The wind didn’t just blow in late winter along the Yellowstone. It worked. It worried the cottonwoods until they creaked like tired bones, shoved snow into seams and corners, and tested every hinge as if the land itself were trying to pry open whatever people had nailed shut.

Inside the cabin, Beatrice “Bea” Jamison fed the stove the last broken chair leg and watched the flame take it the way a hungry dog takes scraps. Quick. Without gratitude. Like it was owed.

She stood with her hands on her hips, the heat close enough to sting her shins, and tried not to think about how quiet a house could get when it had been emptied by years.

Five winters since Edward had died, stiff with pneumonia before the creek even froze. Five winters since the boys had ridden east, one promising he’d return after a season, the other promising he’d write once he reached California. Promises, it turned out, could be lighter than snow. They blew away.

Last spring, the bank had taken the south pasture. Half the land that had once felt like a future. Now, Bea measured her days by what she could keep from falling apart.

She was fifty-one, and the ache in her joints felt older than that.

She had not expected another knock at her door after sundown. Not out here. Not in a storm that made even wolves think twice.

When it came, her body moved before her mind did. Rifle lifted from the corner. Fingers steady because panic wouldn’t keep anyone alive.

She yanked the door open.

Snow rushed in like an insult.

On her porch stood a tall cowboy with a coat stitched in two places and patched in four more, hat set crooked as if it had taken a punch and refused to straighten. His beard wore a crust of ice. In his arms, a child slept, limp with exhaustion, mouth slightly open, cheeks raw from windburn.

The man didn’t reach for a weapon. Didn’t step forward. He just stood there and let the storm climb his shoulders.

“I’m sorry to bother you, ma’am,” he said, voice rough as gravel but careful with each word. “We got caught in it. My horse went down. We just need a place to warm for a bit.”

Bea’s gaze flicked to his hands. Big, cracked, no fancy rings. She looked at his eyes next. Not bright with trouble. Not hungry the way desperate men sometimes looked. Tired. Watchful. The kind of watchful that wasn’t aimed at her, but at the world.

She didn’t recognize him.

That was unusual. Bea knew nearly every soul within twenty miles. The ones who borrowed salt and returned it. The ones who didn’t. The ones who came to church only when a funeral forced them.

“You’re not from around here,” she said.

“No, ma’am.” He adjusted the boy gently, the movement practiced. “We were headed toward Miles City. I was told there’s work there.”

“Name?” Bea asked, rifle still in her hand, barrel angled down but not put away.

“Malden Lark,” he said. “This is my son, Levi.”

The boy made a small sound in his sleep, as if even dreaming was hard work. Malden tightened his hold without waking him.

Bea stared at the child a moment longer than she meant to. She hadn’t felt a small body in her arms in years. Not since the boys were still boys.

Her throat tightened, annoyed at itself.

She stepped back from the doorway. “Come in. Fire’s low, but it’s better than dying on my porch.”

Malden didn’t sigh in relief. Didn’t act like a man who had been granted mercy. He only nodded once, grateful in a way that did not ask for more than offered, and stepped inside carefully, wiping his boots on the threshold like he feared disrespect might get him thrown back into the snow.

Bea shut the door hard against the wind and fed the stove another stick of whatever would burn.

“Sit,” she told him. “Both of you look half-frozen. I’ll get something warm.”

She had soup, if you could call it that. Parsnip boiled thin with salt, the last of the winter roots stretched into something that pretended to be a meal.

She poured it into tin cups. Two of them.

Only two, her mind insisted. You don’t know him. You don’t owe him more.

But the third cup sat there on the shelf, dented and lonely, and she couldn’t bear to leave it that way.

So she poured a little into it too. Not much. Enough to make the stove-light shine on the surface.

Levi stirred when Malden lowered him near the heat. The boy’s eyes blinked open, slow and confused. He looked around like the world might bite.

“Is this a hotel, Pa?” he whispered.

Malden smiled down at him, and for a moment his face softened like snow melting. “No, son. A kind lady let us in.”

Bea handed them the cups. The boy drank like it was gold.

