The courthouse porch sat above the street like a stage built for small cruelties.

Heat shimmered off the hard-packed dirt. Flies circled the sweat-dark collars of men who’d come to watch a bargain made out of a woman’s life. The building’s whitewashed boards were meant to look clean, but the wood at the steps was scuffed in the same places it always was, where boots had kicked and spurs had scraped and somebody’s dignity had been dragged over it again and again.

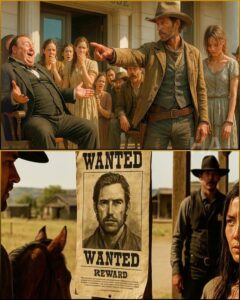

Judge Harlan Whitcomb leaned back in his chair as if the whole territory belonged to him, as if he’d personally hammered the horizon into place. His smile was the kind that never warmed his eyes.

“Pick any wife for free, boy,” he drawled, loud enough for the street to hear. “No one here will stop you.”

Laughter rolled through the crowd right on cue, like a wagon hitting the same rut it always hit.

A neat line of women stood along the steps, close enough together that their skirts brushed. Someone had bothered to brush their hair, patch their dresses, wipe the worst of the grime off their faces. They looked like tired portraits of fear painted over with a thin varnish of “presentable.”

At the far end of the line, though, there was one figure that didn’t belong in any marriage market.

Her ankles were bound with rust-bitten iron chains. The cuffs were too big for her, like they’d been built for a different body, a different person, and cinched down with spite. Her dress wasn’t really a dress at all, just gray cloth clinging to a thin frame. Her hair hung forward like a curtain, hiding most of her face, as if even the sight of her had been deemed unnecessary.

She stood pressed to a porch post as if she hoped the wood might open and swallow her whole.

No one in the crowd bothered to look her way.

No one except the cowboy.

He’d been standing at the edge of the street with his hat tipped low, the shadow hiding his eyes. He was tall in the way a man gets tall when he’s spent years walking under open sky, shoulders cut by work, posture held by stubbornness. His dust-colored duster had seen too many miles to brag about it. His boots didn’t shine. His revolver sat on his hip without swagger, like a tool that didn’t care about applause.

He watched the judge’s little game with a stillness that felt deliberate, almost dangerous, like a match held close to a fuse.

Then he stepped forward.

His boots sent lazy puffs of dust into the sunlight. People shifted to make space, not out of respect but because the kind of quiet he carried made them uneasy. He stopped square in front of Judge Whitcomb’s chair.

His voice was even.

It cut through the heat like a blade.

“Her.”

The laughter snapped off, sudden as a lantern snuffed.

Someone coughed. Someone muttered, “He’s gone mad,” like saying it out loud might make it true.

Judge Whitcomb’s eyebrows climbed in exaggerated surprise. “That one?” He leaned forward, elbows on his knees, studying the cowboy like a card player trying to read a bluff. “Boy, she’s not fit to keep a dog company, let alone a man.”

The cowboy didn’t blink.

“Her,” he said again.

This time, the chained girl’s head tilted just enough for him to catch a glimpse: a bruise blooming along her cheekbone, a thin line of blood crusted at her lip. And behind that, a pair of eyes—sharp, steady, watching him the way a cornered animal watches a hand reaching into its cage. Not begging. Testing.

Judge Whitcomb’s mouth twisted into something between amusement and satisfaction. He waved two deputies closer as if he were calling for drinks.

“Fine,” he said, too easily. “She’s yours to ruin. Unlock her and get this over with.”

The deputies stepped toward the girl. One fumbled for a key ring. The other gripped her arm too hard, because power enjoys practicing.

The cowboy moved before they could drag her anywhere.

His hand shot out, plucking the key from the deputy’s belt like he’d done it a thousand times. He dropped to one knee in front of the girl and went to work on the chain himself.

Metal clanged against wood when it fell, heavy and loud. Angry red grooves marked her skin where the iron had bitten in.

She didn’t thank him.

She didn’t even look at him.

She just shifted her bare feet on the splintered boards and waited, as if she’d learned long ago that kindness could be a trap in a different disguise.

The cowboy stood and held out his hand.

