The powerful did not like mysteries. They liked problems that could be purchased, buried, or blamed on someone without a last name.

This one felt like none of those.

The District That Fed on Silence

In the lowcountry where the Ogeechee and the Savannah braided through marsh and mud, a handful of families owned so much land it looked like God had signed deeds in their favor.

They hosted dinners with silver candlesticks that could buy a man’s freedom ten times over, and they spoke about honor the way a banker speaks about interest: confidently, as if the numbers could never turn against them. They drank brandy and smoked cigars while the enslaved moved like shadows behind their chairs, refilling glasses, catching fragments of conversation the way you catch sparks before they fall into the rug.

Caleb had been raised near enough to those estates to know the illusion and the cost of it.

He was not born into plantation money. His father had been a boat carpenter with hands like oak roots and a habit of coming home tired in a way that made silence feel safer than speech. Caleb learned early that people could be powerful and still afraid, that they could be respected and still rotten, and that the line between the two was often nothing more than a clean coat.

He also learned that the enslaved were expected to be deaf.

The families never said so outright, but they lived by it. They spoke openly in parlors as if the human beings pouring their tea were furniture. They argued about politics in the presence of men who could not legally read the law. They confessed their appetites in half-jokes while women in headwraps stood close enough to smell their breath.

If you wanted to hide something in the district, you hid it in plain sight.

And if you wanted to spread something, you whispered it in a kitchen doorway.

By the time Caleb rode out to Rivergate after Kincaid’s body was identified, the estate was already dressed in grief like it was preparing for a portrait.

Abigail Kincaid stood on the front steps, spine straight, jaw tight, eyes dry. She wore black with the precision of someone used to wearing responsibility. Behind her, the house servants moved carefully, the way people move when a floor might collapse.

Caleb watched Abigail’s gaze flick past him and settle on the yard, where the enslaved field hands had been gathered by the overseer and lined up as if ordered to be visible for once.

Abigail’s voice was steady when she spoke. “Sheriff Voss. Tell me you’ve found who did this.”

Caleb met her eyes and saw something sharp behind the composure, something that looked less like grief and more like calculation.

“I’m going to ask questions first, ma’am,” he said.

“Ask them,” she replied. “I’ve already survived a marriage. I can survive an interrogation.”

That line lingered with a strange bitterness, and Caleb filed it away. Not because it proved anything, but because it smelled like a crack.

He asked about Kincaid’s last days: where he’d been, who he’d seen, what he’d said. Abigail answered without hesitation.

“He was in Savannah three nights ago,” she said. “He had meetings. Investors. He told me it was important.”

“Did he seem afraid?”

Abigail’s lips pressed into a thin line. “Thomas didn’t do fear. He did impatience. He did ambition. Sometimes he did guilt, but only when it was convenient.”

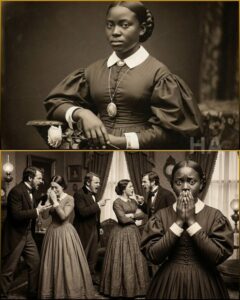

Caleb glanced toward the side porch where a woman stood half-hidden behind a column, holding a basket of linens. She had a stillness that made her noticeable, which was almost a contradiction. Most people who lived under someone else’s authority learned the art of being forgettable.

This woman looked like she’d decided to be seen, but only on her terms.

Abigail followed Caleb’s glance and said, “That’s Violet. She helps with the house.”

Violet.

Caleb didn’t ask more then. Something in him cautioned patience, the way the river cautions you before it pulls.

Because that name wasn’t ringing in his head like a bell.

It was ringing like a warning.

Two Summers Earlier

In June of 1837, before the river began delivering sermons, a young woman arrived at Cypress Hollow as part of an estate settlement out of Savannah.

Her name on the paperwork was Lena, and the description was too careful, too admiring for a document that treated her as property: light-brown complexion, graceful manner, trained in household service, “refined.” A note in the margin stated she was to be taken a certain distance from the city, as if geography could cleanse a reputation.

The buyer, Senator Gideon Halloway, did not ask why.

He told himself he’d purchased a tool for his wife. A competent servant. An investment in efficiency. He liked that story because it made him feel civilized.

His wife, Clarissa Halloway, approved the moment she saw Lena step out of the wagon.

