March 3rd, 1838, Charleston, South Carolina, arrived with a cold rain that turned the cobblestones into dark mirrors. Elias Hart stepped around puddles and broken oyster shells, his boots making small, reluctant sounds, as if even leather wanted to argue with the direction he was going. The auction house on Meeting Street wore its respectability like a borrowed coat: white columns, polished brass handles, a door wide enough to swallow a carriage. Inside, the air smelled of damp wool, pipe smoke, and the sour sweetness of fear that no one named aloud. Elias had taught Latin and arithmetic to merchants’ sons for seven years and had learned a particular kind of silence, the kind that kept your rent paid and your ribs unbroken. He told himself he was only here to observe, because observation felt safer than action, and safety had become his private religion.

He had come because of a boy in his classroom, Henry Kincaid, twelve years old, neat as a ledger, cruel as a joke told twice. Henry had chatted about his father’s “sale” the way boys discussed a horse race, saying the household was being trimmed down now that his mother was gone. “There’s a woman they’re selling,” Henry had added, bright-eyed with the satisfaction of sharing an interesting fact, “and she reads better than I do.” Elias had pretended his chalk squeak was the reason his hand paused on the blackboard, but the truth was uglier. Literacy for enslaved people was illegal, or at least treated like a crime by men who called themselves God-fearing, and illegal things always meant secrets. Secrets always meant someone with power believed he could keep them.

The main hall held perhaps seventy men, though it could have held twice that, and the empty space made the crowd feel like a ring around a pit. There were planters with red faces, speculators with sharp smiles, a few ladies peering from a balcony as if suffering were theater, and several men who didn’t belong to any polite category at all. Elias noticed those men first, because violence has a posture, and these men carried it the way others carried umbrellas. The auctioneer, a hawk-nosed man named Silas Rourke, warmed up his voice by praising the “quality” of human bodies in the same tone a butcher used for cuts of beef. Each time his gavel tapped the podium, Elias felt something inside him flinch as if the sound were meant for bone instead of wood.

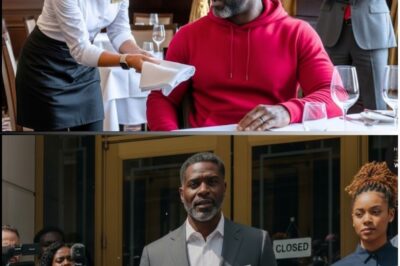

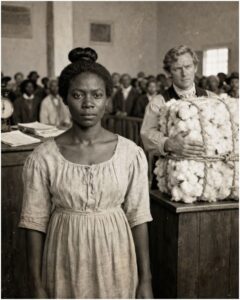

When the woman was brought out, the room shifted. She was about twenty-five, perhaps a little older, slim from hard years rather than delicacy, and dressed in a plain dress that was clean but tired, like a flag left too long in the rain. Her hair was pulled back tight, not for beauty but for control, and her hands were folded as if she were holding herself together by force. What struck Elias most was her gaze, level and direct, not the eyes of someone asking for mercy but the eyes of someone calculating exits. She looked over the crowd slowly, and when her attention passed over Elias, he felt a jolt that had nothing to do with recognition of a face and everything to do with recognition of meaning. It was the look of a person who knew the room was a trap and was measuring who might be foolish enough to spring it.

Silas Rourke announced, “A fine house servant, sound, steady, and yes, gentlemen, she reads. A rare convenience for correspondence.” He said it quickly, like a man slipping a ring into his pocket, and then he added the strangest part, the detail that made whispers scatter through the hall like startled birds. “Minimum bid, one bale of cotton.” Elias heard someone chuckle in disbelief, and someone else mutter, “That can’t be right.” In Charleston, an enslaved woman with household skills could fetch hundreds, sometimes more, and even men who pretended morality was optional understood numbers. One bale of cotton was not a price, not really, but a signal.

