They said I would never marry.

They didn’t say it kindly, either. They said it the way people in polished parlors say anything that makes them feel superior: with a soft laugh, as if cruelty were a form of etiquette. Twelve men in four years came to look at me. Twelve pairs of eyes dropped first to the mahogany wheelchair my father had commissioned, then rose just long enough to offer a practiced apology before retreating to safety.

“My mother requires me in Charleston.”

“I’ve… reconsidered the responsibilities of marriage.”

“It’s not you, Miss Hawthorne. It’s… life.”

But their real words lived behind their teeth.

She can’t walk down the aisle.

She can’t stand beside me at a party.

She can’t chase a toddler across a yard.

She probably can’t bear children.

That last rumor took on a life of its own, as if gossip had lungs. A physician, half-drunk at a supper, speculated about my fertility without ever laying a hand on my wrist. By the next week, women in lace gloves were fanning themselves and whispering as though my body were a broken clock no one could repair.

So I learned to smile. To keep my chin lifted. To pretend the rejection didn’t scrape at my skin like salt.

My name is Clara Hawthorne, and in the spring of 1856, in the lowcountry of South Carolina, I was twenty-two years old and considered—by the polite standards of my world—damaged goods.

My legs had been useless since I was eight.

The riding accident wasn’t dramatic the way novels pretend accidents are. There was no heroic leap, no villainous storm. It was a clean morning with a cruel patch of slick earth. One moment I was laughing at the way the mare tossed her head like an impatient actress; the next, the ground rose up and met me with a certainty that changed everything. My spine shattered in a way no prayer could put back together. I woke in bed with my mother’s rosary pressed into my palm and my father’s voice cracking as he promised me—promised me—that I would still have a life.

He kept that promise the way powerful men keep promises: by spending money until reality looks different.

The wheelchair he ordered was made of dark wood so glossy you could see your face in it. The brass fittings gleamed. The seat was upholstered in velvet. It was a throne disguised as mercy.

But thrones are lonely things when no one wants to sit beside them.

By the time William Pembroke—fat, fifty, and fragrant with whiskey—rejected me despite my father offering him a share of our rice fields’ annual profits, I stopped pretending hope was a sensible hobby.

“I suppose,” I said that night, hands folded neatly over my lap, “that I’m meant to die alone.”

My father’s study smelled of leather and ink and the particular sharpness of fear men think they hide. Colonel Edmund Hawthorne had once stood straight in uniform under a flag and believed the world was built on rules. Age had curved him slightly now, but it had not softened him.

He didn’t look up from the papers on his desk when he answered. “No,” he said. “You are not.”

The words snapped like a whip.

I waited for the familiar lecture about patience, faith, providence. Instead, he set down his pen as if it had become too heavy.

“No white man will marry you,” he said bluntly, and the bluntness was almost a kindness. “That is the reality.”

My throat tightened. “You’ve made that point.”

“You need protection,” he continued, as if protection were a wall you could purchase. “When I die, the estate passes to your cousin Franklin. You know him.”

I did. Franklin Hawthorne visited twice a year, smiled too wide, and looked at our land the way a butcher looks at a fattened calf. He called me “poor Clara” and made jokes about my chair like it was a parlor toy.

“He’ll sell everything,” my father said. “He’ll leave you a pittance and send you to live with relatives who see you as obligation.”

“Then leave me the estate,” I said, though we both knew the law had claws for women.

My father gave a short, bitter laugh. “South Carolina will not allow it. Not in the way you need. And even if paper could hand you land, paper cannot hand you safety.”

“What do you suggest?” I asked, and when I spoke, I heard something sharp in my own voice. Something tired of being managed like furniture.

He held my gaze for a long moment, and in that silence I felt the weight of what he was about to say, the way air presses before a storm.

“I’m giving you to Isaiah,” he said.

