The auctioneer’s voice didn’t just sound tired. It sounded offended, like the day itself had personally wronged him and he’d been arguing with the sun for hours. “Last chance,” he barked, slapping his ledger as if it might produce mercy by force. “Anybody?” Heat shimmered above the town square in Red Hollow, Wyoming, turning the crowd into a wavering mirage of hats, squinting eyes, and impatience. On the wooden platform, a child stood as still as a fence post, too small to be useful, too quiet to be entertaining, too thin to make anyone feel generous. Her dress was mostly seams holding onto a memory of fabric, and her bare feet—dust-caked and raw—pressed into the rough boards like she was trying to disappear into the grain.

She clutched a torn teddy bear against her chest with both arms, as if it were the only law left in her world. The bear’s ear was missing, one button eye hung by a thread, and yet she held it like a crown. The child’s hair was pale, tangled into knots that looked like they’d been pulled tight and abandoned, and her face was all hollows and enormous brown eyes. Those eyes didn’t beg. They didn’t accuse. They simply watched, calm in a way that made grown men shift their boots and look away. Crying, she’d learned, was an invitation for someone to prove you wrong for having hope.

Someone in the crowd muttered, “Worthless,” and it wasn’t said like a cruelty, but like a measurement. A farmer with sunburned arms shook his head. “Too small. Be years before she’s useful.” A woman beside him pressed her lips together, pity fighting with hunger. Another voice, sharper, said, “Damaged goods,” and laughter tried to follow but died halfway, embarrassed by itself. The auctioneer wiped his brow, desperate now. “She eats almost nothing,” he called, as if starvation could be spun into a bargain. “Won’t be no burden at all. Just needs a roof and scraps.”

That was when boots struck the platform. Not hurried boots. Not curious boots. Boots that belonged to a man used to having the ground remember him. A tall figure stepped out of the shade at the edge of the crowd, and for a moment the square held its breath. Caleb Mercer didn’t look like the kind of man who attended public spectacles unless he meant to end one. Broad-shouldered, sun-browned, wearing a clean shirt that still carried the honest wrinkles of work, he moved with the quiet certainty of someone who had made a habit out of surviving. The Mercer Ranch sat ten miles outside Red Hollow, and everyone in town knew it as the biggest spread for two counties. They also knew Caleb as a widower who kept to himself, a man who’d gone hollow in private and built walls so high even friendly conversation couldn’t climb them.

He hadn’t come to town for this. He’d come for a stallion. That was what he kept telling himself as he walked, like repetition could rewrite fate. His foreman, Hank Doyle, had mentioned the placement fair in passing, the way men mention storms they hope will miss them. “Orphan auction,” Hank had said, spitting tobacco into the dust. “Train dropped a whole load from back East. Folks looking for cheap hands, mostly.” Caleb had answered, “Not my concern,” the way he answered everything that might touch his heart. Four years of practice had made the sentence smooth in his mouth, and four years of grief had made it feel necessary.

But then he’d heard the auctioneer call the child “the last one,” and something inside him had shifted like a lock turning. Maybe it was curiosity, maybe it was a reckless moment of conscience, maybe it was the memory of his wife, Eliza, dying with her hand in his and a promise still unfinished between them. Grief had taught Caleb to treat love like a debt collector: inevitable, relentless, and always arriving at the worst time. He’d spent years building a life that avoided anything complicated, because complication was how you ended up on your knees in a bedroom with the world collapsing in your arms. Yet here he was, pushing through the crowd, closer and closer, until he could see the child’s feet and the way she favored one ankle without making a sound.

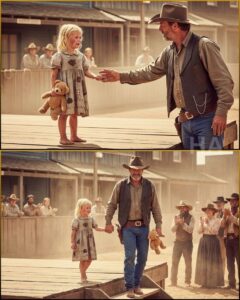

The auctioneer’s voice rose again. “Going once… going twice…” Caleb’s mouth moved before permission arrived from his brain. “Wait.” It came out rough, as if he’d dragged the word through gravel. Heads turned like sunflowers, hungry for drama. “Mr. Mercer?” the auctioneer blinked, startled. Caleb climbed the steps and the boards creaked under him, announcing his intent. Up close, the child’s smallness was worse than it had seemed from the ground. She wasn’t simply skinny; she was light in a way that suggested the world had been taking from her for a long time. When Caleb crouched, keeping his posture low, her body went rigid, not with fear of him exactly, but with the expectation that proximity always came with consequences.