“Let’s go,” he said.

She stared at his hand like she was weighing whether taking it would save her or damn her. Then, slowly, she slid her fingers into his. Her grip was light but tight in a strange way—like a person holding onto the last rung above a drop.

They walked down the courthouse steps together.

The crowd parted with a restless murmur. A woman in a blue bonnet tugged her little boy back as they passed, like the girl carried something contagious.

Judge Whitcomb’s voice followed them, slick as oil and just as flammable.

“You’ll wish you’d picked different, boy. That girl isn’t just trouble. She’s got a mouth that’ll hang a man.”

The words lodged in the cowboy’s mind like a burr under a saddle.

He glanced down at the girl beside him, at the way she walked without leaning on him even though her ankles were raw, at the way she kept her chin level like pride was the only thing nobody had managed to steal yet.

He wondered exactly whose noose she might be holding in her silence.

The moment they stepped off the courthouse porch, the air changed.

It wasn’t the noon sun or the dust stirred by passing wagons. It was the way eyes followed them—slow, deliberate, the way a rifle barrel turns.

Whispers moved through the crowd like wind through dry grass.

“That’s her…”

“You know what she did?”

“He won’t last the week.”

The cowboy didn’t slow. His hand stayed clasped with hers, and he felt the tremor in her fingers. Not fear exactly. More like something held too tight inside, something that had nowhere safe to spill.

They reached his bay mare tied at the hitching post. He swung up first, then lifted the girl carefully into the saddle in front of him.

As his boot found the stirrup, a sharp voice cut through the low murmur.

“Mercer.”

He turned.

Sheriff Asa Kincaid leaned against a rail, arms crossed, badge catching the light like a warning. His hat sat back on his head the way lawmen wore theirs when they wanted you to see their face.

“You sure you know what you’re taking home?” the sheriff asked.

The cowboy’s jaw tightened. “I know enough.”

Sheriff Kincaid’s gaze slid to the girl. “Enough to hang you, maybe.”

The girl froze. Her fingers locked around the saddle horn.

The sheriff stepped closer, slow, boots crunching dirt. His mouth twisted into a smirk that didn’t quite make it to his eyes.

“Tell him,” he said, voice sharpened. “Tell him what you saw that day.”

The girl’s lips pressed together. A muscle flickered in her jaw. She said nothing.

Sheriff Kincaid leaned in, just a little, like a man who enjoyed watching a dog refuse a bone because it knew the bone was poisoned.

“She won’t,” he told the cowboy. “Because she knows you’ll throw her back the second you hear it.”

The cowboy shifted in the saddle, placing his body between sheriff and girl the way a wall decides to be a wall.

“You done?” he asked.

Sheriff Kincaid’s eyes narrowed. “You want to play hero, Wade Mercer, that’s your business. Just don’t bring her back into my town when it blows up in your face.”

The cowboy didn’t rise to the bait. He simply clicked his tongue, and the mare stepped out.

As they started down the main street, the girl spoke for the first time since he’d freed her. Her voice was low, almost swallowed by the clatter of hooves.

“You shouldn’t have chosen me.”

Wade glanced down at her profile. Bruised. Thin. Eyes fixed straight ahead, like looking to either side might invite memory.

“Too late for that,” he said.

She shook her head once. “Not too late for them to come after you.”

Wade didn’t ask who they were. He’d heard enough in her tone to know the answer would come only when she decided.

But the way she said it—like a promise carved into stone—told him whatever she carried wasn’t just dangerous.

It was still out there watching.

And somewhere behind them, on that courthouse porch, Judge Harlan Whitcomb leaned forward in his chair, tracking their departure with the satisfied look of a man who’d just lit a fuse and settled in to enjoy the burn.

Wade Mercer had not ridden into Cedar Run intending to buy a wife.

He’d come for supplies, to rest his horse, to ask after a missing herd line that had been cut east of the river. Simple needs. A simple town. The kind of town where men pretended their hands were clean because they washed them in public.

But he had watched the porch scene unfold and something old and sour had risen in him, the same feeling he’d carried since he was seventeen and had watched a man with a badge laugh while a boy took blame for a crime he didn’t commit.