The room did not immediately make sense. My mind reached for the nearest Isaiah in my world: Isaiah the stable boy who carried buckets, Isaiah the carpenter’s assistant. But my father’s expression was too deliberate for misunderstanding.

“Isaiah,” I repeated, my voice thinner now. “The blacksmith?”

“Yes.”

I stared at him until my eyes ached. “Father… Isaiah is enslaved.”

“I know exactly what I’m doing.”

The words landed like a stone dropped into water. My thoughts rippled outward, frantic and stunned.

“You cannot mean… marriage.”

He exhaled slowly, as if he had been holding his breath for weeks. “Not a legal marriage recognized by this state,” he said. “But an arrangement. He will be responsible for your care. He will protect you.”

I tasted bile. “Bound by law to stay,” I whispered. “That’s your plan? A man compelled to remain, compelled to serve, compelled to be near me—so I’ll be safe?”

My father flinched, and I realized with a strange clarity that he hated the ugliness of his own solution, even as he clung to it.

“Clara,” he said, voice low, “I have watched you wither under this roof. I have watched polite society carve you into something smaller each season. I will not die and leave you to be destroyed slowly in someone else’s house.”

“So you’ll destroy someone else,” I said, because if I didn’t name it, I would become complicit in silence.

His jaw tightened. “Isaiah is the strongest man on this property. He is intelligent. Gentle, by every report I’ve received. He reads in secret.”

My breath hitched, half surprise and half dread. Reading was forbidden, and punishment for it could be savage.

My father’s eyes sharpened, daring me to question him. “Don’t look shocked. I am not blind. He is… different.”

“He’s a man,” I corrected softly. “Not a tool.”

My father’s shoulders sagged. “Yes,” he said, almost like a confession. “And I am trying to save my daughter in a world that refuses to let her save herself.”

The logic was horrifying and—worst of all—airtight inside the cage of our society.

“Have you asked him?” I demanded.

“Not yet,” he admitted. “I wanted to tell you first.”

“And if I refuse?”

His face aged ten years in a single blink. “Then I keep trying to find a white husband,” he said quietly, “and we both know you will fail, and you will spend your life after I’m gone in boarding houses—dependent on charity from people who resent you.”

The cruelty of the truth made my eyes burn.

I swallowed. “I want to speak to him. Alone. Before you decide both our fates like we’re chess pieces.”

My father nodded once, brisk and grateful. “Tomorrow.”

That night I didn’t sleep. I listened to the house breathe around me—floorboards settling, a distant owl, the soft tick of the clock that had always kept time for people who could walk away from their problems.

In the morning, they brought Isaiah to the main house.

I positioned myself by the parlor window, hands clasped so tightly my knuckles whitened. When I heard footsteps in the hall—heavy ones—the muscles along my spine went rigid with instinctive fear.

The door opened. My father stepped in first. Then Isaiah ducked to clear the frame.

My God.

He was enormous—taller than any man I had ever seen, shoulders broad enough to make the doorway look narrow, arms corded with the strength of forge work. His hands were scarred, calloused, marked by burns that spoke of years handling fire like it was an ordinary acquaintance. His beard was trimmed, his face weathered, and his eyes—dark brown—flicked around the room without settling on me.

He stood with his head slightly bowed, posture trained by punishment into something that looked like obedience and felt like survival.

“Isaiah,” my father said, “this is my daughter, Clara.”

Isaiah’s eyes lifted for half a second and met mine. Then they dropped to the floor again as if eye contact were dangerous.

“Yes, sir,” he murmured.

His voice was deep but quiet, like thunder choosing restraint.

My father cleared his throat. “I have explained the situation. You understand you will be responsible for her care.”

I found my voice, though it trembled. “Isaiah,” I said, “do you understand what my father is proposing?”

Another quick glance—this time longer, as if he were measuring my sincerity.

“Yes, miss,” he said.

“And you’ve agreed?”

He hesitated, and in that pause I heard something that didn’t belong in a slaveholder’s house: confusion.

