Montana Territory, spring, had a way of making people feel temporary.

Red Bluff was barely a town, more a stubborn smudge of boardwalk and smoke pinned to the edge of the trail. Pines began where the last building ended, their roots punching through hard earth like knuckles. Dust hung in the air as if it had forgotten how to fall. The cook fires never rose high, just drifted low and lazy, curling around boots and wagon wheels, finding every seam in a man’s clothes and living there like a second skin.

It smelled of horses sweat, old tobacco, and the sour fear of men who’d come too far to admit they’d made a mistake.

On the edge of town, someone had hammered together a platform from planks nailed to wagon crates. It was crooked, rough, and loud underfoot, like it resented being asked to serve anything as delicate as a human decision.

A crowd gathered in front of it, men with tired boots and hollower hearts. They came to trade livestock and tools, and when the trades ran out, to trade jokes. At the bitter end, they traded something else.

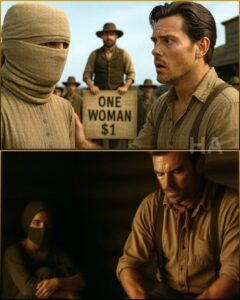

A woman stood barefoot on the platform.

Her ankles were kissed with trail dust. Her wrists were bound so tightly the rope had printed its anger into her skin. And over her head and mouth, rough cloth had been swaddled and knotted, torn from some forgotten sack and sun-bleached into a color that wasn’t quite brown and wasn’t quite gray. Wind had frayed it. Shame had claimed it.

Only her eyes showed: hazel, steady, and distant, like shallow pools that gave nothing back.

“She ain’t spoken since Idaho,” someone said, half like gossip, half like a dare.

The man running the auction wore a weathered burgundy vest and a rusted badge that barely clung to his chest. It was the kind of badge that didn’t shine, only reminded people what it had once meant. He slammed his gavel down on the crate beside him.

“All right,” he barked, voice cutting through the dust. “Last one for the day. Ain’t got no name, ain’t shown her face. Says she’ll work. Says she’ll obey.” He let the words sit there, ugly and useful. “Starting bids… one dollar.”

He swept his eyes over the men.

“Who’s fool enough,” he added with a grin that didn’t reach anything decent in him, “or full enough of whiskey to take on the riddle in a corset?”

Laughter popped like dry twigs in a fire. A ripple moved through the crowd.

“Bet she’s a cactus in disguise!” somebody called.

“Prickly and full of secrets,” another answered, and the laughter grew sharper.

“Or maybe just a sack of laundry with opinions,” a man shouted, and a few hooted like owls who’d learned the sound of cruelty from people.

“Go on,” someone else cackled. “Marry the bedsheet. She’s got about as much to say.”

A few men turned away, done with it already. Others elbowed one another, waiting for someone else to be the first to do the dirty thing so they could pretend they were only watching.

The woman didn’t move. Her bound hands hung loose at her sides, wrists rubbed raw. The sack shifted only with her breathing, quick and shallow but steady. Her fingers clenched and relaxed in small rhythms, controlled but not calm. Like someone counting steps in a dark hallway, remembering where the floorboards creaked.

The auctioneer’s grin faltered.

“She’s no good to anyone if she won’t even speak,” he muttered, but it sounded more like irritation than pity.

Still no one moved.

Then the crowd parted.

A man walked forward, tall coat dusty at the cuffs, boots heavy with dried mud. The brim of his tan trail hat shaded his face, but there was a shape to his shoulders that suggested he’d done more work than talking in his life. One hand was wrapped in leather strips, the kind earned by rope and heat, not accident. He stepped up until he could smell the cheap tobacco in the auctioneer’s breath.

He didn’t speak until he reached the front.

“One dollar,” he said.

The air shifted. Even the laughter seemed to take a step back.

The auctioneer blinked, then tried to laugh it off. “You sure?”

The man’s gaze flicked to the woman. She hadn’t flinched. Hadn’t begged. Hadn’t even offered her eyes as a plea, only as a fact.

“Don’t even want to see what you’re buyin’?” the auctioneer pressed, trying to make sport of it again, like sport could keep the world from judging him.

The man’s jaw tightened once.

