Silverton, Colorado Territory, 1877, did not wake gently. It woke like a struck match, all at once, with smoke and shouting and the metallic cough of the stamp mills already chewing rock somewhere up the valley. The sky was still bluish-black when lanterns began to sway along Blair Street, and the wooden buildings, so proud from a distance, looked up close like they were holding themselves together by stubbornness and nails. Men with coal-streaked faces shuffled toward the mines, boots heavy, shoulders heavier. Women moved too, quieter, carrying buckets, laundry baskets, and the kind of tired that clung to the bones. In that thin hour before sunrise, the town belonged to whoever had not slept, and to whoever could not afford to.

The Gem Theater and Saloon sat like a bright bruise at the center of it, lit up and loud even when the rest of Silverton pretended at righteousness. Music leaked out through the cracks, a piano with a broken tooth somewhere in the melody, and laughter that sounded a little too sharp to be honest. Inside, the air was thick with cigar smoke and spilled whiskey, and the tables were crowded with men trying to turn luck into rent, or rent into more luck. At one table, near the back where the lamp smoked and the boards creaked, Elias Mercer sat with his hat pushed back and his eyes glazed by drink he could not pay for. His hands were not the hands of a miner anymore. They had been once, callused and sure, but now they trembled, a pale kind of shaking that came from a man losing arguments with himself.

“Elias,” someone muttered, not kindly, “you’re down to air and prayers.”

Across from him, Hiram Blackwell spread his cards with the slow satisfaction of a man who liked his victories to be witnessed. Blackwell wore a clean vest in a town that ate clean clothes like a fire, and his boots were polished enough to catch the lamplight. He wasn’t a miner, not really. He was what the mines attracted once they began to pay: the middlemen. The suppliers. The men who spoke of “labor” as if it were a tool you stored in barrels. He had a small ledger book at his elbow, as natural to him as a revolver to other men, and his smile had the cold patience of someone who could wait all day for a desperate person to make a mistake.

Elias licked his lips. “One more hand.”

Blackwell’s eyebrow lifted. “With what?”

Elias fumbled in his pockets, producing a few coins, then nothing, then the embarrassment of empty cloth. He stared at his hands, as if he might squeeze money out of his palms if he hated himself hard enough. The men around them leaned in, not to help, but because misery was the cheapest entertainment in town.

“Debt,” Blackwell said softly, and the word landed like a stone.

Elias’s throat worked. “I’ll… I’ll work it off.”

“You’ll die trying,” Blackwell replied, still gentle, still smiling. “And I don’t run a charity.”

Elias blinked, slow. “Then what do you want?”

Blackwell’s eyes flicked, not toward Elias, but past him, into the idea of Elias’s life, into the thin house on the edge of town where a woman used to live before she got buried in a hillside cemetery, into the two girls who still breathed. “I want what you can pay with.”

A hush formed, not because anyone was shocked, but because everyone understood too well what kind of town they lived in. Elias’s mouth opened, closed, opened again. “You don’t mean—”

“I mean your youngest,” Blackwell said, as if he were discussing a mule. “The little one. The one with the dark braid. Lily.”

Elias jerked like he’d been slapped, but his eyes didn’t sharpen with a father’s rage. They sharpened with a gambler’s arithmetic. A debt on one side. A child on the other. And the terrible thing about arithmetic was that it didn’t care what was sacred.

Blackwell set a sheet of paper on the table, already prepared. “I’m a lawful man,” he said, and the men who knew him snorted into their drinks. “I keep contracts. Makes everything clean. You sign, I clear your debt with the Gem, and the girl’s mine to place.”

“Place,” Elias echoed, too drunk to hear the cruelty hiding in a polite word.

“Mining camps need sorters,” Blackwell continued, voice low and almost reasonable. “Kids have small hands. They pull ore, pick through tailings, work the chutes. It’s not killing work.”

Somewhere, the piano hit a wrong note and kept going anyway. Elias stared at the pen, as if it were a snake. Then he laughed once, jagged and sick. “She’s… she’s just a child.”

Blackwell’s smile never moved. “So is your debt, compared to what it will grow into if you keep feeding it. Three months from now you’ll be begging to sell both girls. Today I’m offering mercy.”

The word mercy, in that room, tasted like rot. Elias’s hand hovered over the pen. Around them, the table seemed to tip, as if the whole saloon leaned toward the moment. Blackwell watched with the calm interest of a man who owned time. Elias took the pen. His fingers shook. He scrawled his name like a man signing his own sentence, and in the crooked, drunken strokes, he pushed Lily Mercer out of childhood and into the gears of a machine that did not care if she lived.

