The snow attacked sideways, tiny hard pellets that stung like sand. His eyelashes began to clump; his eyebrows stiffened. He felt the cold trying to slip into him through seams in his coat, through the gap where scarf met collar, through the vulnerable place where pride met fear.

He held to the cliff line he couldn’t see, angling into the wind until his shoulders ached, counting steps, counting breaths, counting the seconds until his fingers went numb enough to betray him. He pictured the entrance the way he had measured it a hundred times: the dark gap in the rock face like a mouth that never closed, the narrow passage that turned twice before it widened, the way the world’s noise died at the threshold.

When Copper’s hooves suddenly changed sound, the dull crunch of snow giving way to the sharper knock of stone, Logan’s chest loosened by a fraction.

Then, through the swirl, he saw it: a black seam splitting the white wall, the cave entrance yawning open as if it had been waiting for him and no one else.

He swung down, grabbed Copper’s reins close, and half led, half dragged her through the gap. The moment they crossed into the passage, the wind’s scream collapsed into a muffled roar, like a monster shoved behind a door. The air changed too, no longer a knife but a deep, steady chill that didn’t climb into the bones with the same malice. Logan’s breath steadied as if his lungs recognized sanctuary.

Copper’s head lifted. Her nostrils flared. She whickered softly, confused by the sudden absence of violence.

“That’s it,” Logan murmured, voice low now that he could hear his own thoughts again. “That’s the difference.”

He guided her deeper, past the first bend where the entrance light became a pale smear, past the second where darkness thickened and the cave’s old smell rose: mineral dampness without rot, cold stone without decay, a faint sweetness from the spring deeper in. He struck a match with fingers that still obeyed, lit a lantern, and watched the flame settle as if it too had been relieved to stop fighting.

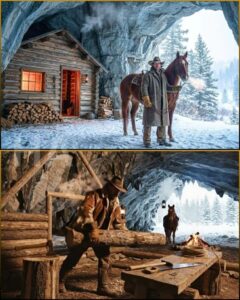

The chamber opened around them like the inside of a cathedral carved by time instead of hands, the ceiling arched high and the walls curved in pale limestone ribs. In that chamber, set back from the entrance like a thought protected behind the mind’s front teeth, stood Logan’s cabin.

A full log cabin inside a cave.

A year’s worth of work, a year’s worth of splinters, a year’s worth of laughter from other people.

They had called it McKenna’s Cave Castle, Hermit’s Hole, Bear House, the kind of names men made when they needed to pretend they were not worried by someone else’s certainty. They had laughed the way people laugh at a man building a lifeboat in dry weather.

Logan didn’t smile as he led Copper toward the small stable he’d built beside the cabin, yet something like satisfaction moved behind his ribs when he felt the cave’s steady air wrapping around them. He threw blankets over Copper’s steaming back, checked her legs, her hooves, her flanks for injury, then pressed his forehead briefly against her shoulder.

“You trusted me into the dark,” he whispered. “I won’t spend that trust cheap.”

Outside, the blizzard began its five-day siege.

Inside, the cabin’s window showed the entrance as a distant rectangle of white fury, and Logan McKenna, the man everyone had called foolish, fed kindling into his stove with hands that had stopped shaking. He listened to the storm batter stone that had been standing for millions of years, and he knew, with the calm that comes only from preparation, that the world could rage as much as it liked. It could not reach him here.

To understand why he had ever chosen this place, why he had been willing to live under the weight of rock and rumor, you had to rewind to the season when the valley still smelled of thaw and new grass, when men in Silver Ridge still had enough daylight in their lives to waste some of it on ridicule.

Logan arrived the previous fall with railroad money in his pockets and silence in his manner, a tall man with a weathered face that didn’t look old so much as edited by wind. He bought the Callahan property not because it was pretty, not because it promised crops, not because it offered the kind of flat land people liked to imagine under a future house, but because it held a cave system tucked into limestone like a secret too stubborn to be dug out.

At the county office, Sheriff Morrison watched Logan sign the deed with an expression that had started as routine and shifted toward disbelief.

“Callahan land,” Morrison said, as if saying the name might transform it into something more sensible. “Twenty acres of rock and a hole in a hill.”

“It’s a fine hole,” Logan replied, pen scratching steady.

Morrison leaned back. “You planning to dig for treasure, McKenna?”

Logan’s mouth twitched, almost a smile. “I’m planning to stop fighting the weather.”

“Weather’s a thing we all fight,” Morrison said, half joking, half serious. The sheriff had a thick mustache and the kind of weary eyes that came from a job built on other people’s trouble. “You’ll build up on the south slope like everyone else if you’ve got any sense.”

Logan capped the ink. “I’ll build inside.”

Morrison blinked. “Inside what?”

“The cave.”

Silence thickened between them in the little office that smelled of paper and old coffee. Morrison’s eyebrows rose slowly, like a curtain lifting on a show he wasn’t sure he wanted to watch.