“I… should, miss,” he said carefully. “But—” His eyes lifted again, braver now. “Do you want to?”

The question startled me so sharply my throat tightened.

My father shifted, uncomfortable with the sudden appearance of choice.

“I’ll be in my study,” he said, and left, closing the door as if sealing us in a storm cellar together.

For a moment, neither of us spoke.

I realized I was holding my breath and forced air into my lungs. “Would you like to sit?” I asked, gesturing to the chair across from me.

Isaiah looked at the delicate, embroidered thing and then at his own frame. “I don’t think that chair would hold me, miss.”

“Then the sofa,” I said.

He sat carefully on the edge, as if afraid even the furniture would accuse him of breaking it. Even seated, he towered over me.

I studied his hands resting on his knees. Each finger looked like it could bend iron—because it probably had.

“Are you afraid of me?” he asked quietly.

The honesty was so unexpected I almost laughed, but laughter felt like a luxury. “Should I be?” I asked instead.

“No, miss,” he said immediately. “I would never hurt you. I swear it.”

“They call you brute,” I said, and watched his face flinch like the word had teeth.

“Yes, miss,” he admitted. “Because of my size. Because I look frightening.”

“You could be frightening if you chose,” I said.

He met my eyes, and in them I saw something that made my stomach twist: sadness. Resignation. Gentleness that didn’t match his body’s legend.

“I could,” he said. “But I wouldn’t. Not you. Not anyone who didn’t deserve it.”

My pulse thudded. I forced myself to speak like the woman I wanted to be instead of the burden society insisted I was.

“I want to be honest with you,” I said. “I don’t want this. Not like this. Not as a cage built for both of us. My father is desperate. I am… I am considered unmarriageable. And he thinks this is the only way to keep me safe.”

Isaiah’s gaze stayed on me now, steady. “I hear you, miss.”

“So tell me,” I said, voice low. “What do you want?”

He gave a humorless breath. “I’m enslaved,” he said. “What I want doesn’t usually matter.”

The words landed with such plain truth that my eyes stung.

“Today,” I said, surprising even myself, “it matters to me.”

Isaiah’s throat bobbed as he swallowed.

“I want…” He stopped, as if wanting were dangerous to say out loud. Then, carefully, “I want to live. I want to keep my people safe when I can. I want to read without fear. I want… freedom.”

The last word was nearly soundless, but it filled the room like smoke.

I nodded slowly. “Can you read?” I asked, because I needed something that wasn’t my father’s plan, something human.

Fear flashed across Isaiah’s face. He glanced toward the door as if expecting it to burst open with punishment.

After a long moment, he said quietly, “Yes, miss. I taught myself.”

“Why?” I asked.

His shoulders lifted and fell. “Books are doors,” he said. “And when you can’t leave a place… you learn to love doors.”

The phrase made something in me unclench.

“What do you read?” I asked.

“Whatever I can find,” he said. “Old newspapers. Sermons. Sometimes books I borrow when no one’s looking.”

I hesitated, then asked, “Have you read Shakespeare?”

His eyes widened as if I’d offered him a treasure. “Yes, miss,” he said, and the excitement in his voice startled me. “There’s an old copy in the library no one touches. I read it at night when the house sleeps.”

“Which plays?”

“Hamlet. Romeo and Juliet. The Tempest.” His voice warmed with each title. “The Tempest is my favorite.”

“Why?” I asked, leaning forward as much as my chair allowed, hungry in a way I hadn’t felt in years.

Isaiah hesitated, then spoke with careful intensity. “Because everyone calls Caliban a monster,” he said, “but the story shows he was taken. His home claimed. His person named savage so someone else can feel righteous.”

The words hung between us like a blade and a plea.

“Who is the monster, then?” I whispered.

Isaiah’s eyes locked on mine. “That’s the question,” he said.

Something inside me shifted. A small, stubborn part of me—the part that had survived twelve rejections—stood up straight.