When Elias stumbled out into the dawn, the cold hit him hard enough to make him cough, but it wasn’t cold that finally sobered him. It was the quiet. It was the thought of a small bed with a patchwork quilt, and the weight of a braid against a pillow. For a moment, he stood in the street, swaying, and it looked like the man he used to be might rise up inside him and scream. But then he swallowed, the way he always swallowed, and he turned toward home with the numb obedience of someone who had already decided he did not deserve redemption.

By the time Clara Mercer arrived at the laundry house where she worked, the sun had climbed, turning the snow on the peaks into a blinding promise of beauty Silverton never kept. Clara was fifteen, tall for her age, shoulders squared by hauling water and wringing sheets until her wrists ached. Her hair was pinned back in a practical knot, and her hands were raw at the knuckles. She moved like someone who had learned early that softness was expensive. The laundry smelled of lye and steam and exhaustion, and Clara’s boss, Mrs. Danner, handed her a basket without looking up.

“Those go to the hotel,” Mrs. Danner said. “And if you’re late again, girl, I’ll find another set of hands.”

Clara didn’t answer. She had learned that silence sometimes kept you employed longer than pride. She worked through the morning, scrubbing collars and cuffs stained with men’s sweat and women’s powder, watching the steam rise like ghosts. All the while, something in her chest kept tapping, a faint nervous rhythm, because Lily had been clingy lately, and Clara had promised her she’d be home before dark, and promises were the only currency Clara trusted.

She left as soon as the last basket was delivered, coins heavy in her pocket, not enough to change a life but enough to buy beans and flour. The walk home took her past the Gem, and she glanced at the swinging doors with a familiar, bitter resignation. Elias had been in there last night. Elias was always in there, unless he was passed out somewhere too ashamed to come home. Clara’s jaw tightened, and she kept moving, telling herself, as she often did, that she only needed to make it to sixteen, to seventeen, to some age where she could take Lily and leave this town like shedding a skin.

The house was quiet when she entered, quieter than it should have been. The stove was cold. The blanket on Lily’s bed was folded too neatly. Elias sat at the table with his hands clasped as if he were praying, but there was no prayer in him, only dread.

“Where is she?” Clara asked, and even before the words finished leaving her mouth, the air answered with a thick, ugly certainty.

Elias’s eyes didn’t meet hers. “Clara—”

“Where. Is. Lily.”

He flinched at her tone, and for a heartbeat, Clara saw the flicker of shame that meant he understood. Then he spoke, and his voice was hoarse, like the words scraped his throat on the way out.

“I had… a debt,” he said.

Clara stared at him. “A debt.”

“At the Gem,” he whispered, as if naming the place would summon its demons. “Blackwell offered… a way out.”

Clara’s hands went cold. “What did you do.”

Elias swallowed hard. “I signed.”

Clara felt the world slow, not dramatically, but in the way a body does right before it’s hit. “Signed what.”

“A contract,” Elias said, and his eyes finally lifted, and they were wet in a way that almost looked like humanity. “He… he takes her. For work. Just for a while. Until it’s paid.”

Clara’s breath stopped. She didn’t scream. She didn’t throw anything. Something in her simply clicked into place, like a lock turning. Because rage was hot, and heat burned out. Clara needed something that wouldn’t burn out.

“How long,” she asked, voice oddly calm, “until he comes to collect?”

Elias blinked. “He said… by noon.”

Clara looked at the window. Sunlight cut across the floor in a bright stripe, mocking her with its ordinary beauty. She measured the distance between now and noon like a person measuring the edge of a cliff.

“That’s three hours,” she said, not to Elias, but to herself.

Elias’s shoulders sagged. “Clara, I—”

She held up a hand. “Don’t,” she said, and for the first time, her voice trembled. “If you say you’re sorry, I might waste time believing you.”

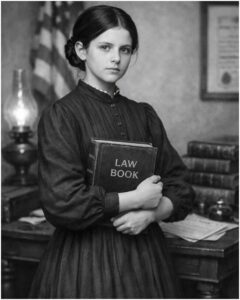

Elias stared at her as if he wanted to argue, to insist he still mattered. Clara turned away from him, and her gaze snagged on the shelf by the wall where a few old books sat, their spines cracked from neglect. They were her mother’s, mostly hymns and a Bible. But one book, thick and brown, had belonged to her grandfather, a man who’d once tried to be a lawyer back east before the West swallowed him. Clara had found it two years ago and read it in secret by candlelight, not because she dreamed of courtrooms, but because words were the only weapons she had ever been offered.