Lena held herself with a composure that looked like pride until you recognized it for what it was: control. Her hair was tied back, her hands folded, her gaze lowered in the practiced manner of someone who understood exactly how much eye contact could cost.

Clarissa said, “She’ll do,” the way you might say a chandelier fits.

Lena was assigned to manage correspondence, household schedules, and the social demands that came with Gideon’s rising political career. She could read and write, though no one boasted about that fact the way they might brag about a fast horse. Literacy in an enslaved woman was a candle in a powder room: useful, dangerous, and best hidden behind proper drapes.

For months, Lena performed exactly what was expected. She was efficient, quiet, almost eerily predictive, as if she could anticipate needs before they were voiced. The other house servants accepted her because she did not threaten their small hierarchies; she made herself useful without making herself beloved.

But beneath the surface, she watched.

Not in the obvious way, not with staring eyes that begged suspicion, but with the kind of attention that belonged to someone who had long ago learned that survival depended on reading the room better than the room read you.

She noticed Gideon’s habits: the way he lingered near the bourbon decanter when he was frustrated, the way he spoke softly when he wanted something to sound noble, the way his laughter changed around women who did not challenge him.

She noticed Clarissa’s habits too: the way she tightened her grip on her fan when Gideon praised someone else, the way she smiled with her mouth but not her eyes when she was performing hostesshood like a duty.

And she noticed the gap between them.

A marriage could look flawless from the road and still be empty as a drained well.

That gap was not Lena’s creation, but she recognized it as an opening. And openings, in her world, were the closest thing to doors.

One cold evening in December, after Gideon returned from Atlanta with his temper frayed by legislative fights, Lena brought coffee to his study. She set the tray down quietly. She should have left. That was the rule.

Instead, she said, in a voice carefully measured, “Sir, you look like a man carrying more than his hands were made for.”

Gideon looked up sharply.

Servants weren’t supposed to interpret your face. They were supposed to dust around your moods like furniture.

“What did you say?” he asked.

Lena lowered her eyes, as if retreating, but not fully. “Nothing disrespectful. Only… a man can be surrounded and still be alone.”

It was a dangerous observation, not because it was loud, but because it was accurate.

Gideon leaned back in his chair and studied her the way he studied political opponents: searching for motive.

“You speak like you’ve been educated,” he said.

“I’ve been alive,” Lena replied, and for a second the words felt like a slap dressed in velvet.

She left before the silence could become accusation, but the seed had been planted. Gideon told himself it was nothing. A moment. A strange remark.

Yet over the next weeks, he found himself creating reasons to summon her. Small questions about household accounts. Letters he could have dictated to anyone. Trivial tasks that became excuses.

He liked the way she listened.

It wasn’t flattery. It wasn’t giggling charm. It was focus, as if his thoughts mattered beyond their usefulness. Gideon, who lived inside the constant noise of ambition, began to crave that kind of quiet attention like a starving man craves bread.

Lena did not offer romance. She offered recognition. She made Gideon feel seen in a life where he was constantly looked at.

That was the first trap, and he stepped into it willingly.

When Clarissa traveled to Charleston in late February, the house grew quieter. Gideon drank more brandy than usual. One night, he asked Lena to stay in the study “for a moment.”

They spoke for nearly an hour, and what passed between them was not tenderness so much as confession. Gideon spoke about disappointment, about the hollowness behind his public image, about the loneliness he couldn’t admit without ruining the story he’d built about himself.

Lena listened.

And when Gideon finally crossed the boundary he knew existed, when his need and entitlement collided into something he called desire, it was not a love scene. It was an abuse of power wrapped in the illusion of mutuality, the oldest lie in the South.

After, Gideon looked wrecked by guilt.

Lena looked calm, which was what frightened him later.

“This doesn’t have to destroy you,” she said quietly.

Gideon’s voice cracked. “If anyone finds out…”

“They’ll ruin you,” Lena agreed. “And they’ll sell me. Or worse.”

He nodded, horrified, and in that moment he thought he was sharing fear with her. He didn’t understand yet that fear was the only currency he had, and she had already learned how to spend it.

Because when she added, softly, “So you’ll want me as an ally,” Gideon heard the truth underneath the gentleness.

He had just placed his reputation in the hands of someone the law insisted had no hands at all.

The Loan That Looked Like Generosity

By spring, Clarissa Halloway was boasting about Lena’s competence at dinners, the way wealthy women bragged about porcelain: proof of taste, proof of control.