“Isaiah,” I said, “I don’t think you’re a brute.”

His face tightened as if he were trying not to believe me.

“I think you’re a person forced into an impossible situation,” I continued, “just like I am.”

His eyes shone suddenly, and he looked away quickly, ashamed of tears.

“Thank you, miss,” he murmured.

“Call me Clara,” I said, because I needed the world to change at least one inch. “When we are alone.”

He shook his head, horrified. “I shouldn’t.”

“Nothing about this is proper,” I said, voice sharp. “If we’re to do what my father demands, then I refuse to let it be done with lies and titles that make you smaller.”

His jaw worked. Then, slowly, he nodded once. “Clara,” he said, and my name sounded different in his mouth—gentle, steady, real.

“And you should know,” he added, and the courage in his voice made my throat tighten, “I don’t think you’re unmarriageable.”

I blinked.

“The men who rejected you were fools,” he said simply. “Any man who can’t see past a chair to the person inside doesn’t deserve you.”

No one had spoken to me like that in four years.

My hands trembled. “Will you agree to my father’s plan?” I asked softly.

Isaiah didn’t hesitate. “Yes,” he said. “I’ll protect you. I’ll care for you. And I’ll try to be worthy of you.”

I exhaled like someone releasing a rope they’d been gripping too long. “And I’ll try,” I said, “to make this bearable for both of us.”

We sealed it with a handshake. His enormous palm swallowed my hand, but his touch was careful, as if I were made of glass and dignity.

When my father returned, his relief was immediate and guilty.

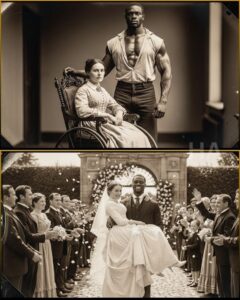

A small ceremony was held on April 1st, 1856, inside our household, away from the eyes of Charleston society. It was not a legal marriage, because the law did not recognize Isaiah as a man with rights. That fact sat like poison under every prayer. My father read Bible verses and announced Isaiah’s new role: not property in the forge alone, but guardian of my welfare.

And in that announcement, my father did something unexpected. He told the household staff, white and enslaved alike, to treat Isaiah with respect in matters concerning me.

It was a thin kind of power, given by a man who still owned him. But it changed the air.

Isaiah was assigned a room adjacent to mine, connected by a door. Propriety was maintained like a curtain drawn over a cracked window.

The first weeks were awkward in a way that made my skin feel too tight. I had been cared for by women who spoke softly and avoided eye contact when my body required help. Now Isaiah had to assist me with tasks that felt humiliating even when done kindly.

But he approached everything with a gentleness that made shame harder to hold.

When he lifted me from chair to bed, he asked permission first.

“May I?” he would say, voice careful.

When he helped me dress, he kept his gaze averted as though my dignity were a fragile heirloom.

“I know this is uncomfortable,” I told him one morning, watching him reorganize my bookshelf after I mentioned—once—that I wished it were alphabetical.

He didn’t look up from the spines. “Yes, miss,” he said automatically, then corrected himself, almost smiling. “Yes… Clara.”

“And you didn’t choose this,” I said. “Neither did I.”

Isaiah knelt beside the shelf, and in that position—so large yet so contained—he looked less like a myth and more like a man tired of being shaped by other people’s fear.

“I’ve been enslaved my whole life,” he said quietly. “I’ve worked heat that would kill most men. I’ve been punished for mistakes made by others. I’ve watched family sold away like furniture.”

My throat tightened.

He gestured around my comfortable room. “Here, I get books. I get conversation. I get… you treating me like I have a mind.”

“Yet you’re still enslaved,” I said.

“Yes,” he answered, and the word held a world. “But I’d rather be here with someone who sees me than alone somewhere else with no one.”

The honesty made my chest ache.