“You mean,” he said carefully, “you’re telling me you plan to live in a cave.”

“I plan to live in a cabin,” Logan corrected, voice patient. “The cabin will be inside the cave.”

Morrison let out a short laugh, the kind that escaped before a man could decide whether he meant it. “Well, I’ll be. Folks are going to enjoy hearing that.”

They did.

Silver Ridge was a town that survived on timber, cattle, and gossip in roughly equal measure. Within a day, the saloon’s regulars were slapping tables, Mayor Harold Thompson was shaking his head like he’d been handed evidence of civilization’s decline, and Victoria Hansen, who ran the general store with a spine as stiff as her starched collars, was declaring to anyone who would listen that a cave was no place for a decent human being.

“Dark,” she pronounced, ringing up nails for Thomas Brennan the builder. “Damp. Full of bats and disease.”

Thomas shrugged, heavy hands resting on the counter. “Caves are dry sometimes.”

“Sometimes,” Victoria allowed, as if granting him a crumb. “Even if it’s dry, it’s still underground. People don’t live underground unless they have to.”

Logan walked in while she spoke, snowmelt dripping from his boots, and the bell above the door announced him like a challenge. He nodded at Thomas, then at Victoria.

“I’m here for hinges,” he said, placing coins on the counter with neat precision. “And a pane of glass if you still have one that isn’t cracked.”

Victoria’s eyes narrowed. “Glass. For your… cave.”

“For my window,” Logan said, unruffled. “Light is useful.”

“And you’re not worried,” she asked, voice sharpened by curiosity and disapproval, “about what might be living in there already?”

Logan considered her question as if it deserved respect, which irritated her more than dismissal would have. “I’m worried about what’s living out here,” he said at last, glancing toward the mountains. “Wind doesn’t care about decency.”

Mayor Thompson cornered him at the town meeting held in the church, the wooden pews filled with men who smelled of sawdust and women who smelled of soap, all of them hungry for an evening’s entertainment.

“Mr. McKenna,” the mayor boomed, spreading his hands. “We’re a community here. We look out for each other. We don’t want to see anyone throw their money into a pit.”

“It’s limestone,” Logan replied. “Not a pit.”

Laughter fluttered through the room. Logan waited it out without flinching.

“Why,” Thompson pressed, “would a man choose to hide in a cave like some kind of outlaw?”

Logan’s gaze moved across the faces. He saw amusement, he saw suspicion, he saw fear hiding behind the amusement like a child behind skirts. He also saw the practical worry of people who had buried neighbors after bad storms, who knew winter was not a story but a verdict.

“Because caves hold steady,” he said, voice carrying without strain. “Stone doesn’t shiver. Temperature stays near the same year-round. Wind can’t pry at the seams of something that has no seams. Snow can pile until it blocks the sun, and the cave doesn’t notice.”

“That sounds like a sermon,” someone muttered.

“It’s mathematics,” Logan said. “Thermal mass. Airflow. Shelter.”

Victoria stood, chin lifted. “And what about flooding? I’ve heard caves fill like bowls.”

“The chamber I’m using sits above the drainage line,” Logan replied. “The spring flows deeper, away from the main room. I spent two days mapping water tracks after rain. Water passes it. It doesn’t collect.”

“Cave collapse,” another voice called, eager for a dramatic objection.

Logan nodded once. “Limestone caves that have stood for millennia don’t suddenly decide to fall unless you weaken them. I’m not blasting. I’m not digging pillars out. I’m building inside what already exists.”

Mayor Thompson smiled in the way a man smiles when he believes the room is already on his side. “So you’ll live in the dark, then, and call it progress.”

Logan’s answer came quiet. “I’ll live where winter can’t get its hands on my throat.”

That silenced the laughter, not because they understood him, but because the image had stepped too close to something real.

They mocked him anyway.

When Logan began hauling logs and tools to the hillside, children followed at a distance, daring each other to shout “Caveman!” before running off. Men at the saloon invented wilder stories after each drink: Logan was building a secret hideout, Logan was hoarding gold, Logan was running from a woman, Logan was running from the law. Women who had never stepped inside the cave described it as if they had grown up there.

Logan worked through the noise. He cleared loose rock, leveled the cave floor, checked the ceiling with the careful eye of someone who had once watched an avalanche bury a line of men like spilled pins. He measured, marked, and began building a cabin that stood inside the cave like a stubborn idea inside a skeptical mind.

He chose logs thick enough to resist years of use, not because the cave demanded it but because he did not believe in temporary shelter. He notched corners tight, sealed gaps, built a roof with a shallow pitch, and fitted it beneath the arch of stone so that even if the cave wept a little in spring, the water would slide away instead of soaking his life.