She walked to the shelf. Pulled the book free. Dust rose in a little cloud, like the past exhaling. The title was faded, but she knew it: Territorial Statutes and Federal Ordinances. She had traced those pages so often she could almost smell the ink.

Elias watched her, confused. “What are you doing?”

Clara turned, book in her hands like a shield. “I’m going to bring Lily home.”

He barked a sad laugh. “How? With what? You think Blackwell cares about paper?”

Clara’s eyes sharpened. “He cared enough to make you sign one.”

Elias opened his mouth, but Clara was already moving. She grabbed her coat, shoved the book under her arm, and paused only long enough to look at him one last time. In that look was everything she couldn’t afford to say aloud: you have failed us, you have sold us, you are no longer my father except by biology.

“If you try to stop me,” she said quietly, “you’ll lose both daughters today.”

She stepped into the street, and the cold slapped her awake. Her boots hit the boards of the sidewalk hard, her breath white in the air. The town around her bustled with its usual cruelty, unaware that one girl’s life had been turned into a bargaining chip. Clara did not pray. Prayer was for people who had time to wait for mercy. Clara had three hours, and she intended to manufacture justice with her own hands.

The courthouse sat at the edge of town, a squat building pretending at authority. It was barely more than a room with a judge’s chair, but in a place like Silverton, even a pretense could become power if enough people believed in it. Clara pushed through the door, and the warmth inside smelled like ink and damp wool. A clerk looked up, startled to see a girl storming in like she owned the place.

“Miss,” he began, tone already irritated, “court isn’t—”

“I need the federal judge,” Clara cut in.

The clerk blinked. “Judge Hart isn’t hearing petitions this morning.”

Clara placed the statute book on the counter with a thud that made the ink bottles tremble. “Then you need to wake him.”

The clerk’s mouth tightened. “Who are you?”

“Clara Mercer,” she said. “And my sister has been sold into debt bondage.”

The words hung there, heavier than the air. The clerk’s eyes flicked over her, taking in her plain coat, her chapped hands, the exhaustion that made her look older than fifteen. He looked unconvinced, because the West had taught people to doubt everything, especially the truth.

“That’s a serious accusation,” he said. “Do you have proof?”

Clara reached into her pocket and pulled out the copy of the contract Elias had left on the table, maybe out of guilt, maybe because even he knew what he had done was monstrous. She slid it across. “He’s coming at noon,” she said. “So you can doubt me later. Right now you can either help, or you can watch a child disappear into the mines.”

The clerk took the paper reluctantly, eyes narrowing as he read. His expression shifted, not into kindness, but into something like alarm. Because the contract was written in careful language, and careful language meant its author knew exactly what sins he was committing.

“This… this is signed,” the clerk murmured.

“Yes,” Clara said. “By a man who was intoxicated, who cannot legally consent under territorial statute regarding competency. And even if he were sober, the contract violates the ordinance forbidding the binding of minors to labor to satisfy parental debt.”

The clerk looked up sharply. “How do you know that?”

Clara’s fingers tightened on the book. “Because I read,” she said. “And because I have been afraid for years that my father would trade our lives for his vices.”

The clerk’s gaze softened a fraction, the smallest crack in his skepticism. Still, he hesitated, because people like him were trained to fear overstepping. Clara leaned forward, voice low, urgent.

“Judge Hart made a speech two weeks ago,” she said. “At the church. About children not being owned by anyone. If he meant it, he’ll sign an injunction. If he didn’t mean it… then say so now, and I’ll run to the mine camp myself and drag her out with my bare hands.”

The clerk stared at her, and something in her steadiness seemed to convince him. He stood, pushed back his chair. “Wait here,” he said, and his tone had changed. It wasn’t warm, but it was no longer dismissive. It was the tone of a man who has accepted that something important is happening whether he’s comfortable or not.

Clara waited, pacing, counting minutes like rosary beads. Through the thin walls, she could hear hurried footsteps, a door opening, a muffled voice. Then another. The building seemed to hold its breath.

Judge Nathaniel Hart entered ten minutes later, still buttoning his coat, hair rumpled from sleep. He was younger than Clara expected, with tired eyes and a mouth set in a line that suggested he had seen too many compromises dressed up as law. He took the contract from the clerk, read it once, then read it again, slower. When he looked at Clara, his gaze was sharp, not unkind.

“You’re Clara Mercer,” he said.

“Yes, sir.”

“Fifteen.”

“Yes, sir.”

“And you understand what you’re alleging,” he said. “That a labor contractor has purchased your sister as payment for a gambling debt.”

Clara swallowed. “Yes, sir.”