By the end of April, we had a routine. Mornings he helped with my preparations and carried me when the chair couldn’t manage stairs. Then he returned to the forge. I handled household accounts. Afternoons we spent time together: sometimes I watched him work, fascinated by the way he turned iron into useful grace. Sometimes he read to me, stumbling at first but improving quickly as I corrected him gently.

One evening, I asked him to read poetry. Keats, because I needed beauty that wasn’t made of silk and cruelty.

His voice filled the room, deep and steady.

“A thing of beauty is a joy forever,” he read, and the words felt like a dare to the universe.

“Do you believe that?” I asked when he paused.

Isaiah considered. “I think beauty in memory lasts,” he said. “The thing itself might fade. But what it gave you… that remains.”

“What’s the most beautiful thing you’ve ever seen?” I asked, and the question felt childish, but I wanted to hear him speak of wonder.

He was quiet long enough that I began to regret asking. Then he said softly, “You.”

Heat rose to my face like a sudden flame.

“Yesterday at the forge,” he continued, voice firming, “covered in soot, sweating, laughing when you managed to bend the nail. That was beautiful.”

My heart stuttered.

“I shouldn’t have said that,” he added quickly, shame flashing.

“No,” I whispered, rolling my chair closer. “Say it again.”

Isaiah’s eyes met mine. “You are beautiful, Clara,” he said. “The chair doesn’t change it. The legs that don’t work don’t change it. You are brave and sharp-minded and kind. And anyone who couldn’t see that was blind.”

I reached out and took his hand. His scarred fingers curled around mine with reverence.

“Do you see me?” I asked, voice small despite my effort.

“Yes,” he said, and his certainty made me want to weep. “I see all of you.”

The next words left my mouth before fear could stop them. “I think I’m falling in love with you.”

Silence struck the room like lightning.

We were in South Carolina. In 1856. In a world built on cruelty dressed as law. There was no space for what I’d just admitted.

Isaiah’s face tightened with something like grief. “Clara,” he said carefully, “you can’t.”

“Why?” I demanded, and the desperation in my voice startled me. “We’re already living in scandal’s shadow. My father already put us together. What difference does love make?”

“The difference is punishment,” he said, voice rough now. “Your safety. My life.”

“If people think this is affection instead of obligation…” He swallowed. “They will use it to destroy you. And they will use you to destroy me.”

I cupped his face with my hand, reaching up as far as I could. “I don’t care what they think,” I whispered fiercely. “I care what I feel. And I feel like someone has finally seen me. Not the chair. Not the burden. Me.”

Isaiah’s eyes shut for a moment as if he were praying for strength. When he opened them, they were wet.

“I’ve loved you since our first real conversation,” he said, voice breaking. “When you asked me about Shakespeare and listened. When you spoke to me like I was human. I have loved you every day since.”

“Then say it,” I whispered.

He exhaled like a man stepping off a cliff. “I love you.”

Our first kiss happened in the library, surrounded by books that would condemn us and still somehow felt like witness rather than judge. His lips were gentle, hesitant, as if he were afraid I would shatter.

I did not shatter.

For five months, Isaiah and I lived inside a fragile bubble, careful in public, cautious in hallways, dutiful before servants and overseers. But in private, we were simply two people who had found each other in a world determined to keep them alone.

And then, on a cold December evening, the bubble broke.

We were in the library again. I had just pulled Isaiah down toward me, hungry for the small freedom of being held. I didn’t hear my father’s footsteps. Didn’t hear the door open.

“Clara.”

My father’s voice was ice.

We sprang apart. Isaiah dropped instantly to his knees, training overriding love.

“Sir,” Isaiah said, voice shaking. “Please. This is my fault.”

My father’s eyes were fixed on me, not on Isaiah. Shock, anger, and something else I couldn’t name warred across his face.

“You’re in love with him,” he said, not a question but an accusation soaked in disbelief.

I could have lied. I could have claimed Isaiah forced me, played the helpless victim, saved my reputation by sacrificing his life.

