with brutal efficiency, not rage-flailing, but purposeful, as if every motion had been planned in the quiet of winter nights.

He took Bart alive.

Lila ran to the jail, heart hammering, because she knew exactly where her father would be if Kessler’s men wanted leverage. The sheriff’s office stank of stale coffee and corruption. Inside a cell, Amos sat broken and bleeding, his face swollen, his eyes finally sober enough to see what he’d done.

Lila stared at him through the bars, and for a moment she felt the old urge to vanish into silence, to make herself small. Then she remembered her mother’s last look, and the ledger’s weight, and Rowan’s whisper.

Amos croaked, “Lila… I didn’t… I had to…”

“You didn’t have to,” Lila said, voice steady. The sound of her own words seemed to shock him more than any fist could. “You chose to.”

Rowan appeared behind her, keys in hand taken from a man who no longer needed them. He unlocked the cell, and Amos stumbled out, trembling. For a second, Lila thought her father might reach for her, might try to reclaim her as if he still had rights. Instead he collapsed to his knees in the mud outside, sobbing with the raw, animal shame of a man who had spent years drinking to avoid his own reflection.

They fled Copper Ridge under gunfire, dragging Bart Vane behind them as insurance. By dawn, smoke rose behind the town, and the chase began.

For days they climbed through rough country, abandoning horses where trails grew too narrow, moving through snow and stone with the exhaustion of people who had stopped hoping for mercy. Bart limped, hands tied, his arrogance bleeding out of him mile by mile. Amos grew quieter, shame weighing him down heavier than his injuries. More than once Lila caught him looking at her as if he were trying to recognize the girl he’d sold and failing, because she no longer fit the shape of his cruelty.

When hired killers waited for them at High Knife Pass, Rowan made a brutal choice. He shoved Bart forward first, using the man’s own fear as a shield. Bart screamed, stumbling, and the ambushers fired on instinct, bullets punching into the body they recognized. In that instant, Rowan and Lila returned fire with the calm coordination winter had taught them. One man fell. Another tumbled down the slope when Rowan tackled him, Bart’s rope snarling them together like fate refusing to separate guilt from consequence.

When the smoke cleared, the path was open, but the cost was written in blood and shaking hands. Lila stood over the pass, breathing hard, listening to the wind whistle through rock. It sounded like the world exhaling.

The final stretch to Fort Laramie felt longer than the mountain ever had, because the land opened wide, flat, exposed, offering nowhere to hide. Dust replaced snow. The sun beat down on cracked skin. They traveled mostly at night, avoiding roads and towns, watching the horizon for riders that never seemed far behind.

When they reached the fort at noon on the eleventh day, soldiers and townsfolk stopped to stare: a mountain man in furs, a scarred foreman bound with rope and bleeding, a thin woman with a rifle and eyes sharpened by survival, and a drunk father limping in shame. They walked straight to the U.S. Marshal’s office without slowing, because hesitation was how men like Kessler won.

Marshal Elias Whitaker listened in silence as Rowan placed the ledger on his desk. The marshal’s face was weathered, his eyes old with the knowledge that law in the territory often arrived too late. He read slowly, jaw tightening with every page, every name, every payment that turned crimes into bookkeeping. When he looked up, his gaze moved from Bart to Amos to Lila, and something in his expression shifted from skepticism to grim certainty.

“This book can hang Gideon Kessler,” Whitaker said quietly.

Bart Vane, smelling the rope that awaited him, started talking before anyone even asked. He testified to save his neck, and it earned him a cell instead of a noose. Amos testified too, voice breaking as he confessed, not trying to excuse himself, only trying to name the truth out loud as if naming it might finally punish him properly. The judge gave Amos one year of hard labor, not mercy, not cruelty, but consequence. When the gavel fell, Lila felt a weight lift from her chest so suddenly she swayed, as if she’d been carrying a boulder so long she’d forgotten it was there.

Outside, spring sunlight warmed her face, and for the first time in years she realized she was not bracing for a blow.

Rowan stood beside her, hands tucked into his coat, gaze already drifting toward the distant line of hills. He looked like a man who had completed a task, not like a man who believed he deserved a future.

“It’s done,” Lila said, and her voice held both relief and dread.

Rowan nodded. “For you, maybe.”

“For you too,” she insisted, stepping closer. “Your brother.”

Rowan’s throat worked as if swallowing something bitter. “It don’t bring him back,” he said. “And it don’t fix what the war did to me.”

Lila studied him, and in that moment she understood something she hadn’t on the mountain. Rowan had saved her not because he was a saint, but because he knew what it meant to be trapped under someone else’s cruelty, and he couldn’t bear watching it happen again. He had pulled her out of the saloon, but the mountain had pulled both of them out of the roles the world assigned: victim, monster, ghost, weapon. And now the world wanted them to return neatly to those boxes.