The crowd fell into an uneasy stillness. Men avoided the auctioneer’s eyes, studied their own boots, discovered sudden fascination with the ceiling beams. In a market built on cruelty, cheapness was suspicious, because it suggested damage, illness, or danger that had not been declared. Elias’s stomach tightened as he scanned the room, and his gaze landed on Colonel Ambrose Kincaid near the back, Henry’s father, a man with a tidy beard and the blank expression of someone accustomed to decisions that harmed others. Kincaid watched the platform like a chess player watching a pawn he intended to sacrifice, and when he noticed Elias looking, his eyes narrowed the smallest fraction, not anger exactly but annoyance that a stranger had wandered too close to his board.

“One bale,” Silas Rourke called, voice full of practiced cheer. “Do I have a bidder?”

No one moved. The silence felt heavy enough to be handled, like wet cloth, and Elias heard his own breath the way he heard his students’ pencils scratching during examinations. He told himself, firmly, that he would not raise his hand. He had no money to spare, no house, no right to pretend he could unmake a system with a gesture. But his hand rose anyway, almost disobediently, and his voice followed, hoarse and steadier than he deserved. “One bale.”

Every head turned as if yanked by the same string. Elias Hart, the quiet schoolmaster, the man who argued about Cicero but never argued about politics, had just bought his way into the room’s worst curiosity. Silas Rourke blinked once and recovered. “One bale from the gentleman in the rear. Do I hear another?” The hall stayed silent, and Elias watched Colonel Kincaid’s jaw tighten as if someone had pressed a thumb into an old bruise. “One bale, once,” Rourke said. “One bale, twice.” He hesitated, glancing toward Kincaid, offering him an invisible rope to pull the sale back from the edge. Kincaid gave a faint, sharp shake of the head. “Sold,” Rourke declared, and the gavel’s crack sounded like a door locking.

Paperwork swallowed Elias in minutes. He wrote his name with a hand that trembled despite the chill, and he heard himself give the address of his rented room above a bookbinder’s shop, as if he were describing a place that belonged to someone else. He handed over the bale of cotton he had bought days earlier for reasons he had pretended were practical, though his conscience had been planning behind his back. When the documents were stamped and the clerk nodded, the woman stepped down from the platform and approached him with controlled steps. Up close, Elias could see a thin scar near her temple and the fine lines of exhaustion around her eyes, the map of years that were not hers to choose.

She spoke so quietly that only he could hear. “You just made a terrible mistake, sir.” Elias swallowed, tasting bitterness. “I know,” he whispered, because humility was the only currency he had left. Her lips barely moved as she corrected him. “No. You don’t know. They will come for me tonight, maybe sooner. If you resist, they kill you. If you comply, they kill you. Your only chance is to learn what I know before they decide the easiest solution is to bury both of us.” Elias stared, his mind scrambling for a normal explanation to cling to, but nothing in her face offered normal. “Who are ‘they’?” he asked. She looked toward the door, where two men stood too still near the wall, pretending to admire a painting. “Men who don’t buy,” she said. “Men who take.”

He didn’t argue then, because fear has a way of sanding the edges off pride. He led her out the side entrance into rain that seemed suddenly too bright, too ordinary for what had just begun. Charleston’s streets were busy, wagons splashing through puddles, shopkeepers sweeping water away as if water were the day’s only problem. Elias walked quickly, not quite running, and the woman matched his pace despite shoes that pinched and a dress that clung damply to her knees. They drew stares, because a white man moving urgently beside a Black woman who did not bow her head disrupted the city’s choreography. Yet no one stopped them, not out of kindness but out of habit, because people rarely interfere with what they assume is law in motion.

His room above the shop was small: a narrow bed, a desk, shelves of books, a single window that looked out onto the street. Elias locked the door and dragged his desk against it, the gesture feeling childish and necessary at once. The woman went straight to the window and peered down with the focus of a person reading a page written in footsteps. “Two men across the street,” she said. “Same ones from the hall. They will wait until dark or until they grow bored. Bored men become violent.” Elias moved beside her and saw them: one with a scar by his mouth, the other broader, both pretending to be idle, both watching the shop door the way cats watch a mouse hole.