Judge Hart’s eyes flicked to the statute book on the counter. “And you came armed,” he noted, almost dryly.

Clara’s cheeks burned. “I came prepared,” she said, because pride was dangerous, but clarity was not.

He studied her for a long moment, then asked, “Where is your sister now?”

“At home,” Clara said. “He hasn’t taken her yet. He’s coming at noon.”

Judge Hart exhaled slowly, as if the whole town’s ugliness sat on his ribs. “Your father signed this?”

“Yes,” Clara said. “Drunk.”

“And you believe Blackwell will abide by an order?”

Clara met his eyes. “He believes in paper when it serves him,” she said. “So make it serve us.”

The judge’s mouth twitched, not quite a smile, but something like approval. He turned to the clerk. “Prepare an emergency injunction,” he said. “Federal seal. Immediate effect. Deliverable on sight.”

The clerk hesitated. “Your Honor, the territorial court—”

“The territorial court can argue with me after the child is safe,” Judge Hart snapped, and his voice had steel now. He looked back at Clara. “If Blackwell defies this order, he will be charged with attempted trafficking of a minor under federal jurisdiction. Do you understand?”

Clara’s throat tightened. “Yes,” she whispered.

“And your father,” Judge Hart continued, voice lowering, “may lose more than his pride today.”

Clara’s hands shook, but she held them steady against the counter. “He already lost it,” she said. “He just hasn’t admitted it.”

When the clerk handed her the injunction, the paper felt heavier than paper should, as if the seal had weight. Clara tucked it inside her coat like a beating heart and ran.

The streets blurred as she sprinted, skirts snagging wind, lungs burning in the cold. She didn’t notice the stares, the muttered comments, the way men paused to watch a girl run like the devil was behind her. In a way, he was. Desperation was a devil with many faces, and one of those faces wore a clean vest and carried a ledger.

She reached home with minutes to spare. Inside, Lily sat on the floor with a rag doll, humming softly, unaware that her childhood had been traded like a coin. Her eyes brightened when she saw Clara.

“Clara!” Lily chirped. “You’re early!”

Clara crossed the room in two strides and knelt, grabbing Lily’s small hands. They were warm. Alive. The fact of them almost broke her. She swallowed hard and forced a smile that felt like it might crack.

“Listen to me, bird,” Clara said, using the nickname she’d given Lily when their mother died and Lily cried for days. “You stay close to me today, alright?”

Lily frowned. “Why?”

Clara brushed hair from Lily’s face. “Because I need you,” she said, and it was the truth, stripped down to its bones.

A knock hit the door like a gunshot. Clara’s spine went rigid. Elias flinched in his chair like a man waiting to be hanged. Lily looked toward the door, curious.

Clara stood, smoothing her coat. She pulled the injunction from inside it, fingers tight. “Stay behind me,” she murmured to Lily, and Lily, sensing the change in the air, obeyed without argument.

Clara opened the door.

Hiram Blackwell stood there, hat tipped politely, as if he were a neighbor come for sugar. Two men lingered behind him, heavy-shouldered, the kind of men hired to make “transactions” go smoothly. Blackwell’s eyes slid past Clara, searching.

“Miss Mercer,” he said, voice syrupy. “I’m here for the girl.”

Clara held up the paper, and the federal seal caught the light like a warning. “You’re here for nothing,” she said.

Blackwell’s smile twitched. He took a step closer, squinting at the document. “What’s this?”

“An injunction,” Clara replied. “Signed by Judge Hart. It voids your contract until a hearing.”

Blackwell’s gaze sharpened, and for the first time, his civility cracked enough to reveal something ugly underneath. He snatched the paper from her hand, scanning it fast. His jaw worked. For a moment, Clara thought he might tear it in half. But he didn’t. He held it like a thing that burned.

“You ran to court,” he said, incredulous, almost amused. “You.”

Clara met his eyes. “Yes,” she said. “Me.”

Blackwell laughed once, harsh. “You think paper stops men like me?”

Clara leaned in, voice low. “Paper stops men like you because men like you use paper to pretend you’re lawful,” she said. “And if you ignore it, you stop pretending. Then you’re just a kidnapper in a clean vest.”

Behind her, Lily clutched Clara’s skirt. Blackwell’s eyes flicked to the small hand, and something like frustration flashed across his face. He liked easy prey. He liked silence. He did not like complications.

“This isn’t over,” he said, handing the injunction back with a snap.

Clara took it. “No,” she agreed. “It isn’t. But you’re not taking her today.”

Blackwell’s nostrils flared. He stepped back, adjusting his hat. The men behind him shifted, restless, but Blackwell lifted a hand, and they stilled. He glanced at Elias, still sitting at the table like a ruined statue.