He carried in a real door, iron latch, sturdy frame. He carried in glass for two windows facing toward the entrance so daylight could reach him without him needing to invite the weather inside. He built storage into natural alcoves, turning hollows in the limestone into cupboards. He dug a small root cellar chamber farther back where the air stayed even colder, a place where potatoes and smoked meat could rest without spoiling.

His chimney was the part he loved most, though he never said so. The cave ceiling held a narrow natural vent that ran like a throat to the surface, unseen from the valley. Logan tested it with smoke in calm weather, in wind, in rain, watching how the draft changed, how the cave breathed. He adjusted his stove pipe, built a seal, and when the smoke rose properly, drawn upward by the cave’s own quiet physics, he felt a rare kind of joy, the joy of fitting human need into natural design without breaking either.

Copper’s stable came last, built beside the cabin with a half wall and a hay loft, enough room for her to turn and lie down, enough shelter that predators and cold became rumors instead of threats. Copper followed him through every stage, patient as stone, nose nudging his shoulder when he paused too long, as if reminding him that work was less frightening when it continued.

Thomas Brennan visited once, hands shoved into his pockets, eyes tracing the structure like a man studying a puzzle.

“You’re serious,” Thomas said.

Logan kept hammering. “I haven’t been pretending.”

Thomas scratched his beard. “It’s… clean. For a cave.”

Logan glanced at him. “You expected filth.”

“I expected madness,” Thomas admitted, then cleared his throat as if honesty had escaped without permission. “You’ve thought about everything.”

“Not everything,” Logan said, smiling faintly. “Only what can kill me.”

The cabin took all summer and into fall. By the time the first hard frost painted the meadow grass brittle white, Logan moved in.

The town waited for collapse, for illness, for a scream in the night.

None came.

Logan thrived in a way that made their jokes feel less secure. He used less firewood than his neighbors because the cave didn’t steal heat with wind. He slept without hearing shingles rattle. He woke to mornings where the outside world might be howling, yet inside the cave air remained steady, indifferent. He still rode into town for supplies, still nodded hello, still spoke when spoken to, yet he carried a calm that made some people uneasy, because calm looks like arrogance when it cannot be shaken.

Victoria watched him with a frown that had layers. One afternoon, after he paid for flour and lamp oil, she said, quieter than usual, “Don’t you get lonely out there?”

Logan paused, coins in hand. His eyes lifted to meet hers, and for a brief moment the store seemed to hold its breath.

“I get quiet,” he said. “Lonely is different.”

She didn’t have a reply ready, which annoyed her, so she turned to straighten jars that were already straight.

Winter deepened. The river stiffened. Silver Ridge wrapped itself in smoke and routine. Then, the week before Christmas, the barometer began to fall in earnest.

Logan felt it in the cave first because he paid attention. The cave breathed differently when pressure changed, the airflow shifting in faint currents that tickled the flame of his lamp. Copper grew restless, pacing her stall, ears flicking, tail swishing at nothing. Birds disappeared from the scrub trees outside the entrance. The air in town took on a metallic edge that made the back of the throat sting.

Sheriff Morrison knocked on Logan’s cabin door the day before the blizzard, having ridden out with his collar turned up and his hat pulled low.

“You heard the forecast?” Morrison asked, stepping inside and glancing around as if expecting the cave to lunge at him.

“I don’t need a forecast,” Logan said, pouring coffee. “The mountain’s been clearing its throat.”

Morrison accepted the mug like a man accepting an unfamiliar truce. “Mayor says it’ll blow over.”

“Mayor says a lot,” Logan replied.

Morrison hesitated. “If it’s bad, I might bring my family up here.”

Logan’s gaze softened slightly. “If it’s bad, bring anyone who can make it.”

Morrison frowned. “You’d do that? After… you know.”

After the jokes. After the names. After the way people looked through Logan as if he were an inconvenience.

Logan sipped his coffee. “Weather doesn’t care who laughed.”

Morrison left with his shoulders tight, carrying gratitude he didn’t know how to show. Logan watched him go, then stood in the cave entrance passage for a long moment, studying the sky’s bruised color and listening to the wind’s growing impatience. He inventoried supplies in his head: beans, flour, jerky, oats for Copper, wood stacked dry, lantern oil, matches, blankets. He could last weeks if he needed to.

He did not know that the town, with all its roofs and chimneys and confidence, would struggle to last five days.

When the blizzard hit, it did so with the timing of betrayal.

People in Silver Ridge had been going about ordinary December business, repairing fences, hauling water, wrapping gifts for children who still believed in kindness as a guarantee. The first gust toppled a stack of firewood at the Cooper home; the second gust ripped a sign from the saloon wall; the third gust turned snow into a horizontal white sheet that slapped faces and stole breath.

Those who were outside ran, then stumbled, then crawled. Those inside discovered that walls were merely polite suggestions to a storm determined to enter.