“How much?” Caleb asked. The auctioneer hesitated, glancing at the crowd as if seeking approval to be honest. “The placement fee is five dollars,” he said, too quickly. Caleb pulled out his wallet, counted without flourish, and slapped fifty dollars onto the podium. The sound cut through the square like a gunshot. Whispering erupted immediately, sharp and delighted. A bachelor rancher buying a little girl. A rich man making a show. A scandal in the shape of a child.

“Papers,” Caleb said, voice steady now because steadiness was the one thing he could still do. The auctioneer thrust documents toward him, hands sweating, and Caleb signed without looking down for long. He didn’t want to miss the child’s face. Not because he wanted to study her like the crowd had, but because he wanted her to see that he wasn’t looking at her the way they were. “Hey,” he said softly, and the gentleness surprised him, like discovering water where you expected stone. “I’m Caleb. What’s your name?” She stared at him, jaw tight, the bear squeezed so hard its seams looked ready to split.

Caleb nodded toward the bear. “That your friend?” Her eyes flickered down, then up again. A spark, not trust, but something like recognition: yes, this is mine, and mine is all I have. Caleb waited, giving silence room to breathe. “I’ve got a ranch,” he continued, careful and calm. “Horses. A real bed. Food whenever you’re hungry. And nobody will hurt you there.” He didn’t say it like a promise meant to impress strangers. He said it like a vow he intended to live inside. The child watched him with a kind of fierce intelligence, as if she were measuring the distance between his words and his hands.

Finally, she nodded once. The smallest motion, the kind you’d miss if you blinked, but it hit Caleb like a fist to the chest. He reached out slowly. “I’m going to pick you up now,” he murmured, and he gave her time to pull away. She didn’t. She simply tightened around the bear and braced for impact. When he lifted her, she weighed almost nothing, a bundle of bones and held breath. Her body stayed rigid at first, waiting for pain that didn’t arrive, and Caleb felt a rage bloom so hot it scared him. Whoever had taught her to expect harm as the default had done something unforgivable.

He carried her through the crowd, and the whispers followed like gnats. “Ain’t natural,” someone said. “The church won’t like it,” another warned. Caleb didn’t look at them because if he did, he might do something he couldn’t take back. Hank was waiting by the wagon, eyes wide, mouth half-open with questions. “Caleb, what in God’s—” “Not now,” Caleb cut in, settling the child onto the seat with care for her battered feet. “We’re going home.” The child sat perfectly still, bear pressed to her chest, staring at the horizon as if the sky might offer instructions.

The ranch house appeared over the hill like a promise Caleb hadn’t earned. The fields lay gold and green beneath the Wyoming sun, horses scattered like moving coins, and the wind carried the clean smell of grass instead of sweat and judgment. On the porch, Edith Crowley stood with her hands on her hips, the household’s longtime keeper and Caleb’s closest thing to family. Her hair was pinned back, her apron dusted with flour, and her eyes sharpened when she saw what Caleb had brought. Not a new horse. Not a ledger. A child in rags with feet that didn’t belong on any stage.

“Lord above,” Edith breathed, and then the fierceness arrived, transforming her face as if she’d been built for this exact moment. “What have they done to that baby?” Caleb’s throat tightened, but he managed, “Nothing good.” Edith didn’t ask permission. She simply stepped forward, gentle as sunlight and deadly as a hawk. “Inside,” she said, voice like command and comfort wrapped together. “Now.” The child flinched at the sudden attention, but she followed Caleb through the doorway, moving like a shadow that didn’t believe it was allowed to exist.