She looked away for a second, just long enough to choose her words carefully. “I don’t want to be free alone,” she said.

Rowan’s eyes flicked to her, guarded. “You don’t owe me anything.”

“I’m not paying a debt,” Lila replied. “I’m telling the truth.”

The next morning, she woke to find Rowan gone.

Panic hit her hard, sharp as winter air. She ran to the livery stable, and her fear was confirmed by small evidence: Rowan’s mule missing, his trail already fading toward the foothills. He was leaving the way wounded men often did, quietly, before anyone could ask them to stay.

Lila didn’t hesitate. She saddled a horse, rode hard, and found him at the edge of the rising hills, moving alone toward the mountains as if the world behind him had already ceased to exist.

Rowan turned when he heard her approach, because he always heard.

“Go back,” he said, and there was no anger in it, only weary certainty. “You’re free now. You can have a life.”

Lila reined in beside him, dust rising around their horses. “What life?” she asked. “The kind where people look at me and only see what they almost did to me?”

Rowan’s jaw tightened. “You can build something. In town. With people.”

“People sold me for whiskey,” Lila said, not loudly, but with a clarity that cut. Then she softened, because she wasn’t speaking to Copper Ridge anymore. She was speaking to Rowan. “You told me my silence was armor. You gave me a new kind of hearing. You taught me to live. And now you want to leave like none of it mattered.”

Rowan’s eyes darkened, and for a moment he looked like a man fighting a bear he couldn’t shoot. “I’m broken,” he said, voice low. “The mountains are all I know.”

Lila nodded slowly. “I was broken too,” she said. “Or at least that’s what they wanted. But I’m standing here, aren’t I?”

Silence stretched between them, full of all the things they didn’t know how to say. Then Lila reached out and took his hand, and the simple contact felt like choosing a future instead of surviving a past.

“I love you,” she said, voice steady, because she had learned that words could be weapons, but they could also be bridges. “Not because you saved me. Because you saw me. And you didn’t turn away.”

Rowan stared at their joined hands as if he didn’t trust what he saw. When he finally looked up, his eyes were wet, not with weakness, but with the exhaustion of a man who had been alone too long.

“You don’t know what you’re asking for,” he whispered.

“I do,” Lila answered. “I’m asking for the same thing you gave me. A choice.”

The wind moved through the grass, carrying the distant sound of the fort behind them, the faint noise of civilization with all its rules and cruelty and comfort. Rowan breathed in, then out, like a man stepping out of a cage he’d built himself.

“Then we go,” he said.

Not away from justice, not away from life, but toward something quieter, something earned. They turned their horses toward the high peaks together, and for the first time Lila didn’t feel like a ghost riding behind someone else’s will. She rode beside Rowan, listening to the world with ears that had never been broken, only hidden.

Copper Ridge never saw them again. But some said that if you walked the razorback ridges at dawn, you might see smoke rising from a hidden cabin tucked into the cliffs like a secret kept gently. A man and a woman living where the world couldn’t reach them, not because they were afraid, but because they had learned the difference between silence that cages you and silence that finally lets you breathe.

And if you listened closely, you might hear it: not the absence of sound, but the presence of peace.

THE END

News

All Doctors Gave Up… Billionaire Declared DEAD—Until Poor Maid’s Toddler Slept On Him Overnight

The private wing of St. Gabriel Medical Center had its own kind of silence, the expensive kind, padded and perfumed…

Mafia Boss Arrived Home Unannounced And Saw The Maid With His Triplets — What He Saw Froze Him

Vincent Moretti didn’t announce his return because men like him never did. In his world, surprises kept you breathing. Schedules…

Poor Waitress Shielded An Old Man From Gunmen – Next Day, Mafia Boss Sends 4 Guards To Her Cafe

The gun hovered so close to her chest that she could see the tiny scratch on the barrel, the place…

Her Therapist Calls The Mafia Boss — She Didn’t Trip Someone Smashed Her Ankle

Clara Wynn pressed her palm to the corridor’s paneled wall, not because she needed the support, but because she needed…

Unaware Her Father Was A Secret Trillionaire Who Bought His Company, Husband Signs Divorce Papers On

The divorce papers landed on the blanket like an insult dressed in linen. Not tossed, not dropped, not even hurried,…

She Got in the Wrong Car on Christmas Eve, Mafia Boss Locked the Doors and said ‘You’re Not Leaving”

Emma Hart got into the wrong car at 11:47 p.m. on Christmas Eve with a dead phone, a discount dress,…

End of content

No more pages to load