He turned from the window, because staring did nothing but tighten his throat. “What did you do?” he asked, and hated how accusing it sounded, as if survival were a crime. She looked at him as if weighing whether he deserved the truth. “I didn’t do anything,” she said. “I remembered.” Elias frowned. “Remembered what?” Her voice stayed even, but something underneath it sharpened. “My name,” she said. “And the names of the men who stole it.”

She drew a breath that seemed to carry years. “They call me Lettie,” she began, “because they think giving you a new name is the same as owning your breath. My name is Sarah Whitaker. I was born free in Philadelphia.” Elias’s mouth went dry. A free woman. Not “born free” as a metaphor, but in the legal, documented way that made Southern law squint and snarl. Sarah continued, watching his face the way a teacher watches a student’s understanding. She told him about a trip south to Baltimore to care for an ailing aunt, about the night three men dragged her from a bed and gagged her, about papers torn and burned while one of the kidnappers said, almost gently, “You were free. Past tense.” She described the wagon, the stench of straw and sweat, the two-day ride that ended in Virginia’s shadow and then Carolina’s. “They sell us where no one asks questions,” she said. “And if we claim freedom, they call us runaways and punish us for speaking.”

Elias felt rage rise like a fever, but rage did not give him a plan. “Colonel Kincaid,” he said slowly, because the boy’s name had been an arrow pointing somewhere. Sarah nodded once. “He bought me six years ago,” she said. “His wife liked having someone who could read her letters when her eyes weakened. She thought she was doing me a kindness, teaching me. I let her think it. Sometimes pretending is the only armor you’re permitted.” She leaned against the wall, placing herself where she could see both the door and the window, and Elias understood that she had been living like this for years, always braced for impact. “When his wife died, he stopped needing the illusion of kindness,” Sarah went on. “Then I saw something I wasn’t meant to see.”

She told him about a letter delivered by private courier, marked urgent, which the colonel’s trembling wife had asked her to open. It spoke of “shipments” and “items,” of “papers in order,” of profit margins as if human beings were barrels of molasses. Sarah had done what desperate people do when they are tired of dying in slow motion. She picked a lock, searched a desk, and found ledgers: names, dates, descriptions, purchase locations in Northern cities, and resales in Southern markets. “They kidnap free Black people and sell them,” she said simply, each word falling like a stone. “Not just Kincaid. There are others. A judge who stamps forged documents, a sheriff who looks away, and men who make bodies disappear when questions grow loud.”

Elias sat hard on his chair, because his legs forgot they were supposed to hold him. The world he had avoided naming now had names, and naming made it real. “Why sell you for one bale?” he asked, because the detail gnawed at him like a rat behind a wall. Sarah’s expression turned colder. “Because it wasn’t a sale,” she said. “It was a transfer. A clean one, public, legal. He meant for a specific buyer to take me, kill me, and then claim I ran. The low price was a signal to the buyer. A promise that this purchase came with instructions.” She looked toward the window again, where the men waited like punctuation marks at the end of a sentence. “You weren’t part of his plan,” she said. “Now you are.”

For a moment, Elias wanted to do what he had always done when confronted with danger: withdraw into thought, into books, into theories about morality that required no blood. But Sarah’s presence made that old habit feel obscene, like discussing etiquette while the house burned. “We must go to the authorities,” he said, because it sounded like the right line from the right play. Sarah’s laugh was quiet and humorless. “Which authorities?” she asked. “The sheriff who profits? The judge who signs lies? The city councilman who dines with Kincaid? In this city, law is a coat worn by whoever can afford it.” Elias’s mind flashed to one name, fragile and hopeful. “Reverend Nathaniel Cole,” he said. “He preaches on East Bay Street. He has spoken against slavery, carefully, but he has friends in the North. If we bring him proof, he might help.”