In the kitchen, Edith set bread and cheese on the table, and Caleb watched the child eat as if she’d been punished for taking food slowly. She took tiny bites and swallowed fast, eyes tracking the room, memorizing exits. When Caleb reached out and rested two fingers on her wrist, not to stop her, but to anchor her, she froze hard enough to shake. He lifted his hand immediately. “You’re not in trouble,” he said quietly. “Nobody’s taking it away. There’s more.” Her eyes narrowed as if she suspected a trick. Caleb didn’t argue. He simply put more bread on the plate and sat down across from her, staying present like a piece of furniture that wouldn’t move.

When Edith called from the hallway that the bath was ready, the child’s entire body went rigid, and fear flared so fast it looked like anger. “No,” she whispered, the word sharp with memory. Caleb’s gut twisted, because fear of water didn’t come from nature. It came from someone making ordinary things dangerous. He crouched, meeting her eyes. “Okay,” he said, and he kept his voice steady even as his heart broke. “No bath tonight. We’ll go slow. You’re the boss of your body here. Nobody gets to force you.” The child stared at him like he’d spoken a foreign language, then blinked, and blinked again, as if she couldn’t find the punishment that should have followed defiance.

Edith prepared a small bedroom, clean sheets, a quilt stitched with blue squares, and a lamp that cast warm light instead of shadows. The child stood in the doorway and didn’t step in, as if entering would make it real and real things were always taken. “This is yours,” Caleb told her. “All of it. No one else’s.” She touched the quilt with one finger, then the dresser, then the window, pressing her palm against the glass like she needed proof the world could be solid. When she lifted her bear, uncertainty trembling in her voice, Caleb answered without hesitation. “Your bear too. Always.”

Late that night, Caleb stepped out into the yard and let the rage shake through him in silence. Edith had tried to change the child into a nightgown and had seen what lived beneath the rags: bruises in different colors, old marks that spoke of repeated harm. Caleb hadn’t asked for details, because he didn’t want the child to feel like a story being read. Still, the knowledge sat under his skin like a thorn. “I’m going to find out who did this,” he said to the dark, and the wind didn’t contradict him. Edith joined him after a while, her voice low. “Time,” she reminded him. “Patience. She needs proof more than promises.”

The proof began in small, stubborn ways. In the mornings, Caleb brought the child to the barn and introduced her to the horses, because horses understood fear without judging it. A gentle mare named Daisy had foaled two days before, and the baby’s nose was velvet-soft. The child watched from the doorway, entranced, her hands clutching the bear so tight her knuckles went pale. Caleb lifted her carefully, letting her feel the mare’s warm breath, the foal’s tentative curiosity. When the baby horse bumped her fingers with its nose, the child whispered, barely audible, “Soft.” Caleb swallowed hard. “Yeah,” he murmured. “Soft.” And when he asked what the foal should be named, the child considered it with grave seriousness and said, “Dandelion,” like she’d planted a bright thing in the middle of her own darkness.

She didn’t speak much that first week, but she watched everything. Loneliness, she understood better than most adults. The first time she asked Caleb, “You live alone?” it landed like a stone dropped into still water. He answered honestly, because lies were the currency of people who hurt. “Mostly,” he admitted. “But it doesn’t have to stay that way.” The child thought about that for a long time, then whispered, “Me too,” and Caleb felt something crack inside him, not pain exactly, but a door he’d nailed shut beginning to give.

Town gossip arrived like a weather front. When Caleb took the child into Red Hollow for shoes and dresses that fit, people stared as if he’d brought a wolf on a leash. A widow in black lace, Dorothea Grimes, blocked the doorway of the millinery with a smile that never touched her eyes. “Mr. Mercer,” she said, dripping concern like syrup. “And this must be the poor creature you acquired.” The word acquired made Caleb’s jaw lock. “She has a name,” he said. “And she’s not for your inspection.” Dorothea’s gaze slid over the child with a hungry calculation, and the child’s hand tightened around Caleb’s, her face draining of color.

Later, in the wagon, she whispered, “She looked at me like the lady at the orphan place.” Caleb’s blood ran cold. “What lady?” he asked gently. The child’s eyes went distant, shutting down the way a door shuts in a storm. Caleb didn’t push. He simply drove home with his mind racing and a new understanding settling into his bones: this wasn’t only cruelty. It was a system.