“You,” Blackwell said to Elias, voice dripping contempt. “You couldn’t even sell your own child properly.”

Elias’s face crumpled, and for a split second, Clara almost saw pity in herself. Then she remembered Lily’s bed, empty, and pity died quietly.

Blackwell turned and walked away, boots striking the boards like punctuation. The moment he was out of sight, Clara’s knees weakened. She shut the door and leaned against it, chest heaving. Lily pressed her face into Clara’s coat.

“Clara,” Lily whispered. “What’s happening?”

Clara closed her eyes. Her voice came out rough. “Grown-up problems,” she said. “But you’re safe.”

Elias made a sound that might have been a sob. Clara didn’t look at him. Not yet. Because the next battle wasn’t at the door. It was in the courtroom, where words decided whose life mattered.

That afternoon, the courthouse was crowded in the way only scandal could summon. Men who never attended church came to witness judgment. Women who rarely left their porches stood in the back, eyes sharp, because even in a harsh town, the idea of a child being claimed like property hit a nerve people pretended they didn’t have. Blackwell stood at the front with his lawyer, a thin man with a mustache like a line drawn by an angry pencil. Elias sat hunched behind Clara and Lily, looking smaller than Clara had ever seen him. Lily’s feet didn’t touch the floor from the bench, and she swung them gently, unaware she was the center of a legal storm.

Judge Hart entered, and the room quieted like a held breath. He looked older now, not because hours had passed, but because responsibility aged a person faster than time.

Blackwell’s lawyer began smoothly. “Your Honor, this was a lawful contract—”

Judge Hart held up a hand. “I’ve read it,” he said. “Do not insult this court by calling it lawful.”

The lawyer blinked. “Sir, the father—”

“The father,” Judge Hart cut in, eyes cutting to Elias, “was intoxicated and indebted. You exploited both.”

Blackwell’s lawyer straightened. “There is no statute explicitly forbidding a parent from—”

Clara stood before she realized she was moving. “There is,” she said, voice ringing sharper than she expected. Every head turned toward her. The clerk looked nervous. Judge Hart looked… interested.

“Identify yourself,” Judge Hart said.

“Clara Mercer,” she replied. “Sister of Lily Mercer.”

Judge Hart nodded once. “Proceed,” he said, and with that single word, he handed her the room.

Clara’s fingers trembled as she opened the statute book she’d carried like scripture. “Territorial ordinance regarding bonded labor,” she said, reading carefully. “It forbids binding minors to service to satisfy the debt of another. It defines such service as involuntary if the minor cannot consent freely.”

Blackwell’s lawyer scoffed. “She’s a child. Her understanding is irrelevant.”

Clara lifted her gaze. “Exactly,” she said. “That’s why she cannot be sold.”

A murmur swept the crowd, the kind of sound that meant the town had found its conscience for one afternoon. Judge Hart leaned back, steepling his fingers.

Blackwell himself finally spoke, voice sharp with annoyance. “Your Honor, I offer work. Food. Shelter. Many children in this territory would be grateful.”

Judge Hart’s eyes hardened. “Children should not be grateful for being exploited,” he said. “They should be protected from needing gratitude for crumbs.”

Blackwell’s face reddened. “You’re making this emotional.”

Judge Hart’s voice dropped, quiet and lethal. “No,” he said. “I’m making it lawful.”

He turned to Elias. “Did you sign this contract?”

Elias’s voice was barely audible. “Yes.”

“Were you sober?”

Elias swallowed. “No.”

Judge Hart nodded, as if he’d expected nothing else. Then he looked at Clara, at Lily, at the way Lily leaned into her sister like Clara was the only solid thing in the world. Something in the judge’s expression shifted, not into sentimentality, but into a kind of grim resolve.

“This contract is void,” Judge Hart announced. “It is an illegal attempt to traffic a minor under the disguise of debt repayment. Mr. Blackwell, any further attempt to claim this child will result in immediate arrest and federal charges.”

Blackwell’s mouth opened, outraged. Judge Hart raised a hand. “And you will leave this courtroom now,” he said, “before you say something that proves my point further.”

Blackwell stiffened, eyes burning. He turned sharply and stalked out, his lawyer scrambling after him. The crowd buzzed, half satisfied, half hungry for more.

Judge Hart looked at Elias again. “Now,” he said, and his tone was different, heavy with disappointment. “Mr. Mercer. You have demonstrated that you are unfit to retain parental rights.”

Elias’s face crumpled. “Your Honor, please—”

“Please,” Judge Hart echoed, almost sadly. “You gambled away your child. There are pleas that come too late.”