She sat across from them. Her chair complained under her weight. The cabin smelled of woodsmoke and old blankets and the honest loneliness of a place lived in by one person too long.

“You don’t have a wife?” Bea asked, blunt because softness invited questions, and she was not in the habit of inviting anything.

Malden’s eyes dropped to the tin cup in his hand. “She passed two years back. Fever caught her fast. After that… it was just me and Levi.”

Bea nodded once. “Mine died seven years ago. Pneumonia.” She swallowed, remembering the sound of Edward’s breathing when it turned ragged. “I buried him behind the barn.”

They went quiet then, the kind of quiet that didn’t feel like punishment. The fire popped. The wind whistled through the cracks of the window frame, trying to wedge itself into their lives.

“You live out here alone?” Malden asked.

“I do.” Bea’s voice had no apology in it. “Had two sons grown. One went to St. Paul. The other chased gold down to California. Neither wrote back right.”

Malden’s jaw tightened, not at her, but at the injustice of it. He didn’t say anything. He didn’t have to.

Levi’s eyelids drooped. He curled near the stove like a pup and fell asleep again, his small fingers still clutching the cup.

Malden draped his coat over the boy’s shoulders, then leaned back against the wall as if he didn’t trust furniture to hold him.

“You’re strong,” he said after a while, voice low. “Living out here alone.”

Bea gave a dry laugh. “I’m old and stubborn. That ain’t the same as strong.”

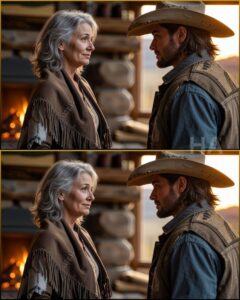

He looked at her then, and it wasn’t the quick glance people gave a woman past her youth, already turning away as if she were a fencepost. It was the kind of look that said he was actually seeing her. The silver in her hair. The lines at her mouth. The way her hands kept busy even when she sat still.

“I don’t think you’re old,” he said.

Bea lifted one eyebrow. “How old are you, Mr. Lark?”

“Thirty-five.”

She let out a sharp breath that was almost a laugh. “You’re a boy.”

“I haven’t been a boy since I was twelve,” he said, not angry, just honest. “Digging graves for cholera victims in Kansas.”

The words settled between them with a weight that made the fire seem smaller.

Bea looked away. She’d learned that truth like that didn’t need to be poked at. It needed to be respected. Like a bruise.

“You can sleep here tonight,” she said, standing. “But come morning, you’ll need to move on. I don’t have much.”

“Understood.” Malden hesitated, then added, “But if you’d let me… tomorrow I could fix that barn door swinging in the wind. Fence too. I saw it coming up.”

Bea crossed her arms. “You offering to work for a place to stay?”

“I’m offering to help,” he corrected softly.

She studied him again. The straightness in his spine. The seriousness, like he’d been carved that way. And the way he looked at her like she wasn’t invisible.

“You can stay two days,” she said. “No more.”

He nodded. “Fair enough.”

By the end of the second day, the barn door no longer groaned like a dying animal. Malden replaced the worst hinge, drove nails clean and true, and braced the frame with a strip of oak he’d split himself. He mended the fence the way a man mends something he plans to see again: not quick, not sloppy, but right.

Levi, meanwhile, had attached himself to Bea as if the cabin had magnets and she was the strongest pull.

He followed her while she gathered eggs, asking why hens laid some days and not others. He followed her while she split kindling, asking why her hands had scars. He followed her while she chopped onions, asking why grown-ups didn’t cry when their eyes stung.

“You don’t cry because you don’t want to,” Bea told him once, wiping her cheek in irritation.

Levi peered up at her. “My ma cried.”

Bea’s throat tightened again. It was becoming a nuisance.

“Well,” she said, “your ma was allowed.”

Malden overheard that and didn’t smile, but his eyes warmed the tiniest bit, as if Bea had given his dead wife a place in the room without making it a shrine.

On the morning of the third day, Malden came in from chopping wood with snow crusted in his beard. He shook it off, set the axe by the door, and stood a moment like he was bracing himself for something heavier than work.

“I know you told me to leave today,” he said.

Bea kept stirring the pot as if his words were wind. “Mm.”