The thought made me sick.

“Yes,” I said, voice trembling but clear. “I love him. And he loves me. And it was mutual.”

My father’s lips parted slightly, as if he’d been struck.

“Isaiah,” he said, voice dangerously calm, “go to your room. Do not leave until I send for you.”

Isaiah stood slowly, casting one anguished look back at me before obeying. The door closed.

My father and I were alone with the truth.

“Do you understand what you’ve done?” he asked quietly.

“I’ve fallen in love with a good man who treats me with respect,” I shot back, years of bitterness boiling. “Something no man of my class has ever managed.”

“You’ve fallen in love with a man I own,” he said, and the words were a wound he finally looked at.

The bluntness of it silenced me for a moment.

“If this becomes known,” he continued, voice tight, “you will be ruined beyond redemption. They will call you mad. Perverse. Defective.”

“They already call me defective,” I said, and the laugh that escaped me sounded like broken glass. “What’s the difference?”

“The difference is violence,” my father snapped. Then he stopped, as if hearing himself finally. He rubbed a hand over his face. “I gave you to him to protect you,” he whispered. “Not… not for this.”

“Then you should not have put us together,” I said fiercely. “You should not have handed me to someone kind and intelligent and expected my heart to remain obedient.”

My father sank into a chair, suddenly older than I’d ever seen him. “What do you want me to do?” he asked, voice frayed.

“Free him,” I said. “Let us leave. We’ll go north.”

He flinched, as if the word north were a blade. “The North is not a paradise,” he warned. “A white woman with a Black man will face hatred everywhere.”

“I don’t care,” I said. “Being without Isaiah will destroy me. For the first time in my life, I am not a burden. I am loved.”

Silence stretched. Outside, wind rattled the window like impatient fingers.

Finally, my father spoke again, and his next words chilled my blood.

“I could sell him,” he said quietly. “Send him deep south. Make sure you never see him again.”

My breath stopped.

He held up a hand as I began to plead. “That is what society would call the proper solution,” he said, voice raw. “Separate you. Pretend this never happened. Find you an arrangement.”

“Please,” I whispered, and my pride cracked like thin ice. “Don’t.”

My father’s eyes were wet, and the sight shocked me more than his threat. “But I won’t,” he said, voice shaking. “Because I have watched you these past months. I’ve seen you smile more than you have in fourteen years. I’ve seen you become… yourself again.”

He swallowed hard. “I do not understand this. It goes against everything I was taught. But you are right. I created this situation.”

Hope flickered, small and trembling.

“I need time,” my father said. “To find a solution that doesn’t end with either of you destroyed.”

When he left the library, my heart was pounding so hard I felt it in my teeth.

Isaiah was summoned an hour later, fear pale on his face. I told him what my father had said. When Isaiah realized he wasn’t being sold, he sank into a chair and covered his face with his hands, crying with a relief so deep it looked like pain.

I reached for him from my wheelchair, pulling him close as far as I could. He wrapped his arms around me carefully, holding me as if I were the last good thing in a burning world.

Two months passed in anxious suspension. We continued our routines, but every day felt like waiting for a verdict.

Then, in late February 1857, my father called us both to his study.

“I’ve made my decision,” he said without preamble.

Isaiah stood beside my chair, his hand resting lightly on my shoulder, a secret comfort disguised as duty.

“There is no way to make this work here,” my father said. “Not in this state. Not in the South. The laws forbid it, and society would turn suspicion into violence.”

My stomach sank, bracing for separation.

“So,” my father continued, voice firm, “I’m offering you an alternative.”

He looked directly at Isaiah.

“Isaiah, I am going to free you. Legally. Formally. With documents that will stand in a northern court.”

The room blurred. I couldn’t breathe.

My father turned to me. “Clara, I am giving you funds enough to establish a new life. And letters of introduction to abolitionist contacts in Philadelphia. You will leave this place before gossip becomes a noose.”