“I ain’t buyin’ a face,” he said. “I’m marryin’ a person.”

For a heartbeat, Red Bluff held its breath. The wind, always nosy, went still.

The auctioneer licked his lips. “Name?”

“Luke Thatcher,” the man said, plain as a fence post. “Cowboy. Lives east of Red Bluff.”

The auctioneer scribbled on the ledger and slid a page forward. Luke signed without flourish, the letters hard and practical.

Then the auctioneer turned toward the figure in the sack, voice suddenly performing solemnity.

“You’re now legally wed, miss,” he announced. “Say your name for the record.”

The crowd shifted. A few men leaned in, curious now, like they were waiting for a circus animal to do a trick.

At first there was nothing.

Then behind the cloth, a voice emerged. Dry. Faint. But firm enough to carry.

“Willa Mercer.”

Luke’s hand stilled, just a flicker. His jaw set. His eyes sharpened on her like a dog hearing a whistle only it recognized.

He didn’t ask why.

He didn’t ask how.

He stepped up to the platform, reached gently for her arm, and untied the ropes biting into her wrists. His fingers moved careful, not because he was afraid of her, but because he understood what rough hands had already taken from her.

When he led her down, not a single man jeered. No laughter. No comment.

Only the sound of boots creaking on dry planks and a name that hung in the air like a secret returning home.

The trail leading out of Red Bluff narrowed fast, dust giving way to pine needles and packed earth. Sunlight barely made it through the canopy, and what did came soft and slanted, like it wasn’t sure it was welcome in the woods.

Luke Thatcher walked ahead, boots steady, leading a mule loaded with supplies. Behind him, Willa followed in silence, the sack still covering her head. But her steps were careful, not weak. Her hands, now unbound, stayed clasped in front of her like she wasn’t quite sure what to do with freedom yet.

They walked for over an hour without words. The pines breathed around them, the leather tack creaked, and somewhere a creek murmured as if it had been told to keep its voice down.

Then the woods opened into a clearing carved into the hillside.

There stood a cabin.

Dark cut timber, small but squared to the wind, as if it had been built by someone who didn’t trust the world to stay gentle. A stack of firewood leaned against the wall. Above the doorframe hung a rusted horseshoe, bent and split at one end, like luck had been tested here and chosen to remain anyway. Smoke curled faintly from the chimney.

Luke pushed the door open.

Inside was clean and tight: one room, one cot, a table, a chair, a stove, a basin. The hearth was cold but ready, like it had been waiting for permission to wake.

Luke stepped aside and spoke quietly, the way you talk to a skittish animal or a grieving friend.

“Ain’t no one tellin’ you where to be now,” he said. “That’s yours to decide.”

Willa entered slowly. She didn’t speak. She didn’t reach for anything. She crossed to the far wall, crouched low with her back to the room, and rested her hands on her knees. She stayed facing away, like turning her face toward a man was still an act that cost too much.

Luke didn’t comment. He hung his hat on a hook by the door and moved to the stove. He set kindling, coaxed flame, filled a pot. He added scraps: dried root, a bit of meat, a pinch of leaf. The scent rose slow and warm, smoke and salt and something like spice. The kind of food made for long silence.

He ladled stew into two bowls. One he set gently near her. The other he placed on the table. Then he sat and waited, not watching her, not making her feel like she owed him a performance.

Minutes passed.

Then her voice came muffled through cloth, steady as a nail hammered straight.

“What is this?”

Luke stirred his bowl once. “Meal for the last one standin’.”

A pause. The faint shift of her shoulders.

“I used to make it for myself,” he said, as if answering a question he’d been carrying longer than the stew. “After the war. After long days with no one talkin’.”

He nodded at the second bowl, steam still rising beside him. “Then I started makin’ two. Even when there wasn’t anyone there.”

Willa turned her head slightly, as if the words pulled her the way light pulls a moth.

“I used to set it for my wife,” Luke went on, voice quiet enough that it could have been meant for the fire. “She passed from fever one spring. Quiet and quick. Brave to the end.”

He kept his eyes on the hearth. “I kept settin’ it out. Just to remind myself I made it home again.”

He swallowed once, his throat working like he didn’t enjoy the taste of remembering.