“But truth is,” he continued, voice steady, “I don’t want to.”

Her spoon stopped.

Silence held them.

The only sound was Levi humming to himself on the rug by the stove, rolling a wooden hoop with a stick like it was the finest toy in the territory.

Bea turned slowly. “Why?”

Malden’s gaze didn’t drop to the floor the way men’s often did when they asked for something. He didn’t look at her like she was a favor.

“Because you’re the first person in a long time who makes this world feel less empty,” he said.

Bea’s chest tightened hard enough to hurt. She told herself it was the smoke.

“You’re too young for me,” she said, because that was the sensible wall. The sturdy wall. The wall that kept a woman from being foolish.

He stepped closer, but not so close she had to move. He respected distance the way he respected tools: careful, aware of the harm he could do if he used it wrong.

“You’re not too old for love,” he said.

Bea looked away, irritated with her own eyes for wanting to sting.

“You don’t know me, Malden.”

“I know enough,” he replied gently. “And I’d like to know more.”

His hand grazed hers, just the brush of skin, like a question asked without pressure.

“I’ve waited my whole life for someone like you,” he said, low and certain. “Someone who knows how to survive. Who doesn’t flinch at silence. Someone who sees me.”

Bea’s throat worked. Her body remembered being looked at with hunger once, long ago, when Edward was young enough to laugh easily. But Malden’s look wasn’t hunger. It was recognition.

Levi came charging in then, holding an egg in both hands like it was treasure.

“Miss Bea!” he crowed. “The hen laid one!”

Bea took it carefully, her fingers brushing his. A warm, ridiculous ache filled her chest, the kind that felt like both grief and hope sharing the same chair.

She looked at Malden.

He waited. Patient as a man who’d slept in too many storms.

“Maybe you two should stay,” she said softly.

Malden’s eyes met hers. “We’d like that.”

And just like that, the cabin’s quiet changed shape. It was no longer empty. It was held.

Spring didn’t arrive all at once. It crept in on its belly, drip by drip from the eaves, loosening winter’s nails.

The creek ran faster. Mud replaced snow in the yard, the kind of mud that clung to boots like it was lonely too.

Bea felt it in her knees, the slow shift of earth trying to remember softness. She stood by the root cellar, lifting the hatch with a grunt, selecting potatoes that hadn’t sprouted too badly.

Behind her, the steady rhythm of an axe sounded from near the shed.

“Those won’t keep much longer,” Malden called as he approached, wiping his hands on his shirt.

“They’ll keep long enough,” Bea replied, setting the basket on her hip. “I’ll boil ’em with onions.”

Malden’s gait was slower than usual. Bea narrowed her eyes.

“You limping?”

He gave a slight nod, like admitting weakness was a tax he hated paying. “Pulled something yesterday lifting the water barrel. Just needs rest.”

“You should have said something.”

“I didn’t want to fuss.”

Bea stopped at the door and looked him dead on. “This isn’t the trail. You don’t need to grit your teeth and keep going. Not here.”

His eyes held hers. Something in his jaw unclenched.

“I know,” he said quietly.

Inside, Levi sat cross-legged at the table, carving a block of pine with a penknife. His tongue stuck out in concentration.

“It’s a bird,” he announced proudly. “Like the ones in the cottonwoods.”

“You’re getting the shape right,” Bea said, leaning to inspect it. “Curve the wings more.”

Levi nodded solemnly and went back to work like a craftsman.

That evening, Malden sat in the rocker by the window with his leg wrapped in a cloth soaked from the creek. Bea brewed dried mint and set the cup beside him.

“Drink it before bed,” she ordered.

He lifted the cup, sniffed it. “Does it help?”

“My mother swore by it for sore joints,” Bea said. “Said it calmed the spirit.”

Malden’s fingers brushed hers as he took it. His voice was quiet. “Your hands are warm.”

“They’ve been near the stove,” Bea muttered, irritated at herself for blushing like a girl.

“No,” he said, and there was something tender in the correction. “Warm in a way I haven’t known in a long while.”

Bea sat across from him and began knitting socks from gray wool, needles clicking like a steady metronome.