Wade had left home that year, not because he wanted freedom, but because he wanted distance from the way power could grin and call itself lawful.

As the mare trotted past the last clapboard house, Wade kept his arm braced around the girl to steady her. She sat stiffly, refusing to lean back against him even though the saddle jostled her. Pride again. Or caution. Or both.

Half a mile beyond town, the road narrowed between two low ridges. Mesquite and scrub clung to the slopes. It was the kind of place where sound traveled strangely, where a man could be herded like cattle without noticing until the trap closed.

Wade’s eyes lifted to the treeline on his right.

A flicker of movement. A shadow where there shouldn’t be one.

The girl’s body went rigid against his arm. Her gaze cut sideways without turning her head, like she’d learned how to see danger without appearing to see it.

Wade slowed the mare. Her ears swiveled. Muscles bunched under the saddle.

A figure stepped out into the road ahead.

Big man. Dusty duster. Hat pulled low. Rifle hanging loose but angled enough to matter.

“You’re a hard one to catch, Mercer,” the man called, voice carrying the rasp of old whiskey and older grudges.

Behind them, hoofbeats thudded. Another rider, closing off retreat.

Wade didn’t turn, but he felt the shift in air, that tightening that made a man’s skin know it was being measured for a grave.

The girl’s fingers clamped down on the saddle horn so hard her knuckles went pale.

The man in the duster glanced at her and grinned without warmth.

“Judge sends his regards,” he said. “Says the lady belongs back where you found her.”

Wade’s reply was calm. Too calm, almost, like steel that didn’t need to shout.

“Tell the judge he can come say that to me himself.”

The second rider drew closer from behind. Leather creaked. Horse snorted.

“Ain’t how this works,” the man said. “She saw something she shouldn’t have, and the judge aims to keep it that way.”

The girl’s voice came sudden and sharp, surprising Wade and, for a heartbeat, surprising the men too.

“If you kill him here,” she snapped, “everyone will know why.”

Silence froze the air.

The man’s smile faltered, replaced by calculation. “Then we’ll make it look like an accident.”

Wade’s hand eased toward his revolver. His other arm tightened around the girl’s waist, protective without asking permission.

The rifle angled higher, putting Wade’s chest in a straight line of intent.

“You thinking of drawing on me, Mercer?” the man asked.

“No,” Wade said, eyes locked on the girl’s profile. “I’m thinking we’re not staying in this conversation much longer.”

He spurred the mare hard to the left, not toward open road but straight into scrub and low brush, where branches would snag and sightlines would break.

The rifle cracked.

A bullet whined past Wade’s ear, hot enough to feel like a warning whispered by fire.

The mare lunged into a gallop. Dirt and stones exploded under her hooves. Behind them, shouts rose. Pursuit thundered close enough to taste.

The girl twisted in the saddle to look back, hair whipping into Wade’s face.

“They won’t stop,” she said, voice half warning, half confession. “Not until I’m dead. Or until the judge is.”

Wade didn’t answer.

He didn’t need to.

Whatever she’d seen had turned his choice on that porch into a war line scratched in dust.

And wars on the frontier didn’t end with apologies.

They ended with someone not getting back up.

They didn’t stop until the mare’s flanks were lathered and the shouts behind them thinned into nothing but wind.

Wade guided them into a narrow gully hidden by spilled rocks and cottonwoods, a place he’d once used when he needed the world to forget where he was. A thin ribbon of water trickled over stones into a shallow pool.

Shade cooled the air. The smell of damp earth made the whole place feel like a secret.

Wade swung down first, boots landing in soft dirt. He lifted the girl carefully from the saddle.

Her bare feet touched the ground and she swayed, catching herself against the mare’s shoulder before stepping back, like she didn’t trust contact not to turn into control.

Wade led the mare to the pool. He watched the girl from the corner of his eye.

She stared at the stream as if she couldn’t decide whether to drink or drown.

“You want to tell me what that was back there?” Wade asked finally.

The girl shook her head once. “No.”

Wade repeated it, not loud, but with the quiet challenge of a man who’d walked through enough lies to know when one was being used as a shield.

“No,” he said. “That’s all you got?”