By nightfall, the town became a cluster of dim lamps behind frosted panes, each home a small island of panic. Chimneys clogged where wind jammed snow down like packing a musket. Drafts hissed through cracks no one had noticed. Floors turned cold enough to punish bare feet. People burned more wood in one night than they had planned for a week.

Sheriff Morrison tried to organize assistance, yet the moment he stepped outside, the storm took him by the coat and threw him back against his own door. He could not reach the widow on the east edge of town who lived alone. He could not reach the Hansen store to check on Victoria and her younger brother. He could not reach the church, where Father Ellis had rung the bell until the rope froze stiff in his hands.

The storm didn’t merely cover the town; it pressed it down, smothering sound, forcing everyone to listen to the same roar, the same endless grinding scream of wind over snow, the voice of something ancient that had decided the valley belonged to winter again.

In the cave, Logan listened too, though the sound arrived softened by stone. He tended Copper, cooked, read by lamplight, and slept in stretches, his body trained by years of fieldwork to wake at the smallest change.

On the second day, he heard it: a difference in the storm’s rhythm, a brief lull followed by a heavier rush, as if the wind had turned its attention. Copper stamped hard enough to rattle her stall boards, and Logan sat up, alert.

He waited, breath held, hearing only the cave’s quiet and the storm’s muffled fury.

Then a sound reached him that did not belong to weather.

A dull knock, faint and irregular, carried through the entrance passage like a desperate heartbeat.

Logan moved fast, lantern in hand, boots barely whispering on the packed cave floor. He reached the passage and paused, listening. Another knock came, followed by a thin, broken sound that might have been a voice or might have been imagination.

He leaned forward into the dark mouth of the entrance, where the blizzard’s light glowed dimly.

“Hello!” he shouted.

The wind ripped the word away, yet something answered, a weak cry swallowed by white.

Logan’s mind ran through the possibilities with ruthless speed. Someone from town. Someone lost. Someone foolish enough to leave shelter. Someone desperate enough to bet their life on his “Hermit’s Hole.”

If he went out, the storm might take him too. If he stayed in, a human being might freeze within steps of safety.

He thought of the winter years ago on the railroad line, the way his partner, Caleb, had insisted they could make camp under a shallow overhang instead of climbing farther to reach a rock shelter. Logan had argued. Caleb had laughed. Night had come, and with it wind that seemed to hate them personally. In the morning, Caleb’s eyes had been open, his face pale and stunned, as if still surprised the world could be so indifferent.

Logan had carried that look inside him ever since, a frozen thing he could not thaw, a debt he did not know how to pay.

He did not allow himself to hesitate now.

He grabbed the coil of rope he kept by the passage wall, looped it around his waist, anchored the other end to a steel ring set into stone, then wrapped a scarf tighter around his face. The lantern flame wavered as cold air surged toward it from outside, and Logan shielded it with his hand.

Copper whickered behind him, anxious.

“I’ll be back,” he told her, as if she were the one who needed logic.

He stepped into the blizzard.

The wind hit like a thrown door. Snow struck his face, found the gaps, clawed for skin. Visibility shrank to a couple of feet, and the world beyond that became a blank roar. Logan kept one hand on the rope, the other reaching forward, feeling for shapes.

“Follow the rope,” he muttered to himself, voice lost. “Count your steps. Don’t let the white make you stupid.”

A shadow appeared, low and collapsed near a drift, half buried. Logan dropped to his knees, snow instantly filling his sleeves, and dug with gloved hands until he found cloth, then a shoulder, then a human body.

A boy, maybe sixteen, face crusted with ice, lips blue, eyelashes white. Logan recognized him even through the storm: Eli Thompson, the mayor’s oldest, the one who liked to swagger past the saloon with a cigarette he wasn’t old enough to buy.

Eli’s eyes fluttered open, unfocused. His mouth moved.

Logan leaned close, caught a whisper. “Medicine,” the boy rasped. “My little sister… fever… couldn’t… breathe…”

Logan’s gut tightened. The Thompson child, Lucy, had been sick earlier in the week; Victoria had mentioned it with a dismissive sniff that couldn’t hide worry.

“How many?” Logan shouted.

Eli’s gaze shifted past Logan’s shoulder, and Logan turned, squinting into the white. Shapes moved there, stumbling, falling, rising again. Three figures, hunched, bound together by desperation.

Logan hauled Eli upright, slung the boy’s arm over his shoulder, and grabbed for the others as they reached him: Victoria Hansen, hair loose beneath her hood, cheeks raw with cold; Lucy, a small bundle in Victoria’s arms, limp and frighteningly still; Father Ellis, bent and shaking, one hand clutching his chest as if keeping his heart from escaping.

Victoria’s eyes met Logan’s. Her face held terror, stubbornness, and something like shame, all jumbled together as if she had been forced to carry more than her body could organize.