My hands flew to my mouth. Tears spilled before I could stop them.

“You’re… letting us go?” I choked.

“Yes,” my father said, voice thick. “And I will arrange a legal marriage where it can be recognized.”

Isaiah made a sound that was half sob, half laugh. He dropped to his knees again, not from training this time but from being overwhelmed.

“Sir,” Isaiah whispered, “I don’t… I can’t…”

“You can,” my father said sharply, and then softer, “and you will.”

He paused, and when he spoke again, his voice carried the weight of a man paying for his own awakening.

“You protected my daughter better than any man I tried to buy,” he said to Isaiah. “You made her happy. In return, I am giving you your freedom… and the woman you love.”

I reached for my father’s hand, clutching it like a lifeline. “Thank you,” I whispered.

“Don’t thank me yet,” he said. “This will cost. It will cost reputation. It may cost safety. It will cost me people who once called me friend.”

Then he looked at me, the way he had looked when I was eight and broken on the ground.

“Are you certain?” he asked.

I lifted my chin. “More certain than I’ve ever been.”

Isaiah’s voice shook with fierce devotion. “I’ll spend my life making sure she never regrets this.”

My father nodded once, briskly, as if the nod were holding him together. “Then we proceed.”

The next week was a blur of documents, whispered meetings, and preparations done at night as if freedom were contraband. Isaiah’s manumission papers were drafted with careful legal language. My father’s signature cut across the page like a blade.

A sympathetic minister performed our wedding quietly in a small church outside the city, where the law didn’t spit on our vows. When Isaiah took my hands, his palms were warm and trembling.

“I have nothing to offer you,” he whispered.

“You offer me yourself,” I said. “That’s everything.”

On March 15th, 1857, we left South Carolina in a private carriage my father arranged, our belongings in two trunks: clothes, Isaiah’s tools, my books, and the freedom papers Isaiah carried as if they were holy.

My father embraced me before we departed. His arms were tight, almost desperate.

“Write to me,” he said, voice rough. “Let me know you’re safe.”

“I will,” I promised. “And Father… I love you.”

He swallowed hard. “I know,” he said. “Now go. Be happy. You deserved that long before this world agreed.”

Isaiah shook my father’s hand. “With my life, sir,” Isaiah said.

My father’s eyes glistened. “That’s all I ask.”

We traveled north through roads that felt like crossing into another universe. Isaiah watched every mile like it might suddenly turn into a trap. But the papers held. The world, for once, didn’t slam a door.

When we crossed into Pennsylvania, Isaiah exhaled a breath I think he’d been holding his entire life.

Philadelphia in 1857 was loud, crowded, alive. It smelled of coal smoke and bread and possibility. Abolitionist contacts helped us find lodging in a neighborhood where free Black families lived, worked, and built lives in defiance of the nation’s hypocrisy.

Isaiah opened a blacksmith shop with the funds my father provided. People came first out of curiosity, then out of respect. He was skilled, reliable, and his immense strength made him capable of work other smiths couldn’t manage.

I handled accounts and contracts, and for the first time, my education mattered. My mind wasn’t a decorative thing. It was a tool, sharp and necessary.

When our first child arrived in late 1858, Isaiah held our son with such careful tenderness that I wept openly, overwhelmed by the sight of a man once called brute becoming a father with hands that gentled instinctively around something small and new.

Years passed. Children followed. Our home filled with noise and arguments and laughter, the kind of life that isn’t perfect but is real, stitched together by work and devotion.

And then, one winter in the mid-1860s, Isaiah did something that made me stare at him as if I’d never truly understood who he was.

He designed braces for my legs. Metal supports crafted at his forge, fitted carefully to my body, paired with crutches he adjusted until the weight distributed in a way that didn’t crush my hips.

“I don’t want you hurt,” he said, brow furrowed in concentration as he tightened a strap.

“I’ll be careful,” I promised, voice shaking.