“Now,” he said, “I set it for her. And for you.”

Willa said nothing. Then her hand trembled as she reached for the bowl. She lifted the spoon beneath the sack and ate without removing it, movements small and deliberate. Cautious, but she finished every bite.

Later, while Luke washed the bowls in the tin basin, Willa stayed by the wall, arms around her knees, watching. She hadn’t spoken since that question, but for the first time she wasn’t hiding from the room.

Somewhere in the quiet, something shifted, the way a door shifts when it’s no longer locked.

Night came soft, like it didn’t want to startle them.

Luke didn’t light the lantern. The fire in the hearth was enough, throwing low shadows across the walls. Outside, wind moved through the trees like breath in a sleeping chest, long and old. Willa sat near the far wall, knees drawn beneath her chin. The sack still covered her head, but she hadn’t touched the door. Hadn’t tried to leave.

Luke sat with his elbows on his knees, staring into the coals as if they could teach him what to say. His jaw worked once. Then he reached inside his coat pocket, fingers closing around a small square of cloth.

He didn’t pull it out.

He just held it.

Three winters ago, he’d ridden too far north chasing timber he couldn’t afford to lose. Pride had driven him past safe cut lines. A storm had come down hard, stripping bark from trees and biting bone through wool. He remembered snow packed hard beneath his boots, and then a slip, and then pain, sharp and final.

His leg twisted beneath him. The world turned white and mean.

He’d crawled into a drift, thinking: This is how men vanish. Not with drama, not with last words, just swallowed by weather and forgotten by spring.

But then there were hands. Rough. Fast. Alive.

He’d been dragged, pain lighting his whole body, into blackness. When he opened his eyes again, there was a cave. Ice at the entrance, heat on his face, and something herbal in the air like bitter mercy.

Across from him sat a woman. Her face was veiled in coarse sackcloth drawn tight and knotted at the neck. Only her eyes showed, still and shadowed.

Her coat was patched leather and threadbare wool. Her hands moved quickly as she poured dark liquid into a tin cup.

“You don’t need to know who I am,” she’d said, voice dry with exhaustion, “but I’m not going to let you die.”

He hadn’t been able to talk. Couldn’t. She pressed the cup into his hands.

“Pine bark and dry lichen,” she said. “Drink.”

It burned going down, but it kept his breath from slowing. She wrapped his leg, braced it with hot stones, kept the fire fed. She moved like someone used to being invisible. Quiet. Constant. The kind of presence you only notice when it’s gone.

He remembered fading in and out of fever and pain, cold trying to pull him under. When he woke again, she was gone. The cave was cold but safe. The fire still lit. And beside it, folded with strange care, was a square of cloth stitched with purple flowers in uneven thread.

No larger than a hand.

He’d kept it. Sewn it into the lining of his coat, where even the worst days couldn’t wear it out.

And now, the voice that had spoken on that auction platform, saying “Willa Mercer,” was the same voice that had whispered “Drink” over that tin cup in the snow.

Same rhythm. Same weight. Same stillness.

Luke didn’t need proof. Not after all this time.

He held the cloth in his pocket, fingers tight around it, and made a decision that felt as simple as breathing.

He wouldn’t ask her to admit it. He wouldn’t make her relive what she hadn’t offered.

But he would not let her vanish again.

Morning arrived hesitant, mist hugging the roots of the trees like silver thread.

Willa stepped out alone, crossing the porch past the empty wash basin, past the mule dozing near the post. She moved toward the tall pine at the clearing’s edge, a quiet guardian.

She wore the sack still, but looser now, not choking. Its hem fluttered faintly in the breeze. At the base of the tree she sat, face turned toward the break in the trees where light touched the clearing’s edge.

Then with both hands she reached behind her neck and untied the knot.

The sack slid upward, revealing her nose, her mouth, the curve of her cheek. She let the air touch her skin. It wasn’t defiance. It wasn’t surrender. It was something between, like a bruise beginning to fade.

Behind the cabin, Luke knelt beside a wooden basin, oiling the teeth of his saw. He didn’t move when she came into view. Didn’t look up right away. When he spoke, his voice was quiet, careful as a match in wind.

“Got turned around once,” he said. “Deep winter near Black Ram Ridge.”