“The chimney,” she tried to say, but her lips barely worked. “Smoke… Lucy couldn’t…”

Logan didn’t waste breath on questions. He tightened his grip on Eli, took Lucy’s bundle from Victoria with gentle urgency, and nodded toward the cave’s black mouth behind him.

“Hold the rope,” he barked, pushing Victoria’s hand to it. “One hand on me if you can manage. You don’t let go.”

They moved as one clumsy creature, the rope their lifeline, the cave’s entrance a dark promise that seemed impossibly far even though it was only steps. The wind pushed them sideways, tried to separate them, yet Logan’s anchored line resisted. He pulled, staggered, pulled again, and the moment the passage swallowed them, the sound of the blizzard dulled, and the cold loosened by a fraction, as if the cave were refusing winter’s violence.

Inside the main chamber, Logan carried Lucy straight to the stove, laid her on blankets, and began rubbing her hands, her feet, her cheeks, careful not to shock frozen skin with sudden heat. Victoria collapsed to her knees beside her, shaking, tears carving lines through frost on her face. Father Ellis sank onto a stool, wheezing, while Eli slumped against the wall, eyelids heavy.

Logan moved like a man whose body knew what his mind could barely endure. He fed the stove, warmed water, mixed a small amount of whiskey into a cup for Eli and Father Ellis, forced them to sip, then peeled Lucy’s damp layers away and replaced them with dry cloth, his hands steady because panic never helped a dying child.

“Breathe,” he told Lucy softly, though she did not respond. “Come back up. You’re not done.”

Victoria watched him with wild eyes. “She’s… she’s—”

“She’s cold and sick,” Logan said, voice firm. “Not gone. Not yet.”

He pressed an ear to Lucy’s chest, listened for the thin stubborn flutter. It was there, faint as a moth wing.

“Good,” he murmured, relief sharp enough to hurt. He glanced at Victoria. “You made it here. That counts for something.”

Victoria’s mouth trembled. “I didn’t know where else to go.”

Logan didn’t answer with “You should have known.” He didn’t answer with “You laughed at me.” He didn’t answer with anything that would make her feel smaller, because a blizzard already had.

He answered with action: more blankets, more warmth, more steady attention.

For a while, the cave cabin became a small island of human breath and fire in a world determined to extinguish both. Lucy’s fever fought the cold, the cold fought her lungs, and Logan sat by the stove with a damp cloth, wiping her forehead, coaxing water between her lips in tiny sips.

Eli began to shiver harder, and Logan guided him to the stable area where Copper’s body heat added warmth to the air. The mare sniffed Eli’s hair and huffed, as if accepting him into her strange stone herd.

Father Ellis looked around the cabin, eyes lingering on the log walls, the windows, the carefully placed supplies, the quiet order. “It’s… a home,” he whispered, sounding surprised.

Logan handed him another cup. “Yes.”

“And you built it,” the priest said.

Logan’s gaze stayed on Lucy. “Yes.”

Father Ellis’s voice grew rough. “I told them your pride would be punished.”

Logan finally looked at him, eyebrows lifting. “My pride?”

Father Ellis swallowed, then managed a weak, embarrassed smile. “Perhaps I have used the wrong word.”

Logan’s answer was gentler than it might have been. “People call preparation pride when they feel unprepared.”

The third day arrived without sunrise, because the storm had stolen the sky. The roar continued, relentless. Snow sealed the cave entrance almost to the top, and Logan realized it not by looking out but by feeling the cave’s airflow change again, the passage breathing more slowly. He went to the entrance, lantern lifted, and saw a wall of packed snow pressed against the outside like a fist.

A cave could not be buried the way a house could, not entirely, yet an entrance could be blocked, and a blocked entrance could suffocate a refuge if the air exchange failed.

Logan stood there, thinking, feeling the weight of responsibility settle heavier than the rock overhead.

Behind him, Victoria slept in a chair by Lucy’s blankets, exhaustion forcing her into stillness. Eli lay on the floor with Copper’s spare blanket thrown over him. Father Ellis muttered prayers in his sleep, words drifting like ash.

Logan returned to the cabin, opened the small hatch he had built into the cabin’s wall, and checked the ventilation channel he had carved to connect with a narrower crack deeper in the cave system. He had built it months ago as a precaution, an insurance policy against smoke backdraft or a blocked entrance, and now it mattered.

He adjusted the flue, tested airflow with a strip of cloth, watched it tug gently toward the crack.

Air.

Good.

He returned to the passage with a shovel and began digging a narrow trench through the entrance snowpack, not to clear it fully, which would be impossible while the storm raged, but to create a breathing channel, a small throat the cave could use to exchange air without allowing the full violence of the blizzard inside.

He worked for hours, muscles burning, face numb, pausing only when his breath began to rasp too harshly in the cold pocket near the entrance. Stone behind him held steady warmth; snow ahead held lethal cold. He carved the line between them like a man drawing a boundary around life.