“Proof,” Sarah repeated, as if tasting the word. “Not stories. Not suspicions. Proof.” She moved closer, lowering her voice though no one could hear through walls thick with old brick. “Then we take it,” she said. “We go to Kincaid’s house and steal what he keeps locked away.” Elias stared at her, feeling the absurdity of it, the way a man feels when the ground asks him to become sky. “Break in?” he whispered. “While he’s home?” Sarah’s eyes sharpened. “Not break in,” she said. “Walk in. The servants know me. They will think I’m fetching belongings after a sale. No one questions that. They don’t question because questioning would mean admitting the truth, and the truth makes people responsible.”

Their plan was ugly in its simplicity. Elias would leave openly, draw the watchers away, play the part of a frightened man attempting to flee the city by ship. Sarah would return to Kincaid’s mansion, slip through the back like a shadow returning to its corner, and take the ledgers and letters that proved the conspiracy. They would meet at Reverend Cole’s church by dusk. Elias wanted to argue, to insist he should protect her, but Sarah gave him a look that cut through his instinct to be heroic. “You protect me by being alive,” she said. “If you die, the law calls it a robbery. If I die, they call it property lost. If we live, they have a problem they can’t bury.”

So Elias descended the stairs, stepping into rain that had eased into a gray drizzle, and forced his feet to move at a steady pace. The two men detached from their post across the street like dark thoughts separating from a mind and followed him without hurry. Elias walked toward the docks, asked a clerk about passage north, counted his coins with shaking fingers, and tried to look desperate rather than strategic. Each minute he kept them watching him was a minute Sarah had to become invisible inside Kincaid’s house. Yet time felt like a rope fraying in his hands, because he could sense the moment coming when the men would stop observing and start acting.

They confronted him in an alley near warehouses that smelled of salt and spoiled fish. The scarred one stepped forward, voice soft and sharp. “Where’s the woman?” Elias forced panic into his tone because it wasn’t difficult to find. “I let her go,” he said. The second man, broader, shifted to block the alley’s mouth, and Elias understood the geometry of murder. “You let eight dollars walk away,” the scarred man said, smiling without warmth. “That’s either mercy or stupidity. Which are you, schoolmaster?” Elias’s heart hammered, and he reached for a lie sturdy enough to hold their attention. “I didn’t want trouble,” he said. “I told her to run. I don’t know where she went.”

The scarred man’s eyes narrowed, not convinced, but interested. Interest was useful; it delayed violence. “Trouble found you anyway,” he murmured. “You ask questions, you make bids you can’t afford, and now you’re standing in an alley trying to act innocent.” Elias swallowed and gambled, because the truth sometimes buys time. “Colonel Kincaid sent you,” he said, and watched their faces, hunting for flinches. The broader man’s hand slid under his coat, metal gleaming briefly. “That’s enough,” the scarred man said. “Last chance. Where is she?”

Elias ran, because terror finally outweighed dignity. He sprinted deeper into the alley, shoes slipping on wet stone, lungs burning as if he’d swallowed fire. Boots thundered behind him, closing fast, and the world narrowed to corners and breaths and the sound of his own pulse. He burst onto a busier street and nearly collided with a woman carrying parcels. Shouts rose. Hands grabbed his coat. He fell hard, pain lancing his knee, and as he struggled upright he saw a city constable approach, club at his belt, uncertainty on his young face.

The scarred man’s voice became syrup. “No trouble, officer. He’s had a bit too much. We’re helping him home.” The constable looked at Elias. “That true?” Elias’s mouth opened, then shut. Sarah’s warning echoed: the sheriff is part of it, and a corrupt roof leaks everywhere. Elias forced a slur. “Bad day,” he mumbled. The constable’s expression curdled into disdain. “Get him off the street,” he said, and walked away, leaving Elias in the hands of the men who would not take him home.

They dragged him toward another alley, darker, quieter, and Elias felt the certainty of an ending press against his ribs. Then a voice cut through the rain. “Mr. Hart!” The words rang with authority, and the men paused like dogs hearing a whistle. Reverend Nathaniel Cole strode toward them, white collar bright against his black coat, a thin old man with eyes that missed nothing. “Elias Hart,” the reverend said again, louder, “we must speak about the Sunday school curriculum at once. It cannot wait.” He took Elias’s arm with a grip that felt like iron hidden in cloth and looked the men over. “Are these your companions?” he asked, tone polite enough to be dangerous.