Malden watched her hands. “You always do things exact.”

“There’s no point doing something halfway.”

He leaned forward, elbows on his knees. “That how you learned to live too?”

Bea didn’t look up. “I learned to live by watching everything fall apart and still waking the next morning.”

The room held that truth without arguing.

“I used to think if I just kept moving, I wouldn’t feel the cracks,” Malden admitted. “But they follow you.”

“They do,” Bea agreed.

Levi had fallen asleep in his chair, the half-carved bird resting in his lap, head tipped back, mouth open.

Malden’s gaze softened at the sight. “Being here… it’s the first time I’ve stopped long enough to notice how tired I am.”

Bea set her knitting down, stood, and knelt to check the wrap around his leg. Her touch was practical, but not cold. She adjusted the cloth, then rested her palm over his shin, steady as a promise.

“You don’t have to earn your place here,” she said. “It’s already yours.”

Malden’s hand covered hers, rough and warm. “I want to build something with you,” he said. “Not just survive beside you. A life. One that grows.”

Bea looked up at him in the firelight. The lines in his face weren’t the lines of a boy. They were the lines of a man who’d had to become careful to stay alive.

“Then we’ll sew it slow,” she said. “Nothing rushed. Nothing borrowed.”

His thumb brushed hers. “I’ve waited for something real. I’ll wait as long as it takes.”

Bea helped him to his feet and guided him to the bedroom, and when they lay down, there were no grand speeches, no theatrical kisses. Just his hand finding hers beneath the quilt. Fingers lacing slow and certain.

Outside, the wind didn’t rise again.

And in the warmth of the room, the quiet wasn’t empty.

It was full.

Town arrived in their lives the way it always did: unavoidable.

They hitched Bea’s mule to the wagon one morning and rode in together, Levi bundled in a blanket in the back with a tin lunch pail on his knees.

Bea wore her brown shawl with the repaired fringe. Malden had shaved clean, revealing a mouth that curved easier now, as if the muscles had forgotten they were allowed to.

At the mercantile, Malden traded pelts for flour and kerosene. Bea picked out a bolt of calico dotted with faded blue flowers, scolding herself for wanting something pretty.

At the post office, the clerk handed Bea a letter addressed in unfamiliar script.

Bea stared at it as if paper could carry a bullet.

She slipped it into her pocket unopened.

Outside, Malden caught her expression. “Bad news?”

“Not sure yet,” she said. “But it won’t change anything here.”

She meant it. She wanted to mean it.

They stopped at the blacksmith’s shop before heading home. The smith handed Malden a set of iron hinges he’d ordered for a garden gate.

Bea hadn’t asked for a gate, but she wasn’t surprised either. Malden was the kind of man who fixed problems before they became disasters.

That evening, Bea opened the letter by lamplight while Malden sharpened a knife at the table and Levi colored the margins of an old newspaper with charcoal.

It was from her eldest son.

He wrote that he’d married a woman in Minnesota, that he had two daughters, that he worked at a printing press. He hoped she was well.

There was no return address.

Bea read it twice, then folded it so neatly it looked untouched, and tucked it into her ledger where Edward’s old entries lived.

Her fingers trembled once. Just once.

Malden didn’t ask. He didn’t push. He only reached across the table and pulled her hand into his lap, holding it there like he was anchoring her.

Bea stared at the flame in the lamp and let herself breathe.

“Do you want to go after him?” Malden asked finally, voice careful.

Bea’s jaw shifted. “No.”

“You sure?”

“Letters without an address aren’t invitations,” Bea said. The bitterness surprised her with its sharpness. “It’s a man easing his conscience without giving me the power to answer.”

Malden nodded slowly, absorbing that.

Levi looked up, eyes wide. “Your son didn’t come home?”

Bea’s throat tightened, but she forced her voice steady. “No, honey. He didn’t.”

Levi scooted off his chair and walked around the table. He placed his small hand on Bea’s forearm like he’d seen adults do.

“Then you can have me,” he said matter-of-factly. “I’m good at being here.”

Bea blinked hard. Malden’s eyes went bright, but he looked down fast, as if emotion were something that could spill and make a mess.