She crouched and cupped water in her hands. It ran over her wrists. She didn’t drink at first, just let the cold remind her she was still alive.

“You think picking me in front of him was charity?” she asked, voice rough. “It wasn’t. You put yourself in his sights now.”

Wade crouched too, lowering himself so he wasn’t towering over her. “I already had sights on me,” he said. “Comes with having a spine.”

Her mouth twitched, not quite a smile. “Once you’re there,” she said softly, “you don’t get out.”

Wade studied her. The bruises were fresh. The fear wasn’t loud, but it was deep, the kind that settles into bone.

“You saw something,” he said. Not a question.

Her eyes flicked up, sharp and assessing. “Something worth killing me over.”

Wade felt the words land in him like a rock dropped into a well. “Why hasn’t he already done it?”

A humorless half smile. “Because he needs people to believe he’s untouchable,” she said. “Shooting me in the street ruins the show. Selling me… chaining me… that’s quieter. That looks like justice in their eyes.”

She stood, brushing dirt from her skirt. For a moment, the set of her shoulders wasn’t prisoner. It was soldier.

“When he realizes he can spin it another way,” she added, “he’ll send someone who doesn’t miss twice.”

Wade rose too and scanned the ridge line above the gully. “Then we don’t give him the chance.”

She looked at him for a long beat, as if testing whether the words were real or just the kind men said when they wanted to feel heroic.

Then she spoke again, quieter.

“My name isn’t the one the sheriff used.”

Wade waited, letting silence coax the truth.

She inhaled like it scraped her ribs. “It’s Eliza,” she said. “Eliza Hart.”

No surname story. No explanation. Just the name, offered like a fragile coin she couldn’t afford to lose.

Wade nodded once. “Eliza.”

She flinched slightly at hearing it spoken gently.

“Night travel,” Wade decided. “We move when the sun’s down.”

Eliza’s eyes slid toward the mouth of the gully.

Wade followed her gaze and caught a distant glint of sunlight on metal high up the ridge.

A rifle barrel. Watching.

Eliza’s voice went flat with certainty. “They’ve already found us.”

Wade didn’t waste time arguing with truth. He grabbed the reins and pressed them into Eliza’s hands.

“Stay behind me,” he said. “No matter what.”

She didn’t argue. She simply stepped where he told her, like she’d learned how to survive by moving when there was no time to question.

A pebble skittered down the slope.

Then the metallic click of a lever being drawn.

Two men dropped into the gully from opposite sides, dust pluming around their boots. Both wore black kerchiefs at their necks, the kind Wade had seen on Whitcomb’s hired muscle.

One grinned. “Judge says the lady’s overdue for her rope.”

The other’s eyes never left Eliza.

Wade lifted his revolver, low but ready. “Funny,” he said, voice steady. “I don’t recall the judge owning the law outside his porch.”

The grin widened. “He owns everything worth owning in this county,” the man said. “Including the stories folks tell. You vanish out here, they’ll call it a brawl over a card game and forget your name by sundown.”

Eliza stepped out from behind Wade before he could stop her.

Her bare feet and torn dress should’ve made her look small.

But there was nothing fragile in her stare.

“If you take me back,” she said, voice clear, “you’ll be standing in the same room when he decides you’ve heard too much.”

The two men glanced at each other.

Wade saw it: they hadn’t known the full reason. They’d been sent like dogs, not told why they were biting.

Eliza’s eyes didn’t move. “I watched Judge Whitcomb shoot Deputy Marshal Jonah Weaver in the back,” she said. “I watched him smile after.”

Silence snapped tight.

The man with the grin stopped grinning. The other lowered his rifle a fraction, uncertainty flickering.

“That’s a big claim,” the second man muttered.

“It’s not a claim,” Eliza said. “It’s why he chained me. It’s why he tried to sell me until I vanished without a grave.”

Wade lifted his revolver a little higher. “You’ve got one chance,” he told them. “Walk away. Pretend you never saw us.”

The second man took a step back, muttering. The first tightened his grip.

“Orders are orders.”

Wade fired.

Not at the man.

At the dirt by his boots.