His hand passed over the blade. “Broke my leg. Thought that was it.”

Willa didn’t speak. She stared at the moss near her feet like it could anchor her.

“But someone found me,” Luke continued. “Dragged me into a cave. Built a fire. Fed me bitter tea that tasted like bark.”

He set the saw down gently. Looked over, not directly at her face, but near it, as if he didn’t want to corner her with attention.

“She wore a sack over her head,” he said. “Didn’t tell me her name. Hardly said a thing.”

Silence. Not fear. Not guilt. Just the stillness of a truth walking into the room and sitting down.

Then Willa moved.

She pulled the sack the rest of the way off and dropped it in her lap.

Her face was not monstrous. Not ruined. Not the sort of thing the crowd in Red Bluff had tried to pretend it might be to justify their jokes.

But along her left cheek ran a scar. Deep. Curved. Permanent, from temple to jaw, like something had tried to carve the truth out of her and failed.

She lifted her eyes.

“The man who ran the boarding house where I worked,” she said, voice level, “told me I could keep my room if I gave more.”

Her hands gripped the folded sack. Knuckles pale.

“I said no.” A pause, her breath steadying itself like a horse being soothed. “He came at me. I fought back.”

She swallowed. “He slipped. Hit the stove. Didn’t get up.”

Luke didn’t move. Didn’t do the easy thing men did when they wanted to claim a woman’s pain as their own anger. He stood still, letting her story be hers.

“They said I lured him,” Willa went on. “Said I planned it. Said I killed him on purpose.”

Her gaze drifted toward the woods, not seeing trees but something older. “I think someone saw. I remember a shadow near the door.”

Her voice wavered but didn’t break. “A woman in the kitchen.”

She looked down at her hands. “There were no witnesses who spoke. No one who stood up.”

She breathed in, and it sounded like she was swallowing a stone.

“They called me a liar. A temptress. A killer.”

Luke’s shoulders rose and fell once. He remained quiet, giving her room to finish.

“They sold me off to pay his debts,” she said. “Passed me from one hand to another like cattle. Covered my face so no one would see the scar. So they wouldn’t decide what I was worth before I even opened my mouth.”

She looked up at him fully now, eyes sharp but exhausted. “I didn’t ask to be saved. And I didn’t ask to be bought.”

A beat. Then, softer, but no less steady:

“I’m tired of hiding.”

Luke’s voice, when it came, was simple. No speeches. No promises he couldn’t keep.

“Thank you for tellin’ me,” he said. “You didn’t have to. But you did.”

Willa blinked hard. No tears, just breath. And in that breath, something let go.

For the first time since she’d stepped onto that auction stage, she wasn’t a shadow.

She was Willa Mercer.

And she was done being erased.

A few days later, light moved across the floorboards in a slow gold spill. Dust hung in the air like quiet movement stirred by nothing. It was the kind of morning where stillness didn’t feel empty. It felt earned.

Willa woke expecting the usual: a tin cup, a rag by the basin, the world requiring nothing more than survival.

But on the table sat a small mirror, oval and silver-edged, aged at the corners but cleaned with care. Propped against a smooth wedge of pine, angled toward the light so the rising sun poured gently over it.

Beside it lay a scarf, faded silk the color of dust after rain. Folded neat. No note. No instructions. Just an offering that didn’t demand gratitude.

Willa stopped. She didn’t reach for it right away.

She had never needed glass to know her face. The scar was no stranger. It was a path she had memorized with her fingertips in darkness, measured in silence. But seeing is different than knowing. Seeing invites the world in, and the world had been unkind.

She sat and looked.

Not with dread. Not with defiance.

With the stillness that comes only after you’ve survived the worst and discovered you’re still here.

Her hand lifted. She traced the scar, not like something to erase, but like something lived through. The way a soldier might touch the edge of a medal they never asked for.

Then her eyes moved to the scarf. She picked it up. It slipped through her fingers like smoke in morning air, cool and soft and worn in places. There was weight in the fabric, not from age but from memory.

She tied it around her head, not to hide, but to choose what others would see. To soften the harshness. To say: This is mine now.

Behind her, the door creaked.

Luke stood in the doorway, hat in hand. His voice was quiet.