Bea rested her hand on Levi’s head. “I think,” she managed, “I already do.”

By early summer, the garden bloomed with beans and squash and the beginnings of corn. Malden added a second row of fencing and built a bench beneath the cottonwoods where the three of them sat after supper, passing a harmonica back and forth and taking turns trying to wrestle music out of it.

Levi grew taller, shoulders beginning to square, laughter coming easier. Malden taught him fishing knots and how to shoe a mule. Bea taught him how to read the sky before a storm, and how to tell good seed from bad by the feel of it between his fingers.

Sometimes, Bea forgot her own age until she caught her reflection in a kettle and saw the silver and the lines and the truth that time had not stopped just because love had returned.

And that was when fear would creep in.

One afternoon, Bea came back from the creek and found Malden standing at the edge of the field, still as a fencepost, staring toward the south pasture the bank had taken. Two riders approached, slow and deliberate.

Bea’s stomach dropped. Men didn’t come out this far unless they wanted something.

Malden’s hand rested on the fence rail, but his shoulders tightened in a way Bea recognized now: the old posture of someone waiting for the next blow.

The riders stopped near the gate.

One of them was the bank agent Bea had dealt with last spring, a thin man with a hat too clean and eyes too pleased with himself.

The other was a stranger in a dark coat, city-cut, boots polished. He looked wrong against the land. Like a crow perched in a church window.

“Well,” the bank agent called, voice carrying. “Mrs. Jamison. Didn’t expect to find company.”

Bea stepped forward, chin lifted. “What do you want?”

The city man’s gaze slid to Malden. His eyes sharpened, then narrowed, as if recognition had landed like a bad taste.

“You,” the city man said, pointing. “You’re Malden Lark.”

Malden didn’t move. “Depends who’s asking.”

The man smiled without warmth. “Someone you owe.”

Bea’s heart thudded. Levi was behind her, clutching her skirt. She felt it, the way fear could travel from a child into a woman’s bones like cold.

The bank agent cleared his throat, enjoying himself. “We’re here about the north ridge. There’s been… paperwork. A reconsideration.”

Bea’s mouth went dry. “The north ridge isn’t mortgaged.”

“Not yet,” the agent said smoothly. “But there are new claims. Old debts. The bank can’t ignore them.”

Bea looked at Malden. “What is this?”

Malden’s jaw flexed. “It’s my past catching up,” he said quietly.

The city man stepped closer, eyes hard. “You thought you could hide out here with a widow and a sob story. You ran off with money that wasn’t yours.”

Malden’s voice stayed level, but Bea felt the steel beneath it. “I didn’t run. I survived.”

The bank agent lifted a paper, waving it like a flag. “A lien can be placed if the claim is verified. Might mean seizure. Might mean… well. You know how it goes.”

Bea’s vision narrowed. Not again. Not after she’d started letting herself breathe. Not after she’d started letting the house feel like a home.

She stepped forward until she was close enough that the bank agent had to look up at her. “You don’t get to threaten my land because you’re bored,” she said, voice low and sharp. “Say what you mean.”

The city man’s eyes flicked to her, dismissive. “Ma’am, this is between men.”

Bea smiled, and it wasn’t kind. “Everything that happens on my land is between me and whoever dares step on it.”

Malden’s hand touched her elbow, gentle. “Bea…”

“No,” she said, not looking at him. “Tell me the truth.”

Malden exhaled slowly. “When Levi was a baby, we lived near Dodge. A rancher there hired me. Paid me in scrip, kept the books crooked. When my wife got sick, I begged for an advance. He laughed. Said I could pay with my hands.”

Bea felt her stomach twist.

“I didn’t,” Malden continued, voice like stone. “I took what was owed and left. He called it theft. I called it a man trying to keep his family alive.”

The city man sneered. “You stole from Silas Ketter.”

Malden’s eyes flicked up, cold. “Silas Ketter stole from every man he hired.”

The bank agent shifted, uneasy note creeping in now that the story wasn’t as simple as villain and hero. “The claim says there’s still money owed. Interest. Damages.”

Bea looked at Levi, at the child pressed against her, eyes wide as the sky. She felt something in her chest go still and hard.