Clara’s stomach clenched. Part of her had wanted this, had known it was necessary. Another part, smaller and older, still wanted a father, even a broken one. She hated that part of herself for existing.

Judge Hart’s gavel struck once. “Parental rights are hereby terminated,” he said.

Elias made a choking sound. Lily looked up, confused. “Clara,” she whispered, “what does that mean?”

Clara’s throat tightened. She leaned down and pressed her forehead to Lily’s hair. “It means you’re mine,” she whispered back. “And I’m yours.”

Judge Hart’s gaze softened slightly as he watched them. Then he did something that made the room fall silent all over again.

“I appoint Clara Mercer,” he said, “as Lily Mercer’s legal guardian.”

A ripple of shock moved through the crowd. Someone whispered, “She’s just a girl,” and someone else answered, “She’s more of a mother than the man ever was.”

Clara stood frozen, the words hitting her like both blessing and burden. The judge’s eyes held hers.

“You asked this court for protection,” Judge Hart said. “Now the court asks you for capability. Can you provide for her?”

Clara’s mouth felt dry. She wanted to say no, because no was safe, because no meant someone else would carry the weight. But she looked at Lily, and Lily looked back at her with trust so pure it hurt.

“Yes,” Clara said. Her voice shook. “I can.”

Judge Hart nodded once, like a man stamping something permanent. “Then do it,” he said. “And let this town learn what guardianship actually means.”

When Clara and Lily walked out of the courthouse, the air felt different, not kinder, but clearer. A few people stared. A few nodded. Mrs. Danner, the laundry boss, was among them, arms crossed, lips tight. Clara expected criticism, expected a lecture about scandal. Instead Mrs. Danner said, quietly, “Come by tomorrow. I’ll have extra work.”

Clara blinked, surprised.

Mrs. Danner looked away as if generosity embarrassed her. “A girl who reads law books in secret can probably handle an iron,” she muttered. “Don’t make me regret it.”

That night, Clara sat at the table with Lily asleep on a pallet by the stove. The house felt emptier without Elias’s presence, even though his presence had always been a kind of emptiness too. Clara counted her coins, then stopped, because counting didn’t create more. She stared at the wall, mind racing. Judge Hart had given her Lily back, but he hadn’t given her food, shelter, safety. The law could cut chains, but it couldn’t build a home.

So Clara did what she had always done when panic tried to swallow her. She thought.

By morning, she had a plan that tasted like pride and desperation braided together. She put on her cleanest dress, pinned her hair back tight, and walked into town with Lily holding her hand. She went first to the boardinghouse owner, a woman known for hard bargains.

“I’ll work for half wages,” Clara offered. “Cooking, cleaning, laundry. In exchange, you feed and house us both.”

The woman laughed. “Half wages isn’t charity, girl. That’s theft from me.”

Clara nodded once, accepting the refusal without letting it break her. She went next to the hotel manager’s wife. Then to the baker. Then to the seamstress who owned a small shop. Four women, four rejections, each one delivered with the same tired truth: everyone in Silverton was already drowning. No one wanted to pull two more bodies into their water.

By the time she reached the last address, the sky had begun to snow, flakes thin and sharp. The house belonged to Martha Keene, a widow who ran a small dry goods store and lived above it. People said Martha was stern. People also said she never turned away a woman in trouble. Clara didn’t know which rumor was true, only that she had run out of doors to knock on.

Martha opened the door herself, apron dusted with flour, hair streaked with gray, eyes assessing. “Yes?”

Clara swallowed. “My name is Clara Mercer,” she said. “Judge Hart appointed me guardian of my sister. We need work and a place to sleep.”

Martha’s gaze flicked to Lily, then back. “And what are you offering?”

Clara lifted her chin. “Everything I can do,” she said. “Laundry. Cleaning. Stocking shelves. Deliveries. I’ll work longer hours than you ask. I’ll take less pay than you’d give anyone else.”

Martha’s eyes narrowed. “Why would I agree to that?”

Clara’s throat tightened, but she forced the truth out anyway. “Because if you don’t,” she said, “Blackwell will circle back. And next time, I might not have three hours.”

For a moment, the snow was the only sound. Martha Keene stared at Clara like she was measuring her, not her poverty, but her spine. Then Martha stepped aside.

“Come in,” Martha said simply. “You can sleep upstairs. And you’ll work for fair wages, not scraps. I’m not in the business of making another Blackwell.”

Clara blinked hard. “But—”

Martha waved a hand. “You’ll pay me back by staying alive,” she said. “And by keeping the little one in school. Deal?”