That night, Caleb sat with Edith and Hank at the kitchen table while the child slept with the lamp on. Hank spoke carefully, like he was handling dynamite. “Dorothea’s been taking ‘wards’ for years,” he said. “Kids nobody else wants. Calls it charity. Works ‘em like hired hands without pay.” Edith’s face hardened. “And when they’re old enough to leave?” Hank didn’t finish the sentence, because the silence did it for him. Caleb stared at the wood grain on the table, imagining how many children had vanished into that silence while everyone in town enjoyed their supper. “And the orphanage?” Caleb asked. Edith’s eyes narrowed. “Reverend Alden Crowe,” she said. “He runs it here, feeds into the bigger one down in Cheyenne. Folks say he and Dorothea have an arrangement.”

The next morning, the arrangement struck back. A deputy arrived with an envelope sealed in red wax, sweating through his uniform like he wanted to apologize for existing. Caleb broke the seal and felt the world tilt. A summons. Reverend Crowe was challenging the adoption, claiming Caleb had obtained custody through improper channels, demanding the child be returned pending review. Caleb’s first instinct was violence, but Edith caught his arm like a clamp. “Not in front of her,” she warned. “She’ll smell fear like smoke.” Caleb swallowed it down, walked into the kitchen, forced his face into calm, and crouched beside the child as she nibbled a cookie. Her eyes searched his immediately. “Someone going to take me away?” she asked, small voice steady with terror.

Caleb should have told her the truth: that grown-ups were about to gamble with her life like it was a hand of cards. Instead, he looked into those eyes and couldn’t bear to plant another fear. “No,” he said softly. “Nobody’s taking you anywhere.” “Promise?” she pressed. Caleb didn’t hesitate, even though something in him warned that promises were dangerous when the world was crooked. “Promise,” he said. The child nodded and returned to her cookie, and Caleb stood up feeling the weight of his own words settle onto his shoulders like a saddle made of stone.

Caleb hired a lawyer that day, a young man named Eli Parker who hadn’t yet learned how to bow to the town’s corruption. Eli arrived with wire-rim glasses, earnest eyes, and a stack of notes that smelled like sleepless nights. “Crowe’s been running crooked for years,” Eli said, voice tight with controlled anger. “Nobody’s challenged him because he’s got friends in all the wrong places. If we delay the hearing and gather proof, we can protect her and expose him.” Proof became their religion. Dr. Maeve Keating, a physician with steady hands and a spine of iron, agreed to document the child’s injuries so the court couldn’t pretend not to see. The child panicked at the idea, and Caleb spent twenty minutes in the hayloft speaking softly until she could breathe again.

“They look at the bad parts,” she whispered, face buried in her bear. “Like it means I’m dirty.” Caleb’s heart broke in a clean, sharp way. “There are no bad parts,” he told her. “There are hurt parts, and hurt parts can heal. Nothing about you is dirty.” She stared at him, weighing the words. “Will it help fight the bad man?” she asked finally, chin lifting with stubborn courage. Caleb nodded, throat tight. “It might.” She stood, brushed hay from her dress like a soldier readying for battle, and said, “Okay. But you stay.” “I’ll stay,” Caleb promised, and this promise he could control.

Two days before the hearing, a young woman arrived at the ranch with haunted eyes and shaking hands. “My name’s June,” she said, voice barely holding itself together. “I grew up under Reverend Crowe.” Her testimony spilled out like water from a cracked cup: beatings, starvation, children “placed” into homes that weren’t homes at all, Dorothea’s money changing hands with the ease of a prayer. June didn’t describe every horror, but she didn’t need to. The shape of it was enough, and it made the kitchen feel smaller, as if evil took up space just by being named. Eli worked through the night, stitching June’s story to records he’d uncovered: payments that didn’t match any legal adoption, missing signatures, ledgers that proved children were being traded like cattle.