When he finally stepped back, a narrow tunnel to the surface open just enough to let wind hiss through without sealing entirely, he rested his forehead against the limestone and closed his eyes.

“Not today,” he whispered to winter. “Not in my house.”

The fourth day tested them in a different way.

Lucy’s fever broke in the early hours, sweat soaking the cloth Logan had placed on her chest, her skin warming to a human temperature again. Victoria woke to find her sister’s eyes open, glassy but alive, and the sound Victoria made was not quite a sob, not quite laughter, but something raw that tore free of the person she usually pretended to be.

“She’s back,” Victoria breathed, pressing her face into Lucy’s hair.

Logan watched quietly, feeling the tight band in his chest loosen. He was not a doctor, yet he knew enough to keep a child warm, hydrated, and breathing; he knew enough to make shelter behave like a second set of lungs.

Eli, embarrassed by his own vulnerability, tried to stand too quickly and nearly fell. Copper snorted as if scolding him. Logan steadied the boy.

“You did something foolish,” Logan said.

Eli’s cheeks reddened, though cold had already made them raw. “I had to.”

Logan studied him, seeing the fear behind the bravado, the love behind the recklessness. “Next time, do something foolish with a rope and a plan.”

Eli swallowed. “Yes, sir.”

Victoria watched the exchange, eyes softer than Logan had ever seen them. “You could have left us,” she said, voice low. “You could have let the storm take what it wanted.”

Logan didn’t pretend the thought hadn’t existed. “I’ve seen what storms take,” he replied. “I don’t enjoy giving them help.”

She nodded, understanding without needing more.

The blizzard finally broke on the morning of the sixth day. Logan woke to silence so complete it felt wrong, as if the world had died in its sleep. He went to the entrance passage and saw pale blue light filtering through the trench he had dug, the snow outside no longer moving like an army but sitting heavy and still.

He opened the passage enough to look out.

The valley was unrecognizable. Drifts rose like frozen waves. Fence posts vanished. The town, five miles away, was hidden behind a white ridge line, smoke absent because wind no longer carried it and because, Logan suspected, many chimneys had failed.

He turned back to the cabin.

“We’re going to town,” he said.

Father Ellis looked up, eyes red. “People will be dead.”

“Yes,” Logan said, voice flat with certainty. “And people will be alive and in trouble. We go.”

Victoria stood, stiff, pulling Lucy close. “I’ll come.”

Logan shook his head. “Lucy stays here with Copper and Father Ellis while we check the town. She’s not walking through that.”

Victoria’s mouth tightened, yet she nodded, because the storm had already taught her that stubbornness without sense was just another way to die.

Eli insisted on riding with Logan. His pride demanded it; his conscience demanded it more. Logan didn’t argue, because sometimes a boy became a man through doing the hard thing after fear, not before.

They saddled Copper, the mare stepping out of the cave like someone emerging from a strange dream. Logan led her carefully down the drifted slope, choosing routes by memory and by the way snow settled around rocks. The world glittered under weak winter sun, beautiful in the way a knife could be beautiful.

The ride to Silver Ridge took twice as long as it should have. In places, drifts rose taller than Copper’s chest, and Logan had to dismount, pack snow, find firmer ground. They passed a wagon half buried, its wheels sticking out like broken bones. They passed a tree snapped in half, its splintered heart exposed.

When the town finally emerged, Logan’s stomach tightened.

Silver Ridge looked like a place that had been punched. Roofs sagged. A corner of the church had collapsed inward, the bell tower leaning slightly as if exhausted. The saloon sign lay buried, only the edge of the painted “S” visible. Smoke rose from some chimneys, thin and weak. Others were silent.

People moved slowly in the streets, bundled like ghosts, faces hollow, eyes wide with the stunned look of survivors who hadn’t decided yet whether they deserved survival.

Sheriff Morrison stumbled out of a drifted alley and froze when he saw Logan.

For a moment Morrison stared as if Logan were a hallucination created by hunger. Then he rushed forward, boots sinking, and grabbed Logan’s arm.

“McKenna,” he rasped. “You’re alive.”

Logan nodded. “So are you.”

Morrison’s eyes flicked to Eli. “Eli Thompson? Lord help us, we thought—”

“I’m here,” Eli said, voice hoarse, guilt flashing across his face.

Morrison’s gaze returned to Logan, questions tumbling. “How? How did you—”

“The cave,” Logan said simply.

Morrison looked past him toward the hills as if he could see through distance and snow to the shelter hidden inside stone. His face tightened. “We lost seven,” he said, voice breaking on the number. “Old Mrs. Parson froze before we could get her moved. The Cooper baby… and two men out by the sawmill. We couldn’t reach them.”

Logan’s jaw clenched. “Who needs help now?”

Morrison blinked, as if he hadn’t expected that question to be the first one. “Half the town,” he said. “Food’s low. Firewood’s wet where sheds collapsed. Injuries… frostbite… roofs.”