Clara’s voice broke. “Deal,” she whispered.

The years that followed were not a montage of easy triumph. They were made of long days stitched together by exhaustion. Clara rose before dawn to sweep the store, haul crates, and scrub floors until her back felt like it might snap. She worked the laundry after closing, hands red and cracked, because clean clothes bought respect in a town that ran on appearances. Lily went to the small public school that had recently opened, carrying books like treasures, and every afternoon she returned to the store to sit at the counter and practice letters while Clara counted inventory.

Sometimes Clara caught Blackwell watching from across the street, his eyes cold, his smile thin. He never approached. Judge Hart’s warning had teeth. But Blackwell’s presence was a reminder: predators didn’t always bite immediately. Sometimes they simply waited for you to get tired.

Clara refused to get tired in the way that mattered.

She saved every coin she could, not by magic, but by sacrifice. She ate less. She wore patched dresses. She learned to mend until the cloth had more mending than original fabric. When Martha Keene let her take on extra laundry contracts from miners, Clara took them. When women came into the store with bruises they tried to hide, Martha quietly offered them a back room and tea, and Clara learned that survival wasn’t just personal, it was communal. The town’s women, tired of being treated like disposable labor, began to recognize Clara as one of their own, not because she was special, but because she was stubborn enough to keep choosing decency.

By 1880, Clara had enough saved to lease a tiny storefront on a side street. She painted the sign herself: MERCER LAUNDRY AND MENDING. Lily, now eleven, stood beside her holding the brush, eyes shining.

“It’s ours,” Lily whispered, as if saying it too loudly might make it vanish.

Clara squeezed her shoulder. “It’s the first thing that’s ours,” she said. “And we’re going to keep it.”

The first months were brutal. Clara rose before dawn to collect laundry, worked all day over boiling tubs, and delivered clean bundles at night, hands raw, hair smelling like soap she couldn’t afford. Some men tried to short her. Some tried to flirt as payment. Clara learned to say no with a smile sharp enough to cut. Lily kept the books, tongue sticking out in concentration as she added columns, learning business the way other girls learned embroidery. And slowly, the coins in the jar began to multiply.

By 1882, Clara bought the building. The day she held the deed, she stared at the paper for a long time, thinking about how different paper could be depending on whose hands it was in. In Elias’s hands, paper had been a noose. In Clara’s, paper became a door.

She hired women next, not girls. Women who had been paid in “room and board” by men like Blackwell. Women who had been told their labor was worth less because their bodies were considered less. Clara paid them fair wages and gave them a safe room above the shop if they needed it. Martha Keene, older now but still sharp, watched it all with quiet satisfaction.

“You’re building a small rebellion,” Martha said one evening, handing Clara a cup of coffee.

Clara shrugged, exhaustion and pride mingling. “I’m building a life,” she said. “Rebellion is just what men call it when women do that without permission.”

When Lily turned eighteen, the town gathered in the laundry to see her off to a teacher training college back east, paid for by Clara’s relentless saving. Lily hugged Clara so hard Clara’s ribs hurt.

“I’ll come back,” Lily promised.

Clara smiled, small and real. “You’d better,” she said. “Someone has to teach this territory how to read the laws they keep breaking.”

Lily returned two years later with books under her arm and fire in her eyes. She taught children in a one-room schoolhouse first, then became principal, then started speaking publicly about the mines and the camps that still used small hands to do dangerous work. Clara sat in the back of those meetings sometimes, arms folded, watching Lily’s voice carry across rooms that once would have ignored girls entirely.

One night, after a particularly heated town hall where a mine owner had snarled that “kids work fine,” Lily came home trembling with anger.

“They don’t care,” Lily said, pacing. “They don’t care if children bleed.”

Clara poured her tea and waited until Lily’s breath slowed. “They care about profit,” Clara said. “So make children too expensive to exploit.”

Lily looked at her. “How?”

Clara tapped the statute book on the shelf, the one she had carried to court years ago. “Laws,” she said. “And enforcement. And shame, if you can manage it.”

Lily’s eyes softened. “You saved me with a book,” she whispered.

Clara’s voice went quieter. “I saved you with time,” she said. “Three hours. And the refusal to freeze when terror showed up at the door.”

Lily stepped forward and took Clara’s hands, older now, callused in different ways. “You never married,” Lily said suddenly, as if the thought had been waiting.

Clara snorted softly. “I raised one child already,” she said, the same line she used when women teased her. “Did a better job than most with half the resources.”

Lily’s eyes filled. “You raised me,” she corrected gently. “And you raised yourself.”