The courthouse on hearing day was packed, half the town eager for spectacle, the other half eager for a verdict that would let them sleep without guilt. Reverend Crowe stood near the front in black cloth, face calm with practiced holiness. Dorothea Grimes sat beside him, gloved hands folded, eyes sharp as pins. Caleb walked in with the child and felt her grip tighten around his fingers. Edith sat on the other side of her, steady as a lighthouse. The judge, Abraham Harlan, looked tired in the way honest men look when they’ve been surrounded by liars for too long.

Crowe’s lawyer painted Caleb as a lonely bachelor playing at fatherhood, a rich man indulging a whim. He spoke of “proper homes” and “appropriate influences,” as if love required paperwork from the church. Then Eli stood and placed Dr. Keating’s report into the judge’s hands. The courtroom shifted, air changing as the judge read the list of documented injuries that could not be explained by childhood clumsiness. Crowe claimed the child had arrived “already damaged,” and the word hung in the room like poison. June rose from the back, trembling, and said, “That’s a lie.” Her voice grew stronger as she named the pattern: children disappearing, Dorothea’s “wards,” the money trail that connected the orphanage to private households hungry for free labor.

The judge’s face hardened into something like weather. “Sheriff,” he said, voice cutting through the noise, “Reverend Crowe and Mrs. Grimes will remain here. You will ensure they do not leave.” Panic flickered across Dorothea’s face, and for the first time Crowe’s calm cracked at the edges. The custody matter still had to be decided, and the judge turned to Caleb. “Why did you take her?” he asked. Caleb looked down at the child, at the bear clutched to her chest like a heartbeat. “Because she was standing on that platform and nobody wanted her,” he said, voice rough with truth. “And because I know what it is to lose everything and still be expected to stand. I didn’t take her like property. I chose her like family.”

The child slipped free of Edith’s hand and walked into the aisle, small feet steady in new shoes. The courtroom held its breath as she looked up at the judge and then, with fierce clarity, at Reverend Crowe. “He says I need a proper family,” she said, voice quiet but sharp. “But I was in his place, and they still hurt me.” She turned back to the judge. “Papa Caleb never hurts me. He stays when I have bad dreams. He lets me name the baby horses. He chose me when nobody else would, and I choose him back.” Silence fell so complete it felt like the building itself was listening.

The judge’s eyes shone with something dangerously close to emotion. “It is the ruling of this court,” he said, voice thick, “that the child remains in the custody of Caleb Mercer, effective immediately. Further, I order a full investigation into the Red Hollow Orphan Home and the activities of Reverend Alden Crowe and Dorothea Grimes.” The gavel came down like thunder. Chaos erupted. Crowe surged toward the door and was stopped. Dorothea’s face collapsed into disbelief. Caleb dropped to his knees and gathered the child into his arms, feeling her tremble turn into laughter that sounded like a bell discovering its purpose.

For a few weeks, the world tried to become normal again. Children were found in Dorothea’s house, thin and wary, learning their names all over. The town’s shame bubbled up as apologies, awkward and late, but real enough to matter. Then, one morning, Eli rode hard onto the ranch with his face gone pale. “Crowe escaped custody last night,” he said, breathless. “We don’t know where he is, but there’s talk he’s coming for revenge.” Caleb’s blood turned to ice, and the child’s hand found his as if pulled by instinct. “Okay,” she whispered before he even spoke. “I’ll be brave.” Caleb swallowed the ache in his throat and began packing, because bravery wasn’t a feeling. It was a series of choices made while your hands shook.

They didn’t make it far. Shots cracked from the scrub brush near the road, a horse screamed, and the wagon lurched as the world exploded into dust and panic. Caleb threw himself over the child, shielding her with his body, hearing Crowe’s ragged voice in the chaos. “You thought you could ruin me!” Crowe yelled, eyes wild, gun raised. Caleb stood, placing himself between Crowe and the child without thinking, because some instincts live deeper than reason. The fight was fast and ugly, more survival than heroism, and Caleb felt a burning sting at his shoulder as a bullet grazed him. Hank and the ranch hands returned fire, and when the dust settled, Crowe lay disarmed and bleeding pride more than blood, his revenge collapsed into the dirt.