“That used to be my wife’s,” he said. “She wore it whenever she needed to feel like herself again.”

Willa’s fingers brushed the scarf near her temple.

Luke met her eyes, steady as fence wire. “Anyone who tries to make you ashamed of what you lived through is blind.”

He paused, then added, almost gently: “And the blind don’t get to judge beauty.”

Willa’s throat tightened. She didn’t cry. She breathed fully, like her lungs were remembering what air could feel like when it wasn’t borrowed.

Then she laid her palm flat against the mirror, not to test what she saw, but to meet it.

And in that morning light, in borrowed silk and her own name, Willa Mercer let herself be seen.

Spring soaked deeper into the soil. The stream ran louder. Birds returned and began to argue joyfully in the branches. Willa found a rhythm that didn’t feel like waiting for disaster.

She fetched water. Hung linens. Stitched a new dress one careful thread at a time. She learned the cabin’s sounds, what the wind meant when it pressed against the roof, when the boards complained, when the fire needed feeding. She didn’t wear the scarf every day, but she didn’t fold it away either. It stayed draped over the back of the chair, present as a promise.

Luke worked outside in the clearing, building something near the edge of the grass where trees began. Four upright beams. A crossbar. An arch rising like a doorway meant for a different kind of future. He didn’t say what it was. He didn’t have to. Willa could read hope in the angle of his hammer.

But peace has a short reach in places like this.

And it never holds without being tested.

One morning, a horse rode into Red Bluff carrying a man in a long duster torn at the shoulders, dust-colored from days of hard travel. His face was narrow, his eyes gray and flat. They moved like blades, assessing where to cut.

He introduced himself in the saloon as a traveler looking for work, but he didn’t smell like a drifter. He smelled like hunger.

His name, he said, was Ford.

Ford asked questions like he was tossing bones to dogs, seeing which one would chew.

“Any talk of a scarred woman come through?” he asked, smiling without kindness. “Heard she might be dangerous. Blood in her past.”

Rumor had made it up the trail ahead of him.

When he found Luke unloading grain near the supply shed, Ford tipped his hat.

“You Thatcher?” he asked.

Luke watched him the way you watch a rattler sunning on a rock. Calm, but ready.

“You live alone up there?” Ford pressed, eyes flicking toward the woods like he already knew the answer.

Luke didn’t give him the satisfaction of words. But his jaw moved. That was enough.

That evening, when Luke returned to the cabin, his face was quiet but colder than usual. Willa was by the stove, ladling stew into a tin bowl. She didn’t ask what was wrong, not yet. She’d learned that men who came home carrying trouble sometimes needed to set it down themselves before anyone else touched it.

Luke set his hat on the hook. He looked at her, eyes steady.

“He’s huntin’ you,” he said.

Willa didn’t ask who. She didn’t need to. Fear has its own handwriting.

She crossed the room without a word, opened the cedar chest, and pulled out the sack.

It was folded neatly, unworn for weeks. She held it in both hands like a relic of a past life.

“I’ll wear it again,” she said.

Luke stepped forward, voice firm but not commanding. “You don’t have to.”

Willa met his gaze. “I choose it,” she said. “Not to hide. To move unseen.”

That night, they laid a plan in the quiet of the hearth.

Willa would ride east before sunrise down the narrow logging trail. The sack pulled tight. Ford would follow, because a woman alone and hidden would be too tempting for a man like him to resist.

Luke would ride west over the ridge to the sheriff’s station. If they timed it right, the deputies would be waiting where the rocks narrowed into a passage carved by water and time.

It was a trap. Not born of cruelty. Born of necessity.

And if there was a grim poetry to using the sack that once silenced her as bait to catch the man who wanted to silence her again, Willa didn’t flinch from it.

Before first light, she mounted Luke’s bay gelding. The sack was tied firm. Her heart beat like a drum, but her hands were steady.

She didn’t tremble.

She didn’t look back.

She rode.

By late afternoon, Ford took the bait. He followed her into the eastern rocks where the trees narrowed and the world felt like a throat.

At the end of the passage, waiting behind stones with rifles drawn, stood Luke and the sheriff of Red Bluff and two ridge deputies.

Ford drew first, but not fast enough.