Logan swung down from Copper. “Then we start with the living.”

What followed was not a heroic speech, not a grand moment of forgiveness, but work, the kind that built towns in the first place. Logan and Eli helped dig out doors, cleared chimneys, hauled firewood from Logan’s own stores back at the cave for families who had burned through theirs. Logan guided Morrison to the cave entrance later that day, leading a small group of the most vulnerable: an elderly couple whose house had lost its roof, a mother with two infants, a man with an infected wound that needed warmth and clean air more than it needed bravery.

When they reached the cave and stepped inside, the group fell silent. The way the wind died at the entrance felt like stepping out of war and into a church. The warmth that lingered in the stone seemed impossible after five days of cruelty.

Victoria, watching them arrive, rose from her chair, eyes meeting Logan’s across the chamber. Her gaze held gratitude, shame, and something else too: respect that had finally found a place to live.

Over the next weeks, the cave became what Logan had always known it could be, though he had never admitted to himself that he wanted it to matter to more than one life.

Mayor Thompson came to the cave on unsteady legs, his face drawn, his eyes red-rimmed. He stood in Logan’s cabin doorway, hat in hand, pride stripped down to bare human bone.

“I owe you,” Thompson said.

Logan didn’t let the mayor off easily with a simple apology, though he also didn’t humiliate him. “You owe the town,” Logan replied. “You owe them planning instead of hoping.”

Thompson swallowed. “Will you… will you let this place be a refuge? Officially. For everyone.”

Logan looked around at the sleeping platforms he had begun building out of spare lumber, at the shelves where he’d moved supplies to make room for more bodies, at Copper’s stable where children now patted the mare’s neck with cautious awe.

“It can be,” Logan said. “If it’s respected. If it’s kept stocked. If it’s treated like the tool it is, not a novelty.”

Thompson nodded quickly. “We’ll do it. I swear we will.”

Logan’s voice hardened slightly. “Swearing isn’t enough. Put it in writing. Put it in practice.”

The town council did. They voted to compensate Logan for supplies used in emergencies, to maintain a stored cache of food and blankets in the cave, to build a marked path to the entrance with poles tall enough to show above drifts, and to assign responsibility by rotation so the refuge did not rest solely on one man’s shoulders.

Thomas Brennan began visiting often, not with jokes but with notebooks. He studied Logan’s chimney design, his airflow channels, the way the cabin sat back from the entrance to create a buffer zone. He began incorporating the principles into new buildings: bermed walls, sheltered orientations, windbreaks planted in thick lines.

“You weren’t wrong,” Thomas admitted one evening as they sat by the stove. “You were just early.”

Logan looked at him over his coffee. “Early and wrong look alike from a distance.”

Victoria changed too, though her transformation came in smaller, sharper increments. She began stocking extra emergency supplies in the store and labeling them clearly, no longer trusting luck. She organized a winter committee that checked on elderly neighbors before storms. She brought Lucy to the cave on clear days, the girl’s laughter echoing off stone like a bell that refused to freeze.

One afternoon, while Lucy fed Copper an apple slice, Victoria stood beside Logan near the cabin’s window, watching light spill through the entrance and paint pale bands across the floor.

“I said it wasn’t civilized,” Victoria murmured, voice tight with memory.

Logan didn’t pretend he didn’t remember. “You did.”

“And yet,” she continued, eyes on her sister, “it saved her.”

Logan’s gaze softened. “Stone doesn’t care about our opinions.”

Victoria exhaled slowly. “I do,” she said. “I cared too much about being right.”

Logan let the silence sit between them until it became something gentler. “Most people do,” he said.

“What made you different?” Victoria asked, turning to face him fully. “Why did you build this when everyone told you not to?”

Logan’s hand rested on the window frame, rough wood under his palm, the kind of texture that reminded him he was still human and not entirely stone. He considered lying, giving her a simple answer, yet he had seen her hold her sister’s limp body through a blizzard; she had earned something real.

“I watched a man freeze because we chose the wrong shelter,” Logan said quietly. “I promised myself I’d never let weather decide for me again.”

Victoria’s expression shifted, sorrow flickering. “I’m sorry.”

Logan nodded, accepting it the way a man accepted warm fire after cold. “So am I.”

Years passed. Silver Ridge rebuilt, not into a grand city, not into something that could pretend winter didn’t exist, but into a town that understood humility. The cave refuge became part of the community’s rhythm. Before hard storms, families brought the elderly and the very young up the marked path, not with panic but with practiced efficiency. The cave held laughter, arguments, prayers, songs, the messy human sounds of life continuing in a place the wind could not reach.

Logan stayed mostly as he had always been: quiet, watchful, respectful of the mountain’s moods. He was less alone, though. Children stopped by on summer days to ask about the cave’s spring. Men came seeking advice on building windbreaks. Women brought pies and left them on his porch without needing to explain the gesture.