When Abigail Kincaid mentioned she needed more sophisticated household help to climb into the district’s highest circles, Clarissa suggested a “temporary loan” of Lena’s services.

Gideon objected privately. Not because he cared about Lena’s welfare, but because he cared about access to her. He was trapped in appetite and guilt, and he hated himself for it, which made him cling harder.

Clarissa overruled him.

She framed it as generosity, as strategy, as social dominance. Lending your best servant was a way to remind other families who sat at the top.

Lena went to Rivergate in June of 1838.

There, she adjusted her method like a musician changing keys.

Thomas Kincaid was not lonely like Gideon. He was hungry for admiration, the kind of man who needed applause the way other men needed oxygen. His wife’s coolness did not wound him because he wanted love; it wounded him because it suggested he wasn’t winning.

Lena became his mirror.

She praised his business instincts when Abigail questioned them. She admired his vision when others called it reckless. She made him feel like the hero of his own story.

When he began seeking her company at odd hours under the pretense of “correspondence,” Lena did what she had learned to do: she let him believe he was choosing.

And when Gideon Halloway began riding downriver with flimsy excuses, restless and resentful, Lena recognized the shape of a larger fire.

Two powerful men. Two egos. Two marriages built on performance.

All it would take was a spark.

Lena fed Thomas carefully selected truths about Gideon’s maneuvers, about regulatory obstacles and whispered rumors, about political sabotage dressed as civic concern. The truths were real, which made them lethal.

By October, Thomas confronted Gideon publicly at a planters’ meeting. Their words were sharp enough to slice reputations. Their feud became the district’s favorite entertainment, because watching powerful men bleed socially made other powerful men feel safer.

While they fought in public, Lena listened in private.

She gathered names. She gathered debts. She gathered secrets the way a seamstress gathers pins, because you never knew which one would hold the whole thing together.

And she began to understand something else too, something that made her stomach twist even as it sharpened her resolve:

Every man who claimed the right to own her also believed himself righteous.

That hypocrisy was an engine. Lena decided to feed it until it exploded.

Mercy in the River

Thomas Kincaid’s death did not feel like a spontaneous crime. It felt like a message.

Sheriff Caleb Voss suspected business rivals first, because that was what the district always offered: a man with money dies, blame money.

He interviewed investors, creditors, tavern owners, and rivals. He heard about Kincaid’s agitation, his drinking, his muttered comments about betrayal and justice. He heard that he’d been seen in Savannah’s waterfront district three nights before his body surfaced.

But every path Caleb followed turned into fog.

Then he heard something else. Not from a planter. Not from a respectable mouth.

From a dockworker, half-drunk on cheap rum, who leaned in close and said, “Sheriff, I ain’t sayin’ nothin’ official, but folks been whisperin’ about a woman.”

“A woman,” Caleb repeated, skeptical.

The dockworker shrugged. “A woman that moves like she got no chains. A woman men get stupid around.”

Caleb wanted to dismiss it as tavern nonsense. The district loved blaming women for men’s failures; it was one of its oldest habits.

Still, he couldn’t shake the word on Kincaid’s back.

MERCY.

It didn’t sound like a man’s revenge. It sounded like a judge.

And judges, Caleb knew, could wear any face.

The Web That White Eyes Didn’t See

If Caleb had been born into the plantation world, he might have missed what he eventually noticed.

But he grew up watching the enslaved navigate white spaces like water navigates cracks. Quietly. Persistently. With an intelligence that was never credited and always used.

He began asking questions that made planters uncomfortable: not just “Who had motive?” but “Who had access?”

He noticed how news traveled. He noticed how quickly certain rumors spread and how slowly others died. He noticed that the enslaved in town seemed to know more about the district’s private conflicts than the district admitted to itself.

And then, as if the river had decided Caleb was ready, the second death landed like a stone.

In July of 1839, Gideon Halloway was found in his study at Cypress Hollow, wrists cut, a confession letter beside him describing “sin,” “shame,” and a “woman he could not resist.” The district swallowed the scandal with horror and fascination.

Clarissa Halloway did not weep in public. She stood at the funeral with her chin high, eyes glacial, as if she’d been carved from the same marble that lined Savannah’s banks.

Caleb read the note. The handwriting matched Gideon’s. The language did not.

It was too clean. Too composed. Like a speech written for a crowd instead of a plea meant for God.