Elias swallowed and seized the lifeline. “No, Reverend,” he said. “I’ve never seen them.” The scarred man offered apologies, claims of confusion, but Reverend Cole’s gaze held them like nails. “Confusion,” the reverend repeated softly. “How fortunate God sent me into the street at this moment.” He guided Elias away, step by step, and only when they turned a corner did Elias breathe again. “Tell me,” the reverend said without slowing, “why men shaped like violence were about to fold you into an alley.” Elias’s voice shook as he spoke, because the story was too large to carry neatly. He told him about the auction, the one bale, Sarah Whitaker, the kidnapping ledgers, and Colonel Kincaid’s plan to erase the evidence by erasing her.

At the church, the reverend locked the door and listened with a face that grew heavier with every detail. “I’ve heard whispers,” he admitted, “free folk vanished on roads south, families in Philadelphia hunting ghosts. But whispers don’t convict.” As if summoned by the weight of his words, a knock came, quick and urgent. A woman’s voice called, strained with breath and distance. “Reverend Cole. It’s Sarah. I have what we need, but they’re behind me.” Elias rushed to the door, heart tripping over itself, and the reverend hesitated only long enough to ask, “How do we know?” Sarah’s answer came crisp through the wood. “If they wanted in, they wouldn’t knock. They’d break it.”

When the door opened, Sarah stumbled inside, dress torn at the shoulder, a thin line of blood on her forearm. She clutched a leather portfolio like it was a beating heart she couldn’t afford to drop. “I got them,” she said, voice tight with triumph and terror. “Ledgers. Letters. Names. The judge. The sheriff. The trader who brings them south. All of it.” Reverend Cole drew the curtains and peered through a slit. “They’re here,” he murmured. “And they’re not ashamed.” Outside, men spread around the building like spilled ink, and a voice shouted, “Open in the name of the law.” Sarah’s face went pale. “Sheriff Mallory,” she whispered. “He’s part of it.”

The reverend moved with calm that felt like prayer made practical. “There’s a cellar,” he said, guiding them toward the altar. “A tunnel to the cemetery. Built during the Revolution. Follow it to the Preston mausoleum and go to the freight yard. Find Samuel Rusk and tell him I sent you.” Elias started to protest, but the reverend shook his head. “I will distract them,” he said. “They will not dare harm me openly, not yet.” Sarah looked at him with something like grief. “They’ll harm you later,” she said. The reverend’s smile was small and tired. “Later is a luxury you need,” he replied. “Go.”

They descended stone steps into earth-cold darkness, Elias carrying a lantern while Sarah held the portfolio tight against her chest. Above them, voices rose and fell as the reverend welcomed the sheriff with maddening politeness, offering cooperation while buying time with dignity. The tunnel pressed close, forcing Elias to hunch, and his injured knee throbbed with every step, but pain was simply another sound in a world full of alarms. “Do you think he’ll survive?” Elias whispered. Sarah’s answer was honest enough to bruise. “I think he’ll be punished for helping us,” she said. “This country punishes that.”

They emerged in the cemetery behind a mausoleum and moved low among headstones, using the dead as cover while the living hunted them. The freight yard was a chaos of wagons and shouting men, and chaos, for once, served them. Samuel Rusk was a thick-armed man with a face carved by labor and suspicion. When Elias said the reverend’s name, Rusk’s eyes narrowed, then softened into resignation. “The Reverend sends trouble,” he muttered. “Fine. Get in the back. No noise. I don’t want the story. I just want the road.” They hid among crates under canvas and rolled out of Charleston as night fell, the city’s lights receding like embers swallowed by dark.