“Get off my land,” she said to the riders.

The bank agent laughed, trying to reclaim control. “Ma’am, you don’t understand. If we file the—”

Bea raised the rifle she hadn’t even realized she’d brought from the cabin. Not aimed at anyone’s chest. Just lifted enough that the sunlight caught the barrel.

“I understand perfectly,” Bea said. “You have paper. I have property. And I have the right to defend it.”

The city man’s face tightened. “You’d shoot over a hired hand?”

Bea’s eyes didn’t blink. “I’d shoot over my family.”

The word landed in the air like a bell.

Malden’s breath caught. Levi made a small sound, half-sob, half-relief.

The bank agent’s smile drained. He muttered something, tugged his reins. “We’ll be back with law.”

“Bring it,” Bea said. “And bring witnesses. I want everyone to hear the kind of men you work for.”

The riders turned. The bank agent’s horse trotted away fast, as if the land itself had offended him. The city man lingered half a second longer, eyes locked on Malden.

“This ain’t finished,” he hissed.

Malden didn’t flinch. “It never was.”

When they were gone, the field was suddenly too quiet.

Bea lowered the rifle slowly. Her hands trembled now, the aftershock.

Malden stepped close. “Bea… I didn’t mean for—”

She turned on him, eyes blazing not with anger, but with fear. “You think I invited easy into my home?” she snapped. “You think I don’t know what it costs when the world decides it wants what little you’ve got?”

Malden’s face tightened, pain flickering. “I’m sorry.”

Bea’s throat worked. “I’m not afraid of trouble,” she said, voice breaking. “I’m afraid of losing you.”

Malden’s eyes softened, and he lifted his hands like he was approaching a skittish animal. He didn’t grab her. He waited until she leaned into him.

“I didn’t come here to ruin you,” he said, low. “I came here because I was tired of running and because… because you made a place where I could stop.”

Bea pressed her forehead against his chest and let herself breathe in the smell of him: sweat, soap, woodsmoke. Real things.

Levi hugged her waist tight, his small arms fierce.

“I don’t want you to go,” he whispered.

Malden crouched and pulled Levi into his other arm. “I’m not going,” he promised. Then he looked at Bea. “Not unless you tell me to.”

Bea swallowed hard, tasting the old loneliness she’d lived on like thin soup. “I won’t,” she said. “But we’re not pretending anymore. If they come back… we fight smart.”

Malden nodded once. “Then we fight smart.”

They rode into town two days later, not because they wanted to, but because that was where paper got turned into truth.

Bea wore her best dress, the one she’d saved for funerals and church, which told you everything about her idea of “best.” Malden wore his clean shirt, patched at the elbow, and his hat straight for once.

Levi sat between them in the wagon seat, small hands folded like he was bracing.

At the courthouse, the clerk tried to wave them off until Bea said, clear and loud, “I want the judge.”

People turned. They always did when a woman demanded something.

Judge Harland Pierce was an old man with a face like weathered oak. He listened without smiling, eyes flicking between Bea’s hard gaze and Malden’s steady one.

“You’re telling me,” the judge said slowly, “that a rancher in Kansas is reaching into Montana to take land from a widow because a hired hand took wages he claims were owed?”

“Yes,” Bea said.

“And you,” the judge said to Malden, “you admit you took money.”

“I took what was owed,” Malden replied.

The judge tapped his pen against the desk. “Silas Ketter’s a man with a long shadow,” he muttered, almost to himself. Then louder: “Do you have proof your employer withheld wages?”

Malden hesitated. “Not paper.”

Bea leaned forward. “Then we get people,” she said. “We get men who worked for him. We get the truth.”

The judge watched her a moment. Then his mouth twitched like he was trying not to respect her. “All right,” he said. “I’ll delay any action on her property until a hearing. But if Ketter’s men show up with a marshal—”

“They won’t,” Bea cut in.

The judge raised an eyebrow. “And why’s that?”

Because Bea had already done what lonely women learned to do when the world tried to swallow them: she’d built a web of small loyalties.