Clara’s throat tightened, but she smiled anyway. “We raised each other,” she said. “That’s the part people don’t write down.”

By 1910, Clara was forty-eight and tired in the way only decades of responsibility could create. Her laundry had employed more than a hundred women over the years. She had helped build a network of safe rooms, fair wages, and quiet rescues that never made newspapers. Lily, meanwhile, had become the first woman in their county to serve as school superintendent, pushing reforms that slowly, stubbornly, began to choke off the worst child labor practices. The mines resisted, of course. Men like Blackwell always resisted. But the world shifted anyway, one ordinance, one inspection, one courageous speech at a time.

When Clara died in 1923, the newspaper called her a successful businesswoman, a pillar of the community, a woman of uncommon grit. The words were true, but they were not the whole truth, and Lily could not let the whole truth be buried with her sister.

At Clara’s funeral, the church was packed with women who had once slept above the laundry because nowhere else was safe. There were grown men too, some with their own children now, men who remembered a girl named Clara Mercer who never begged but always bargained, who never bowed but always worked. Lily stood at the front, hands steady, voice carrying.

“My sister wasn’t powerful,” Lily said. “She wasn’t wealthy. She wasn’t protected. When she was fifteen, she had no weapons, no influence, no connections that mattered. She had a law book, a clear mind, and three hours.”

A hush fell, thick as snowfall.

“She walked into a courthouse and made adults listen,” Lily continued. “She looked at a contract meant to make me property and saw the lie inside it. She taught me that justice isn’t just about punishing wrongdoers. Sometimes it’s about empowering the capable. Sometimes the miracle isn’t a hero arriving. Sometimes the miracle is a girl deciding she will be the hero because no one else has shown up.”

Lily’s voice shook then, but it did not break. “Clara saved me,” she said simply. “And then she spent the rest of her life saving women the way she saved me: by giving them work, shelter, dignity, and the quiet knowledge that their lives were worth fighting for.”

After the service, Judge Hart, old now, hair white, approached Lily with careful steps. His hands trembled with age, but his eyes were still sharp.

“She changed my understanding of the bench,” he said quietly. “I thought justice was only the hammer. She reminded me it could be a key.”

Lily nodded, tears on her cheeks. “She was just capable,” Lily whispered, echoing what she had always known.

Judge Hart’s gaze drifted to the coffin. “That,” he said, voice full of rough reverence, “is a rare kind of just.”

Outside, the mountains stood as they always had, indifferent and beautiful. Silverton had grown, changed, polished itself in places, but the old truths still lived in the grain of its wood and the bones beneath its soil. Somewhere, a child laughed. Somewhere, a woman locked her door at night and knew it would hold. Somewhere, a girl opened a book and discovered that words could be weapons, and that clarity could be a kind of salvation.

And if anyone ever tried again to claim a child like property, there would be people ready, not because the world had become gentle, but because Clara Mercer had proved that gentleness was not the only alternative to cruelty.

Sometimes the alternative was courage.

Sometimes it was capability.

Sometimes it was a sister with three hours and a book in her hands.

THE END

News

THE THORNE HEIRESS RECEIVED THREE ENSLAVED MEN FOR HER BIRTHDAY… AND CHOSE ONE FOR HER BED

In the low, wet country outside Charleston, South Carolina, people liked their explanations tidy. When a child’s fever turned strange,…

THE WIDOWER WHO MARRIED THE “TOO FAT” BRIDE LEFT AT THE RAILROAD STATION

The train pulled away with a groaning hiss, as if even the iron wheels felt guilty about leaving her there….

LONELY RANCHER “BOUGHT” A DEAF GIRL FROM HER DRUNK FATHER—THEN REALIZED SHE COULD HEAR IN A WAY THAT CHANGED THEM BOTH

Texas, 1881 wore its late-autumn heat like a stubborn secret. Even when the calendar insisted the year was cooling, the…

They Dumped the Beaten Mail-Order Bride in the Dirt – Until a Mountain Man Said “Come With Me”

The letter arrived in Boston folded like a small dare. Grace O’Malley held it over her sewing table as if…

THE COWBOY SPENT TWO DOLLARS ON THE WIDOW NO ONE WANTED — AND FOUND HIS ONLY HOPE

The stove in the back of the saloon hadn’t worked right all afternoon, so the heat came in patches: a…

THE “TOO-HEAVY” GIRL MARRIED THE “DEMON” OF CROWTOOTH RIDGE, THEN LEARNED WHO THE REAL MONSTER WAS

Declan’s words sat on the table with the smell of coffee and rabbit fat, heavy as an iron pan. “I’ll…

End of content

No more pages to load