In a boarding room outside Savannah, Sarah spread the documents on a narrow bed, and Elias read until his stomach felt scraped raw. The conspiracy was a machine with oiled parts: names of free Black men and women taken from Philadelphia, New York, Boston; notes about forged papers; payments split between Colonel Kincaid, Judge Horace Lyle, Sheriff Mallory, and a trader named Amos Drayton. There were mentions of “losses” that made Elias’s hands shake, because loss meant death described as a bookkeeping inconvenience. Sarah watched him with a strange steadiness. “This is what they meant to keep,” she said. “Not just me. The proof that they do this over and over, and sleep afterward.”

From Savannah they traveled to Washington, then north into Pennsylvania, because the farther they went the more air seemed to return to Sarah’s lungs. In Philadelphia, abolitionists and lawyers received the portfolio like a bomb handed carefully from one set of trembling fingers to another. A lawyer named Charles Whitcomb studied the ledgers and went quiet, his face tightening in anger that looked like discipline. “If these can be authenticated,” he said, “this will not simply ruin men. It will expose a method.” Elias heard the word method and understood why Kincaid had been willing to sell Sarah for almost nothing. A secret method is worth more than any single life, to men who trade in lives.

The months that followed were both swift and slow: swift in arrests, slow in justice. Federal marshals moved, not because morality suddenly arrived, but because documents create a kind of gravity even politicians fear. Colonel Kincaid was taken in Charleston, Judge Lyle dragged from his bench, Sheriff Mallory from his office, Amos Drayton from a warehouse stacked with cotton and lies. Newspapers argued as if outrage were a sport, Northern papers calling it proof of slavery’s rot, Southern papers calling it a smear against “respectable property holders.” Elias and Sarah waited in safe houses, hearing rumors like distant thunder, while lawyers built cases carefully enough to survive appeal. Waiting felt like helplessness, yet it was also strategy, a bitter lesson Elias had never learned in classrooms.

When the trial finally opened, Sarah walked into the courtroom upright, dressed in borrowed finery that did not hide the scars of her years. Elias sat behind her, feeling smaller than he had ever felt, not because the room intimidated him but because he understood how much she had carried alone. Defense attorneys tried to paint her as a liar, a runaway, a woman hungry for attention, and the accusations slid off her like rain off stone. She answered questions with precision, describing rooms, locks, letters, dates, the exact phrasing of Drayton’s correspondence, and then she produced documents from Philadelphia proving who she had been before Baltimore, before the wagon, before the fire that ate her papers. “You stole my freedom,” she said, looking directly at Kincaid, “and you thought you stole my name with it. But names don’t burn as easily as paper.”

Elias testified too, telling the plain story of a single raised hand in an auction hall, the threats that followed, the escape through a church tunnel that smelled of earth and history. The defense tried to call him an agitator, but he had never been an agitator. He was a man who had mistaken silence for innocence until silence began to taste like blood. The jury, all white men as the law demanded, deliberated long enough for Elias to fear that proof would not matter after all. When they returned, the foreman’s voice trembled, as if even he could feel the floor shift under the country’s feet. “Guilty,” he read, one name after another, and the word fell like a hammer striking more than wood.

Victory came with a shadow, because news arrived that Reverend Nathaniel Cole had been found dead in his church weeks after their escape. The official report called it “heart failure,” and everyone who mattered knew it was revenge. Elias stood in a Philadelphia street holding that news like a stone and realized that courage is never clean. Sarah didn’t cry in public, but later, in a quiet room, she pressed her palm to her mouth and whispered, “He bought us minutes. He paid with years.” Elias wanted to say something that would soften the truth, but nothing honest softened it, so he only said, “I won’t let them erase him,” and Sarah nodded as if that promise mattered because it was all they had.

In the years that followed, Sarah became what the kidnappers had feared most: a living ledger that spoke. She worked with abolition societies, helped other stolen people reclaim their identities, and traveled with careful protection because threats do not vanish when verdicts are read. Elias lost his job in Charleston without ever returning to resign; his landlord sold his books to settle unpaid rent, and his old students likely learned to forget his name. He found work in Boston teaching children who were denied education in most places, and he learned that teaching could be an act of repair as much as an act of instruction. He and Sarah wrote letters that were part friendship, part strategy, part confession, because both understood that survival is a task you perform daily, not a prize you earn once.