She’d traded eggs with the mercantile owner. She’d mended the preacher’s wife’s shawl. She’d helped the midwife with herbs when the last baby came breech.

And she’d told every one of them, in a voice as calm as ice: If the bank comes for my land, they’ll come for yours next.

Now she looked the judge in the eye. “Because people are watching.”

The judge stared, then exhaled. “You’ve got a spine like a railroad spike,” he said.

Bea didn’t smile. “I had to.”

Summer held its breath.

No riders came in those weeks, but the threat lived like a thorn under the skin.

Malden worked harder, not because he thought sweat would pay off danger, but because building was what he did when fear tried to eat him alive. He reinforced the barn. He repaired the roof. He built a proper gate for the garden, the hinges iron and honest.

Bea, meanwhile, began teaching him letters at the table in the evenings.

His hand was big and awkward around the pencil, but he tried with the stubbornness of a man who’d dug graves at twelve and decided he wouldn’t be defeated by ink.

“That’s an A,” Bea told him patiently.

Malden squinted. “Looks like a tent.”

“Everything looks like something else until you learn its name,” Bea said, and surprised herself with how much that sentence belonged to more than the alphabet.

Levi learned faster, of course. Children always did. He sat between them, reading words aloud like small victories.

One evening, after Levi fell asleep, Malden stared at the page a long time, then looked up at Bea with something raw in his face.

“I never knew what it was to be tended,” he said quietly. “Not like this.”

Bea’s throat tightened. She reached across the table and touched his knuckles, rough and warm. “You’re not a burden,” she said. “You’re a blessing I didn’t ask for but won’t give back.”

Malden’s eyes went bright. He blinked it away fast, as if tears were a luxury.

Outside, the wind moved through the cottonwoods, softer now, like it had learned to behave.

The hearing came in late August, and with it, Silas Ketter’s shadow.

He did not come himself. Men like him rarely did. He sent the city man in the dark coat, and two witnesses who looked like they’d been paid to remember things wrong.

Bea came with her witnesses: an old ranch hand who’d worked for Ketter and still carried a limp from being kicked for asking about wages; a woman who’d cooked for Ketter’s crew and had seen him dock men’s pay for “attitude”; a preacher who had once traveled through Dodge and heard the stories.

The courtroom smelled of sweat and paper. Levi sat on the bench beside Bea, legs swinging, face solemn like a little judge of his own.

The city man spoke first, smooth and cruel. “This Malden Lark is a thief. He stole money. He fled. Now he hides behind a widow’s skirts.”

Bea rose so fast her chair scraped. “He hides behind nothing,” she snapped. “He stands in front of me. Like a man.”

The judge banged his gavel once, not angry, more like reminding everyone that he was still in charge. “Mrs. Jamison, sit.”

Bea sat, jaw tight.

Malden took the stand. He told the truth without decoration. The withheld wages. The sick wife. The baby. The choice between starving honest and surviving wrong.

Then Bea’s witnesses spoke. The limp ranch hand. The cook. The preacher.

Each story stacked on the next until Silas Ketter’s “honor” looked like rotten wood painted over.

The judge listened, eyes narrowing, then turned to the bank agent. “You were willing to seize a widow’s land over a claim from a man with a reputation like this?”

The bank agent’s face turned the color of curdled milk. “We… we had paperwork.”

“Paper can be a lie,” the judge snapped. “Especially when men with money write it.”

Bea’s heart pounded so hard she could feel it in her fingertips.

At last, the judge leaned back and exhaled. “Claim dismissed,” he said. “No lien. No seizure. And I advise Mr. Ketter… to keep his reach on his own side of the country.”

The city man’s face tightened, but he didn’t speak. He gathered his papers and left like a man swallowing humiliation.

Bea didn’t exhale until the courtroom emptied.

Levi grabbed her hand. “We won,” he whispered, eyes shining.

Bea looked down at him and felt a sudden, dizzy realization: it wasn’t just that they had kept the land.

They had kept the life they’d built on it.

Outside the courthouse, Malden paused, turning to Bea. His gaze was steady, serious.

“I’m sorry my past tried to steal from you,” he said.