They brought him down hard, disarmed him, bound his hands behind his back. They slung him over his own horse like a sack of grain.

“Unlawful pursuit,” the sheriff muttered, spitting in the dust. “Intent to harm. Reckless threat of violence.”

Ford didn’t speak.

High on the hill, Willa watched it unfold, still wrapped in the sack, still silent. Only once Ford was gone did she ride down.

Luke stepped toward her, arms ready to help her dismount. Willa accepted the gesture, not because she needed it, but because she trusted it.

Then slowly she untied the knot and pulled the sack away. She folded it once, twice, held it like something that had served its last terrible duty.

“It saved me,” she said. “Not because it hid me. Because I used it.”

Luke nodded. “What’ll you do with it now?”

Willa looked toward the cabin. Toward the arch rising behind it. Toward the wide sky that didn’t care who had once tried to crush her.

“I’ll keep it,” she said. “Not as a burden. As a testament.”

Luke’s brow lifted slightly. “A testament to what?”

Willa’s mouth curved into a calm, almost reverent smile.

“That what once bound me has no power now,” she said. “That the yoke was broken, and I walked free by my own choosing.”

The days that followed were quieter, but quiet isn’t the same as safe. Justice in the Territory had a slow gait, and it liked to pretend it was tired.

Back at the cabin, Willa hung laundry with bare hands. No gloves. No veil. Her dress fluttered in the wind, simple and mended and hers. Luke worked at the table with a chisel, carving a final detail into the top beam of the arch he’d built. Linen lay folded nearby, edges weighted with river stones so the breeze wouldn’t steal it.

Late one morning, a rider appeared at the edge of the woods.

The sheriff. Dust clung to his coat. His horse sweated. In his hand, loose but certain, was a sealed envelope.

Luke met him near the clearing. No ceremony. No questions. The sheriff handed over the letter, tipped his hat, and rode away.

Luke stood still for a moment, the envelope heavy in his grip, then carried it inside like it might shatter if the air touched it too hard.

Willa was at the mirror, scarf draped over the chair behind her. Hair unbound. Hands still.

Luke held out the envelope without speaking.

Willa took it. Her fingers trembled once as she slid her thumb beneath the seal.

She unfolded the paper and read the words first silently, then aloud, voice steady and disbelieving all at once.

“Charges against Willa Mercer dropped. Case closed. Warrant rescinded.”

She stared at the letter as if it might change its mind. Then she folded it slow, careful as prayer.

“What changed?” she asked softly, like she was afraid to jinx the world by speaking too loud.

Luke’s expression tightened, then eased. “Someone finally spoke,” he said.

And though Willa didn’t know it yet, it was true.

A woman named Anna Turner, the one who’d once stood in a kitchen doorway and looked away, had written three pages of plainspoken truth. Signed with a steady hand. Mailed to the courthouse in Helena herself.

Sometimes justice doesn’t move until a woman shoves it forward.

Anna shoved.

Willa stepped outside, letter in hand. She walked past the woodpile, past the split-log bench, toward the clearing where the arch waited under open sky.

Luke was there, brushing sawdust from his palms.

Willa stopped beside the arch. The linen cloth, already hung, moved slightly in the breeze, catching threads of sunlight between shadow.

She didn’t cry. Didn’t smile right away either.

She just breathed.

For the first time since she was sold to silence, her breath came without weight.

Then she turned to Luke, eyes bright with a new kind of resolve.

“I want to use the sack,” she said.

Luke’s brow furrowed. “You sure?”

Willa nodded. “Not the way it was,” she said. “Not to hide.”

She held the letter tight. “I want to make something from it. Something I choose.”

Luke’s face softened, the way hard ground softens under steady rain. “Then we’ll make it,” he said.

Spring came fully after that, green without apology. Wildflowers pushed through rock like stubborn little triumphs. The wind stopped whispering warnings and started carrying warmth.

They didn’t send word across town. They didn’t call a crowd.

But the people who mattered came anyway, because good news travels differently than gossip. It doesn’t sprint. It settles in. It stays.

Anna Turner arrived up the ridge path wearing a cotton dress that didn’t match anything but her own spirit. She carried a small bouquet of yellow bells. The old blacksmith from Red Bluff brought a jug of applejack. The baker brought bread wrapped in worn calico.