The shot slammed into earth inches from leather. The mare reared. Eliza grabbed the saddle horn, steadying herself.

Echoes bounced off the gully walls.

The men hesitated, then scrambled up the ridge with curses tossed over their shoulders like rocks.

Wade holstered his gun and turned to Eliza.

“That true?” he asked quietly.

Eliza met his eyes. For the first time, there was no test in her gaze. Just grim certainty.

“I watched him fall,” she said. “And I watched the judge make it mine.”

Wade felt something hard settle into his bones.

If Eliza was telling the truth, this wasn’t just about saving one girl from chains.

It was about cutting the hand that had been strangling the whole territory and calling it law.

They rode until dusk bled violet across the prairie.

Wade stayed off the main trails, steering toward a wagon road that would lead to a small settlement where a man could buy supplies, swap a horse, and disappear into the shuffle of strangers.

But when they crested a ridge and saw the settlement below, quiet as a held breath, Wade’s stomach tightened.

A fresh broadside fluttered on a post outside the livery.

Even from that distance, Wade recognized the bold black print.

WANTED.

And beneath it, a rough sketch of a man’s face.

His face.

Eliza stiffened in front of him. “He’s faster than I thought,” she murmured.

They rode into town anyway, because you can’t outrun hunger forever.

Eyes lifted in doorways. Conversations stopped on porches. Curtains twitched.

Wade dismounted and tore the poster down. Folded it once. Tucked it into his vest as if it were nothing.

“We won’t stay long,” he told Eliza.

They walked toward the mercantile.

Two men stepped out to block the boardwalk. Badges pinned to their vests, but Wade could smell the hired on them. Too clean. Too eager.

“Evenin’, Mercer,” the taller one said, smirk loud as a bell. “Judge Whitcomb’s been looking for you.”

“You can tell him I’m not looking for him,” Wade replied, trying to angle past.

The second man stepped closer. “See, that’s the trouble. He put a price on the girl too. Dead or alive.”

The words dropped into the space like a stone. The town noise felt farther away all at once.

Eliza’s fingers brushed the back of Wade’s arm. Not a plea. Not quite fear. More like a signal.

She was ready to move if he was.

Wade looked at the men and let his voice go flat. “Then you better hope you can collect before someone else does.”

The taller man’s smirk faltered just enough for Wade to push past him, pulling Eliza with him into the alley behind the mercantile.

Boots scraped wood behind them.

“Going somewhere?” someone called.

Wade didn’t answer. He shoved open a back gate and led Eliza into the open prairie beyond.

Gunfire cracked behind them.

A shot splintered the fence post beside Wade’s shoulder.

Eliza didn’t scream. She ran.

They mounted in a rush, the mare surging forward, hooves striking sparks off stones. They didn’t slow until the township was a smear on the horizon.

Over the pounding of hooves, Eliza shouted, “You see now? It’s not just his men anymore. It’s everyone with a gun and a taste for coin.”

Wade’s jaw tightened.

He could feel the net tightening. Whitcomb wasn’t just hunting them.

He was turning the territory into a game where every stranger could become an executioner for the right price.

That night, under cottonwoods, with no fire to give them away, Eliza spoke again.

“We can’t keep running,” she said, staring into the dark like she could see tomorrow waiting there. “He’ll keep sending men until there’s nothing left to send. We end it or we die with it chasing us.”

Wade watched her face in the starlight. The bruises looked darker at night. The resolve looked sharper.

“Ending it means going back,” he said.

Eliza nodded. “The ledgers,” she whispered. “He hides records. Land deeds. Taxes. Who he stole from. I heard him tell his clerk where he keeps them.”

Wade’s eyes narrowed. “Where?”

“In the courthouse,” she said. “False wall behind the judge’s bench.”

Wade let that settle.

The courthouse was Whitcomb’s temple. Walking into it was walking into his teeth.

“And if we get them?” Wade asked. “How do we keep them from disappearing into a fire he starts?”

Eliza finally looked at him. In her eyes, there was something like a plan and something like an old wound.

“We make sure they’re in someone’s hands before he can touch them,” she said. “Someone who will put the truth in front of everybody.”

“And who would that be?”