Afterward, the child clung to Caleb like a storm had taught her the sky could fall again. She slept beside his bed for days, bear in one hand and the hem of his shirt in the other, as if fabric could anchor the world. Caleb didn’t rush her out of the fear. He let her have it, the way you let an animal tremble after a trap, because pretending you’re fine doesn’t make the trap disappear. One night, when she finally looked up at him with wet lashes, she whispered, “You promised nobody could take me, but he came back.” Caleb swallowed hard and didn’t hide from the truth. “I was wrong,” he said softly. “I can’t control every bad man in the world. But I can promise you this: I will always fight for you. I will always come back. And I will never stop loving you.” She listened like she was building a new kind of belief, brick by brick.

Winter came with its quiet lessons. The investigation turned into reforms. The orphan home was shut down. Eli helped draft laws that made “placement fairs” illegal, and Dr. Keating created records so children couldn’t vanish into paperwork anymore. One spring evening, she came to Caleb with a file and a tired smile. “There’s a boy,” she said. “Micah. Seven. Angry, scared, returned twice. Nobody wants him because he’s difficult.” Caleb looked toward the barn, where the little girl who’d once been silent now laughed as she chased Dandelion through the corral. “I’d need to talk to her,” he said. Dr. Keating nodded, understanding.

Caleb found her brushing the foal with careful hands. When he asked how she’d feel about a brother, she went still, then thoughtful. “Does he have nightmares?” she asked, serious as a judge. “Probably,” Caleb admitted. She considered that, then said, “I had nightmares, and they got smaller when you stayed. Maybe his can get smaller too.” She looked up at Caleb, eyes steady, no longer haunted, only deep. “You have lots of love, Papa. Love doesn’t run out. It grows bigger.” Caleb laughed softly, because it sounded like something Edith would say, but it sounded truer coming from a child who’d had every reason to doubt it. “All right,” he whispered. “We’ll meet him.”

On the porch later that night, fireflies rose from the grass like tiny lanterns learning to float. The little girl leaned against Caleb’s chest, bear tucked beneath her chin, and the world felt wide in a way that didn’t threaten. “Papa,” she murmured, sleep pulling at her voice. “Yeah, sweetheart.” “Remember when nobody wanted me?” Caleb’s arms tightened. “I remember.” She yawned, the sound soft and safe. “I was wrong,” she said, matter-of-fact, as if correcting a math problem. “I just had to wait for the right one to find me.” Caleb kissed the top of her head and watched the fireflies drift into the dark. “We found each other,” he corrected gently, because it mattered that she knew she wasn’t a thing that happened to him. She was a person who chose him back. And in that choice, both of them became something they’d stopped believing in: a family.

THE END

News

All Doctors Gave Up… Billionaire Declared DEAD—Until Poor Maid’s Toddler Slept On Him Overnight

The private wing of St. Gabriel Medical Center had its own kind of silence, the expensive kind, padded and perfumed…

Mafia Boss Arrived Home Unannounced And Saw The Maid With His Triplets — What He Saw Froze Him

Vincent Moretti didn’t announce his return because men like him never did. In his world, surprises kept you breathing. Schedules…

Poor Waitress Shielded An Old Man From Gunmen – Next Day, Mafia Boss Sends 4 Guards To Her Cafe

The gun hovered so close to her chest that she could see the tiny scratch on the barrel, the place…

Her Therapist Calls The Mafia Boss — She Didn’t Trip Someone Smashed Her Ankle

Clara Wynn pressed her palm to the corridor’s paneled wall, not because she needed the support, but because she needed…

Unaware Her Father Was A Secret Trillionaire Who Bought His Company, Husband Signs Divorce Papers On

The divorce papers landed on the blanket like an insult dressed in linen. Not tossed, not dropped, not even hurried,…

She Got in the Wrong Car on Christmas Eve, Mafia Boss Locked the Doors and said ‘You’re Not Leaving”

Emma Hart got into the wrong car at 11:47 p.m. on Christmas Eve with a dead phone, a discount dress,…

End of content

No more pages to load