Copper aged, her muzzle whitening, her gait slowing. Logan cared for her with the same steady tenderness she had always given him. When she finally lay down one winter night and did not rise, Logan sat beside her for a long time, hand on her neck, listening to the cave’s deep quiet and letting grief move through him without hurry.

The town came to help bury her, a procession of boots and bowed heads through falling snow that seemed, for once, gentle. Lucy placed a small braided ribbon in the grave, tears on her cheeks.

“She trusted the dark,” Lucy whispered.

Logan looked down at the fresh earth. “She trusted me,” he said, voice rough. “The cave was just honest.”

When Logan grew old, the cave grew old with him, the logs darkening, the porch boards worn smooth by years of feet, the stone unchanged. A journalist arrived one spring, notebook in hand, eyes bright with the hunger for a good story.

“They say you were mocked,” the journalist said, sitting at Logan’s table while sunlight pooled through the window. “They say you built this and made fools of everyone.”

Logan smiled faintly, a quiet expression that held more patience than triumph. “They mocked what they didn’t understand,” he said. “I wasn’t trying to make fools. I was trying to make shelter.”

“Did you ever doubt yourself?” the journalist pressed.

Logan’s gaze drifted toward the entrance, toward the valley beyond, toward the town that had once laughed and had later learned to listen. “Every man doubts,” he said. “Doubt keeps you checking your work. Confidence keeps you finishing it. I had both.”

The journalist scribbled. “And living apart from town, did you regret it?”

Logan’s voice stayed calm. “I didn’t live apart,” he said. “I lived deeper. There’s a difference.”

When Logan McKenna died, it was in his bed with a lamp still burning low, the cave’s air steady around him, the spring’s distant murmur like a lullaby that had been singing long before he arrived. Silver Ridge held a service in the church that had been rebuilt stronger, its windows thickened, its walls braced. Then they carried him up the marked path to the cave, because it felt wrong to leave him anywhere else.

Thomas Brennan, now gray-haired, hammered a plaque at the entrance after the burial. Victoria, older and gentler, stood beside Lucy, now grown, her hand resting on her sister’s shoulder.

The plaque was simple, because Logan would have hated poetry carved into stone for show. It read:

LOGAN McKENNA’S REFUGE

MOCKED AS MADNESS

PROVEN AS MERCY

Beneath it, Lucy mounted an old horseshoe on the stable wall where Copper had once stood, and beneath the horseshoe she wrote, in careful letters that shook only a little:

COPPER

WHO FOLLOWED INTO DARKNESS

AND FOUND A HOME

Every winter after that, when the barometer fell and the sky bruised, Silver Ridge no longer relied on hope alone. They relied on planning, on shared responsibility, on the lesson carved into limestone and memory: that unfamiliar ideas often look foolish until the moment they become necessary, and that the people we laugh at are sometimes the ones building the thing that will save us.

The cave still stands, indifferent to praise, immune to mockery, holding steady under storms that come and go like tempers. The cabin inside it has been repaired and re-repaired, logs replaced when time finally asked for its due, windows re-glazed, platforms rebuilt. The stone above remains what it has always been: ancient, patient, stronger than any argument in a saloon.

On quiet days, when children wander up the path and step into the entrance passage, they pause the way people always pause when they cross from wind into shelter. They feel the air change, feel the world’s violence stop at the threshold, and they learn, without anyone needing to lecture them, that wisdom does not always look civilized at first glance, and that sometimes the safest way to live is not by standing taller against winter, but by choosing to shelter deeper where winter cannot reach.

News

The MILLIONAIRE’S BABY KICKED and PUNCHED every nanny… but KISSED the BLACK CLEANER

Evan’s gaze flicked to me, a small, tired question. I swallowed once, then spoke. “Give me sixty minutes,” I said….

Can I hug you… said the homeless boy to the crying millionaire what happened next shocking

At 2:00 p.m., his board voted him out, not with anger, but with the clean efficiency of people who had…

The first thing you learn in a family that has always been “fine” is how to speak without saying anything at all.

When my grandmother’s nights got worse, when she woke confused and frightened and needed someone to help her to the…

I inherited ten million in silence. He abandoned me during childbirth and laughed at my failure. The very next day, his new wife bowed her head when she learned I owned the company.

Claire didn’t need to hear a name to understand the shape of betrayal. She had seen it in Daniel’s phone…

The billionaire dismissed the nanny without explanation—until his daughter spoke up and revealed a truth that left him stunned…..

Laura’s throat tightened, but she kept her voice level. “May I ask why?” she said, because even dignity deserved an…

The Nightlight in the Tunnel – Patrick O’Brien

Patrick walked with his friend Marek, a Polish immigrant who spoke English in chunks but laughed like a full sentence….

End of content

No more pages to load