He knelt before me, eyes fierce. “You’ve been careful your whole life,” he said. “Now… try brave.”

The first time I stood, my arms trembled. Pain flared. Tears spilled. But I stood.

Isaiah steadied me as if he were anchoring the earth.

“Look at you,” he whispered, awed.

I took one shaky step. Then another. Each movement felt like a prayer answered by metal and love.

“You gave me so much,” I sobbed, gripping his shoulders. “You gave me love. A life. And now you’ve given me this.”

Isaiah kissed my forehead. “You always had strength,” he murmured. “I just gave you different tools.”

In 1870, a letter arrived bearing my father’s handwriting. The paper felt heavier than it should have.

My father had died.

He left me no land. The law still snarled. But he left me words, and sometimes words are the only inheritance that heals.

My dearest Clara, the letter began. By the time you read this, I’ll be gone. I want you to know: giving you to Isaiah was the smartest decision I ever made, though it began in desperation and sin. I thought I was arranging protection. I did not realize I was arranging love. You were never unworthy. The world was too blind to see your worth. Thank God Isaiah wasn’t. Live well, my daughter. Be happy. You deserve it.

I read it twice, then pressed it to my chest until the paper wrinkled.

Isaiah didn’t speak while I cried. He simply held me, steady and patient, the way he had held me through every new fear.

We grew old in Philadelphia. We watched our children become adults and build lives that would have been illegal where we began. We argued about small things, laughed about sillier ones, and held each other through grief and illness and the daily ache of living in a country that learned progress slowly, like a stubborn student.

When sickness took me in the spring of 1895, it did not feel dramatic. It felt like fatigue settling deeper each day until even breathing seemed like a chore.

Isaiah sat beside my bed, holding my hand as if his touch could anchor me to the world.

“Thank you,” I whispered, voice thin. “For seeing me. For loving me. For making me whole.”

Isaiah’s face crumpled. “You made me whole first,” he said, voice broken. “You looked at me and saw a man.”

I died with his hand in mine.

The doctor said Isaiah’s heart failed the next day, as if it simply refused to keep time without mine. Our children said no, quietly. They said his heart did exactly what it had always done.

It chose love over survival.

We were buried side by side, our names carved into one stone, not because society had finally approved, but because our family insisted on truth.

And if anyone asks what changed history, I won’t pretend it was romance alone.

It was a chain of choices that began in ugliness and evolved into courage: a father confronting the limits of his world, a man claiming his humanity in a system built to deny it, and a woman refusing to be reduced to the chair beneath her.

In the end, love did not erase injustice.

But love did what it has always done at its best: it made two abandoned people into a home.

THE END

News

He Brought His New Wife to the Party—Then Froze When a Billionaire Kissed His Black Ex

The invitation arrived in a thick, cream envelope that looked like it had never known the inside of a mailbox….

Billionaire’s Son Pours Hot Coffee on Shy Waitress –Unaware The Mafia Boss Saw Everything

The first scream didn’t belong in a place like The Gilded Sparrow. The cafe sat in San Francisco’s financial district,…

In Court, My Wife Called Me “A Useless Husband” — Until The Judge Asked One Question…

The clock above the judge’s bench read 9:14 a.m. and sounded louder than it should have, as if every second…

“‘By Spring, You Will Give Birth to Our Son,’ the Mountain Man Declared to the Obese Girl”

Snow fell like quiet verdicts, one after another, flattening the world into a white that felt too clean for what…

Choose Any Woman You Want, Cowboy — the Sheriff Said… Then I’ll Marry the Obese Girl

The first light of morning slid through the thin cracks in the cabin wall like it was ashamed to be…

Muhammad Ali Walked Into a “WHITES ONLY” Diner in 1974—What He Did Next Changed Owner’s Life FOREVER

The summer heat in the American South had a way of pressing itself onto everything, like a palm that refused…

End of content

No more pages to load