Eliza’s mouth curved into a thin, humorless smile. “You’ll see.”

Wade didn’t press. He could feel the tremor in her legs when she stood, exhaustion sinking into her bones after too many days running from death.

He handed her the last strip of dried venison.

For a while they ate in silence, the prairie listening.

Somewhere out in the dark, a coyote cried, thin and lonely.

Wade stared at the stars and thought about the porch.

About the way Whitcomb’s laughter had sounded like a lock clicking shut.

Tomorrow night, Wade decided, they would walk back into that courthouse.

Not as hunted animals.

As men and women carrying the match to the fuse.

They approached Cedar Run under night’s cover, keeping to back alleys where shadows pooled thick.

The courthouse loomed pale in lamplight, a ghost of authority.

Eliza led Wade to a drainage grate beneath the porch, exactly where she’d said it would be. Her certainty wasn’t luck. It was memory carved by fear.

The metal groaned softly as Wade pried it free. They crawled into the narrow crawl space. Dust and cobwebs clung to clothes and hair. The floorboards above them held voices like a lid holds boiling water.

Whitcomb was holding court late, the room full of armed men. Wade heard the judge’s voice, smug and sure.

“They’re close,” Whitcomb was saying. “When they show themselves, we take them alive if possible. Dead if necessary.”

Wade found the loose board Eliza had described. He levered it up, revealing a hollowed space in the wall.

His fingers closed around a leather-bound ledger.

Then another.

Then another.

Heavy with names. Dates. Theft spelled out in the judge’s own hand, not even ashamed enough to hide the ink.

Eliza’s eyes locked on Wade’s, fierce with urgency and something like vindication.

They slid the ledgers into a burlap sack.

Wade nodded toward the crawl space exit.

Eliza shook her head.

Instead, she pointed to a trap door at the back of the judge’s platform.

“We go up,” she mouthed.

Wade hesitated. Every instinct in him screamed to flee with the evidence and live to fight another day.

But Eliza’s face in that dim crawl space held a truth Wade couldn’t ignore:

If they ran again, Whitcomb would chase again, and this time he would not play polite.

Wade pushed the trap door open.

They rose behind the judge’s bench like the dead climbing out of a story that refused to stay buried.

The courtroom fell into stunned silence.

Dozens of faces turned.

Dozens of hands hovered near guns.

Judge Whitcomb’s mouth opened in shock, then twisted into rage so fast it looked like the mask had been yanked off.

Wade lifted the burlap sack so everyone could see the ledgers inside.

“You might want to sit down, Judge,” Wade drawled, voice carrying to every corner. “You look like a man who’s about to choke on his own lies.”

Whitcomb’s face blanched. “Shoot them,” he barked.

But Eliza stepped forward before the room could obey.

Her bruises were stark in lamplight. Her bare feet on polished wood looked like an insult to the whole notion of “civilized.”

“You’ll want to hear this first,” she said, voice steady enough to quiet even men with itchy trigger fingers.

Whitcomb sneered. “You’re nothing,” he snapped. “A gutter rat with a filthy mouth.”

Eliza didn’t flinch.

She opened the top ledger to a page thick with names and neat columns.

“Every man you robbed,” she said, turning it so the crowd could see. “Every widow you bled dry. Every rancher you ruined with taxes you invented. And the night you shot Deputy Marshal Jonah Weaver in the back.”

A ripple moved through the room. Guns wavered. Eyes shifted from Eliza to Whitcomb.

An older rancher near the front stood slowly, like a man hauling himself up out of disbelief. His face was hard, weathered by years and wrongs.

“That true, Judge?” he demanded.

Whitcomb’s mouth opened.

No words came out clean.

Wade tossed a second ledger toward a man in the crowd.

Sheriff Asa Kincaid.

The sheriff caught it, startled, then began flipping pages. His jaw tightened with each line, each signature, each recorded theft.

“It’s all here,” Sheriff Kincaid said, voice grim. He looked up at Whitcomb like he was seeing him for the first time without the shine of fear. “Every word.”

The spell broke.

Murmurs swelled into shouts. Men who’d come to hunt Wade and Eliza found their rifles swinging away from them and toward the bench instead.