Caleb didn’t say that out loud either. He simply began to look backward, tracing the line of disasters as if he were following footprints in sand.

Thomas Kincaid. Gideon Halloway.

Two men connected by a feud. Two men connected by a household servant loaned between estates.

Caleb rode back to Rivergate and asked Abigail Kincaid who had managed the household correspondence that year.

Abigail hesitated for the first time. It was small, but Caleb caught it.

“A woman named Violet,” she said.

“Where is she now?” Caleb asked.

Abigail’s gaze flicked toward the yard, toward the quarters. “She’s… gone. After my husband’s death, I dismissed several staff. I didn’t need reminders.”

“What was her name before Violet?” Caleb asked softly.

Abigail’s eyes narrowed. “Why are you asking me this, Sheriff?”

“Because I don’t think your husband’s death began on the night he disappeared,” Caleb said. “I think it began the moment someone learned how to reach him.”

Abigail’s mouth tightened. “Her name was Lena at Cypress Hollow, I believe. Clarissa Halloway’s servant. But she isn’t here now. She left months ago.”

“Left,” Caleb repeated, tasting the word.

In the South, enslaved people didn’t “leave.” They were sent. They were sold. They were taken.

Or they ran.

Caleb’s attention shifted, slow and inevitable, like a tide turning.

“Where did she go?” he asked.

Abigail’s voice sharpened. “Sheriff, you’re not suggesting what I think you’re suggesting.”

“I’m suggesting I don’t know what I’m suggesting yet,” Caleb answered. “But I know this: the people you assume are powerless are often the ones most practiced at moving without notice.”

The Third House: A Journal of Sins

The next crack in the district’s foundation came not from a corpse in water, but from paper.

Colonel Silas Langford of Ironwood, old money and older cruelty, began to unravel in the fall of 1839 when pages from his private journal surfaced in places they had no business being.

A creditor received a page detailing illegal loans. A planter’s wife received a page describing an affair with an enslaved woman. Caleb received a page describing a beating that ended in death, hidden behind lies and church attendance.

The district erupted.

Langford’s wife fled to Virginia. His creditors circled. His sons argued openly in town. And when Silas Langford was found hanging in his stable that winter, it looked like suicide.

Caleb stood in the stable and stared at the rope.

He didn’t announce his doubts. He simply watched the way the knot lay, tidy and certain.

He thought about ships. He thought about docks. He thought about the way Savannah’s river people tied lines.

And he thought again about the dockworker’s half-drunk warning.

A woman men get stupid around.

By then, “Lena” had become a shape in his mind. Not a single face yet, but a pattern: intelligence, access, invisibility weaponized.

Caleb’s superiors wanted closure. The governor’s office wanted silence. Planters wanted someone disposable to blame, someone who could be punished without touching the district’s pride.

Caleb wanted the truth.

The truth, he suspected, would not be convenient.

The Seamstress Who Couldn’t Keep Quiet

In February of 1840, a free Black seamstress named Nora Bell asked to speak with Sheriff Caleb Voss.

She met him behind the courthouse, away from windows, her hands trembling as she clutched a bundle of cloth like a shield.

“I don’t have much time,” she said. “And I don’t know if I’m doing right. But I can’t sleep anymore.”

Caleb waited.

Nora swallowed. “There’s a woman. She’s staying in a boarding house near the market sometimes. She uses different names. Folks call her different things. But I know who she is.”

Caleb’s pulse steadied into focus. “Tell me.”

Nora’s eyes glistened with fear. “They called her Lena once. She told me she was free before they stole her freedom. She told me she’s been making certain men face what they’ve done.”

Caleb kept his face still, but inside his mind something clicked into place like a lock turning.

“Where is she now?” he asked.

Nora shook her head quickly. “I don’t know exactly. That’s the thing. She’s always moving. But she mentioned one name like it mattered. Like it was the last chapter.”

“Whose name?” Caleb asked.

Nora’s voice dropped to a whisper. “Everett Devereaux. The young widower out near Darien. The one who studied in Europe.”

Caleb knew Devereaux by reputation: charm, education, money that wasn’t as old as it pretended to be. A man who hosted dinners with French wine and talked about progress while keeping the same chains on his land that everyone else did.

If Lena was aiming at him, Caleb suspected she had found something rotten beneath the polish.