One evening years later, Sarah stood at a lecture podium in Philadelphia, older now, hair threaded with gray, voice still steady. She held up a copy of the auction receipt, the one that listed her as property sold for a bale of cotton, and she let the audience see how ordinary the paper looked. “Evil loves paperwork,” she said, and the room went still enough to hear lungs working. “It hides behind stamps and signatures. It calls itself lawful so it can sleep at night. But the same paper that tried to make me a thing became the paper that helped expose the men who stole me. That is the strange alchemy of truth: it can turn the tools of harm into the tools of witness.”

Afterward, Elias met her outside under gaslight that made halos of mist. “Do you ever wish,” he began, then stopped, because the question felt selfish. Sarah finished it for him, because she understood him too well. “Do I wish you hadn’t raised your hand?” she asked. Elias managed a small, pained laugh. “Yes,” he admitted. “Because it ruined your day. Because it ruined my life. Because it killed a good man.” Sarah looked up at the dark sky, as if searching for a star stubborn enough to pierce city smoke. “And because it saved others,” she said quietly. “Because it proved the machine can be jammed. Because it reminded a frightened teacher that silence is also a choice.” She turned to him, and her expression softened into something like mercy. “I don’t celebrate suffering,” she said. “But I won’t pretend the choice didn’t matter.”

Elias walked her to her door, and when they parted, he felt the old life he’d lost like a phantom limb. Yet he also felt something new, a kind of harsh clarity, as if his conscience had finally learned to speak in full sentences instead of whispers. History, he realized, is not only built by generals and lawmakers and men with statues waiting in their future. Sometimes it shifts because an ordinary person does a single unreasonable thing at the wrong time, and that wrong time becomes the first right moment. In an auction hall that pretended to be respectable, a schoolteacher bought a woman for the price of cotton, and discovered she carried not only a name but a map of crimes powerful men thought would stay buried. They tried to kill the map, the witness, the helper, and the pastor who offered them minutes, but the truth proved harder to strangle than flesh.

Years later, when Sarah’s memoir circulated in the North and was smuggled into the South despite bans and threats, some people read it and felt only anger, while others read it and felt something crack open that could not be closed. Elias kept one line from her book copied on a scrap of paper tucked inside his worn Bible, not because he was especially pious but because he needed reminders the way people need bread. The line was simple, almost plain: They stole my papers, but they did not steal my knowing. Whenever Elias felt himself sliding toward despair, toward the temptation to believe that systems always win, he read that sentence and remembered a woman in a gray dress on a platform, eyes lifted, refusing to look down even when the room demanded it.

And somewhere, in a country still arguing with its own reflection, the echo of that refusal lingered, stubborn as a heartbeat, insisting that a name is not property, a life is not inventory, and the smallest act of conscience can make the mighty tremble, not because conscience is powerful like a weapon, but because it is contagious like fire.

THE END

News

Billionaire’s Mistress Kicked His Pregnant Wife — Until Her Three Brothers Stepped Out of a $50M Jet

At 4:47 p.m., under the honest glare of fluorescent hospital lights, Briana Underwood Montgomery was exactly where she made sense….

Unaware His Pregnant Wife Was The Trillionaire CEO Who Own The Company Signing His $10.5B Deal, He..

The baby shower decorations still hung from the ceiling when the world cracked. Pink and blue balloons swayed gently in…

Unaware His Pregnant Wife Owns The Company, Husband And His Mistress Denied Her Entry To The Gala

Elena paused at the entrance of the Fitzgerald Plaza Grand Ballroom the way someone pauses at the edge of a…

My Husband Called Me ‘The Fat Loser He Settled For’ As His Mistress Laughed, But When I Showed Up At

The kitchen smelled like rosemary, onions, and the slow, sweet promise of a pot roast that had always been Derek…

End of content

No more pages to load