Whitcomb reached for a drawer.

Wade knew what was in it.

He drew and fired one shot that shattered wood an inch from Whitcomb’s hand.

“You’re done,” Wade said flatly.

Sheriff Kincaid stepped forward, badge gleaming, but his face no longer smug. It looked haunted, like he’d just realized how long he’d been standing beside rot.

“By authority of this county,” the sheriff said, voice tighter than before, “I’m taking you into custody for murder and theft.”

Deputies moved in.

Whitcomb lunged, furious, spitting curses that sounded like spoiled milk, but hands grabbed him. The judge’s chair scraped back. Papers scattered. The man who’d played king on a porch suddenly looked like what he was: a thief in clean clothes.

As Whitcomb was dragged away, Eliza turned to the crowd.

Her voice shook now, just a little, but it didn’t break.

“I told you once he’d never stop until someone made him,” she said. “Now you know why I was in chains.”

Silence fell in a different way.

Not fear.

Something closer to shame.

Wade stepped beside her, not claiming her, not displaying her, simply standing like a human barrier in case anyone decided to remember old habits.

Sheriff Kincaid swallowed. His eyes met Eliza’s. Whatever he’d meant on that porch, whatever games he’d played to stay alive in Whitcomb’s shadow, he looked smaller now.

“Miss Hart,” he said quietly, the title clumsy on his tongue. “You’re… you’re free.”

Eliza stared at him for a long moment. Then she nodded once, like she was accepting a fact, not a gift.

Wade touched her elbow gently. “Let’s go,” he murmured.

They walked out together into the night air.

The courthouse behind them buzzed with the chaos of a toppled tyrant. The sound was almost unreal, like listening to a storm after years of drought.

Outside, the stars had come out bright and cold, watching as if they’d been waiting to see whether men would finally do something decent.

At the hitching post, Wade helped Eliza into the saddle. He swung up behind her.

“Where to now?” he asked.

Eliza looked toward the open road.

“Somewhere the law means more than one man’s greed,” she said.

Wade nodded. “And somewhere you get boots.”

A tiny sound escaped her that might have been a laugh if her ribs had remembered how.

As the mare carried them into the dark, Wade glanced back once.

The courthouse porch was empty.

The chair where Judge Whitcomb had once sneered at the world was just an abandoned piece of wood under moonlight.

A reminder that even the loudest voices can be silenced when the truth gets dragged into daylight and refuses to be buried again.

They didn’t ride far that night.

Not because they couldn’t, but because the kind of exhaustion that follows survival isn’t just in the muscles. It’s in the soul, heavy as wet wool.

They camped near a creek. Wade built a small fire, shielded by stones. Eliza sat close enough to feel heat but far enough to keep her own space. Wade didn’t push. He’d learned, long ago, that freedom includes room.

When Wade handed her a tin cup of coffee, Eliza took it with both hands like it was sacred.

“I thought you were buying me,” she said suddenly, staring into the black surface.

Wade blinked. “Buying you?”

“That’s what men do in towns like that,” she said, voice quiet. “They pick. They take. They own.”

Wade poked the fire with a stick, watching sparks leap and die. “I didn’t pick you to own you,” he said. “I picked you because they wanted you invisible. And I’m tired of invisible.”

Eliza’s throat bobbed as she swallowed. “Most men are kind for a day,” she said. “Then they want payment.”

Wade looked at her then, really looked. The bruises. The raw ankles. The eyes that had learned to measure danger and still insisted on holding a line.

“I won’t pretend I’m a saint,” he said. “But I won’t make you a debt either.”

Eliza’s gaze stayed on him, searching for hooks.

She found none.

The creek gurgled softly, indifferent and faithful, moving on as it always did.

After a while, Eliza spoke again.

“You know,” she said, “when he chained me, he told me no one would believe a girl like me.”

Wade’s jaw tightened. “He was wrong.”

Eliza’s fingers tightened around the cup. “He wasn’t wrong about everyone,” she said. “Just about you.”

Wade felt something loosen in his chest, like a knot he’d carried without naming.

“Tomorrow,” he said, “we’ll find a town with a real marshal. We’ll make sure those ledgers get copied. Whitcomb’s friends won’t stop just because he’s in irons.”