They were not many.

They were enough.

Inside the cabin, Willa stood before the mirror. Her dress was cream muslin, hand-stitched, not fancy but flawless in its honesty. She’d sewn it over three nights, needle steady, breath slow.

On her head she wore a veil.

It had once been a sack.

She and Luke had washed it together, soaked it in sun, trimmed its edges with white thread meant to hold old fabric together without showing the stitches. In each corner she’d embroidered faint purple wildflowers, the same shape as the uneven flowers on the small cloth Luke carried in his coat.

It no longer resembled something meant to erase a person.

It looked like something claimed.

When Willa stepped outside, the forest paused. Not because the trees cared about human vows, but because the moment felt like it deserved a hush.

Luke waited beneath the arch. Hair combed back. Boots scrubbed clean. He wore his only shirt without sap stains. It hung stiff on his shoulders, but the way he stood in it made it fit. He looked at Willa, and everything else fell quiet: wind, leaves, the old ache of what came before.

Willa walked toward him without hesitation, not like someone being given away, but like someone choosing her own doorstep.

When she reached him, Luke took her hands.

“No matter what covered your face,” he said, voice rough but steady, “you were always the woman I chose.”

His eyes held hers like a promise hammered into place.

“And now you’re the woman I vow to stand beside to the end.”

Willa smiled, not with the caution of someone testing hope, but with the quiet peace of someone who had stopped running.

“I vow the same,” she said.

There was no preacher, no scripture, no grand speech. Just them, the trees, and the few people who stayed when it would have been easier to look away.

They kissed, soft and certain.

Above them the linen caught the wind like a sail. A few drops of rain fell, light as breath. No one moved to shelter. It felt like blessing, not weather.

Anna leaned toward the blacksmith and the baker and murmured, half laughing, “Never thought I’d see a burlap sack turned into a wedding veil.”

The blacksmith smiled, deep lines in his face easing. “Ain’t the sack,” he said. “It’s what she turned it into.”

That night, when the fire cracked low and the guests had gone, the woods held the cabin gently. Like a home earned rather than given.

Willa sat beside Luke on the porch. The veil lay folded in her lap, her fingers tracing the embroidered edges.

“This used to mean everything I feared,” she said quietly.

Luke looked at her, waiting, never pushing.

Willa’s smile came then, small but steady, like a lantern finally lit inside a long-dark room.

“Now it means everything I chose.”

Luke reached for her hand. Their fingers wove together, not like a cage, but like a braid made for strength.

They sat that way until the stars came out, sharp and bright in a sky that didn’t care about scars, only about light.

Their love didn’t erase the past. It didn’t heal every wound, and it didn’t pretend the Territory was kinder than it was.

But it did something rarer.

It turned what once hurt them into something that could bless them.

Because sometimes, in hard country where stories break, survival isn’t just about holding on.

It’s about choosing what to hold on to.

THE END

News

No Widow Survived One Week in His Bed… Until the Obese One Stayed & Said “I’m Not Afraid of You”

Candlelight trembled on the carved walnut door and made the brass handle gleam like a warning. In the narrow gap…

How This Pregnant Widow Turned a Broken Wagon Train Into a Perfect Winter Shelter

The wind did not blow across the prairie so much as it bit its way through it, teeth-first, as if…

“Give Me The FAT One!” Mountain Man SAID After Being Offered 10 Mail-Order Brides

They lined the women up like a row of candles in daylight, as if the town of Silverpine could snuff…

The Obese Daughter Sent as a Joke — But the Rancher Chose Her Forever

The wind on the high plains didn’t just blow. It judged. It came slicing over the Wyoming grassland with a…

He Saw Her Counting Pennies For A Loaf Of Bread, The Cowboy Filled Her Cupboards Without A Word

The general store always smelled like two worlds arguing politely. Sawdust and sugar. Leather tack and peppermint sticks. Kerosene and…

He Posted a Notice for a Ranch Cook — A Single Widow with Children Answered and Changed Everything..

The notice hung crooked on the frostbitten post outside the Mason Creek Trading Hall, like it had been nailed there…

End of content

No more pages to load