He thanked Nora quietly, then did the one thing that felt both necessary and doomed:

He rode for Devereaux’s estate with all the speed a horse could offer through marsh roads.

He arrived too late.

Everett Devereaux was found dead in his study, a confession letter on the desk detailing a scandal from Paris, a young woman’s death, guilt written in ink like a grave marker. The scene looked like suicide.

Caleb read the confession and felt cold.

It explained everything and nothing. It accounted for Devereaux’s death but did not touch Georgia’s river sermons. It gave society a neat box to close and nail shut.

Caleb stared at the body, at the careful arrangement, at the way the room smelled faintly of soap as if someone had cleaned more than dust.

He didn’t need fingerprints. He didn’t need a witness.

He recognized the style.

He stepped outside and looked at the horizon where the marsh met sky, a blurred line that made distance feel like possibility.

“She’s still here,” he murmured.

And somewhere in the district, he sensed, a woman was breathing calmly, waiting.

The Confrontation the District Would Never Admit Happened

Caleb spent weeks doing what no one wanted him to do: he traced the quiet routes.

Not roads. Not official channels. The hidden arteries of Savannah: markets, docks, kitchens, wash yards, church steps where the enslaved gathered on Sunday afternoons under the watchful gaze of men who believed surveillance equaled control.

He followed rumors until they became shapes. He followed shapes until they became patterns. And one rain-heavy evening in March of 1840, he walked into a boarding house near the market with no deputies and no badge visible, because he knew force would only send the truth slipping through his fingers.

The proprietor, a stern woman with sharp eyes, tried to block him.

“I’m looking for someone,” Caleb said calmly.

“You’re always looking,” the woman replied.

“I’m not here to cause trouble,” Caleb said, though they both knew trouble had been following him like a shadow.

The woman studied him, then jerked her chin toward the back.

“Ain’t my business what ghosts you chase,” she muttered.

Caleb stepped into a small room lit by one oil lamp. A woman sat at a table, hands folded, posture composed. She wore a plain dress. No jewelry. No dramatic veil. Just a quiet, deliberate presence.

Her face was the face Caleb had been trying to see in his mind for months, and now that it was in front of him, it looked almost ordinary.

Which was the most frightening part.

“You’re Lena,” Caleb said.

The woman’s expression didn’t change. “That’s one name.”

Caleb closed the door behind him.

“Thomas Kincaid. Gideon Halloway. Silas Langford. Everett Devereaux,” Caleb said, each name heavy with consequence. “Tell me why.”

She studied him like she was weighing whether he deserved an answer.

Then she said, softly, “Because men like them believe the world is theirs by right.”

“That’s not a motive,” Caleb replied. “That’s a philosophy.”

“Yes,” she said. “And philosophy is what built the world you patrol.”

Caleb’s hands curled into fists, then relaxed. He forced his voice to stay even.

“You killed them,” he said.

She didn’t deny it. She didn’t confess either. She simply said, “I ended them.”

Caleb’s jaw tightened. “And their wives? Their children? What did they do to you?”

For the first time, something flickered across her face. Not remorse exactly, but acknowledgment of weight.

“I didn’t choose the battlefield,” she said. “I was born into it. I was sold into it. Every day I lived was a war where I was expected to lose quietly.”

Caleb stepped closer, careful. “You carved MERCY into Kincaid’s back. Why?”

Her eyes met his, steady and dark. “Because they loved to speak of mercy when it cost them nothing.”

Caleb felt anger flare, not only at her, but at the system that had made this conversation possible.

“You know what they’ll do if they catch you,” he said.

“They’ve been doing it,” she replied. “To everyone who looks like me. Catching is just another word for owning.”

Caleb’s throat tightened. He thought of Nora Bell trembling with fear. He thought of the enslaved lined up in yards like livestock. He thought of the planters who demanded justice while calling their own crimes “tradition.”

And still, he thought of the bodies.

He leaned in and said the truth, because it was the only thing he had left to offer.

“I can’t pretend this is righteous,” he said. “But I also can’t pretend it came from nowhere.”

The woman’s voice softened, almost weary. “Do you know what I learned watching men like them?” she asked. “Power is loud until you touch their shame. Then it becomes a cage.”

Caleb’s pulse hammered. “What do you want now?”

She looked down at her hands, then back up, as if choosing a door.

“I want the world to remember that you built a prison, and a woman you called property learned how to pick the lock.”