Bea looked at him, really looked, and she saw the boy he’d been digging graves, the man he’d become carrying a child through storms, and the person he was now, standing beside her like he belonged.

“You didn’t steal from me,” she said, voice thick. “You came to me.”

Malden’s hands flexed at his sides, like he didn’t know what to do with gratitude.

Bea stepped closer. “I told you once you were too young,” she murmured. “I was wrong.”

Malden’s eyes softened. “And you told me once you were too old.”

Bea’s mouth curved, small and fierce. “I was wrong about that too.”

That evening, when they returned home, Bea lit a lantern and set it in the window.

Not to guide anyone back who had left.

Not to beg for a letter with an address.

But to mark the cabin as full.

Malden built the garden gate the next day and hung it straight. Levi carved his bird until it looked like it might fly. Bea wrote in her ledger, careful as prayer:

Late summer 1883. We kept what was ours. We did it together.

One evening as the sun dipped low, Malden knelt in the garden with dirt on his palms and a ring in his hand.

It wasn’t gold. It was a simple band made from riverstone smoothed and set into carved wood, crafted with the same care he gave to every small thing in her life.

“If I ask you to marry me,” he said, voice steady, “will it change the way we are?”

Bea stood over him, wiping her hands on her apron. She thought of winters that had tried to break her. She thought of silence that had almost convinced her it was all she deserved.

“Only if you stop listening when I speak,” she said.

“I won’t,” Malden promised.

Bea’s throat tightened. She nodded once, because some answers didn’t need speeches.

“Yes, Malden Lark,” she said. “You can ask me.”

He rose and slipped the ring on her finger. It fit snug, like it had always belonged there.

They married beneath the cottonwoods three weeks later, with Levi standing between them holding a bouquet of wild yarrow, proud as a prince.

There were no guests, no preacher, no grand feast. Just promises spoken aloud and sealed with earth under their nails and laughter on the wind.

That night, Bea lay in bed beside Malden and listened to Levi’s breathing from the cot by the pantry. A steady sound. A living sound.

Malden’s hand found hers under the quilt.

“You sure?” he whispered, careful as ever.

Bea turned her face toward him. The darkness could not hide her smile.

“I spent too long thinking love was for younger people,” she said softly. “Turns out love is for the living.”

Malden kissed her knuckles, reverent. “I’ve waited my whole life for you.”

Bea’s eyes stung again, but this time she let them.

Outside, the wind moved through the cottonwoods, not howling now, but humming, like the land itself had decided to soften.

And in that cabin by the Yellowstone, the quiet wasn’t a punishment anymore.

It was peace.

THE END

News

THE DUKE PAID $10 FOR A “SILENT” BRIDE — HE GASPED WHEN SHE SPOKE 7 LANGUAGES

Rain didn’t fall in polite little drops that Tuesday. It came down like it had a grudge, drumming on the…

STRUGGLING WIDOWER MEETS “TOO FAT” BRIDE ABANDONED AT RAILROAD STATION, MARRIES HER ON THE SPOT

The wind had teeth that evening, snapping at the porch rails and tugging at the thin curtains like it wanted…

MAIL-ORDER BRIDE REJECTED FOR BEING “TOO FAT” UNTIL ANOTHER MAN SHOWED HER TRUE LOVE

In the winter, the world still felt unfinished. Out on the far edge of the Dakota Territory, where the sky…

SHE WAS REJECTED FOR HER CURVES — BUT THAT NIGHT, A LONELY RANCHER COULDN’T RESIST

Dry Hollow, Colorado Territory, Winter, looked like the kind of place the world forgot on purpose. The wind came in…

MAIL-ORDER BRIDE WAS REJECTED FOR BEING “ALREADY PREGNANT” UNTIL ONE MAN BECAME HER CHILD’S FATHER

The train arrived like an animal that had run too far on too little mercy. Steel screamed. Brakes shrieked. The…

A POOR GIRL LET A MAN AND HIS DAUGHTER STAY FOR ONE NIGHT, NOT KNOWING HE WAS A MILLIONAIRE COWBOY

The first thing Emma Caldwell heard was breath. Not her own. Not the hiss of wind pushing powdery snow off…

End of content

No more pages to load