Eliza nodded. “They’ll come.”

“Then we’ll be ready,” Wade said.

She stared at the fire for a long time. Then she whispered, almost to herself, “I want a life that doesn’t belong to a porch.”

Wade’s voice came gentle. “Then we’ll build one that belongs to you.”

Weeks later, in a different town with a different courthouse and a judge whose hands didn’t smell like theft, Eliza Hart stood in a borrowed dress and testified.

Her voice shook at first. Then steadied.

She spoke of the records room. The argument. The gunshot. Deputy Marshal Jonah Weaver falling like a cut rope. Judge Whitcomb smiling like murder was just another signature.

The room listened.

Not because she was beautiful.

Not because she was gentle.

Because the ledgers had made it impossible to call her a liar without calling the judge’s own handwriting a lie too.

Whitcomb’s power collapsed the way rotten wood collapses: fast once the weight shifts.

There were more arrests. More names. More men who had hidden behind “just following orders.”

Some cried. Some raged. Some tried to bargain.

The law, slow as it was, finally turned its face toward truth.

And in the quiet spaces between trials and paperwork and the long work of untying corruption from a community’s throat, Eliza began to learn a strange new habit:

sleeping without chains.

Wade helped her find boots that fit. He tried to make a joke about it, too, as if humor could soften the sharp edges of what she’d endured.

Eliza didn’t laugh much at first.

But one day, when Wade tried to teach her how to saddle the mare and she told him he was tying the knot wrong, she actually smiled.

It was small.

It was real.

It looked like sunrise touching a landscape that had forgotten it could be warm.

“You could go anywhere now,” Wade said to her one evening as they sat on a porch that belonged to nobody’s courthouse.

Eliza stared out at the road a long time. The wind moved through the grass like a secret being passed gently from blade to blade.

“I know,” she said.

“And?” Wade asked, trying to sound casual, failing slightly.

Eliza turned to him. “I want to go somewhere I’m not chosen,” she said. “Somewhere I choose.”

Wade nodded slowly. “Fair.”

Eliza’s eyes softened. “But I don’t want to keep running from every shadow,” she added. “And I don’t want to forget what it felt like when you said ‘her’ like I was a person.”

Wade swallowed, gaze dropping to his hands. “You are a person,” he said. “You always were.”

Eliza tilted her head. “Then maybe,” she said, voice cautious but brave, “we start with a place. Not ownership. Not debt. Just… a start.”

Wade looked at her, and for the first time, he let himself hope without turning it into a trap.

“A start,” he echoed.

Eliza held out her hand, palm up, not because she needed saving but because she was offering partnership.

Wade took it.

Not as a purchase.

As a promise.

And somewhere far behind them, in the dust of Cedar Run, a porch chair sat empty under sun, while a territory that had once laughed at chains began, slowly, to learn how to stop.

THE END

News

“At 19, She Was Forced to Marry an Apache — But His Wedding Gift Silenced the Whole Town”

The summer did not arrive in Kansas so much as it descended, slow and brutal, like a hand pressing the…

Buried to Her Neck for Infertility—Until Apache Widower with Four Kids Dug Her Out and Took Her Home

The wind didn’t weep for women like Sadi Thorne. It only passed over her skin as if she were a…

They Sent the ‘Ugly Daughter’ as a Mail Order Bride Joke — The Mountain Man Found His Perfect Mat

Horace Whitaker did not simply marry off his daughter. He disposed of her the way a man flicks ash from…

No Woman Lasted a Day With the Mountain Man’s Five Boys — Until a Little Girl Arrived… 💔🤍

The Montana mountains didn’t welcome visitors. They tolerated them the way a frozen river tolerated a boot: with patience right…

An Obese Noblewoman Was Handed Over to an Apache as Punishment by Her Father, But He Loved Her Like

The Arizona sun had a way of making the world confess. It confessed the truth of dust, for one, turning…

She packed her bags in silence, but the cowboy blocked the door and said something that made her…

The autumn wind worried the shutters of Henderson Boarding House like it had a grudge to settle. It shoved itself…

End of content

No more pages to load