She stood, and her voice stayed quiet, but the air in the room tightened around it like a noose. “You taught me to be owned,” she said. “I learned to become a storm.”

Caleb felt the weight of that line settle into his bones, not because it was poetic, but because it was true in a way the district would never forgive.

He took a breath. “If I let you walk out of here, I become part of it.”

“If you arrest me,” she answered, “you become part of it too. You just get to call it law.”

Silence filled the room, thick as humidity before lightning.

Caleb made a decision then, not clean, not heroic, but human.

“Leave Georgia,” he said. “Tonight. Don’t come back. Don’t make more bodies to prove what the living already know if they’re honest.”

Her gaze held his. “And you?”

“I’ll do what I can with what I’ve learned,” Caleb said. “Quietly. Before they bury me with the rest of the inconvenient.”

She hesitated, then nodded once, like sealing a contract neither of them could write down safely.

When she moved toward the door, Caleb stepped aside.

He did not touch her. He did not bless her. He did not absolve her.

He simply let her pass, because sometimes the only mercy left in a violent world is refusing to add to it.

What Remained After the River Went Quiet

The district never got its neat ending.

Officially, the cases were “unresolved.” Unofficially, the planters told themselves it had been outsiders, criminals, abolitionist agitators, anyone but what the truth suggested: that the system had produced a strategist inside its own walls.

Caleb filed reports that said less than he knew. He pursued leads that kept the powerful satisfied without delivering a scapegoat. He watched the governor’s office seal documents like coffins.

And he did one more thing, small enough to survive scrutiny.

Using fragments pulled from Langford’s journal, Caleb forced a quiet transfer of three children, born to enslaved women and sold away, back to families who had been searching for them for years. He did it without announcing it as justice, because in Georgia, justice was a word the powerful liked to carve into other people.

Years later, in 1856, after Caleb’s hair began to grey and his hands began to ache in the cold, a letter arrived at the courthouse with no return address.

Inside was a single page, written in careful script.

It spoke of a northern city where Black children learned to read in a small room above a tailor shop. It spoke of a woman who taught them letters like they were keys. It spoke, briefly, of regret that wasn’t repentance, of the complicated ache of knowing that even wars against monsters leave rubble where innocents once stood.

The letter ended with an initial only.

L.

Caleb folded the page and locked it in the same drawer where he kept things the district couldn’t handle: truths too sharp for polite society.

He never told anyone what he had seen in that boarding house. He never confessed his own choice, because confession wasn’t always a path to redemption. Sometimes it was just a way to hand your life to people who would use it as proof that the world must stay the same.

Instead, Caleb lived with the story the way the river lived with its secrets: carrying them forward, sometimes revealing a piece, never offering the whole.

And somewhere beyond Georgia’s marshes, beyond the reach of the men who believed themselves masters, a woman with many names stood in front of a chalkboard and wrote a word that used to be carved into skin.

Not as a punishment.

Not as a threat.

But as a lesson.

Mercy.

THE END

News

CEO Used Sign Language With a Single Dad “Help Me—He Has a Weapon ”

Inside it was a contract dressed up like business. Forged board signatures. Transfer clauses that would activate immediately. A shell…

My Brother Called: “Mom Died Last Night. I Inherited Everything. You Get Nothing.” Then I Smiled…

My name is Douglas Harrison. I’m sixty-four, a retired civil engineer, the kind who spent forty years designing bridges and…

I got pregnant when I was in Grade 10. My parents looked at me coldly and said, “You brought shame to this family. From now on, we are no longer our children.”

Her eyes met mine. And the world tilted. It wasn’t just that she was pretty or that she had the…

My Husband Hide Me At The Party . Then the CEO Found Me And Said: “I’ve Been Searching For You…

A server moved through the crowd, balancing a tray of hors d’oeuvres. Sarah lifted her glass slightly, just enough to…

“Mom Was Too Sick to Come, So I Came Instead.” – The Day a Little Girl Walked Into a Blind Date—and Changed a Billionaire’s Entire Life

Graham blinked once. His brain reached for the closest script and found nothing but blank pages. He rose halfway from…

HER FATHER MARRIED HER TO A BEGGAR BECAUSE SHE WAS BORN BLIND AND THIS HAPPENED

Zainab had never seen the world, but she could feel its cruelty with every breath she took. She was born…

End of content

No more pages to load